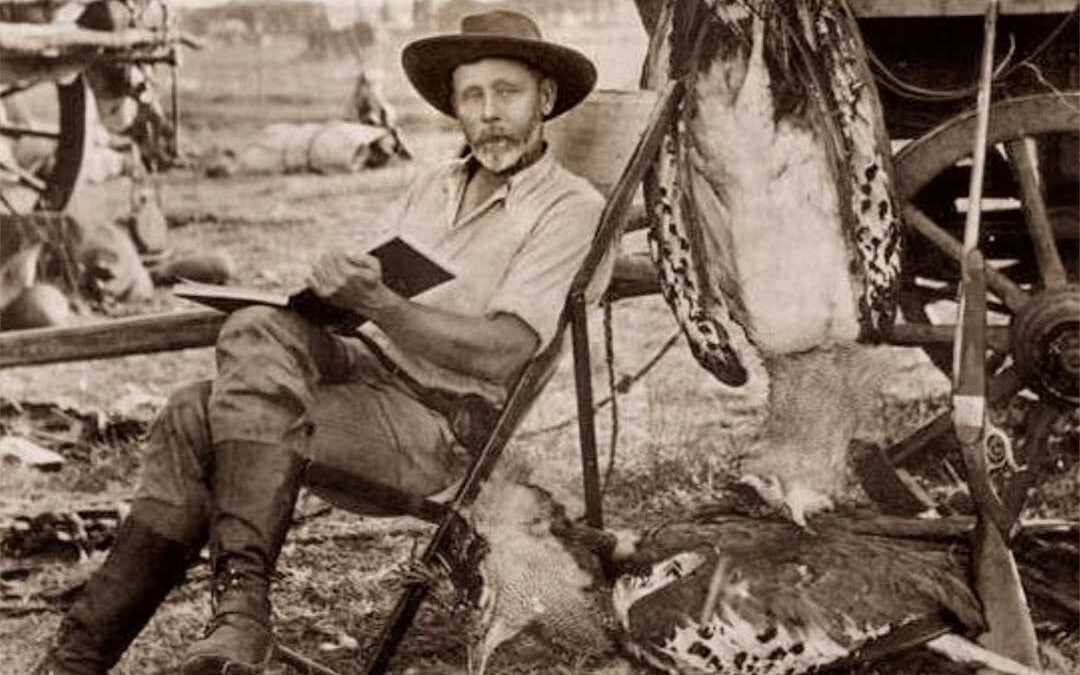

Harry peered into the August night. He’d ridden ahead, his dog trotting beside. Camp staff would follow with pack animals and the rest of the dogs. Ten clicks on lay a water hole. Clumps of bush and tall grass passed slowly as shadows. Suddenly two solid shapes loomed, short yards away. Lions.

Time sped up. Spinning his mount around, Harry spurred it hard. Too late.

The impact almost took him from the saddle. His horse’s reaction to the lion’s claws did. Harry pitched off, nearly landed atop the other cat, rocketing in to throttle the horse. Great canines snatched at him as the first assailant bounded after the horse, dog on its heels.

Lion Eyes by John Banovich

The short-lived melee may have saved him. Instead of grabbing the man by throat or head, killing him, the second lion had clamped hastily onto his right shoulder. Harry found himself dragged across the rough veldt, belly up, underneath the beast. When he dug his spurs into the earth, it tugged harder, tearing painfully at his shoulder. Shock had not numbed Harry. Escape was a very dim hope. That this predator would start dining before it killed him seemed more likely.

His knife came as an after-thought. He was almost surprised, reaching behind with his left hand, that it hadn’t been lost, as had his rifle. Bouncing in agony through the dark, he found its haft. How to use it? Sticking the 6-inch blade into the lion’s face would spring the jaw. But it wouldn’t kill. The lion would most likely sink those fangs again, this time with lethal result.

As carefully as he could, he withdrew the knife, reached across his body, and with all his might back-handed the blade low into the crease behind the lion’s shoulder. Again, quickly. As the cat dropped him with a roar, he slashed at its throat. The beast stumbled off into the night.

But Harry’s ordeal wasn’t over. Right-arm tendons severed, he was unable to use his hands to set the grass afire to nix another attack. He dragged himself to a low tree and, with great effort, up onto a low limb. There he belted himself in place. Presently he heard the lion’s last sigh.

The faint slip of grass against muscle, of rough breath in tentative cadence followed. Worse news.

Losing its bid for the horse, the first lion had returned to blood-scent. Now it approached along the smears Harry had left crawling to the tree. Terror-stricken, he felt his perch shake under the lion’s weight.

Then Harry heard his dog, full-throated, coming fast. Egged on by Harry’s weak pleas, it harassed the lion off the tree and for a time kept it at bay, dodging those great claws. The sound of rattling tins on the arriving pack donkeys at last sent the animal into the bush. Harry’s men eased him down and did what little they could with no water before plodding on toward the pan.

It was dry, but the staff managed to scrape up enough mud and flotsam to cover Harry’s wounds. By morning these would turn septic. Fever and weakness kept Harry prostrate as nearby villagers carried him to the nearest town, several days’ journey away. The stench of his own rotting flesh bode ill. Nursed from the brink of death in hospital, he began slow recovery. Never again would he lift his right arm higher than could be managed to press a trigger.

His wounds and repeated bouts of malaria nudged Game Ranger Harry Wolhuter into retirement in 1946, ending a 42-year career. He’d been the first to serve South Africa’s Kruger National Park in that capacity. In December, 1964, the durable hunter died on his farm, Lindandene, near Witrivier. He was 88.

His wounds and repeated bouts of malaria nudged Game Ranger Harry Wolhuter into retirement in 1946, ending a 42-year career. He’d been the first to serve South Africa’s Kruger National Park in that capacity. In December, 1964, the durable hunter died on his farm, Lindandene, near Witrivier. He was 88.

“I returned, and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.” So Ecclesiastes distilled fate.

We assume time will spool out at a measured pace until we eventually reach our allotted limit. We learn later that time accelerates with age. We assume chance will coddle the careful. Later we see it bless the reckless.

You might say chance put lions in Wolhuter’s path that night in 1902—and left him his knife and brought his dog back just in time. You could credit chance for saving John Henry Patterson repeatedly in 1898, as the brave engineer pitted his limited hunting skills against two lions eating his rail crews near the Tsavo River. The cats’ diabolical cunning and fearsome lethality should have written his epitaph.

Sitting alone in low, vulnerable machans, Patterson spent many fruitless nights as the lions racked up a total of 28 Indian coolies and uncounted Africans around his camps. Once, with a colleague in a rail-wagon fronting a kraal, he heard the cattle take alarm. A dark form appeared suddenly—and hurled itself at the men! They fired simultaneously. The powder flash and thunderous double report under the iron roof turned the lion in mid-leap.

Soon thereafter, on a beat, advancing coolies pushed a huge lion into Patterson’s rifle sights at 15 steps. Pressing the trigger brought “the dull snap of a misfire.” Terror-stricken, the man forgot his second barrel. The lion regarded him dismissively, then left. Unnerved but undeterred, Patterson built a machan nearby, in what was little more than a bush. That night he awoke in the blackness to hear the lion padding about, a short leap below the flimsy platform. When at last the animal took shape, almost at his feet, he emptied his magazine. One bullet struck the heart. The cat taped nearly 10 feet.

An attack by the second lion prompted another machan, another night’s vigil. Again Patterson felt himself the prey as the animal approached in near silence. At 20 steps he sent a .303 bullet into its chest, firing three more as it retreated. Next morning, the blood trail led Patterson’s party to the wounded brute. He fired. It came. A second shot felled it; but it recovered and ignored a third. Patterson scrambled up the nearest tree just as the lion reached it. A final bullet ended the rail delay at Tsavo.

John Henry Patterson died, presumably peacefully, in 1947, age 79.

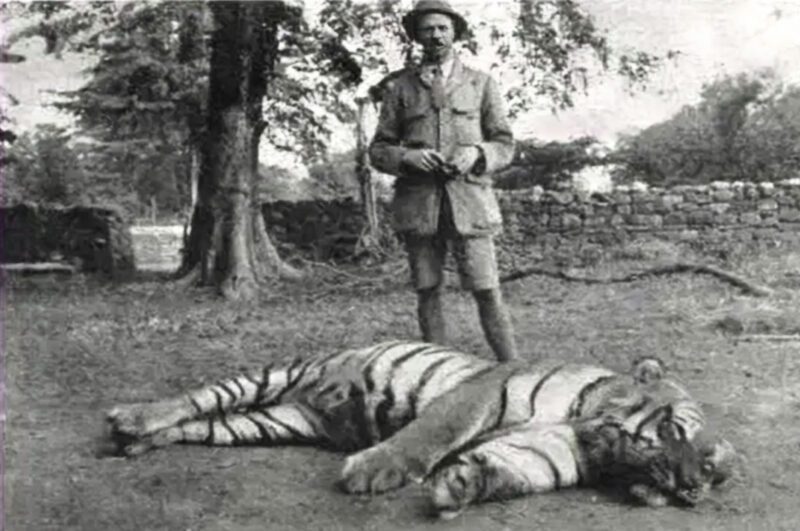

Also 79 at his death, and unmarred, was tiger hunter Jim Corbett, who prowled jungle thickets to waylay India’s man-eating cats. Some of his shots were measured in feet. He passed in 1955.

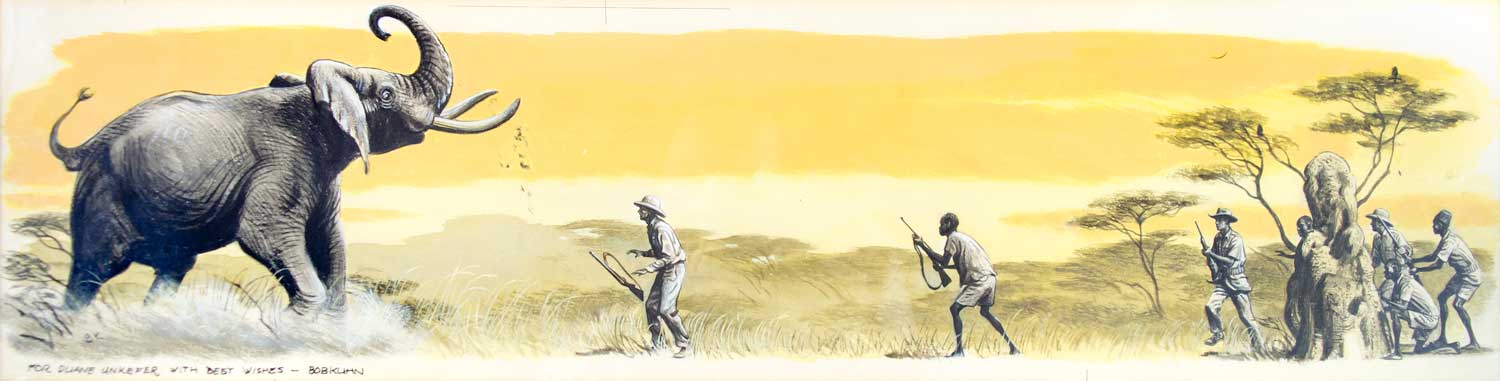

Ivory hunter W.D.M. Bell downed hundreds of elephants with small-bore rifles, some animals in grass so tall he’d climb a carcass to fire at other bulls. He retired intact to Scotland where he engaged in sailing and painting until his death at 73 in 1954.

Philip Hope Percival, a renowned hunter in colonial Kenya, joined Theodore Roosevelt’s 1909-1910 safari and later guided Ernest Hemingway on both of his. Percival lived until his 80th year, 1966.

Professional hunter Harry Selby, born in 1925 at the end of the era of exploration, grew with the commercial safari industry. A stroke of sunny fortune teamed him with Robert Ruark in 1951. Horn of the Hunter drew a stream of clients. He retired at 75 and lived to the ripe age of 92.

On the other side of the globe, in Alaska, creatures and country that also killed hunters left many unscarred. Bill Pinnell and Morris Talifson, hailed as the “last of the great brown bear men,” lived rough for much of their career on Alaska’s Olga Bay. Guiding hunters to the world’s biggest carnivores, often in tight alder thickets, they had close calls but long tenures afield. Pinnell died at 92 in 1990. A decade later Talifson passed, age 91.

Tales of peaceful retirements earn little press. Nor, once, were they common, much less assured. Explorers during the late 19th and into the 20th century went missing. Only a few, such as Livingston, turned up ambulatory later. Losing your way was an endemic risk in new country. Cold and starvation threatened those who probed the arctic for a northwest passage and for Klondike gold. Disease and wild beasts and surly natives claimed others in the tropics. Fortunes in ivory drew reckless hunters to the bush, where rash action could bring harsh penalties.

Chance does not accord all doomed men an honorable finish. For years after East Africa had been colonized by white settlers, the Ituri Forest in the northeast sector of the Belgian Congo was a mysterious place. But adventurers had found its high-grade ivory, also its Pygmies. Exploiting these shy people, who would trade an elephant tusk for a handful of salt, was easy. Still, there were boundaries. One amorous Englishman, whose name rests with him, chased a young Pygmy woman into the forest. Though terrified, she kept her wits and scooted down a trail over a screen of leaves hiding an elephant trap. Her heavier pursuer crashed through to his death on poisoned stakes below.

In the 1930s, PH John Hunter organized an expedition into the Ituri to collect plants and animals for the Kensington Museum. He hired a guide, Bezedenhout, who knew the forest and had obtained the first photos of the okapi, a secretive, giraffe-like creature. This pioneer had also poached ivory and had urged native soldiers to desert and use their military rifles in that effort.

Porters ferried the tusks through the eyeball-deep, croc-infested Semiliki River, a 40-yard gauntlet Bezedenhout cleared temporarily with a hail of bullets. Intelligent and ruthless, observed Hunter, Bezedenhout “might have achieved great heights of power.” Pygmies adored him, as did a countess he’d guided in the Ituri. He refused her offer of wealth, travel and winters on the Riviera with her: “What would I hunt?”

For years after Hunter’s expedition, he asked about Bezedenhout. No news came. He concluded the man had vanished, “somewhere in the depths of the great Ituri.”

Equally enigmatic was a Dutchman named Fourrie, who steered Hunter across Kenya’s Serengeti Plain on his first trip to Ngorongoro Crater. A rhino had hooked Fourrie, mangling one thigh; but a three-month foot safari posed no problem. When enthusiastic shooting depleted the supply of full-jacket bullets, Fourrie pulled softpoints and reversed them in the cases, so they presented the jacketed heel and would drive deeper. In the Crater he led the party to a homestead, where a Captain Hurst lived alone.

They learned Hurst was 10 days dead. His head boy said he’d shoulder-shot an elephant. Trying to intercept the wounded beast, he had come face to face with it. The elephant grabbed him and beat him against a tree. “The bwana screamed and the elephant beat him again. The bwana kept screaming and the elephant dashed him against the tree still harder. Then the bwana did not scream any more so the elephant dropped him and went away.”

John Alexander Hunter would shoot elephants for ivory, lions and rhinos on control missions for the government. He finished his long, eventful career as a PH, retiring whole and passing in 1963, age 76.

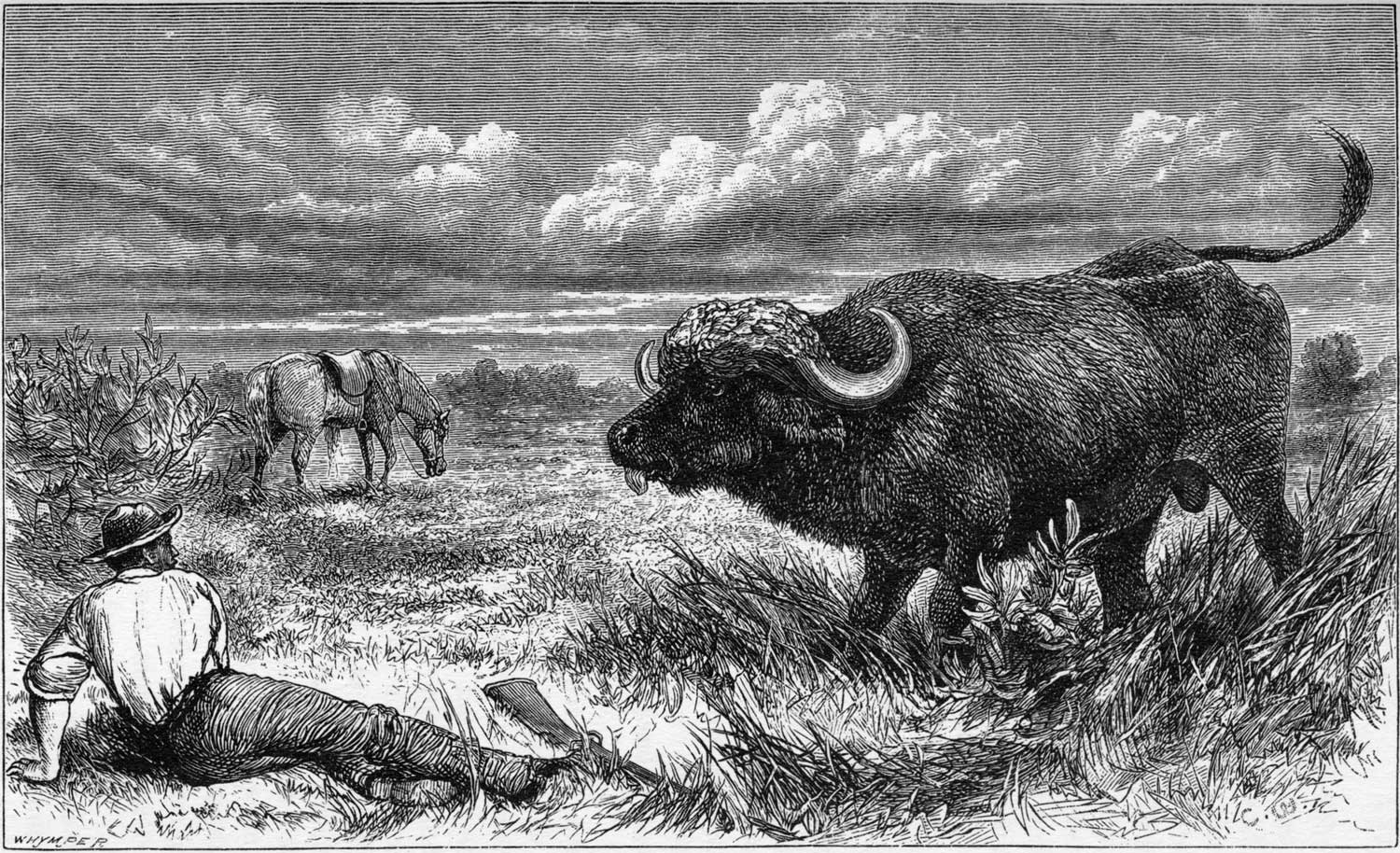

The popularity of hunting Cape buffalo now, with more limited opportunity for other “Big Five” game puts m’bogo near the top of the hazard roster. While unmolested buffalo rarely attack, one did kill veteran hunter and Canadian outfitter Bob Fontana not long ago. Multiple hits can fail to stop wounded bulls, whose size, speed and hooked horns can kill on contact.

In 2012 experienced PH Owain Lewis was struck while reloading after his client had wounded a buffalo that absorbed several hits before reaching the party. Lewis was quickly dead. In 1994 a man named Fraser approached a downed buffalo from the front. The bull lunged, a horn catching the hunter’s leg, tearing his femoral artery. Fraser bled to death.

Stateside, the peril most publicized is the bear. As grizzlies have multiplied in suitable habitat in the Lower 48, so have dustups between bears and people. The protected status of the grizzly makes self-defense by rifle-fire a last-ditch option. A couple of years ago, a hunting guide and his client were tending to a dead elk when a grizzly charged. It killed the guide. Maulings have become an annual statistic in the northern Rockies.

But everywhere, headlines feature the few. Most hunters dodge the hazards of bush and mountain to retire in lesser places. Some expire in events that have little to do with hunting.

George Armstrong Custer found his calling in our Civil War. A brigadier general at 23, he “rode to the guns” with such ardor, 11 horses were shot from under him. Later, in the West, he hunted big game with the same zeal. Custer’s hubris proved more lethal than Confederate bullets or plains grizzlies. On the 25th of June 1876, he and much of his 7th Cavalry fell at the battle of Greasy Grass on the Little Bighorn River. He was 36.

After a perilous but charmed life exploring Africa’s wild places, an error in judgment on January 4, 1917, claimed renowned hunter Frederick Courteney Selous. At age 64, he had re-joined the British Army and been promoted to Captain. Creeping forward in a skirmish against German forces on the Rufiji River, in what is now part of the Selous Game Reserve in Tanzania, he raised his head and binocular. A sniper shot him dead.

Chauncey Hugh Stigand survived a rhino’s lunge that pulped his chest. He pounded with his fists a lion shredding his arm. After a bruising by an elephant, the resilient hunter, then 42, returned to British military service to help stem an Aliab Dinka uprising at Kor Raby in the southern Sudan. An ambush sprung by a great gaggle of warriors on December 8, 1919, spitted Major Stigand and many others of his outnumbered force on Dinka spears.

But battles spare the masses. So chance finds other means. One day in May 1931, Denys Finch-Hatton—British hunter, playboy and, famously, lover of Danish Baroness Karen von Blixen—died when his Gypsy Moth crashed near Voi, Kenya.

On July 2, 1961, Ernest Hemingway, 61, trumped fate—as would Bob Swinehart, the first man on record to kill Africa’s Big Five with bow and arrow. He died by his own hand May 13, 1982, age 54.

Two accomplished bowhunters of my generation were also talented bowyers and might still be at their craft. Montanan Paul Schafer died at 44 in a skiing mishap in 1993. Oregonian Jim Brackenbury and I hunted elk together above the Snake River Canyon shortly before the billows in its belly swallowed him.

Some wild places sequester the remains of hunters dead by chance or error.

Years ago, drawn by the fine walnut on a Henriksen-stocked Mauser at a gun show, I met one of the two men who’d bought more than 400 firearms from the estate of a physician in Alaska. Charitably, the fellow took my deer rifle in trade for the .270 with “RCS” in a raised oval on its wrist.

“Dear Sir, I’ll just bet that you think I’m one funny nut for writing you, but so many of your fine friends are my best friends…Bob Brownell, Thomas Shelhammer, Keith Stegall, Bill Sukalle and Jack O’Connor are my very best friends….”

So began Dr. Russell Smith’s letters to Hosea Sarber, Alaska game warden and hunting guide. In that 1948 note, the Barron, Wisconsin, surgeon had dropped names of the era’s prominent rifle-makers. O’Connor was the only career scribe. “…Mr. Sarber, I’m 43 years of age and for the past 15 years have worked like hell [seeing on average] 105 patients daily…. Now I’d like to [settle] where I could hunt big game…. How are conditions in Alaska for establishing a medical and surgical practice…? My fine wife thinks we would be [happy there] too. Besides her, I’d bring my dog and my technician.” All presumably well behaved.

Smith invited Sarber to visit and use his 400-yard range and “stay a good while.”

I’ve found no record of Sarber visiting. But Smith began sending him rifles. On April 2, 1948, he wrote: “Hosea, [you have] a Remington 721 coming in 300 H&H Magnum, too. I thought you would like one; now that makes:

Remington 721—.270

Remington 721—300 H&H Magnum

Winchester Model 70 in .270

Winchester Model 70 in 220 Swift heavy barreled Target.

These are all going to you from me as presents.…”

A year later: “Won’t be long before that 23-inch .375 Magnum is in your hands, Hosea….”

And July 17, 1950: “I wrote Winchester…and ordered three rifles in the sporting style and two .220 Targets, one for you and the other for me.”

Hosea Rollo “Bigfoot” Sarber was born on my birthday a few decades earlier. Raised on a farm near Tyner, Indiana, he lost his left eye as a child in a saw accident crafting a wooden gun. He would later credit his marksmanship to an exceptionally keen right eye. At age nine, he and a pal sent Sears, Roebuck a letter and $3.75 for a single-shot .22 rifle. Sixteen years later he was bound for Alaska. There he earned credentials as a hunting guide and was subsequently hired by the state’s wildlife commission. He joined the 1935 search for the ill-fated airplane carrying Will Rogers and Wylie Post.

A rifle enthusiast, Sarber “started with the old 30-40 Krag.” On seal-control shoots for the state, he used heavy-barreled bolt-actions in 22-250, 220 Swift and the wildcat 220 Arrow, many topped with 10x Lyman target scopes. He favored Lee Dot reticles in these and in the Lyman Alaskans on his hunting rifles. Sarber liked the .270 and .30-06, handloading 160-grain Barnes bullets and 172-grain Open-Points from Western Tool and Copper, respectively. Guiding hunters, he packed a .375 and was reported to own nine Winchester M70s in that chambering. Sarber also stocked rifles. A visitor to his Pertersburg, Alaska, office counted “no less than 50 blanks” awaiting inletting.

His responses to Smith’s letters and gifts have eluded me. So have the circumstances of his death.

Sarber was renowned for his bear-hunting prowess. Early in his career, he’d visited Eliza Harbor to investigate the 1929 killing of timber cruiser Jack Thayer there months earlier. At that time, Slayer was the only person confirmed as slain by a brown bear on Admiralty Island—albeit the species was famously abundant there. Near where Thayer had perished, Sarber was reportedly charged by a bear. Scrambling up a windfall, he shot the animal.

Three decades later, in a letter dated May 14, 1951, Dr. Smith wrote of his imminent move north. “Dear Pal Hose: [Thursday I] shipped 19 boxes of rifles via express and the Alaska Steamship Company…have disposed of my home and am closing out my practice as of June first….” He repeated his interest in bear hunting, though to photograph, not kill. He had shot four brown bears.

Just over a year after Smith’s arrival, on July 28, 1952, Hosea Sarber left Petersburg on patrol for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. He was never seen again. An investigation yielded no solid evidence. Speculation had it he ran afoul of fishermen poaching in closed waters; but his hunting exploits kept bears in the campfire chat. A human skeleton was reportedly found several years later in a remote place within the range of his patrol boat. A 33-caliber 1886 Winchester and a S&W .38/44 Outdoorsman turned up on site, too, as did the remains of a bear. The rifle was empty; the revolver’s cylinder held empty cases. Sarber? The man’s strong preference for bolt-action rifles argues against that conclusion.

In the Tyner Cemetery, Marshall County, Indiana, a cenotaph bears Hosea Rollo Sarber’s name.

Hunters these days face fewer perils. GPS units and smart-phones tether them to help and safety. ATVs bring them where once they had to walk, and back out again. Miracle-clothes keep weather at bay. Powerful loads not only kill, but stop aggressive animals.

Still, bush and crag have no regard for predictions. And only the stories live on. Hunters find, in the final sift, that indeed time and chance happeneth to them all.