The hawk circled me, more familiarized than trained that the perch of my arm meant food. It cut between the branches twice before landing—exactly how Ed and I had planned.

Ed Coulson was my hawk-handler for the day, an experienced falconer employed by Ireland’s School of Falconry on the grounds of Ashford Castle in County Mayo. Beckett, my hawk, was a male equipped with a bell for nearby tracking. Ed had also placed a telemetry transmitter on him when we’d first set out, just in case the bird flew too far away. Both devices, I learned, are now common practice in falconry.

I also learned that Beckett was smaller than his female counterparts—all male hawks are—and that he had no sense of smell. When I released his jesses, thin straps of leather used as tethers, from my grip, he perched in a big tree above a smaller one that had equal parts ruby-red leaves on the ground and in its branches. The red tree was stunning in the open field, surrounded by golden leaves.

Beckett hadn’t perched terribly high, being a hawk.

“A falcon would’ve perched higher,” Ed said.

Ireland’s Ashford Castle provides a historic tie to the timeless art of falconry.

Falconry is roughly categorized into three groups: short-winged (hawks), long-winged (falcons), and soaring birds (eagles, red tails). Most commonly practiced with hawks, falconry works through positive reinforcement alone. You feed the bird and provide the perch of your arm. You offer it a warm barn at night. And you help it with its quarry when it’s too big, substituting a ready-made bite for the rabbit you take home for yourself.

Above all, birds of prey want to conserve energy, so they go along with letting you do the dirty work. Skinless beef, day-old chick, and pheasant’s wing would have all been fed to Beckett were we on a hunt. He would have covered his quarry with his wings, but as the work of plucking would have lay before him, he’d have happily swapped.

“The relationship is kind of artificial because of the maintenance,” said Coulson.

Ed Coulson, falconer extraordinaire.

The bird and I were not soul mates; no trade and he would have flown on to another perch without concern of return. But there were things one could count on: Beckett had been conditioned to rely on the comfort of his mew, an enclosure for trained hawks. If he caught a rabbit, he could count on me—in theory—to substitute his work with a ready meal. My job was to be a good waiter—serve a steady supply of food, then disappear.

There was more I could do to lose the bird than keep it, which is how we should all treat our animals and people. But the quick flight of a bird of prey from our arms and his swooping dive back serve as reminders of the relationships inherent to sportsmen.

If it were only about killing, gun technology would have rendered falconry obsolete in the Elizabethan era 400 years ago, as falconry has a success rate of only 20 to 30 percent. But hunting by bird or hunting by gun is not a binary choice, and one can certainly appreciate both.

Hawks, falcons, and eagles can all be trained, but falconry is most often performed by hawks.

Ed was a philosophy major, “but that was ages ago,” he told me. “Nothing to do with biology.” He spoke with his back to me as we walked through the temperate rain forest where moss grew on all sides of the trees, so there was no need to gesture to him that his degree had everything to do with biology.

When we came into a clearing, I asked Coulson about falconry’s tipping point. I’d perceived it as somewhat popular as of late, though I wasn’t sure if its imagery had simply been put before me for enough years that I was simply circling around to it.

I was reluctant to mention Harry Potter and the characters’ pet owls, but once I did, Ed referenced H Is For Hawk, published in 2014. This book was specifically written for adults, and when I walked back to the village of Cong after my falconry session and wandered into a bookshop, there was a copy among the titles about angling, for which Cong is well known.

A falconer and her bird paint a beautiful picture on the background that is Ireland.

I asked Ed if H Is For Hawk was a work of fiction.

“It is nonfiction,” he said.

It was clear in his reply that he loved the book, but he did not say as much. Later, when I read the author’s account of grieving her father by training a difficult goshawk, I came to understand that falconry was cyclical. You don’t train these birds. The relationship you build is one of trade; you give them a reason to circle back to you. It’s very unlike the relationships that develop between humans and their horses or dogs, but just as powerful. All the bird ever has to do is not return.

We think we are living a straightforward narrative, but, like grief, falconry reminds us that very strange things can happen with time. Memories from long ago can circle back like a hawk to your arm. Time can be measured by landings.

I had to remind myself falconry was not specific to the British Isles or Harry Potter. It was the pastime of Middle Easterners; it was steeped in the histories of multiple cultures from prehistoric times, as evidenced in some of man’s earliest writings; and the thing they all had in common was relationships.

In my mind that day, I romantically pictured a man on a horse in a good hat, with a dog running alongside him and a bird of prey returning every so often. The image works, not because the man has trained the bird, but because everyone is feeding each other.

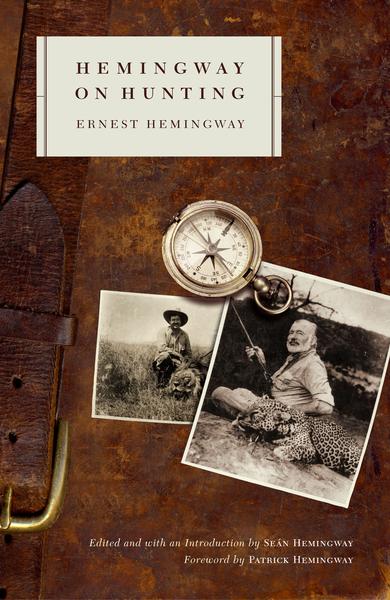

The companion volume to the bestselling Hemingway on Fishing.

The companion volume to the bestselling Hemingway on Fishing.

Ernest Hemingway’s lifelong zeal for the hunting life is reflected in his masterful works of fiction, from his famous account of an African safari in “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” to passages about duck hunting in Across the River and Into the Trees. For Hemingway, hunting was more than just a passion; it was a means through which to explore our humanity and man’s relationship to nature. Courage, awe, respect, precision, patience—these were the virtues that Hemingway honored in the hunter, and his ability to translate these qualities into prose has produced some of the strongest accounts of sportsmanship of all time.

Hemingway on Hunting offers the full range of Hemingway’s writing about the hunting life. With selections from his best-loved novels and stories, along with journalistic pieces from such magazines as Esquire and Vogue, this spectacular collection is a must-have for anyone who has ever tasted the thrill of the hunt—in person or on the page. Buy Now