The harmless character of the game is also changed, for the wild boar is a fierce and dangerous antagonist.

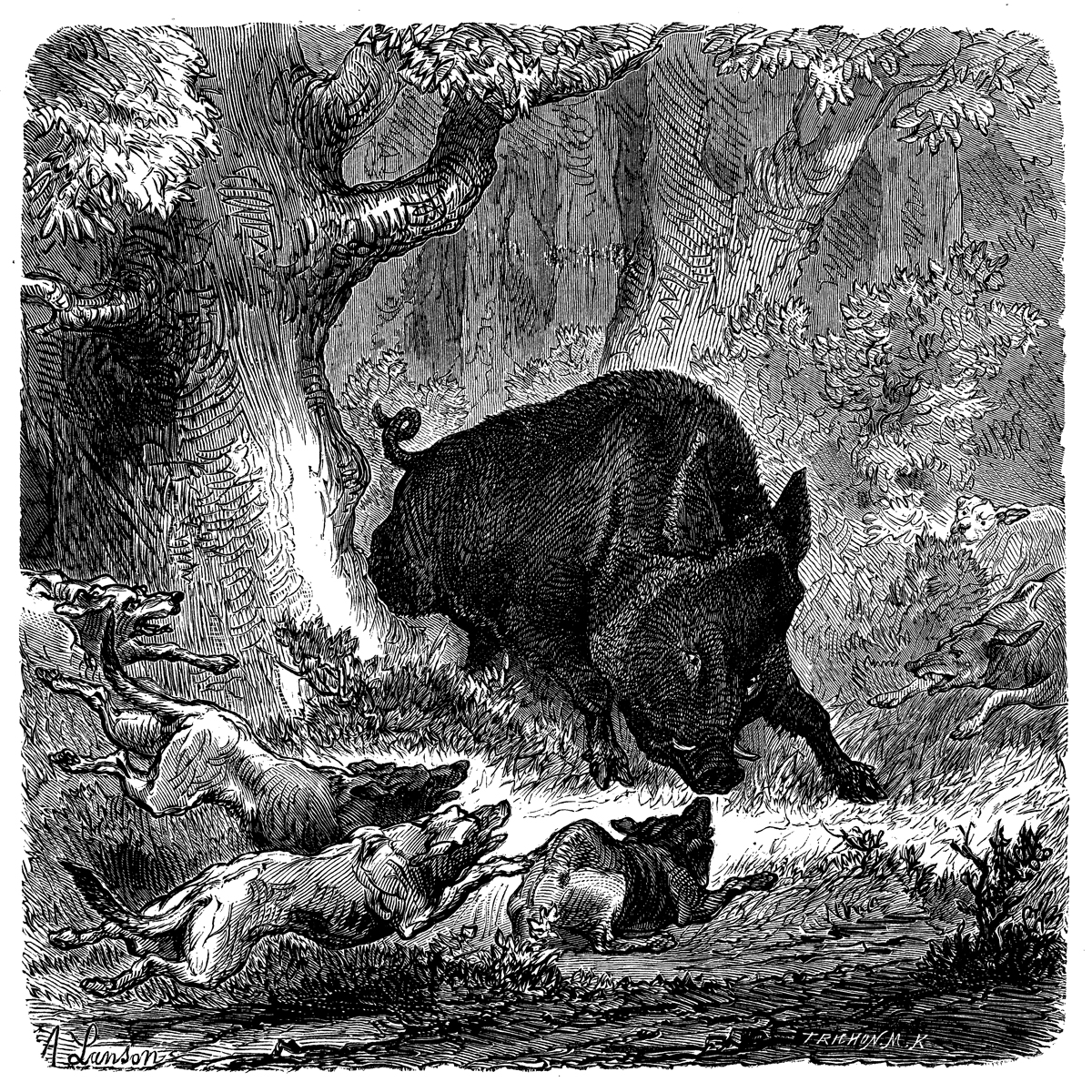

Boar hunting is held by the French and German aristocracy in the same estimation as fox hunting is by the English gentry. But in a boar hunt, the sylvan scene of the shires is changed for one wilder and more picturesque. The old tusker must be sought in his native wilds, among the dense forests that clothe the rugged mountainsides. The harmless character of the game is also changed, for the wild boar is a fierce and dangerous antagonist.

When mature, he roams the woods alone, and no animal cares to dispute his right of way. Gaunt and lank, wiry and active, he travels over a great extent of ground during the summer months, feeding on grasses, berries, and roots, which his great snout, armed with long, gleaming tusks, easily enables him to procure, occasionally making a raid on the cultivated fields at night and playing havoc with the farmers’ crops. In the fall he feasts on beechnuts, chestnuts, and acorns, and becomes tolerably fat.

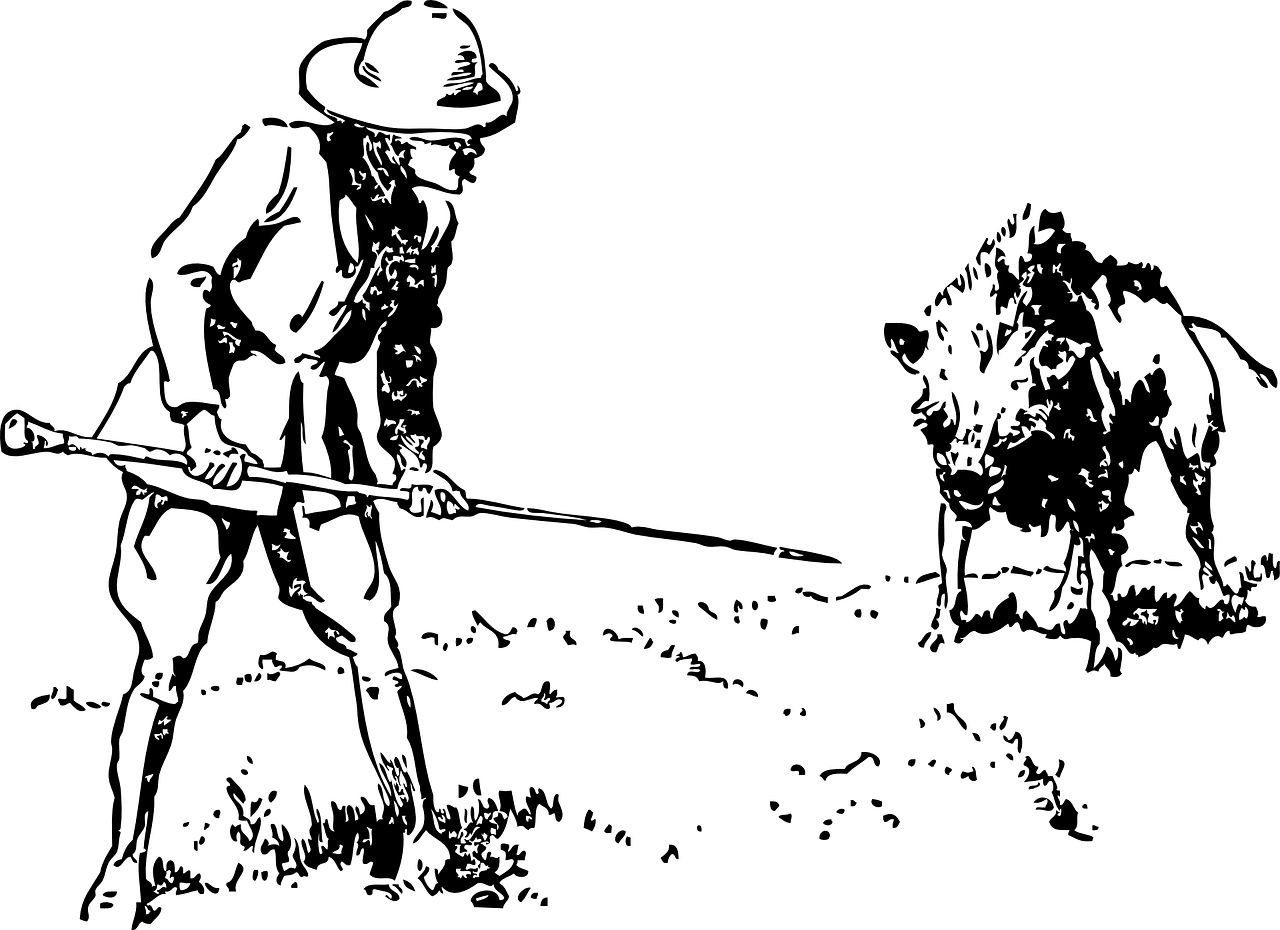

Then the woods resound with the bay of hounds and the clear, shrill notes of the hunter’s bugle. There are two ways of hunting: with spear and knife, or with the rifle. The first method appeals most strongly to the bold and experienced hunter, for to face the boar when brought to bay, to stand before those keen tusks, dripping, perhaps, with the lifeblood of the bolder hounds, and to deal the death stroke with a spear requires great nerve and skill.

Let me attempt to describe such a chase, in which I took part among the wild glens of the Ardennes. We hunters were already stationed in a long line across a thickly wooded valley when the sun rose one fine October day and drove the white mist slowly up the mountainsides. Dewdrops sparkled and glistened on the canopy of leaves, on the brambles and bushes that choked the way, and on the luxuriant growth of weeds and grasses underfoot. The morning air was full of the damp, earthy odor of vegetation, and no sounds were heard, except the occasional notes of birds as they welcomed the break of day.

Each hunter was armed with a muzzleloading rifle and a long, sword-like knife. Should the hunter only wound a boar with his rifle, the probabilities are that the animal will charge. If there is no time to reload, and if one cannot escape by dodging around the trees, he must resort to the knife. Kneeling and holding the hilt against his breast or knee, the hunter receives the shock of the furious charge.

On the day of which I write, the beaters and dogs had been abroad before dawn, and were driving the game toward the valley where we stood. Presently the distant baying of the hounds reached our straining ears, and then frightened little animals came scrambling through the bushes. Foxes whisked in and out of sight with stealthy steps, martens and stoats tripped lightly by, and at a loud, crashing sound I grasped my rifle, only to see the branching antlers of a stag fly by as the graceful creature bounded away.

Then came a fearful rustling and crackling in some blackberry bushes, a grunting and snorting there was no mistaking, and a great boar, covered with long, grayish-brown bristles, all on end, appeared for a moment and then was lost to view among the dense brambles. I was ready for him, but as the hammer of my gun fell, the impotent click of a bad cap lost me the first boar of the day. Crack! went the rifle of the next hunter, and the groan of the mortally wounded boar, and the triumphant tra-la-la of a bugle announced his successful shot.

Other rifles cracked to right and left. The sport became general and the forest resounded with the crashing of the underwood, the reports of the guns, the baying of the hounds, and the ringing sound of the horns.

Twice a great sow charged right by me, but only boars were to be shot. I lowered my gun in disappointment when I failed to see the great tusks that curl over the huge snout of the male.

At last I was rewarded when a great brute came tearing through the bushes not ten yards away. His fiery eyes glared savagely and foam dripped from his champing jaws.

Crack! I sent a bullet through his shoulder and he fell. In his struggles he plowed the ground with his hooves and tusks, but a lucky stab with my knife ended him.

Loading quickly, I was able to get a snapshot at another big boar rushing along about 20 yards to my left. The bullet grazed the skin on his back and, with a shriek of rage, he stopped and faced me. In another second he charged. I threw down my rifle, drew my knife, and kneeling behind the body of the dead boar, I prepared to receive the furious brute. Luckily, a bullet from a neighbor’s rifle smashed his left foreleg and I was spared from experimenting. But the courage of the boar was not subdued by the loss of a leg and he still attempted in vain to reach me.

Another snapshot put a bullet through the heart of a small boar, then the foremost dogs came up and the sport was over for the riflemen; but the spearmen followed to kill those boars the dogs had brought to bay. One old hunter received a painful, but not dangerous, gash on the leg when attempting to spear a boar, and one of the riflemen got his wrist broken in receiving a half-grown boar on his knife.

Our bag that day consisted of 28 full-grown and 11 small boars, and that night we had a right royal feast at the hunting lodge. The head of the largest boar was carried into the dining hall, lying in state on a silver platter and received with all due ceremonies.

Editor’s Note: This article first appeared in Outing magazine in October 1895.

Horned Moons & Savage Santas is a collection of some of the best stories ever written by such re-nowned sporting legends as Ernest Hemingway, Robert Ruark, Gordon MacQuarrie, Howard Walden, Jack O’Connor, Arthur Macdougall, Robert Murphy, and many, many more. With more than fifty superb illustrations, this book is destined to become a classic in its own right. Shop Now

Horned Moons & Savage Santas is a collection of some of the best stories ever written by such re-nowned sporting legends as Ernest Hemingway, Robert Ruark, Gordon MacQuarrie, Howard Walden, Jack O’Connor, Arthur Macdougall, Robert Murphy, and many, many more. With more than fifty superb illustrations, this book is destined to become a classic in its own right. Shop Now