Nash Buckingham (1880-1971) was, in his day and still now, one of the most renowned and best-loved outdoor writers to ever ply the trade.

The Limb Dodger was overdue. Concern mounted, and talk had already turned to possible causes of why the train had not bumped and jostled into Evansville on its run from Memphis. The weather was blustery and cold but not particularly threatening. No reports had come of a bridge out in Desoto or Tunica counties.

Mallards rank high on the list of favored waterfowl. They are striking in appearance and are splendid on the table.

My Buck was on this train. Horace had acquired a peculiar demeanor early in the day, and everyone recognized its definitive qualities. It was protective and anticipatory, and it caused Horace to mutter to himself and move about in a world where nothing save his own thoughts and preparations existed. This condition was unique to the arrival of his waterfowling confrere. When that distant gaze captured Horace, learned observers gave him total liberty in the matter. Horace had taken the best two mules and the newest wagon to Evansville Station to bring Mr. Buck back to Beaver Dam.

Someone spoke. It was the familiar voice of an acquaintance, but in that flicker of time between dormancy and consciousness, that voice was alien, ill placed. It served, however, to set aside reverie and initiate reality.

There was no Limb Dodger. Mr. Buck was not on his way. Horace had not hitched the team and rattled off toward Evansville. These objects and people and their inextricable connectedness had been an exercise of the imagination, a function of disturbed sleep. What unfolded in real-time vision outside the eyes was not the same as that seen on the inside. Beaver Dam spread before me.

No longer napping and unable to fault dreams, I had to embrace the possibility that this place was, in its realness, more than simply real. Supernatural. Surreal. Like a colossus, cypress trees stood guard over the darkness and water and memories. They seemed to invite but with reservation, pending a respectful and gentle intrusion. And while Horace and Mr. Buck were present earlier only in my phantasmagoria, they were now present in the chilled air and wispy recall of words read. The whurr of Horace’s paddle and the snick of the action on Mr. Buck’s Becker magnum seemed to drift from the Owen Pool blind, at least in my mind.

Nash Buckingham (1880-1971) was, in his day and still now, one of the most renowned and best-loved outdoor writers to ever ply the trade. The author of nine books and hundreds of articles that regularly appeared in an extensive list of prestigious publications, Buckingham arrived early and stayed late in the writing business. His poetic style gave life to any account he penned.

Within a great deal of his written work and on the backs of collected photos of this man, fond mention is made of Beaver Dam, a duck club in northwest Mississippi to which Buckingham went regularly. Organized in 1882, Beaver Dam was the property of the Owens family. Buckingham’s father was one of the hunters who visited the camp early on, and Nash himself got an introduction to it as a youngster.

Buckingham continued to frequent Beaver Dam as an adult. He would ride the Limb Dodger down from Memphis and offload at the nondescript stop of Evansville, just up the road a bit from camp. Some means of transport would be provided for hunters and gear from that point. It was at this camp that Nash made his last duck hunt. That was 1968, and he was 88. A fitting end to a marvelous life, indeed.

Aside from the grand shooting afforded at Beaver Dam, perhaps the camp’s most significant contribution to this master’s career and life were the Millers. Horace and Molly lived there, and the two were much appreciated and respected by Buckingham. Readers find both highlighted often in Buckingham’s work — Horace for his friendship, steadfastness and expertise in the duck waters; Molly for her culinary talents with all manner of wild fowl. Horace, most will recognize, became the protagonist in Nash’s “De Shootinest Gent’man.”

In one of his most famous works, “Great Day in the Morning,” Buckingham recounts with obvious sentiment his attachment to Beaver Dam: “Across dimming cotton fields I saw lights springing up in tenant cabins and winking through low-hanging wood smoke from fall burnings. Eastward, I could just make out the black rampart of the vast Owen cypress brake — thousands of forest monarchs towering just as God grew ‘em….”

Blind makeup. The author’s pale skin and gray beard suggest the need for camo, even while hunting from a secure blind.

And here I stood — in the shadow of Nash Buckingham. I lacked the eloquence of this wondrous gentleman, but I did possess tremendous fascination for the moment. And unlike Mr. Buck, I had no Burt Becker “Bo Whoop” with which I was infinitely familiar. But my own Remington Over/Under had become a trusted companion. I was minus a long-time comrade such as Horace, but I was comfortable with those who shared the experience. Mallard multitudes were not predicted, blackening the sky with their passing, but a scattered few, an occasional rush, would be adequate. The quintessence was Beaver Dam. And it lay at my feet, those same cypresses Buckingham spoke of reaching high and standing sentinel, guarding yet welcoming, shivering in Delta cold. Sunrise would be along directly.

Somewhere about a half-mile off from that launch was a blind. It came into view as a haunting, skeletal apparition that quickly materialized as something far more substantial than it first appeared. Battery-powered lights cut through the mist and allowed our party to step gingerly into assigned slots and store gear. Not long afterward, coffee was brewing in a pot on the gas stove in one end of that blind.

Over there, westward, was the Big River. It was not close, but as the duck or goose flies, not so far away. And although it could in no way be seen from our station, just imagining it was sufficient. The knowledge of its power and control over much of life here gave it a presence even if the river itself were not visible.

Clouds were stubborn. Daylight was slow coming. It struggled to splash some color of dawn on the landscape, but the effort was not well received. Enemies of the light were afield, and had it not been for the inevitability of a new morning, they would have kept darkness in place.

But even before these stalwarts succumbed and gave way, those of us in the blind knew wild fowls were about. A hissing whistle of wings would disrupt the air just above our heads. The mournful quack of a lonesome suzy would serve notice that mallards were somewhere near. The occasional plop of water out there in the slough told any careful listener that ducks were dropping down and beginning to sort out the day’s regimen. In the distance, chattering honks and chuckles came from thousands of geese that were making ready to rise from one spot only to settle at another and rise again to, so it seemed, drift aimlessly about the flat lands with constant conversation and a steady rearranging of their flighty “V’s”.

Finally, it was time — legally. We could begin to do what we purportedly came to do. Hunt ducks. A half dozen or so made a false pass at the decoys. Mallards. They climbed from the circle of open water in front of the blind and bee-lined for the horizon northward. But before they vanished in the dimness of a cloudy morning, they banked, turning back in the direction of Beaver Dam. This time they passed behind us and came into sight again in front and to the left. The parade went once again to the right, north. This time, however, there was a pronounced change in the flight characteristics, in their demeanor. There was a resolve, not that burning, raging charge to reach distant environs.

Shotguns rumbled. A couple of slides on pump guns were coaxed by that shick, shick backward-and-forward movement to remove spent and ready fresh rounds. One autoloader shucked a pair of hulls onto the blind’s floor. My own Over/Under obligingly flipped a single green case up and out. Three drakes, ripples moving away from them in widening circles, lay in the dark waters beneath cypress and beside decoys. A disciplined retriever did her work with finesse.

And then there were two — male and female. They were falling from the low ceiling and dodging cypress boughs by spilling air from first this and then that cupped wing. Orange landing gear half lowered, the hen crumpled to a charge of No. 6 cast from the shotgun held by a friend to my right. The drake quickly took evasive action. But before he became acquainted with adequate altitude, the charge from my modified tube ended the drama.

Buckingham wrote fondly of mallards. These, and other species, were abundant in great numbers during his writing/hunting career.

Again the retriever. She shook water from a chocolate coat as she heaved back onto the platform. I stroked that intelligent head, her inquisitive and gentle eyes watching my every more. It occurred to me that we might do well to learn from such a creature as this one.

Breakfast was announced. It was purely Southern, much like what Molly Miller might have served Buckingham and other Beaver Dam hunters on any given morning. Biscuits, gravy, ham, eggs, grits. And hot coffee. All prepared right there in the blind. We unloaded and exchanged shooting for one of the true pleasures of the South — food!

Ducks continued to give credence and consideration to the decoys from time to time, but we contented ourselves with observation, resigned ourselves to passivity, concluded that God was the giver of another fine morning. And we reflected on Nash Buckingham.

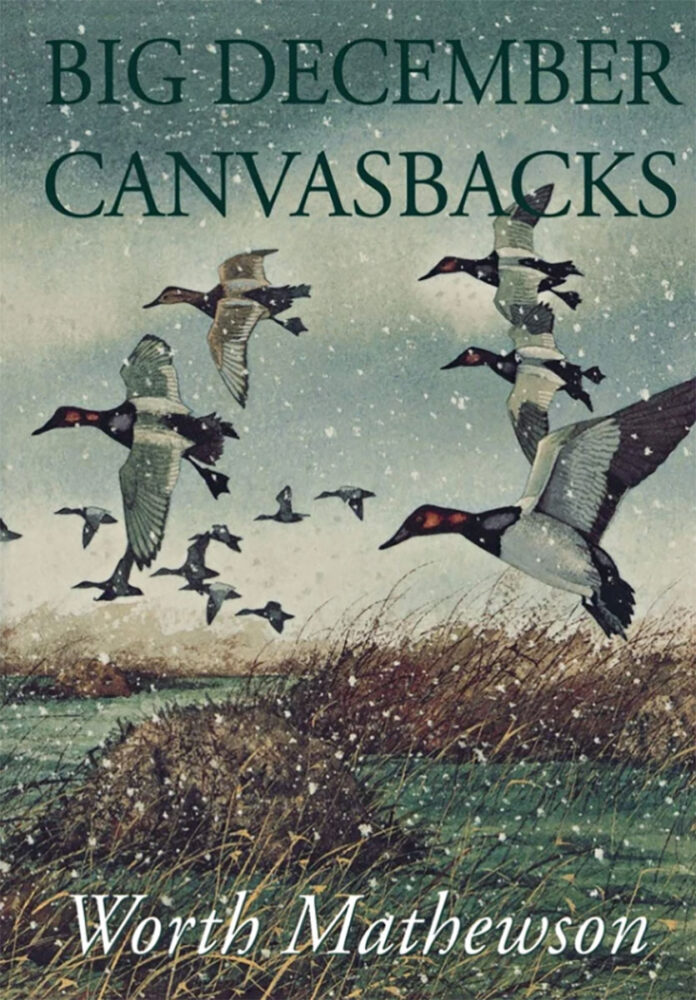

Big December Canvasbacks is a poetic celebration of the beautiful waterfowl of the northwest United States and the captivating places they inhabit. Mathewson, whose writing has regularly appeared in such publications as Field and Stream, has an uncanny ability to take us to the heart of what motivates us to pursue these beautiful animals. The book is lavishly illustrated with line art and will make the perfect gift for any waterfowler. Buy Now

Big December Canvasbacks is a poetic celebration of the beautiful waterfowl of the northwest United States and the captivating places they inhabit. Mathewson, whose writing has regularly appeared in such publications as Field and Stream, has an uncanny ability to take us to the heart of what motivates us to pursue these beautiful animals. The book is lavishly illustrated with line art and will make the perfect gift for any waterfowler. Buy Now