This is the second entry in a three-piece series on gun collecting from The National Firearms Museum.

Make and model. Condition. Rarity. History. Art.

These are the five factors that tend to appeal to collectors and help determine the value of collectible guns. Tastes differ as to which is most important.

Make and model tends to be the starting point for evaluating collectible guns for most collectors, and will be a basic threshold requirement for those with specialized collections. Factors here include the quality of a particular manufacturer’s products, the historical usage of the guns in question, and the brand’s aura of romance.

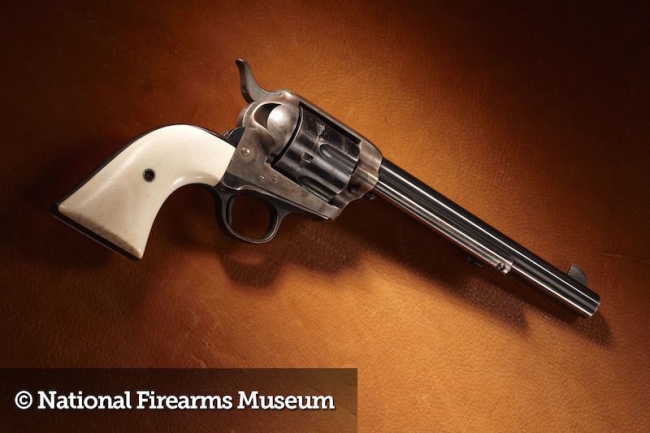

As an example of that last—and most intangible—factor, consider that Colt Single Action Army revolvers were for several decades the most prevalent focus for collectors interested in full-size revolvers from the post-Civil War to turn of the 20th century era.

There is no question that Colts were widely used during that time. Less widely recognized is the fact that Smith & Wesson produced significantly more large-frame revolvers than Colt between 1870 and 1900, and that the S&W top-break pattern was more sophisticated and widely copied than the Colt solid-frame during that era, probably making the Smith-pattern revolvers the predominant handguns of that time.

There are also some who contend that the unusual (by today’s standards) twist-open Merwin Hulbert revolvers manufactured in the Hopkins & Allen plant were the best-made large revolvers of the era, and they certainly enjoyed a level of popularity during that period of use.

It is the Colt Single Action Army, however, that has captured America’s collective subconscious as the quintessential Old West revolver, no doubt aided by decades of Hollywood and television usage, and which became the favorite of many old six-gun collectors.

In recent years there has been a refreshing trend in gun collecting to look at a broader range of guns than the traditional blue chip Colts, Winchesters, and Lugers. The cowboy gun collectors have embraced the Smith & Wessons and Merwin Hulberts, and Colt collectors are looking more frequently at cartridge conversions as significant early cartridge revolvers in addition to Single Action Armies, or turning to the early double-action Colts of the same vintage as the Peacemakers.

P-38s and other auto-pistols have acquired status once reserved for Lugers and 1911s. Military-rifle collectors who once may have ignored anything other than U.S. rifles or Mausers are now pursing British Enfields, Japanese Arisakas, Russian Mosin Nagants, SKSs, and many others.

Obviously, condition plays a major role in the value of a collectible firearm. The classic advice to new collectors in this regard has always been to hold out for guns in the best condition and pay the extra premium they demand. This condition emphasis seems to have developed in the 1970s and 1980s. In the early post-WWII years of gun collecting, there was more interest in rare variations and history and fewer collectors to whom a few percentage points difference in remaining original finish was of much concern.

Although the highest-condition guns continue to bring record prices, it seems that the pendulum is beginning to swing back the other way—a trend met with my hearty approval. The appeal of “mint” guns has been largely lost on me, and seems to be more appropriate to coin or stamp collecting than a field in which the possible historic usage of the artifact holds so much interest and significance. There is a definite segment of the collector market that is not overly concerned with perfect condition, so long as the gun is original and has not been messed with in a more recent (and, in my opinion, usually misguided) attempt to enhance its desirability.

This raises the topic of restoration and refinish, and it seems as if collector opinion is changing here, too.

With prices for high-condition original finish guns running away from the budgets of many collectors, period-of-use refinished guns and older factory-refinished guns are finding more enthusiastic buyers than they did a few years ago.

The availability of excellent-quality restoration services is another factor that I anticipate may impact collector preferences in the future. The top restoration artists are reworking guns to “as new” condition with such skill that it has become increasingly difficult for even knowledgeable collectors to distinguish mint original-finish guns from the best restorations.

When such restoration is disclosed to a prospective buyer (as it ethically should be), the prices the gun will bring are significantly below a similar gun with original finish, and may be less than the original cost of the pre-restoration gun plus the cost of the rework. This creates a mighty incentive for deception by a motivated seller, either by active misrepresentation (aka “fraud”) or passively by simple failure to mention the modification (aka “being a weenie-weasel”).

For some time I have expected the availability of such expert restoration to shake the market for mint collector guns by introducing an element of uncertainty as to the originality of the condition. It doesn’t seem to have much impacted the market yet, but I still suspect that it will.

Before leaving this topic, I should touch on the emergence in recent years of a flourishing “make them match” cottage industry of cannibalizing U.S. military arms of the 20th century to rebuild guns resembling the configuration in which they were originally produced. This practice seems to have gained some acceptability among military collectors. I tend to look at it a bit askance, as it so closely resembles the era when Colt Single Action Army Artillery Models were being butchered to try to remake them into original Cavalry Model configuration revolvers—with a lot of history destroyed in the process. I’m a strong proponent of leaving a gun as you find it and appreciating it for its own history rather than trying to create a facsimile of something it will never legitimately be again.

If make, model, and condition considerations are perhaps waning or broadening a bit, there seems to be some renewal in the interest in guns for factors such as rarity, history, and art.

In terms of rarity, the well-worn saying that “just because a gun is rare doesn’t mean it’s valuable” remains true to a certain extent. There may only be five known examples of a particular gun, but if only three people care about it, the market is saturated.

However, there does seem to be more interest in cornering the rare variations within established collecting fields. There is a bit of a resurgence of the collecting philosophy of completing a punch list of models and variations within a specialization, and this leads to vigorous competition for the rarest examples in these fields. In emerging collecting fields, when new research is published revealing the rarity of certain variations, there can develop a brisk interest in those guns.

Individual guns with a known history of ownership by a specific individual or usage in a specific historical event have always captured the fascination of collectors, as well as historians and the general public. This seems to reflect a basic human interest and shows no sign of abatement. A positive trend here seems to be an increase in general understanding of the type of documentation which must accompany a historically attributed firearm to give it the credibility to justify a premium price, and the importance of creating and preserving such documentation.

While discussing engraving, it’s worth commenting on the market in custom firearms. Generally, highly customized or modified guns will not have their values enhanced by the amount spent on the custom work, and may actually have their resale values lessened by any alterations. There is a specialized collecting niche for the work of some of the famous gunsmiths of the late 19th to mid-20th centuries, such as Neidner & Pope.

Also, in specialized competition fields, common modifications may have value if the gun is resold to a fellow competitor. Otherwise, customization costs should be recognized as expenditures to enhance one’s personal enjoyment of or effectiveness with a favorite firearm rather than as an investment in its value.

Note: Copyright, Jim Supica, director of The National Firearms Museum – used by permission. Opinions are those of the author and not necessarily those of NRA or the National Firearms Museum. Originally published in Standard Catalog of Firearms.

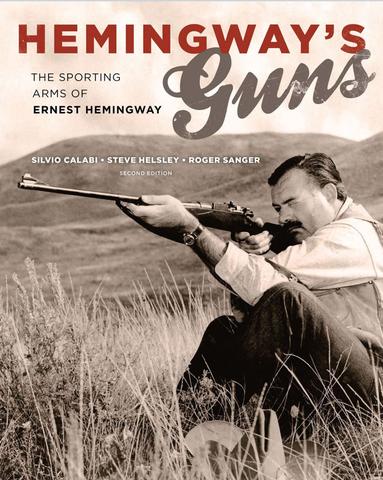

Ernest Hemingway’s friend A.E. Hotchner once described a “yellowed four-by-five picture of Ernest,” shown him by Hemingway, “aged five or six, holding a small rifle. Written on the back in his mother’s hand was the notation, ‘Ernest was taught to shoot by Pa when 2½ and when 4 could handle a pistol.’”

Ernest Hemingway’s friend A.E. Hotchner once described a “yellowed four-by-five picture of Ernest,” shown him by Hemingway, “aged five or six, holding a small rifle. Written on the back in his mother’s hand was the notation, ‘Ernest was taught to shoot by Pa when 2½ and when 4 could handle a pistol.’”

Firearms and shooting infused Hemingway’s existence and thus his writing. He was a member of his high-school gun club and went to war when he was eighteen. He hunted elk, deer, and bear in the American west and went on two extended African safaris, which figured hugely in his writing and changed his life. To the day of his death, Hemingway remained an avid hunter, first-class wingshot, and capable rifleman.

Following years of research from Sun Valley to Key West and from Nairobi, Kenya to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, this volume significantly expands what we know about Hemingway’s shotguns, rifles, and pistols—the tools of the trade that proved themselves in his hunting, target shooting, and in his writing. Weapons are some of our most culturally and emotionally potent artifacts. The choice of gun can be as personal as the car one drives or the person one marries; another expression of status, education, experience, skill, and personal style. Including short excerpts from Hemingway’s works, these stories of his guns and rifles tell us much about him as a lifelong expert hunter and shooter and as a man. Buy Now