Tony Kinton details the ups and downs, reliefs and frustrations and the total fulfilment of experience that comes with the hunting of old.

Obstinacy is considered poor taste. But fracturing protocol and proper behavior were not my intent. Rather, I was simply curious and had years earlier heard a distant drum, the cadence of which captivated me. So with all the grace I could muster, I approached my colleagues and declared that I would not be similarly attired or equipped as most come hunt time tomorrow. They nodded, bewilderment wrinkling their studious brows. Then, off to bed.

A touch of trepidation followed me to the coffee pot pre-daylight. Others were gathered, their stares abundant but kind. I wore moose-hide center seams, buckskin leggings, long-hunter shirt, canvas weskit, heavy wool capote and floppy felt hat. A .54-caliber York-style flintlock was tucked under my arm. Left-hand lock, thank you. A pronounced anomaly I was among those clad in camo and toting scoped rifles and guarding their comments. Within minutes we exited for selected stations in the Delta bottomlands. I was a part of the group, but also very much apart from the group. My route seemed particularly lonely that cold December morning.

Full 18th century garb is the author’s preference. The wardrobe accentuates the hunt.

This journey in which I was engaged is often lonely. Few choose to follow anxious, difficult steps toward success when a given project is plagued by obstacles at the outset, obstacles that are marked by the absence of modernity. Those reticent to join tend to be practitioners of technology, perhaps have erroneously accepted the suggestion that new is essential. And if success were judged only by game taken, there is validity in that errant acceptance. But they, the ones absorbed in updated contrivances, possibly neglect finer nuances in favor of the latest offerings.

Success, however, is not simply winning the prize, at least when hunting is the selected endeavor. Success, true success, is far more complex. It is something that claws its way to the core of one’s being and is determined by that one and that one only. “Success” in this usage of the word is an essence, a particular challenge, a wondering. Esoteric perhaps. Moving backward in choices of tools and clothing and methods affords such elements as those just mentioned and adds a peculiar spice to an unfolding journey, flavoring the spirit even when that journey is lonely.

Management on the property we were hunting required a doe before a buck. That first came quite handily. I was perched in a treestand, a slightly distasteful regimen for what I attempted to replicate. Still, it is reasonable to conclude that those who came before me surely, on occasion, took shelter in a toppled tree or tangled cane in hopes of intercepting game. That considered, I found the treestand more palatable.

Five deer came along. Two were bucks with promising but youthful antlers that failed to meet parameters of the management scheme. The other three were does – fat and graceful and shimmering in an early morning sun. Flint clacked against frizzen, a whoosh erupted from the pan and a thudding, blackpowder rumble disrupted giant, quiet woods. I eased from the stand, knelt beside the doe and offered a prayer of thanks. Presently, I removed the wool capote. It would not be needed again that morning.

The author’s favorite turkey tool: a 20-gauge fowling piece and requisite accessories.

After some silent reverence, I opted to employ the tactics of 18th century longhunters, or the tactics I envisioned them using anyway. Soft moccasins making nary a sound on damp-leafed sod. Supple leggings brushing away briars and stubble. Weskits and bulbous-sleeved, thigh-length hunting shirts muted an autumn brown in dye brewed from walnut hulls. And, of course, the flintlock rifle, shooting pouch and powder horn dangling from one shoulder. That was my mental picture of those early ones; I mimicked them as accurately as I could. And, as I was slipping from tree trunk to tangle to head-high cypress stump seeking and blending into shadows where they fell, I saw the buck.

Sleek, well antlered though no giant, muscular body that spoke of four or more years — he came drifting along in the big oaks, occupied by the occasional acorn. But his primary interest fell on one specific doe, one of four in the entourage. Breeding was still only hoped for, but the promise would materialize in a few days. When the doe moved, the buck moved. At 60 yards he struck a pose; the doe nibbled on acorns in a dry slough. A mystical piece of wildness he was. And the flintlock belched blue-gray smoke in a putrid cloud.

Two hours earlier I had sat beside a doe, one still lying back a way near that metal stand. Now I repeated the ritual – kneeling, praying in thanksgiving, stroking the coat and admiring the antlers of a fine buck, sad in a joyous and fulfilling way that is impossible to explain save to those who have experienced it. I went back to camp to gain assistance, a modern longhunter in a modern world, a hunter who yet dreamed of the what and the how of the past. All at camp agreed to help, but none showed inclination to do things the old way. Still, each nodded affirmation.

Kinton likes a handmade cedar box with separate striker for his longhunter replications. Though the diaphragm and other more modern calling devices are grand, the cedar friction call seems to fit the setting of a long hunter.

And then Texas. Turkeys were the premier goal, and for that I left the .54-caliber behind and took a 20-gauge fowling piece. That unit began life as a roughed-out block of walnut, a Colerain barrel and an L&R lock. I acquired these ingredients–lock, stock and barrel–and shipped them to Clay Smith in Williamsburg, VA. He did the tough work: inletting the barrel, lock, trigger guard and butt plate. I did the simple chores of browning the barrel and finishing the wood. This was a basic unit–no frills. Pedestrian. Utilitarian. A fine reproduction of the workingman’s fowling piece brought to the colonies from England. It turned out as I wanted.

And for one ill acquainted with traditional blackpowder firearms, it is germane to announce that all such devices have their peculiar set of idiosyncrasies. Get them right, and these tools perform in fine fashion. Get them wrong, and life can be dismal. Fowling pieces, at least in my 40 years of tinkering, seem especially well endowed with contrariness. They tend to favor one, maybe two combos of ingredients stuffed down their bores, and all other offerings of powder, wad and shot follow a path of progressive declination.

I spent hours of pleasurable and sometimes frustrating powder burning. The Colerain barrel, however, built with a specialized choke system, was quite agreeable, shooting efficacious patterns with various arrangements of components. I eventually settled on 75 grains of Goex FFg blackpowder, three thin cardboard wads, one felt wad, 100 grains bulk measured of No. 6 magnum shot and one over-shot thin cardboard. I primed with a dusting of that same manufacturer’s FFFFg. So loaded, my fowling piece was a sure thing for any reasonably-distanced gobbler or a fat squirrel in a tall hickory for that matter. I have held to this recipe since first recognizing the fowling piece liked it, and the pleasant performance has dissuaded any desire for more experimentation.

Truly primitive camping is an interesting addition to blackpowder hunting. The author, however, no longer enjoys sleeping on a cold bed of leaves.

In any discussion or contemplation of those commonly known as longhunters, their tools claim a great deal of thought and verbiage. But it is the people themselves—men for the most part, gamboling from settlements to hinterlands–who are likely the most intriguing entities. And I must be reminded, before scoffing at technological advances and their employment in hunting fields today, that the tools of those ramblers were, at the time, the most modern available. Such sober revelation makes polymer-tipped bullets and supreme optics and long-range rifles less obtrusive to my sensibilities, more acceptable to one born three centuries too late. But I digress. Now back to the longhunters.

Men of great skill and resolve they were. Simply, they knew their business. Otherwise, they didn’t survive to bounce grandchildren on aged knees. Men such as Casper Mansker, Daniel Boone and Simon Kenton are legends. And Simon might, should I research, turn out to be kinfolk, though he surely missed the correct spelling of his last name. Contrary to much opinion, none of those men were faster than a speeding bullet nor could they leap tall buildings in a single bound. They were men. Resourceful and adventurous and dedicated to the task before them, but still just men. It was with such recognition and reflection that I took the 20-gauge fowling piece to Texas.

The algerita bush hinted spring. Its yellow flowers danced with brilliance in early-morning sunlight. From a few feet away it was inviting, asking a visitor to stop by and caress the blossoms, smell the fragrance. But those schooled in such matters know better. Handsome blooms are protected by angry leaves with spiked tips that belie the plant’s apparent graciousness. And those leaves from last year, now curled on the ground, preclude sitting nearby.

Casting round balls over the fire of a primitive camp.

It was March–not yet spring in full measure. And it was Hill Country Texas–a land profusely festooned with entities ready to scratch, sting, stick or in some additional way thoroughly annoy even the most harmless innocent who chooses to wander this grandiose but often inhospitable landscape. I embraced that reality, admired the visual pleasantries and moved on.

The year was 1770. Reality, however, supported by a cell phone vibrating from inside the haversack, suggested an error in my thinking and encouraged me to admit the year was actually 2015. But I was too deep in pretense to entertain such nonsense. My reply to said message noted all was well, and I tucked the intrusive device away and began once more to pretend. That fowling piece in my hands gave a boost to this make believe.

Loading the fowling piece can be a protracted regimen. Here the loader places the third of three thin cardboard wads atop the powder charge. These three will be followed by a felt cushion wad beneath the shot.

A March wind was unkind. It not only chilled me but distorted gobbling from three separate locations. How far? How many gobblers? Which area held more promise? This way or that? I untied a canvas greatcoat from atop the haversack and snugged it into place in an effort to thwart an uncomfortable bite riding that wind.

I looked and listened and then moved toward a stand of twisted and dwarfed oaks—an acceptable station from which to call I allowed. And I thought again, that most perplexing question of humanity disturbing my tranquility. Why? But this contemplation didn’t specifically deal with why as it related to life’s complexities. Rather, I wondered, at least at that moment, why I elected to gravitate toward the past rather than become enamored of the now and future. A similar episode of mental gymnastics had emerged during that deer hunt highlighted earlier in this story.

This line of thought has been a frequent visitor over the years. One firm conclusion always arises, and that conclusion is that the experience is paramount. For it is the experience that surfaces as the grandest portion of any venture into wild places. Modern trappings may at times subtract from rather than add to the entire affair. They threaten to erect some existential barrier in the path of proper absorption and morph sentiment, replacing it with acquisition. Or so it seems.

Shot goes down the bore. A thin cardboard wad will top the shot, holding everything in place.

And dreamers of yesteryear can’t overlook curiosity when probing that question of why they sporadically embrace the old. How did those early ones function? Could modern wanderers do the same? If so, what were the criteria for that functioning? Stepping back in time permits that curiosity to find answers. Doing so is an enriching exploration that in and of itself generates a worthwhile endeavor sure to round off the rough edges of haste. Collecting game moves to second place in favor of the method used in that pursuit.

I elected to keep things spartan, to search for essence, the basics of days known only through history and perhaps known through one’s own recreating of that history. Ramblings complete, both in mind and footfall, I sat at the base of an oak. A turkey gobbled. Or was it two, three maybe? Still distant, but the wind could be toying with auditory abilities. Could be they were closer than I perceived?

Fine-grained powder, such as FFFFg, is best for priming the pan.

Over my right shoulder and over the coarse collar of the greatcoat, I saw a sizable collection. Behind me, more were ghosting through mesquite in front and to the right. One gobbler, apart from these two visual verifications, was proclaiming his worth down a two-track to my left and out of sight. That same dim road was 30 yards from me. And all three identifiable groups–or perhaps only one bird on the left–were converging on that little ranch road. I yelped softly on a handmade cedar box with detached striker. Multiple responses.

Turkey hunters well know this rush of anticipation, this flood of hope, this quiet questioning of doubt–almost a dread of potential defeat. Had this setting been faced with modern gear and clothing and calling devices, that latter–defeat–possibly would have been mildly mitigated. But I had chosen otherwise and opted for the more tenuous. Margin for error shrank and within minutes the results of this, some might say frivolity, would become the past.

A broad assortment of hens was first to enter that two-track and crane inquisitive necks searching for some wayward compatriot somewhere there in the oaks. They clucked and scratched and meandered until finally moving along. Following were three big ones—gobblers all. They initially appeared as a giant glob of black and iridescence and barred wings, tails full sail and heads tucked tightly into a pillow of feather fluff as they pirouetted and drummed for attention. An outsized patch of brush afforded only a veiled view of their antics, but they soon passed that brush and became individuals, each equal and each vying for the role of emperor. One, open enough to assure that the shot pattern would encounter only him, slowly folded from strut and his head was clear. I had the fowling piece pointed at the spot.

Through a dense cloud of smoke, I watched as the sky and that ranch road and clustered mesquite trunks filled with that intoxicating sight of wild turkeys, individually and collectively departing with great haste, some running and some flying. All were suddenly gone; except one. He was there. Still. Prostrate. Grand and glorious and glistening in that rugged road. I sat quietly for a spell, absorbing and overflowing with that essence, celebrating that experience, knowing completely the answer to that question of how, and I also knew the answer to why.

Kinton took this Tennessee boar with a .54-caliber York rifle.

Later, I sat beside that fine gobbler as I had many times before and have many times since with flintlocks and a host of wild things, both large and small. Again, that prayer of gratitude. I wore that bird over alternating shoulders as I walked the half mile to my truck, all the while considering how I might answer should I encounter a ranch hand or fellow hunter or game authority who had not been warned of the oddity they might find somewhere in those rocky hills of Texas. Honestly, I had little concern how I would answer. One word should suffice–essence.

That fowling piece, along with the .54-caliber York and a .32-caliber Tennessee, all flintlocks, rest peacefully within reach of this miserably modern and terribly frustrating computer on which I write these words and with which I will transfer them to this publication you now read. They, the flintlocks, are reminders of who and what I am. With regret, I don’t use them now as much as I once did. But then, I don’t do a great many other things as much now as I once did. I more often today find myself behind a 28-gauge Beretta Silver Pigeon or a 20-gauge Browning Citori or a Ruger No. 1 in 9.3x62mm. Maybe one of my nostalgic lever rigs occasionally. Time and age, I suppose.

But, the flintlocks are there; I choose not to part with them. They are comforting. I find tranquility in their nearness. And when I do take them out for whatever reason, I am transformed. Set in a place and time I never knew apart from my own fantasies. And that is quite the reward. The flickering fire and restful recall of experiences. Being lonely is not all bad.

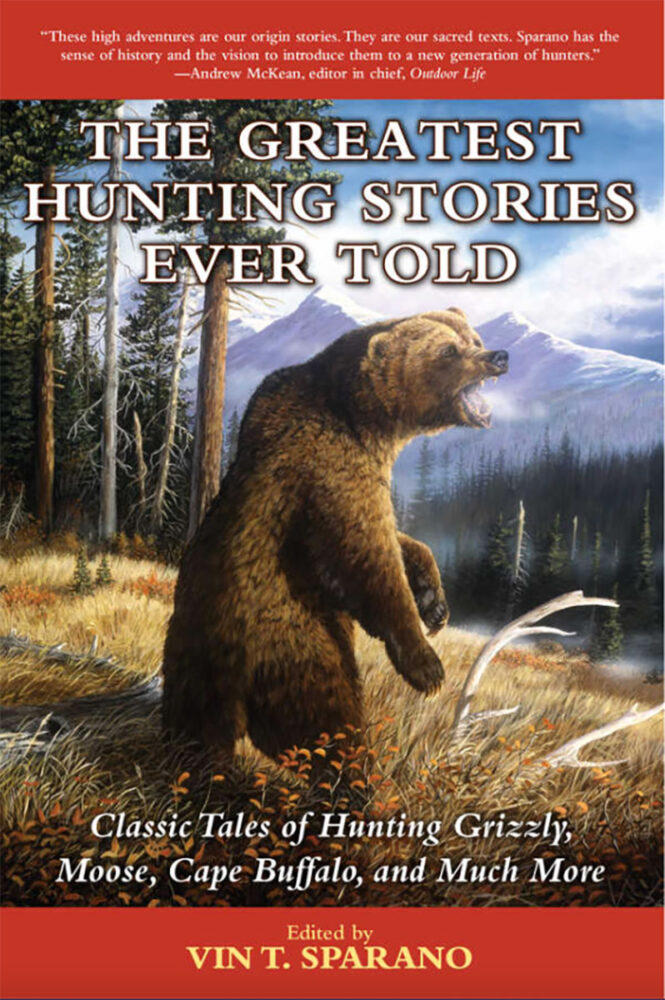

Now, for the forty million Americans who hunt, here is the perfect companion. The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a collection of true hunting tales, told by some of the most courageous and clever sportsmen. The quest for adventure has touched all these writers, who convey the drama, tension, stamina, and sheer thrill of tracking down game. Included here are the experiences of Teddy Roosevelt in “The Wilderness Hunter,” of Jack O’Connor in “The Leopard,” of J. C. Rickhoff in “Wounded Lion in Kenya,” of Frank C. Hibben in “The Last Stand of a Wily Jaguar,” and of John “Pondoro” Taylor in “Buffalo,” among others. Buy Now

Now, for the forty million Americans who hunt, here is the perfect companion. The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a collection of true hunting tales, told by some of the most courageous and clever sportsmen. The quest for adventure has touched all these writers, who convey the drama, tension, stamina, and sheer thrill of tracking down game. Included here are the experiences of Teddy Roosevelt in “The Wilderness Hunter,” of Jack O’Connor in “The Leopard,” of J. C. Rickhoff in “Wounded Lion in Kenya,” of Frank C. Hibben in “The Last Stand of a Wily Jaguar,” and of John “Pondoro” Taylor in “Buffalo,” among others. Buy Now