Spain has a long and venerable history of weapon making; these tools led to incredible success during its wars within Europe and afterwards in its quest for global expansion. Many of these triumphs predate those of the French, English and German success. To put our hands around a fine shotgun today, we need to know its roots, so before discussing Spanish shotgun manufacturers and their various cultures and histories, it’s necessary to start in the Basque country — a region encompassing small parts of northern Spain and southeastern France. A proudly independent people, the Basques have maintained their own language, culture, cuisine and lifestyle for more than 10,000 years. Although there is no known historical origin of the Basques, their civilization originated around the same time as the pharaohs of Egypt.

Mining for the quality iron began during the beginning of Roman occupation of the Iberian Peninsula in the mountains of the Basque country, where the Romans discovered high quality deposits of ore, which was primarily used for making swords and other weapons. The Visigoths, Goths and Franks occupied the region for short periods of time throughout the years, but the Basques remained autonomous and were the last group of Southern Europeans to convert to Christianity. In addition, theirs was one of the first societies to abolish feudalism, which was still common in most European monarchies at the time, making them one of the first groups in Europe to recognize the importance of the individual rights of the common man. The Basques were a simple but hardy circle fishermen, sailors and mountain folk and formed hard working and tight communities.

We first find the use of gunpowder during the early 12th century (long before it was common in central Europe), brought to the country during the Arab occupation of the majority of the Iberian Peninsula. The first documentation of gun making in the Basque region dates back to 1480, two years before Christopher Columbus landed in the New World. The first appearances of the word artilleria (artillery) appears in Spain in the 15th century, a word that referred to any type of weapon involving a barrel discharging some kind of projectile using an explosive propellant. It was also around this time that the use of flint lock became extremely popular in firearms, a technology that is believed to have originated with a group of people in the Pyrenees Mountains separating France and Spain, the Miquelitos (or Miquelet in French).

Indeed, the Basque people have contributed more to modern history than many realize: during the 1500s, Juan Sebastian el Cano (a Basque) become the first human to circumnavigate the globe. El Cano was Magellan’s navigator and completed the historic journey after Magellan died in the Philippines.

Fast forward to the 1800s, when the Basques and Spanish begin to take the same fine steel used for centuries in sword making and using it to craft firearms. The demand for this choice steel expanded across Western Europe into France, Italy and Germany, valued especially its use in making the high-quality firearm barrels. The locks (or loading and firing mechanisms) were developed and patented in these other countries, but the coveted barrels came from Spain, particularly the Basque country.

Basque gun making truly took off after the Peninsular War (part of the Napoleonic Wars): Napoleon was attempting to invade Spain and dethrone Charles IV, so the British and Portuguese aligned with the Spaniards in an effort to prevent this. Countless Spanish armaments were raided during these wars and many important and historical Spanish weapons are now lost.

This is when the Spanish and English gun making relationship begins: The English soldiers would take back Spanish made gun barrels to England because of the high quality and the English would bring their gun making technology back to improve on Spanish made firearms.

In 19th century Europe, shotguns were used chiefly for sporting or hunting. The Basque gun making industry became incredibly successful very quickly during this time, but it was not to last. The Basques were very good at manufacturing, but not so good at the other aspect of running a business — marketing, sales, finances, etc. We also see a lot of forgery of Spanish high-end Basque steel appear during this time.

The majority of the remaining factories are located in Eibar, a small industrial town surrounded by green hillsides. Because of the sloped landscape the factories are built on, expansion is limited. The gun making industry and its associated issues are part of daily life in the town, and discussions about gun bans, embargoes, demand and such topics are commonplace.

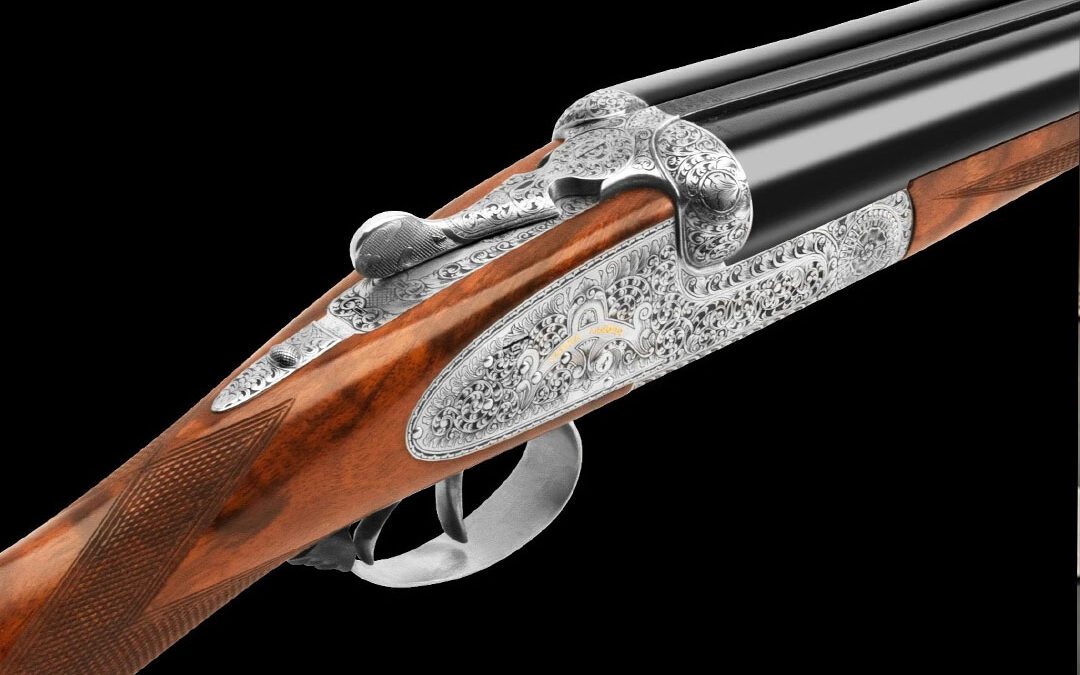

One of the best gun makers in the world was Joseph Manton, active in 19th-century England. His is one the first of many on the list of storied gun manufacturers we know today, alongside names like Boss, Purdey, Lancaster and Greene. These manufacturers set themselves apart by refining their products with ornate engravings, oil finishes on the wood stocks and darkening the barrels.

In 1851, Joseph Lang saw an invention at the London Exhibition by French gunsmith Casimir Lefechaux that used a breechloading pin-fired cartridge — the beginning of center fire cartridges, and shotguns and fowling took off like a bullet (pun intended) with the advent of hammerless guns. London and Bilbao (small city in the Basque country) solidified their banking hub relationship and so this makes the English/Basque trade stronger, increasing the demand for Spanish-made barrels for use by English gunsmiths.

During the peak of the Industrial Revolution, the English are incredibly innovative due to the popular demand of shotgunning. The following inventions come about and of course are introduced to the Spanish gun makers. The Holland and Holland actions in the lock, Purdey’s bolting system, breechloaders, internal hammers, safeties, box locks, sidelocks, ejectors and self- openers.

Significantly, the English made a distinction between the lock, stock and barrels of the shotgun in an effort to standardize these components, making it easier to source different parts outside of England. The Basques follow this same system.

The problem with the Basque gun making industry was that it did not create a legacy among its manufacturers: many times, apprentices would learn the craft for the purpose of striking out on their own. In addition, wars, looting and other turmoil contributed to the Basque gunsmiths’ lack of international success compared to makers like the Holland & Hollands and the Purdeys. The notable exception is Victor Sarasqueta, the royal purveyor of shotguns to the crown during the reign of King Alfonso XIII. An avid shooter and hunter along with the rest of his court, pigeon shooting and grouse moor drives became his greatest passions, and Victor Sarasqueta was tasked with supplying the tools of the trade.

As we move into the late 19th and early 20th century, we see shooting become incredibly popular, especially among the elite (the common folk had always needed reliable firearms to hunt their food). However, troubles were not far off: the 1930s, the Spanish Civil War saw the Basques separatists fighting for their independence from the Spanish crown, but they were no match for the Spanish Republican army and Francisco Franco. After the war, Franco set about systematically eradicating the Basque culture all together. Under his command, the Spanish Republican Army bombed railroad lines, factories and other industry centers in the region. An estimated 200,000 Basques were killed during this conflict, effectively shutting down the tradition of gun making in the Basque country.

During World War II, Spain was neutral and had been blockaded from selling any guns to America. Franco and the wealthy Spaniards start wing shooting again during the 1950s. Due to a resurgence AYA overtakes Sarasqueta as the largest shotgun manufacturer in Spain, still making the same side by sides with box lock and sidelock systems brought about in the early 20th century. These shotguns were mostly made for wing shooting (ie, pigeon shooting, drives and over pointing dogs), not for clay shooting.

This essay was first published in the Charleston Mercury Magazine of Feb. 2024.