To get a historic gun firing again is a special joy. To have it fulfill its purpose once again, after a lapse of perhaps a century, makes the joy that much greater.

I was beginning to identify with Ahab, though instead of a white whale, I was seeking a whitetail. Perched 16 feet off the ground in a creaky bow blind as the sun began to set, I asked the hunting gods to pretty please coax a deer to within 30 yards of me before it was too dark to shoot. I needed all the help I could get, as in my hands was a .54 carbine produced in 1864, a Burnside 5th Model. For seven months I had hunted with it unsuccessfully, and I was running out of opportunities for the year. My quest, or obsession as Ken accurately observed, had begun in spring turkey season, had continued through the summer months in pursuit of feral hogs, had slowed but not stopped during bow season, and now into gun season, but increased hunting pressure would soon eliminate 30-yard opportunities. When Hunter offered me the chance to hunt his ranch during the week, I decided I could play hooky just this once.

A deer silently stepped into the food plot and began to browse, then another. The first was a buck with a spike on one side, an obvious cull, the other a yearling doe or button buck. I focused on the spike and hoped he would move into range before light faded, as the coarse sights of the Burnside had proven to be useless to me at last legal light. He did. Here was my opportunity at last. This one was on me.

Were it not for a little dust-up we know as the Civil War, the Burnside would have slid into obscurity. Instead, it became the third most produced carbine of the Civil War.

General Ambrose Burnside was a man of varied and disparate talents and accomplishments—including Civil War Union General, first President of the NRA, sideburns (no, I am not kidding) and gun designer. Though an effective military commander in small unit actions, his record as a Corps commander was mediocre, and his short stint as commander of the Army of the Potomac was a disaster, notwithstanding his magnificent side-whiskers. Following the war, dismayed at the lack of familiarity of Union conscripts with firearms, he served as the founding president of the NRA to promote safe and effective riflery by the civilian population. Lost in the shuffle is the carbine that bears his name.

The Burnside carbine was an attempt to fulfill the promise of the Hall rifle, America’s first military breech-loading long arm, adopted in 1819. Though a capable rifle, the Hall leaked gas where the breach joined the barrel just in front of the firer’s face, affecting power, accuracy and popularity. Burnside’s solution was to design a brass cartridge with a lip—when the action was closed, the lip formed the gas seal and utilizing a loaded cartridge greatly increased the rate of fire. The cartridge did not contain a primer, only a hole, so after loading the cartridge the hammer had to be cocked and a musket cap placed on the nipple. It was cutting edge in 1857, reliable, effective and accurate, and is a true transitional development in arms design. The Burnside became obsolete only three years later when fully self-contained large caliber cartridges, such as those utilized by the Henry and Spencer rifles, were developed. Were it not for a little dust-up we know as the Civil War, the Burnside would have slid into obscurity. Instead, it became the third most produced carbine of the Civil War, and helped the Union calvary eventually overcome the South’s advantage in horsemanship and marksmanship. The Burnside received four improvements in design, the last in 1864. Production ceased in 1865. Its time had passed.

The Burnside design was cutting edge in 1857, reliable, effective and accurate, and is a true transitional development in arms design.

The Burnside came to be mine through a close friend from school. He married into an old west Texas ranching family decades ago and asked my help identifying the inventory of family firearms. After I had done my part, I was asked if I wanted to purchase those that were not family heirlooms. Of course I said yes and the Burnside was included. I assumed it would be just an antique wall hanger, but upon cleaning and a thorough examination it appeared in good working shape. I decided to see if I could get it firing. Time for some research.

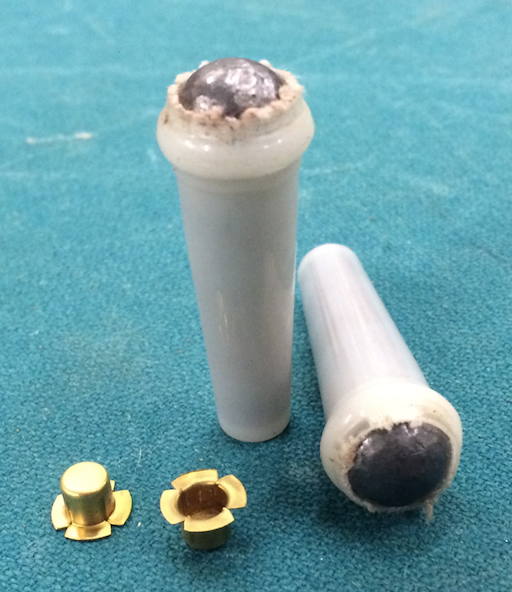

Cartridges are available in both brass and high-density plastic.

Thanks goodness for reenactors. Cartridges are available, both brass and high-density plastic. Loading specifications were readily available. The Burnside fired a .54 conical ball backed by 45 grains of FF powder. The hole in back is smaller than a FF grain, so in theory powder does not leak out. I decided to use a patched round ball and 40 grains of powder, reducing pressure by at least a third, just in case. It worked flawlessly. Now I had to see if I could ethically hunt with it. Though it went bang, both accuracy and power were limited. The sights are coarse and the trigger pull is between 14 and 20 pounds. I decided to limit hunting shots to 30 yards.

I took a spring turkey opening day with a modern firearm, so carried the Burnside the rest of the season. No luck with turkey, so I tried to hunt hogs with it during work weekends at the lease. Tried is the operative term. Three times pigs showed—all were at last light when using a scoped rifle would have been a challenge. I couldn’t find, much less place the front sight, and three, count ’em, three misses were the result. I had success early in bow season so switched back to the Burnside. Naturally, both deer and turkey presented makeable shot opportunities, but it wasn’t gun season yet, and no pigs wandered by. My high hopes for opening weekend of gun season were dashed as no deer or turkey came within range. Hope faded. Then Hunter called with his offer, and I jumped at one more try.

The spike turned broadside at 30 yards, I raised the Burnside and the sights looked crisp and steady as I slowly pulled at the trigger. Then snap, bang followed by a cloud of smoke. The spike jumped then trotted. I did not see blood, and had just enough time to begin to worry that I had missed when he stopped, wobbled and went down after 40 yards. The round ball had exited, and he must have begun to turn between the “snap” and the “bang” based on the wound channel. The ball had passed through both lungs. The Burnside had done its job well one more time, and added another story to its 157 years of existence.

The author was able to shoot this young spike with the Burnside, adding one more story to the gun’s 157 year existence.

I enjoy historic guns, their design, development and use. To get one firing again is a special joy, and to have them fulfill their purpose once again, after a lapse of perhaps a century, makes the joy that much greater. It was worth the time, it was worth the effort, even if one does have to come to understand Ahab in the process.

Michael McIntosh offers practical advice on buying, shooting, and collecting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience. McIntosh also offers advice on buying and shooting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience.

Michael McIntosh offers practical advice on buying, shooting, and collecting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience. McIntosh also offers advice on buying and shooting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience.

As interest in fine double guns reaches a new high in this country, Best Guns serves as both a guide for the uninitiated and a standard reference for the experienced collector and shooter, all written with the precision and seamless grace that were Michael McIntosh’s trademark style.