The situation in Iceleand reminded me of an existentialist stage play, like Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. Being lost in the fog, with its sensory and sound-deadening effects…was akin to having wandered into the off-stage of life.

Iceland it turns out, is mostly desert. That’s a weird concept to get your head around, especially for such a beautiful country, but it’s true.

When the first Viking settlers landed their open boats on the North Atlantic island in the 9th century, they found a bathtub ring of green, low-canopied forest scrub only a few miles thick, surrounding a volatile central highland — an elemental place largely consisting of ice stacked on top of fire, mostly unsuited even for sheep farming. Those settlers — more farmers than warriors, in truth — cut down the forest (thus knocking over the first domino in a millennia of deforestation and erosion) and quickly claimed all the arable land for themselves. These original farms all remain well-known emplacements today: each named, bounded by low sheep fences or stony Viking cairns, and generally passed father-to-son or father to-daughter for the past 1,200 years.

One of those original families settled at a place called Bót (pronounced “boat”), a large, ranch-sized stretch on the shores of the Ranga River near the modern-day aluminum-smelting town of Egilsstaðir in East Iceland.

Bót is a green and rolling place amidst a mostly stark mountain landscape. Its fields are small and hard-won, crisscrossed with trenches as deep as a man is tall, which provide the drainage necessary to turn peat bog into grassy meadow. Icelandic sheep graze against the walls of the century-old farmhouse in the “homefield,” excluded from the small garden by a fence protecting the tallest tree for miles around. At least one of the early settlers of this place was the ancestor of my friend Snævarr Örn Georgsson.

I first “met” Snævarr via email, having reached out to him after seeing his pictures of enormous brown trout that he had posted to the Internet. Only 25 and an engineering student in Reykjavík, Snævarr’s an amateur scientist who after a stint as a volunteer bird-bander, conceived the notion of conducting his own trout tagging survey on his family river.

I first “met” Snævarr via email, having reached out to him after seeing his pictures of enormous brown trout that he had posted to the Internet. Only 25 and an engineering student in Reykjavík, Snævarr’s an amateur scientist who after a stint as a volunteer bird-bander, conceived the notion of conducting his own trout tagging survey on his family river.

The Ranga is a glacial stream, like almost all free-flowing waters in Iceland. It descends from the mountains north of one of Iceland’s only remaining large forests, over the boundaries of Bòt, where it becomes private family property with no fishing leases for seven miles. In spring, which can extend even into June, glacial runoff washes juvenile Arctic char out of the highlands west of the farm and into the lower river, where they fall easy prey to Snævarr’s huge browns.

The story of trout fishing at Bót mirrors, to some extent, Iceland’s peculiar relationship with the brown trout itself. Like most Icelanders, Snævarr’s ancestors were Atlantic salmon anglers by preference, fishing for native browns only as a secondary pastime. As a teen, Snævarr’s grandfather showed him how to fish below a certain large waterfall near the easternmost, most downriver section of Bót’s private water. From this point upriver, his grandfather explained, the trout do not reach.

Like many anglers worldwide, Snævarr’s forefathers had underestimated the brown trout’s ability to get around large waterfalls. With a typical teenager’s disregard of received wisdom, Snævarr one day decided to challenge the story he had been told, and, sure enough, he began to catch brown trout above the supposedly impassable generations — possibly forever — the fish above that waterfall were unmolested. Unsurprisingly, they were large and more than willing to eat flies.

Like many anglers worldwide, Snævarr’s forefathers had underestimated the brown trout’s ability to get around large waterfalls. With a typical teenager’s disregard of received wisdom, Snævarr one day decided to challenge the story he had been told, and, sure enough, he began to catch brown trout above the supposedly impassable generations — possibly forever — the fish above that waterfall were unmolested. Unsurprisingly, they were large and more than willing to eat flies.

My route over the precarious, rail-less, one-lane bridge leading into Bót’s thick, green home field was lengthy, both geographically and metaphorically. Newly married, my wife, Tracy, and I decided to take a honeymoon somewhere she had never been (and with my spouse this is quite a challenge). I expected something southerly, so when her first suggestion was “What about Iceland?” I found myself looking up airfare prices before I had even finished agreeing to the idea.

Once in-country, we circumnavigated the famous Ring Road, the only land-based path around Iceland. Bót’s location on the opposite side of the island from Reykjavík, the capital city, necessitated several days of falls. Thanks to his forefathers’ mistake, for driving. Along the way we paused to hike the 16 miles up and over the flanks of Eyjafjallajökull (“Island Mountain Glacier”), the volcano that erupted in 2010 and grounded most air travel in Europe for the first time since World War II.

In some ways Iceland is too inviting, and if it had not been for our happenstance meeting with a mountain guide, we might have wandered lost in the impenetrable snow-fog on top of that volcano until rescue crews were dispatched. The situation there reminded me of an existentialist stage play, like Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. Being lost in the fog, with its sensory and sound-deadening effects, and with only small groups of fellow travelers (also lost) for company, was akin to having wandered into the off-stage of life, waiting for the action to once again catch up with us so we could say our lines and move onward into the light.

Led almost like children by the friendly guide, it was not until we crossed onto the volcanic caldera itself — still hot enough to burn off the fog — that we seemed to rejoin the slipping time stream of regular humanity once again. Thus I learned that Iceland, itself a place out of time, has strange effects on its guests.

One evening, bounding over the broken turf of Bót’s sheep fields with the midnight sun just scratching the edge of the sky, I asked Snævarr about his name. My questionable online research had suggested the English translation was “snow warrior,” which I found very much in keeping with my overdramatic image of a proper modern Viking. After he finished laughing, Snævarr explained that his name actually means “Snowman, son of George.” Icelanders eschew the family surname, instead employing patronymics, which change from generation to generation. We paused for a moment before crossing a sheep fence, and Snævarr continued. “If I have a son,” he explained, seeming to look into the future as he did, “his last name will be ‘Snævarrsson.’ And if I have a daughter, she will be ‘Snævarrsdottir.’”

“And what about your family . . . the people of this farm?” I asked.

“This is the family of Bót, that family that lives at Bót,” he acknowledged, “but that is as far as it goes.”

I found the concept strangely liberating, as if each generation was awarded an especially clean slate on which to write the story of their lives.

Such surprising linguistic revelations aren’t limited to an unusual naming system. You see, the Icelandic language literally is Old Norse — in fact, modern-day Icelanders can read the Viking sagas with less difficulty than we have reading Shakespeare, whose plays are only half as old. As the language of a conservative, agrarian people, Icelandic reflects the values and rhythms of the terrain itself. It is a land where the major annual milestones have always been fawning season and shearing season, where even day and night move at a slower pace than in the rest of the world.

Some Icelandic sayings are quaint:

“That’ll heal before you’re married,” Snævarr remarked one afternoon after I cut my hand making hotdogs (Iceland’s national guilty pleasure).

“I just got married,” I replied, confused.

“No, it just means you’ll get over it,” he explained, leaving me to reflect on the implications.

Other Icelandic colloquialisms are downright ominous, like their way of saying they will one day have revenge on anyone who crosses them: “I will meet you at a beach.” Despite their somewhat forbiddingly heroic past, today’s Icelanders are an extremely amiable, well-educated people. In our entire time circumnavigating the island, we did not meet a single person who couldn’t speak English. In fact, many of the Icelanders speak accent-less, grammatically perfect English.

Coupled with the financial crisis in 2008, which crashed the value of the Icelandic krona and rendered travel to the island suddenly affordable, Iceland’s friendly and outgoing nature now poses something of a problem. Indeed, parts of the island are in danger of being loved to death. When I remarked upon the number of tour buses and foreign — especially East Asian — tourists at many of Iceland’s most famous waterfalls and glacial lagoons, Snævarr made a very surprising observation.

“You know,” he said, “tourism only became our number one industry [in 2016].”

“You know,” he said, “tourism only became our number one industry [in 2016].”

That is a very scary thought, and one that has big implications for Iceland’s relationship with fish — especially brown trout.

“In a lot of ways, we have been behind the rest of the angling world,” Snævarr commented. “Catch-and-release only became normal here within the last ten years or so. Fly fishing is also a new thing for many Icelanders. My grandfather did not fly fish.”

With the rise of catch-and-release, and fly fishing itself, has come an increased awareness of the absolutely world-class caliber of Icelandic brown trout fishing.

Historically, most anglers who traveled to Iceland came for Atlantic salmon, fishing private beats on the Lax, or Miðfjarðara, or (the South Icelandic) East and West Rangá rivers for big daily rod fees — sometimes thousands of dollars. Brown trout largely took a backseat as a fill-in target; something to do on your off days if you didn’t want to keep spending thousands searching for salmon.

In recent years there has been a recognition that Lake Thingvallavatn, in Iceland’s centrally located Thingvellir National Park, is home to genetically unique “Ice Age” browns, which have a similar bio-history to the outsized Lahontan cutthroat trout of Pyramid Lake, Nevada. Their special attribute is an ability to grow really, really large in the lake’s waters, which are so clean snorkelers in dry suits can be overcome with vertigo looking down to the bottom. While I was in Iceland a fly fisherman casting from shore pulled a 30-pound brown from private thermal springs on the southern end of the lake.

All of this means that angling pressure is definitely on the increase. If Iceland’s already stressed infrastructure (its parking lots choked with tour buses, its multitude of one lane bridges and its swarming hot springs and glacial lagoons) can be seen as an analogy for the coming effects on fishing, it’s clear that modern conservation measures must also come if Iceland is to remain the glittering emerald of a place that it is today.

This is why Snævarr’s trout tagging study is so timely if Iceland is to protect itself from being loved to death. Above all else, his research shows the value of catch-and-release and proper fish handling in a nation where catch-and-kill is arguably still the norm. Since beginning his study in2010, Snævarr has tagged more than 90 different trout. Each fish was measured, weighed carefully in a net bag, tagged, and then released. I fished with Snævarr for a night, a day, and another night. In that time frame, despite heavy, late glacial runoff thanks to a cold spring season, we recaptured three fish longer than 20 inches on the Imperial scale, or, as Snævarr would remind me with scientific precision, “You mean more than 50 centimeters.”

Two of those fish, both mature males, were among the largest Snævarr had ever caught. Their stories, as recorded in Snævarr’s meticulously kept logbook, were remarkable: In 2010, when the trout tagged as #75 was first captured, Snævarr recorded its length at 50 centimeters (20 inches). He caught the same fish again in 2013, holding in the exact same spot in a pool not far above the “impassable” waterfall. By then it had gained 3-centimeters and weighed more than 3-pounds. Two years after that, in the summer of 2015, I caught the same fish, again in the same pool, and it had gained 3-centimeters, now reaching 22 1/2 inches and weighing close to 4-pounds. Having lost its tag, we were able to confirm that it was the same fish by its distinctive spot pattern above the caudal fin, referencing Snævarr’s original picture before re-tagging it and once again releasing it to continue growing.

Snævarr’s second fish, tag #82, was even more interesting. He had caught it twice before, both times in late summer 2014, only eight days apart. At that time the trout was 54-centimeters (roughly 21 inches), but oh-so-fat-and-happy at more than five pounds. It had spent the summer of 2014 sitting in the canyon section of the river below a waterfall that constantly churned with exhausted, delicious Arctic char smelt.

Snævarr’s second fish, tag #82, was even more interesting. He had caught it twice before, both times in late summer 2014, only eight days apart. At that time the trout was 54-centimeters (roughly 21 inches), but oh-so-fat-and-happy at more than five pounds. It had spent the summer of 2014 sitting in the canyon section of the river below a waterfall that constantly churned with exhausted, delicious Arctic char smelt.

On our second evening, in June 2015, Snævarr caught trout #82 again, but this time it told a different story. For one, it was 2 1/2-miles downriver from the canyon where it spent the previous summer. It had grown a 1/2-inch in length, but it had lost an entire pound — 20 percent of its body mass, sacrificed to winter over just nine months’ time. The smelt, you see, only get washed down when the sun is warm enough to melt the mountain glacier. At all other times the trout must fend for themselves. Just how they manage that was obvious from the state of my brown’s dorsal fin, which was missing a perfect, bite-sized section — a remnant of some earlier attack by a larger, cannibalistic brown. The piscivorous browns of the Ranga also have noticeably longer and sharper teeth than those I am used to catching back home in Arkansas, which, as Snævarr puts it, is “a clear sign that evolution is at work.”

Thanks to Snævarr, a record now exists of the growth rate of these fish. Over a ten-year period or longer he expects to be able to extrapolate age data, plot good years and bad, and, in the long run, begin taking a stab at the possible effects of global warming. Although he has resisted any suggestion of seeking scientific publication (reasoning that doing so would take the fun out of the fishing), Snævarr’s data is very, very valuable to those who hope to preserve and protect Iceland’s tremendous brown trout fishery.

This much is obvious: Snævarr loves Bót. He loves its ramshackle fields, broken into ankle-twisting hillocks by Iceland’s never-ending freeze-and-thaw cycle. He loves its bird species, which he can identify by egg, voice or just a glimpse of awing. And he loves its trout, possibly more than anyone has ever loved anything about that particularly well-loved place.

This is also clear: Iceland needs as many Snævarrs as it can get, because careful stewardship of its resources is the only way to preserve them. Iceland would not be the first nation to admire its natural wonders right into oblivion. With a rising awareness of catch-and release, certainly an awareness that tourism is only likely to increase, and a willingness to question and probe received wisdom, the next generation of Icelandic anglers shows every sign of being up for the challenge. And one day, if Snævarr does have a son or a daughter, he will be able to pass along his own kind of received wisdom: “Above this waterfall,” he may say, “there are still trout.”

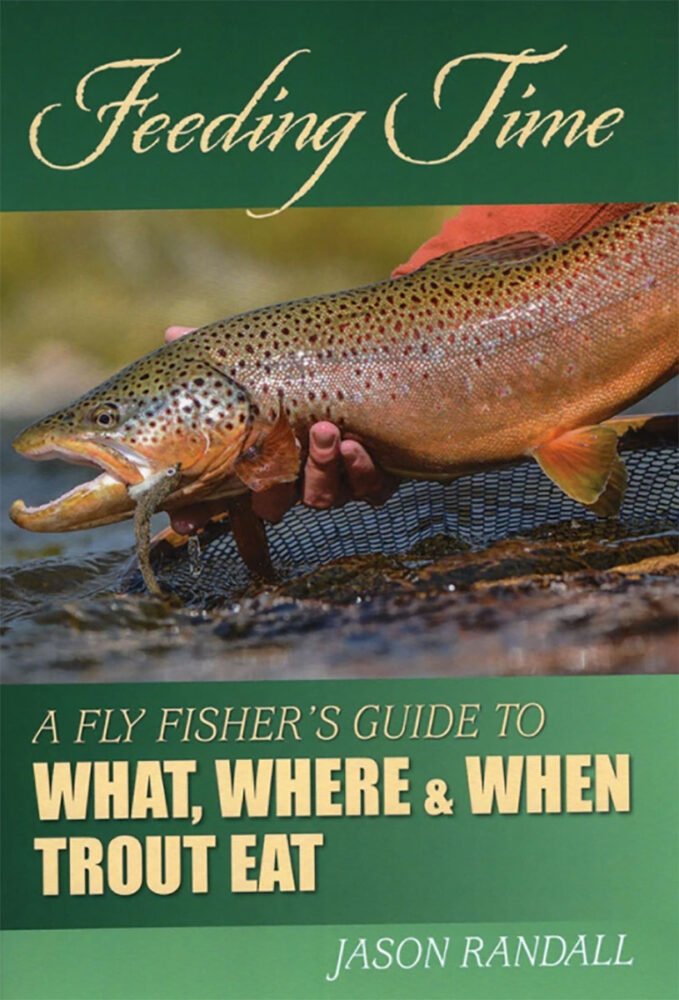

To catch trout, you’ve got to understand their diet and feeding patterns. Author Jason Randall simplifies these complex questions by turning to the science behind animal feeding behavior. You’ll learn about what trout eat, how feeding behavior changes throughout their lives, and where each of the food types is likely to be in the stream environment. The more you understand about the fish and their ecosystem, the better skilled you will be at determining what fish are eating and adapting your fishing strategies to the trout’s routines. Buy Now

To catch trout, you’ve got to understand their diet and feeding patterns. Author Jason Randall simplifies these complex questions by turning to the science behind animal feeding behavior. You’ll learn about what trout eat, how feeding behavior changes throughout their lives, and where each of the food types is likely to be in the stream environment. The more you understand about the fish and their ecosystem, the better skilled you will be at determining what fish are eating and adapting your fishing strategies to the trout’s routines. Buy Now