The rustle of fallen white oak leaves littering the ground 30 feet below demanded my immediate attention. There, patches of brown moved. A deer! Heartbeat racing! Breathing? I am not certain I even took a breath.

A solid hour before first light and under the cover of moonless darkness, I had crawled nearly to the top of an ancient, eastwardly leaning oak—my deer stand. Perched on the 2×4 nailed between two limbs, I settled on the two-inch wide board then pulled up my gun.

In the pocket of my Army surplus camo were two 00 Buck shotgun shells. I broke open the 12-gauge single-shot shotgun that had belonged to my maternal grandfather, A. J. Aschenbeck. He had named it the “Roar.”

Autumn Buck by Walter A. Weber. Watercolor and gouache.

A.J. “Fotta” Aschenbeck, my hero and mentor, had passed away five years earlier and I had talked my Uncle Herbert into letting me use the gun during the 1961 Texas hunting season. I slid one of the shells into the chamber and pulled the other out of the pocket and stuck it in my mouth held securely by upper and lower jaws where I’d have quick access to it should I need a second shot. I was ready!

To the east was not the slightest hint of the coming sun and Dad’s coonhounds barked hoping to be released for a chase. They did not know the whitetail deer season opened this morning 30 minutes before sunup. It would be six more weeks before they would again be trailing and treeing ’coons.

With dawn’s awakening, imagined grizzly bears and buffaloes morphed into small cedar trees and yaupon bushes. Robins and mourning doves greeted the gray as it turned to daylight. Overhead, snow geese winged their way south to the Texas Gulf Coast Prairie escaping the cold and hunger of the Far North and opening of hunting season was mere seconds away.

I repositioned the extra shell to the right side of my mouth where I could more quickly grab it. The rising sun brought squirrels from their hollow tree dens, scurrying about sounding like deer in the leaves. In the distance was a shot, and the whitetail season was open! I tightly gripped the old single-barrel.

“Please, please, please may this be the day I finally become a successful deer hunter!” I near whispered in prayer.

To my left—footsteps. Brown movement. A deer! A quick glance at its head. A buck! Not only a buck, but the buck of a lifetime. A monster. Huge! Boone and Crockett-class, no doubt, maybe even a world record! He was coming my way. I sat mesmerized. I was finally going to have a chance at a buck, and what a buck he was.

The old single-barrel came to shoulder as the buck strode forward, now nearly below my stand. I sighted down the barrel, small bead at the muzzle more or less in the notch on the receiver. I pulled hard on the trigger. Nothing happened. I panicked and nearly dropped the shell from my clenched jaws. What to do? What to do?

Breathe. Oh no! I had not cocked the hammer. Thumb quivering, I pulled it back with a metallic click. The buck stopped. He stood slightly to my right. I sighted down the barrel resting the bead in its notch, the muzzle wandering all over the monstrous buck’s shoulder.

I pulled the trigger. Recoil cracked backward and I saw the buck of all bucks go down!

Then, just as quickly as he had gone down, the world record whitetail was up and running away.

My mind short-circuited, but then remembered, Reload. Reload. Reload! Left hand gripping the “Roar’s” forend, right hand on the action and buttstock, I thumbed the lever and tugged so hard that I pulled the forend off releasing the barrel to freely tumble end over end to the ground, 30 feet below.

There I sat, forend in my left hand, buttstock and action in my right hand, 00 Buck shell grasped tightly in my mouth, gun barrel stuck in the ground below and the world record whitetail buck running away.

I seriously considered jumping out of the tree. Thankfully, reason returned. I half-crawled, but mostly fell as I scrambled down the tree and then ran to where my shotgun barrel was stuck into the soft soil. I raised the barrel to my mouth and blew the dirt out of it, then shakily reassembled my shotgun. The “Roar” back together, I pulled the slobbered on shotshell from between my jaws, slid it into the chamber, closed the shotgun then trotted in the direction where the buck of all bucks had disappeared!

I looked far ahead fully expecting to see a disappearing white flag. I did not look toward my feet and stumbled over something, nearly fell and anxiously turned to see what I had tripped over.

Oh my gracious! Thank You, Thank You, THANK YOU Lord! There lay the buck of all bucks, one with the biggest antlers in the world, no doubt!

My eyes slowly drifted from my buck’s body to his head. In total amazement I watched the world record whitetail buck’s antlers shrink to spikes—a five-inch-long right beam and four-inch-long beam on the left!

It’s a memory I will never forget!

I started seriously hunting deer with my dad when I was four years old, sitting at his side in ground blinds we made with logs and limbs. After my sixth birthday, I hunted by myself. My deer rifle was a single-shot .22 bolt-action, loaded with a 22 Long Rifle hollow-point cartridge.

Back during those days, our part of Texas had very few whitetail deer. If you saw a deer, any deer, during the hunting season, it was a highly successful year. If you were fortunate to shoot a deer, you were the local community hero.

In time, whitetail deer populations increased, thanks to the eradication of the screwworm fly and its flesh-eating larvae. Eventually, bucks with spike antlers were legal. The first year was the year I shot the buck just described.

Growing up in the country and being around those who loved the outdoors, I was taught while still in diapers how to hunt, fish and respect animals and their habitat. During my growing years, I spent any spare moment in the woods. Alas, there was hardly ever enough time because of chores related to our family’s hog, cattle and chicken business. At night, after work was completed for the day, and after I learned to read, I devoured hunting stories and anything about hunting guns. I had a hard time remembering school’s theories, theorems and the like. But I could quote word for word stories written by O’Connor, Ruark and other outdoor writers of the 1950s and ’60s.

Long before entering Texas A&M University, I knew I did not like school, but also knew that if I wanted to become a professional wildlife biologist, I needed a degree in Wildlife Science. During my years as a professional wildlife biologist/consultant, I wrote a lot of articles and columns as well as books about hunting and guns. I served on staff with many outdoor publications including a stint writing “The Longhunter” column for Sporting Classics. During my long career as a writer, television show host and wildlife management consultant, I hunted big game on six continents, but doing so kept me away from my home place where I had started hunting as a youngster. Always I yearned to return “home” to hunt whitetails. All I had learned about wildlife, hunting and even life I could relate to hunting those “back home whitetails of my youth.” Those days had served me dutifully and well.

It has been said “You cannot truly ever go home again.” Fairly recently I decided to prove those words not only lacked substance, but were dead wrong, particularly when it came to hunting whitetails.

After living in southwestern Texas’ famed Brush County for three decades, my wife and I decided to move back to the region of our birth. We built a home a short distance from Texas’ famed “Blue Bell Creamery,” home of arguably the best ice cream in the world. Partly the move was so I could spend time on my property, which my great grandfather had gotten title to in 1876.

With my return “home,” I began my quest to again take a whitetail buck there. Due to the state’s local antler restrictions at the time, a legal buck was one with at least four points on one side with an inside main beam spread equaling or exceeding 13 inches. Although spikes, too, were legal, I decided not to shoot one.

By the time I again got to hunt my property, the leaning oak from which I shot my first whitetail had fallen. Too, my grandfather’s “Roar” was long gone. Maybe that is what was meant by “You cannot truly ever go home again.”

What to do? Build a ground blind and use one of my personal rifles.

I enlisted the help of my oldest grandson, Jake Johnson. We salvaged cedar posts cut by my father, oak boards from cattle-working pens built by my grandfather and tin from a barn built by my great grandfather. Material and work truly were going to be a family affair.

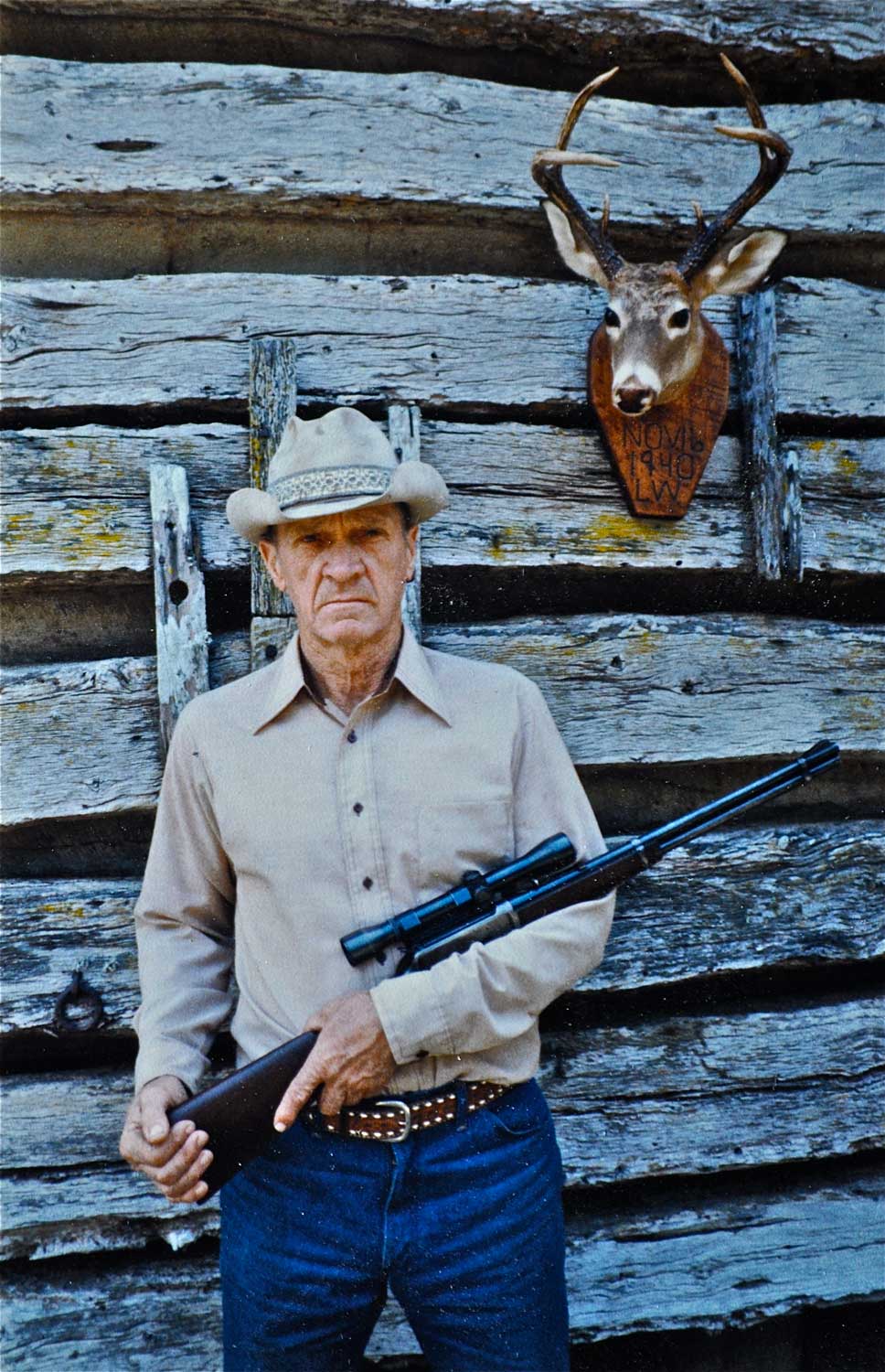

We built the ground blind under the low-hanging limbs of an ancient live oak—the same oak under which I had a ground blind of logs and limbs when I was eight years old. My dad, Lester, had taken his first whitetail nearby in November 1940.

Three heavily used deer trails converged in front of my stand. To sweeten the area and increase buck activity, in early September I made three mock scrapes. Bucks started visiting those mock scrapes the day after I established them.

Area bucks shed their velvet in late August. The region’s rut usually occurs during late October. Archery season opens early October and gun season early November.

I seldom use trail cameras, but I made an exception to determine if there were legal bucks in the area. Third week of October I got a photo of an older, legal buck. He was a 5×4 with a kicker. He appeared to have a 13-inch inside spread, but not much wider.

Opening morning well before daylight, my daughter, Theresa, and I were in the ground blind. The season broke with pleasantly cool temperatures. We hunted until noon but only saw six does, four fawns and a spike.

I had asked Theresa to hunt with me as I wanted to get photos for blogs and articles and film her hunt for an episode of our weekly “A Sportsman’s Life,” which I co-host with Jeff Rice and Luke Clayton on CarbonTV.com. Luke and I also do our weekly “Campfires with Luke and Larry” podcast on Sporting Classics Daily.

Lance Tigrett, Theresa’s husband, hunted another part of the property. The first morning he saw four does and a couple of fawns. We met at noon, heated a pot of stew, compared notes then headed back to our stands. The afternoon passed seeing does and fawns and the second day was a repeat of opening day.

I had to leave for other hunts the next morning and would be gone until Thanksgiving, so Theresa and Lance continued hunting when work schedules allowed. It was early December before I returned.

The first afternoon back “home” arrived with a northerly breeze. Previous weeks, I had been filmed for “A Sportsman’s Life” and “Trijicon’s World of Sports Afield” television shows. My rifle was the same one I had used on previous hunts; a Ruger M77 African 6.5×55 Swedish, topped with a Trijicon Huron variable scope, shooting Hornady’s 140-grain SST Superformance ammo, which is extremely accurate and deadly!

I crawled into my blind, sprayed clothing and gear with TRHP Outdoors’ Scent Guardian then settled in for the evening’s hunt. Sign and spoor indicated deer usually came from the west, then trailed along the backside of a seasonal creek heading toward a brushy wood lot.

Early, I enjoyed the cawing of crows aggravating a hawk, listening the rapid hollow pop-pop-pop hammer-heading of a pileated woodpecker and watching fox squirrels gathering acorns. The sun sank behind tall cedars and the temperature started dropping. A mere sliver of sun remained when deer appeared. I counted six does and four fawns. Three more deer walked out of the dark green cedars, two does and a buck with at least eight points. He made an “airplaning” run at a doe, but she wanted no part of him. I got a good look at his antlers, a 5×4 with a kicker on the four-point side. It was the buck from the trail camera photo!

I waited for him to look directly at me or directly away so I could get a look at his spread. Forward erect ear tip to ear tip spread in our area is generally 13 inches. He turned his head. Inside spread was certainly 13-inches, but not much more. His swelled neck and darkly stained tarsals indicated maturity, at least three if not four years old. Bucks in our area seldom live any older, due to hunting pressure.

Mature, legal, good-looking! I lowered my binos and began watching through my scope as he walked in my direction. I waited, even though I could have easily placed a bullet in his vitals where he was, 250 yards distant.

Suddenly, I was shaking, breathing shallowly and my heart was beating rapidly. It had been 60 years since I had taken my first whitetail on this same property. During those years I had taken many big game species around the world, yet there I was, shaking as if it was my first deer! I loved it!

The buck continued toward me as I took several deep breaths. He stopped 100 yards away as the crosshairs settled on his shoulder. At the shot, the buck kicked high, turned and ran toward the cedars. I bolted in a fresh round, swung with the running buck and gently pulled the trigger. Down he went, sliding forward. I reloaded and immediately got my crosshairs on the downed deer. After 30 long seconds of staying on him just in case he tried to rise, I started walking to where my buck lay.

He indeed was handsome. His rack was smaller by comparison to many other whitetails I have taken from far northern Canada into Mexico, but I could not remember any I was prouder of, except maybe that first one. After 60 years I had returned home and taken a whitetail buck. You can indeed go home again!

That night I called long-time hunting partners to tell my story. Too, I told the story to Theresa and Lance, my other daughter Beth and my wife. After the fifth telling, the four spoke in unison with me as I again told details of my hunt.

It was good to be “home,” taking a buck on my own ground, the land of my ancestors! Today, my buck’s shoulder mount graces the wall of my office. It shares space with considerably bigger antlered bucks as well as the first whitetail buck I shot. His is a short neck mount that looks pretty much like a rat with spike antlers, but frankly, those two “back home bucks” are two of my most prized possessions.