Some of the finest shotguns ever made in America were hammer shotguns produced in the last decades of the 19th century. However, by the end of World War I, most had been retired to gun cabinets to be only admired, not fired. Their barrels had not been designed for the more powerful nitro-based cartridges.

The Parker Story by Lewis C. Parker and others published in 1998 concluded its chapter on hammer doubles with the following observation:

“In the United States, the last three decades of the nineteenth century were The Golden Age of Shotgunning according to Bob Hinman in his interesting book by that title. The Parker Brothers Gun Works was in the thick of it. Game was plentiful, game limits and seasons were non-existent or generous, trap shooting was popular, and a few shotguns were needed by the ‘shotgun messengers’ riding the western stagecoaches…. The Parker Brothers hammer doubles are no longer seen in the field…bringing down game. When they are seen today, they are more likely in a collector’s display, exemplifying the pinnacle of the American gunmaker’s art and craft from times past.”

A lot has changed in the past 20 years. Interest in vintage hammer shotguns has revived, driven by the growth of vintage gun shooting societies, the popularity of sporting clays and availability of high-quality, factory-produced, low-pressure shotgun shells. This new specialty ammunition gave these guns a new life on the range and in the field hunting upland game. The introduction in the past few years of low-pressure shells with non-lead shot have also brought hammer guns back to waterfowling.

Classic hammer guns are a joy to shoot. Handling a finely crafted 19th century hammer gun is an entirely different experience than handling a modern semi-automatic or pump. Classic hammer guns have excellent balance, mount easily and point naturally. Many are also beautiful works of art.

Hunting waterfowl or upland game with a 19th or early 20th century hammer gun connects us to our past, preserves a part of our hunting heritage and brings us closer to the environment and the game we hunt. It is a somewhat greater challenge for the hunter and a fairer chase for the game. The experience is analogous to hunting deer with a traditional muzzleloader. As a result, wingshooters today have an opportunity for a new and rewarding hunting experience.

The word “classic” is used to convey that something: (1) has come to exemplify the best of its kind or class, (2) has a timeless quality of beauty or design and (3) has been popular or otherwise valued for a long time. The five models of hammer shotguns described below meet these criteria, each in different ways.

Parker Brothers Top-Action

The Parker Brothers was the first American company into the market with a commercially successful breech-loading cartridge shotgun. Its guns were also the most expensive among the major manufactures throughout the late 19th and early 20th century. All Parker hammer guns manufactured between 1869 and 1881, which went through four different designs, used a lifter bar placed just forward of the trigger guard to break open the gun. These are commonly referred to as Parker “Lifter-Action” hammer guns.

In 1882 Parker introduced a new model shotgun with a top-lever release. This gun also incorporated other new technologies, including a doll’s-head top-rib extension and redesigned barrel locking lugs. Parker stayed with this design, which it called “Top-Action,” for the next 35 years, manufacturing 36,400 guns.

Parker made Top-Action guns in seven grades. In 1882 the cost of a 12-gauge in Grade 0, 1, 2 and 3 was $55, $70, $80 and $125, respectively. The cost of a 10-gauge was $60, $75, $85 and $125, respectively.

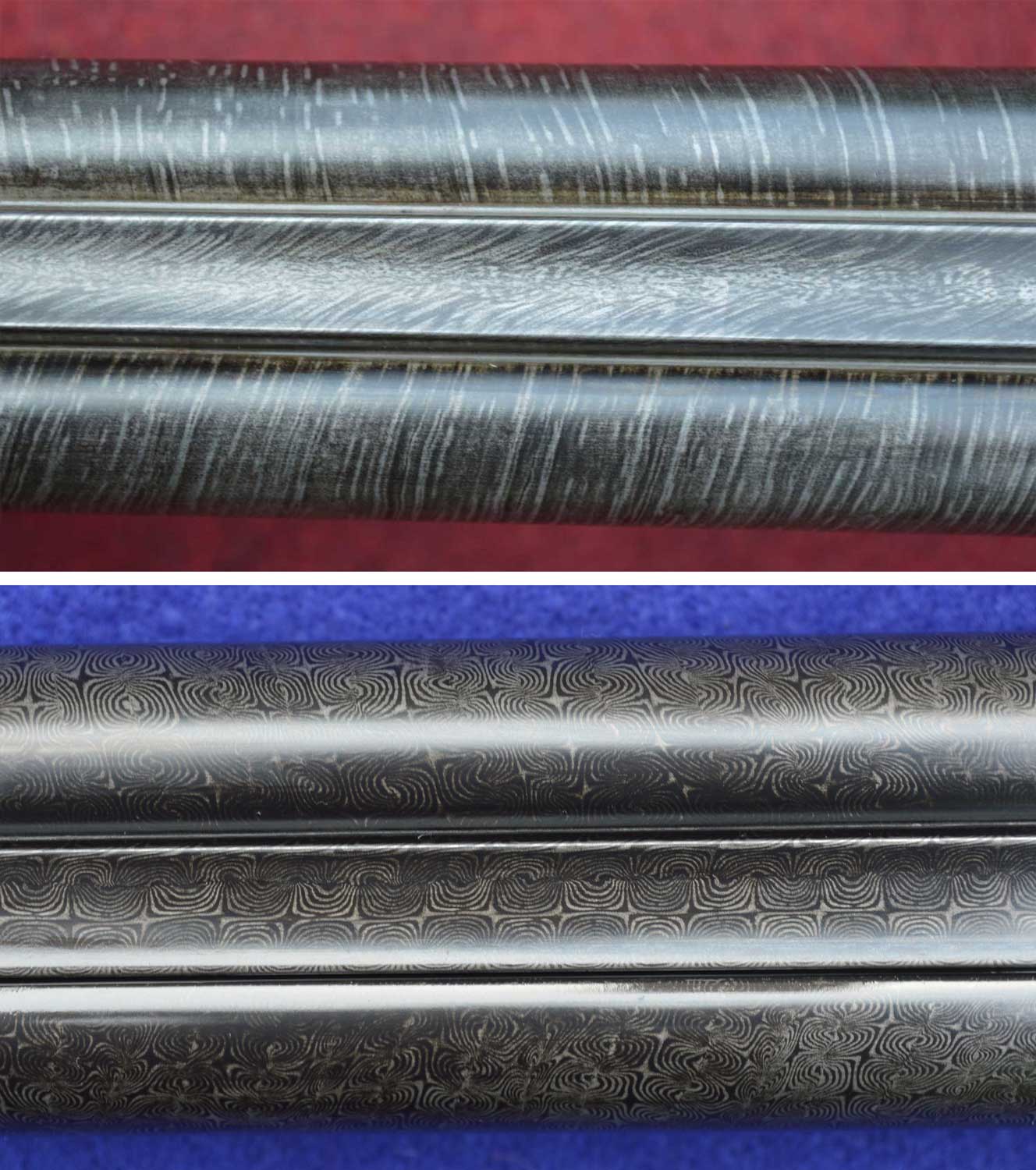

The barrels of the Grade-0 gun above are made of twist steel. The barrels of the Grade-2 gun below are made of Damascus steel.

The barrels were the most expensive part on all 19th century American hammer shotguns. Parker used twist steel in Grade 0 and Grade 1 guns, standard Damascus steel in Grade 2 guns, fine Damascus steel in Grade 3 guns and extra-fine Damascus steel or Bernard-steel on Grade 4 and above. Parker and all other American manufactures imported their twist, laminated and Damascus-steel barrels from Europe.

The Grade-2 Top-Action 12-gauge above, which was manufactured in 1883, sold for $80 at a time when a skilled machinist made 25 cents an hour.

As a percentage of total production, 12-gauge guns constituted 60 percent, 10-gauge 36.5 percent, 16-gauge 3 percent and other gauges 0.5 percent. The most common barrel length was 30 inches (59 percent) followed by 32 inches (32 percent), 28 inches (7 percent) and all others (2 percent). The chamber lengths of 12-gauge guns are 2 5/8 inches, 10-gauge are 2 7/8 inches, and 16-gauge are 2 1/2 inches.

Grade-3 Top-Action guns, such as this 1887 12-gauge, have enhanced engraving, fine Damascus-steel barrels and English-walnut stocks.

Of Top-Action total production, 64.5 percent were Grade 0 (also referred to as T-Grade), 11 percent Grade 1, 20 percent Grade 2 (also referred to as P-Grade), 4 percent Grade 3 (also referred to as D Grade) and 0.5 percent Grades 5 to 7. As these numbers show, Parker Brothers was sustained largely by the sales of its field-grade guns. The same was true for the other premium shotgun manufacturers, which is one important factor in terms of availability and condition of guns that are most available to today’s shooters and hunters.

Only about one in 20 guns made by Parker were the higher-grade guns and most have been in the hands of collectors for a long time. When they do become available, they are expensive. Parker field-grade guns, however, are regularly available and reasonably priced. After reconditioning, they can be very handsome. They are functionally identical to their higher-grade counterparts and shoot just as well.

Parker Top-Action guns were prized in the 19th century and continue so today. Arguably, a greater percentage of Parker Top-Action guns have survived than any other American hammer gun, with one possible exception.

Parkers are always well represented at local vintage shotgun events across the country and at national vintage hammer gun competitions. It is past time for them to again be “seen in the field…bringing down game.”

Colt Model 1878

The Colt Model 1878 is for many the iconic image of a 19th century American hammer shotgun. A sound-bite characterization might well be “a combination of London’s Best and the Wild West.” Herbert Houze concisely captures in a 2005 Double Gun Journal article one of its principal attractions: “Even in its plainest forms, the Model 1878 possessed an elegance and grace equal to that of the best made English shotguns of the period.”

The Model 1878 symbolizes for many people today the classic American hammer shotgun. The reconditioned standard Grade-8 here cost $62 when manufactured in 1881.

Colt’s Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company’s foray into the double barrel shotgun market was brief, from 1878 to 1891. It produced approximately 23,000 Model 1878 shotguns. Targeted to a very limited and competitive market, the Model 1878 was not a financial success.

The 10-gauge Model 1878 Grade-5 gun above (SN 3848 manufactured in 1880) has a short tang and lacks a top-rib extension.

Colt offered the Model 1878 only in 10- or 12-gauge. It advertised seven variations of standard production mode, which basically cluster into three different quality levels. Grades 1 through 4 were field-grade with twist barrels and no engraving. They were priced at $42 in 12-gauge and $50 in 10-gauge; those with a pistol grip cost $4 extra. Grades 5 and 6 were an intermediate-quality gun with line engraving and laminated-steel barrels. They were priced $8 higher than the field-grade guns.

Design flaws are corrected in the 10-gauge Model 1878 Grade-8 gun above (SN 12629 manufactured in 1882).

The early Model 1878s had a short tang and only one screw secured it to the stock. The heavy barrels, especially of 10-gauge guns, produced too much vertical stress at the wood-receiver interface. Consequently, many of the surviving early guns have damaged stock heads. The early guns also lack a doll’s-head top-rib extension. Without the added strength and stability to the receiver-barrel interface, some early guns that come available today have excessively worn barrel lugs and locking bolts. Both problems can be repaired, but at some expense.

The Model 1878 shoots well for people who require a lot of drop for their best-fitting stock, or can adjust to it. This is probably not the reason, however, why a disproportionate number of Model 1878 shotguns have survived.

The original buyer of the Grade-8 gun in this picture paid an additional $30 for its enhanced engraving.

Its iconic status and high survival rate can be attributed in part to its association with the Wild West. To a degree, this association is part of the Colt brand. And Wells Fargo did have men “riding shotgun” with Colt 1878s on some of its stagecoaches, but it also used other guns. The public’s connection of the Model 1878 with the Wild West seems to have largely emerged from early 20th century Western novels and solidified in 1950s movies.

Remington Model 1889

The Model 1889 was the best-seller among classic American hammer shotguns. The Remington Arms Company manufactured 134,000 between 1889 and 1910. The story behind its success is in some ways the story of the early years of sporting arms manufacturing in the United States.

E. J. Remington and Sons, the precursor company to the Remington Arms Company, entered the new market for breech-loading shotguns with its Model 1873. It is similar in design to contemporary British guns, except for its thumb-push release. At the Grade 3 level and above, the quality of the Model 1873 compares well to similar grade guns manufactured for the American market by British firms such as W. & C. Scott and W.W. Greener. However, the few Americans who could afford such quality, the one-percenters of the Gilded Age, tended to buy British shotguns as a mark of wealth and status.

E. J. Remington & Sons introduced updated models in 1875, 1876 and 1878, producing about 20,000 guns over nine years (eight guns per 12-hour workday, six days a week). In 1882 it produced a new model incorporating the top-action release, pistol-grip stock and lower hammers popular in America. It introduced slightly modified versions in 1883, 1884, 1885 and 1887, producing a total of approximately 23,000 shotguns between 1882 and 1888.

The Model 1882 incorporated a top-action release, pistol-grip stock and lower hammers popular in America.

E. J. Remington & Sons, a successful family business since 1816, went bankrupt in 1888. It was acquired by Marcellus Hartley who owned one of the most successful guns and sporting goods catalog-sales companies. Hartley took the renamed Remington Arms Company into the industrial age of mass production and marketing.

Under Hartley’s guidance, Remington Arms Company incorporated the best aspects of E. J. Remington’s shotguns into a single unadorned, rugged and attractive gun that shot well—the Model 1889. Remington Arms Company had a winner and stayed with it for the next two decades. Within three years, Model 1889 sales were averaging around 6,000 guns a year, peaking in 1901 at 15,500.

Remington’s Model 1889 was the best-selling and most rugged of the classic American hammer guns. The reconditioned Grade 3 above and at left has 32” Damascus-steel barrels and weighs 8 lbs. 8 oz.

Only three grades of gun came off the Model 1889 production line, the principal difference in quality being in the barrels. The barrels of Grade 1 guns were made of decarbonized steel, Grade 2 of plain twist steel and Grade 3 of standard Damascus steel. Grades 1 through 3 guns were not engraved. The nicely engraved Grades 4 to 6 guns were made only by special order and are today rare. Grades 1, 2 and 3 guns originally cost $40, $45 and $55, respectively.

The Model 1889 is a sturdy and reliable gun, which is probably why it can be found today in all three production grades. Given the number of guns sold, its durability and its introduction at the height of the Western expansion, the Model 1889 has probably killed more game than any other classic hammer gun.

L. C. Smith F Grade

The L. C. Smith hammer gun was introduced in 1884, when L. C. Smith guns were being made in Syracuse. It was offered in a range of grades and prices from Quality AA for $300 to Quality F for $55. About 5,500 L. C. Smith hammer guns were made before the Hunter brothers brought production to Fulton, New York.

Between 1895 and 1932, Hunter Arms produced in Fulton approximately 82,500 hammer guns. L. C. Smith hammer shotguns had the longest run of any of the classic hammer guns. It is also the only classic American hammer gun that was manufactured with fluid steel barrels, which is one reason for its popularity today.

Hunter Arms outlasted its competition largely because it best adapted its hammer gun to the changing market conditions at the end of the 19th century. In 1898 Hunter Arms cut production dramatically of its line of expensive graded hammer guns. In order to compete successfully with the mass-produced low-price doubles and the new class of single-barrel pump shotguns, the company focused on one new hammer gun, the F Grade. The new F Grade was offered in three “styles” based on type of steel used in the barrels. The least expensive, which had fluid steel barrels made in nearby Syracuse, sold for $20. It quickly became a best-seller.

The L. C. Smith Model F shoots well for many people. While commonly available today, guns in high original condition,

such as the 12-gauge in these two photos, are scarce.

The F Grade is a nicely balanced gun that has many advocates. Its fluid steel barrels make it the only classic American hammer gun in which standard target and field loads can be used safely. Post-1898 F Grade guns are commonly available at a reasonable cost. However, as is the case with most field-grade guns, many need reconditioning before being fired.

The comparative shooting qualities of the L. C. Smith F Grade hammer gun and the Parker Brothers Top-Action play out every spring during the Southern Side-by-Side competition at Deep River Sporting Clays in Sanford, North Carolina. The Parker Brothers vs. L. C. Smith hammer gun competition, which is sponsored by the respective collectors’ associations, is one of the highlights of the event.

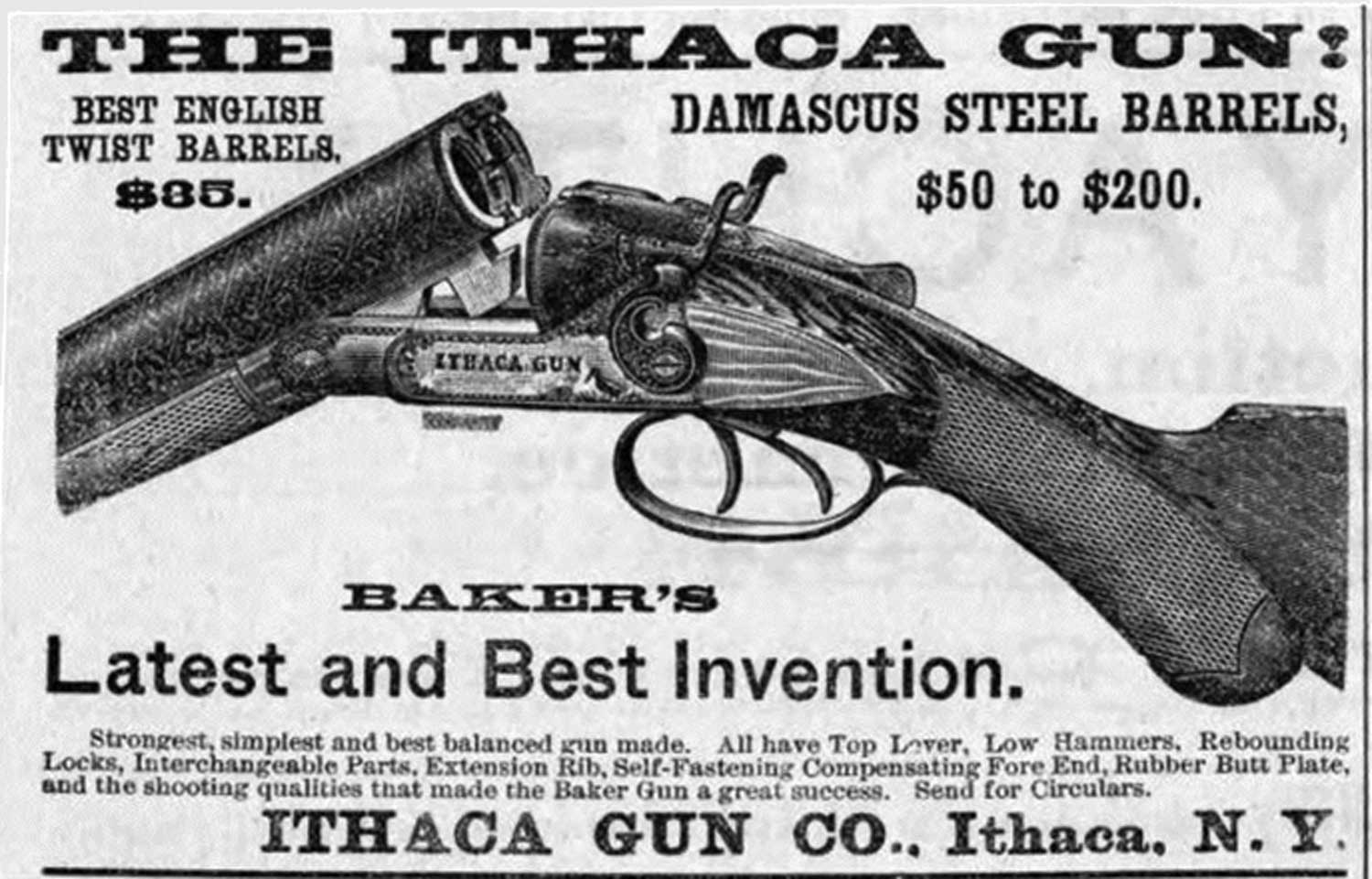

Ithaca NIG (New Ithaca Gun)

The place of the Ithaca Gun Company hammer shotguns on the short list of classic American hammer guns is secured by two factors. First, the Ithaca NIG and its immediate predecessor, the Baker Model, launched and for two decades sustained what is today one of America’s major firearms manufacturers. Second, Ithaca hammer guns are unique in that they are the only boxlock American hammer shotguns manufactured in significant numbers in the 19th century.

The inventive genius behind the Ithaca hammer boxlock was W. H. Baker, who left the L.C. Smith company to become one of the founders of Ithaca Gun Company. The Ithaca Baker Model sold about 6,500 guns from 1883 through 1887, when W. H. Baker left Ithaca to found the Baker Gun Company. The need to differentiate Ithaca shotguns from those produced by Baker’s company was the impetus behind the NIG.

Among classical American hammer shotguns, the NIG is the only boxlock. This reconditioned Ithaca NIG 12-gauge has 28-inch twist steel barrels and weighs 7 pounds 6 ounces.

Ithaca made mechanical and visual modifications to the Baker Model and named the gun, quite logically, the New Ithaca Gun. It produced 35,200 NIG hammer guns from 1888 through 1914, almost all being Quality A, or field-grade, guns. It had English-twist barrels and cost $35.

The Quality A NIG is a very nice field-grade gun, on par with a Remington Model 1889 Grade 2. Both are unadorned and not expensive, but shoot and hunt well. However, the percentage of NIGs that have survived appears to be disproportionately lower. One possible explanation is that its first generation boxlock mechanism proved less durable than the time-tested sidelock mechanisms used in Remington, Colt, Parker and L. C. Smith Type I hammer guns.

In Recognition of the American “Affordables”

The classic hammer guns described here were the best of class and have withstood the test of time. They continue to be admired for their beauty and valued for their shooting qualities by sportsmen. This does not, however, diminish the importance of hammer shotguns that were affordable for the average American.

During the first two decades of the 20th century, the “Golden Age” of shotgun manufacturing was ending and the age of American mass-produced shotguns was taking off. Classic hammer shotguns by premium manufactures were the first casualty. By 1918 hammer gun production had ceased entirely at Remington, Ithaca and Parker Brothers; Hunter Arms continued making a limited number for another decade.

However, demand for less expensive hammer guns, which were seen as an essential tool of a farmer or rancher, remained strong in rural America into the 1930s.

It was met primarily by H. & D. Folsom Arms group (Crescent Fire Arms, American Gun Company, Norwich Firearms, others) and the Stevens group (J. Stevens Company, Riverside Arms and Springfield Arms). Their field-grade double-barrel hammer guns continued to be used to put food on the table and control predators for at least another generation after production ended in 1934.

These American “affordables” or “everyman’s” guns served the needs of their owners well. Although generally not considered to be classic guns, they left their own legacy. With reconditioning, many of those that have survived can be given a new life back in the field alongside the classic hammer guns—a topic for another day.