Man or woman, dog or gun, you never know when you might say goodbye.

Fixing to write this down before I forget, the days and years slipping away the way they do, that blaze of autumn to water the eye, the flames of maple and oak and the dry-bone rattling aspen, that red and yellow glory, the black spruce and white pine, green pickets between. Me and Deuce and Maggie taking our ease on that pioneer rock pile, on that ruined homestead just north of Debs, Minnesota, population five, a good long time ago.

Maggie was a footsore young spaniel, greenest of a kennel of six. She was thirsty and, at long last, working close to the gun. We gave her water, but not much. We passed sandwiches around—brown bread, pink bologna, and yellow cheese. Maggie got the crusts and nosed our hands and pockets for more, but there was no more.

This land was free for the asking but came with a price few could afford. Finns and Norwegian homesteaders lasted a generation, sometimes two, all their sweat, tears, and blood for naught. And now there was a fallen-in fieldstone basement, a half-dozen winter-blasted apple trees, a broken wood range, a forlorn hay rake, a derelict plow—the sad and rusted remains of a hopeless dream grown into windbreak wood. Three million acres lost for taxes, and two old friends slap in the middle of it, footsore like the spaniel, taking their ease upon rocks grubbed and rolled by hand so long ago.

Deuce had his 16-gauge Ithaca 37; wouldn’t shoot anything else. It fed and emptied through the bottom—some tricky mechanics—and how it worked so well is a continuing wonderment. Deuce had a rack of 37s in various gauges, right down to a 20 that he would rather oil and admire than shoot.

Deuce fished for walleyes, nothing else. He picked wild morel mushrooms every spring. He shot pheasants and more ruffed grouse than any man I ever knew, but never drew a bead on a duck. And deer? No antelope or moose need apply. He had nine whitetail heads above his fieldstone fireplace, and you could put my biggest rack inside his smallest rack and rattle it around. I called it the Supreme Court.

I had my Model 12 Winchester 20 gauge. I wouldn’t shoot anything else, either. It was a lovely gun till you looked close in full sunlight and saw the wire brush marks on barrel and action, and I reckon that was the reason I could afford it in the first place. It jammed only once, when I tried to force feed it a Bic lighter in the midst of a furious rise of Hungarian partridge, busted loose among the haystacks on the far end of a stony field.

The wind was soft and fine and smelled like fresh-cut grain. Making barley that time of year, and way out on the prairie, distant combines hummed and hammered and a yellow haze hung low over the west. But the immediate ragged hills grew only bumper crops of granite and grouse.

Each May for the last 50 years, wildlife biologists with clipboards and No. 2 lead pencils drove backroads along prescribed routes, stopping at prescribed stops and listening for prescribed minutes, noting the drumming of ardent males, the ghostly beatings of wings atop the hollow spruce deadfalls, more felt than heard, like Ojibwe tom-toms, like some pioneer John Deere lugging a plow through heavy, black bottomland clay. It seemed a damn-fool way to count grouse numbers, and the wisdom of such was widely jawed and adjudicated whenever bird hunters gathered in barroom or café, where the intemperate suggested a porcupine pellet count instead.

But it worked. That year it was 1.4 thumps per stop, if memory serves. And that was good enough for us. Deuce had four birds and I had three, and we knew we would pick up one more on the walk to the pickup, back where the road played out a mile or more away. Oh, what country that was, and what times we had in it.

And it came to pass in those days, an ancient Norse custom was practiced upon the Winter Solstice, the almost-virgins prowling the land looking for men with big woodpiles, as they had since the days of Ragnar the Unwashed, the great Viking king. Perilous times for single men of sufficient means and negotiable leisure— Hey, baby, you got any rolling papers? There was an opposite and equal reaction upon the melting of the ice and the greening of the grass, after long months cooped with a less-than-perfect match. The Spring Run-Off, we called it.

Lord knows Deuce loved Lena, but sometimes loving till it hurts just hurts worse. Fine-boned, blonde, blue-eyed, and freckled, she was a jaw-dropping Nordic beauty, but there was something broken way down deep inside. Lena had a twin sister who took to running with a rough crowd and died in an auto accident that maybe wasn’t an accident at all. Lena would visit the grave on the anniversary of her sister’s death, and then there would be hell to pay. Popping pills, slugging whiskey, falling down stairs, several pickups smashed, steaming and gurgling upside down in ditches and sloughs, and Deuce following up the trail, not knowing at each curve if his beloved was alive or dead.

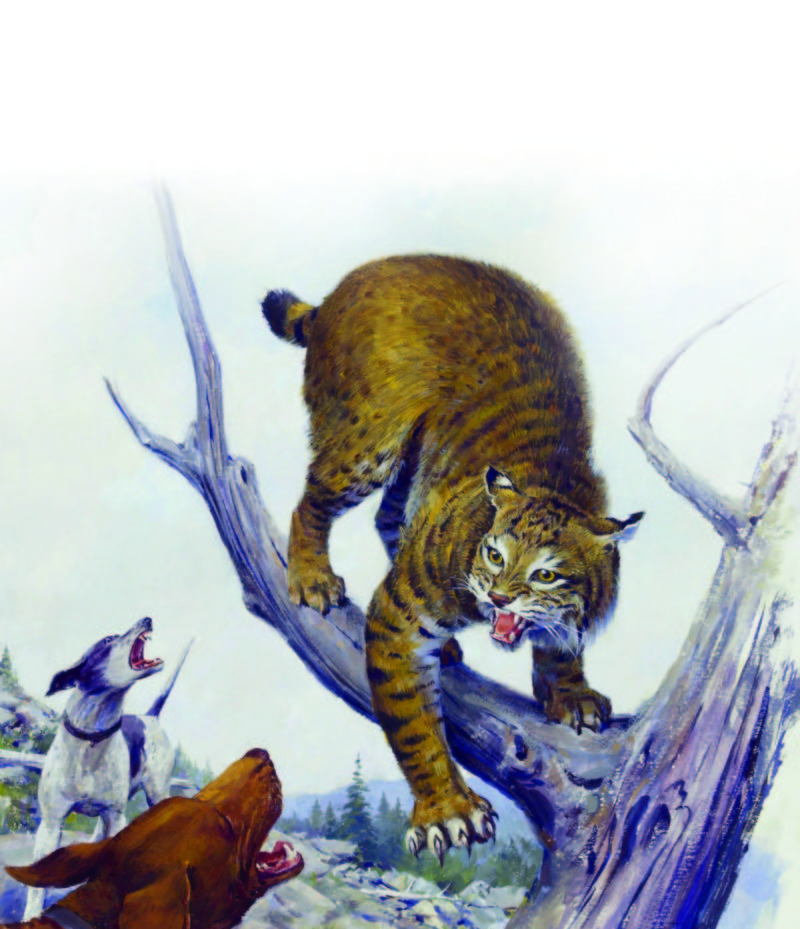

Lena got the house and the dogs. Deuce got the shotguns, the bills, and the Supreme Court. Lena was his favorite hunting companion, and I don’t think he ever shot grouse after that. Deuce never took another wife, but he found new sport in trailing bobcats in deep snow with long-legged Walker hounds.

If you don’t know Walker dogs, you should. Sprung from English foxhounds imported into Kentucky in the 1850s, the Walker is an heirloom American breed. White with liver and black spots, fearless, fleet of foot and keen of nose, floppy ears and jowls to waft the scent. Deer, bear, coon, or cat, the Walker is your go-to hound. A coon-broke Walker will never trail a deer, and a deer-broke Walker will never tree a coon. And you will learn the lingo: the eager yip when you cast them, the eruption at each fresh jump, the chorus on the trail, the chop-chop when they tree or bay.

Bobcats are sure-footed but deliberate, and when the dogs get close, they take to the most convenient tree. I was long gone by then, back to Carolina where I was born and raised, but Deuce sent me a picture. He stood about 5’8”. He had the cat in a hammerlock chin to chin, and the cat’s back paws drug the snow. He never said what it weighed, but it was near-bouts as big as a leopard.

If any man ever died of a broken heart, Deuce did. They found him in a chair in a ratty little apartment east of town. There was a pistol by his side, but he never used it. Though he had trouble making groceries and rent in his last days, he never sold his guns, art, knives, or decoys. He had lost too much already.

He had no children, and the auction fetched up $80,000. No sale on the Supreme Court; those magnificent racks still hang in a pool hall 50 miles east of Fargo, where he went for coffee, burgers, and games of snooker. I’ll be stopping in if I ever pass through that country again.

You heard it said a man sees his life flash before him as he dies? I hope Deuce saw it again, that happy day with a sunset gold from harvest dust, when our vests swung heavy with birds as we picked our way through the fieldstone pasture, downhill toward the truck a mile or more away.

Zip Zap is a wonderful true-life story of a superb English setter and its litter-mates. On the heels of his highly-acclaimed novel Jenny Willow, Mike Gaddis reaches again into a half-century love affair with pointing dogs and upland birds to retrieve the true-life story of Zip Zap, his greatest English setter. Gaddis swore to be painfully selective in choosing the puppy that would accompany him as he pursued his dream of competing in horseback field trials. He knew the smallest female of the litter was special, but he didn’t fully realize her potential until he let her loose in the field. Her lightning speed earned her the name Zip Zap, and she grew to be the most brilliant bird dog Gaddis ever owned. In this absorbing memoir, Gaddis celebrates the dog’s indomitable spirit and tells the story of training and developing a superior pointer, from her first unrefined runs in the amateur puppy stakes to victorious performances in major championships. Evocatively told and set against the plantation quail hunting and field trailing legacy of the Old South, here is a rich, powerful memoir, certain to gain favor with anyone who has shared the destiny of a once-in-a-lifetime dog. Buy Now

Zip Zap is a wonderful true-life story of a superb English setter and its litter-mates. On the heels of his highly-acclaimed novel Jenny Willow, Mike Gaddis reaches again into a half-century love affair with pointing dogs and upland birds to retrieve the true-life story of Zip Zap, his greatest English setter. Gaddis swore to be painfully selective in choosing the puppy that would accompany him as he pursued his dream of competing in horseback field trials. He knew the smallest female of the litter was special, but he didn’t fully realize her potential until he let her loose in the field. Her lightning speed earned her the name Zip Zap, and she grew to be the most brilliant bird dog Gaddis ever owned. In this absorbing memoir, Gaddis celebrates the dog’s indomitable spirit and tells the story of training and developing a superior pointer, from her first unrefined runs in the amateur puppy stakes to victorious performances in major championships. Evocatively told and set against the plantation quail hunting and field trailing legacy of the Old South, here is a rich, powerful memoir, certain to gain favor with anyone who has shared the destiny of a once-in-a-lifetime dog. Buy Now