The Making of a Literary Sportsman

Whether you admire him for his prose or the adventurous lifestyle he led, vilify him for his philandering or even pity him for his untimely and ignoble ending, Ernest Hemingway nonetheless remains one of the most influential literary figures and best known sporting icons of the 20th century. He was lauded for his unadorned and minimalistic writing, which broke with the elaborate and rigid style of the Victorian writers that preceded him. He was venerated for his hunting adventures at a time when hunting and shooting were considered part of the American ethos and travel to exotic hunting destinations was exceedingly rare. His exploits in the field appeared in many of the best-known magazines as well as in his short stories and novels. Yet, Ernest was not simply a hunter who wrote about hunting, but rather an insightful writer who deftly wove both the broader context and subliminal implications of the hunt throughout many of his better-known works.

Images of Ernest Hemingway generally call to mind “Papa,” a corpulent, bespectacled, gray-bearded man with a square-toothed grin. Some may see him ensconced at a bar in Key West or fighting black marlin aboard the Pilar off the coast of Cuba or perhaps writing in a cramped Parisian café or even watching the bull fights in Pamplona.

Few people, however, associate him with Michigan and fewer still realize the impact that this place and time had on him as a writer-sportsman. Yet it was in Michigan where he first cast a fly for trout, first learned to shoot, first developed a love of hunting and wild places—passions he would pursue with great ardor throughout the remainder of his life. Here, too, was where he developed his nascent iconic writing style that would one day define and propel his literary career.

Long before wealth and fame, before the vicissitudes of failed marriages, the interruptions of war, and the physical and mental instabilities that would ultimately lead to his demise, there was northern Michigan. His experiences there occurred at a very critical and formative period for Ernest as a writer, as a sportsman and as a man. To fully understand and appreciate Ernest Hemingway the literary sportsman, it is important to contextualize his writings and his evolution as a sportsman with those influences that shaped him during his early years.

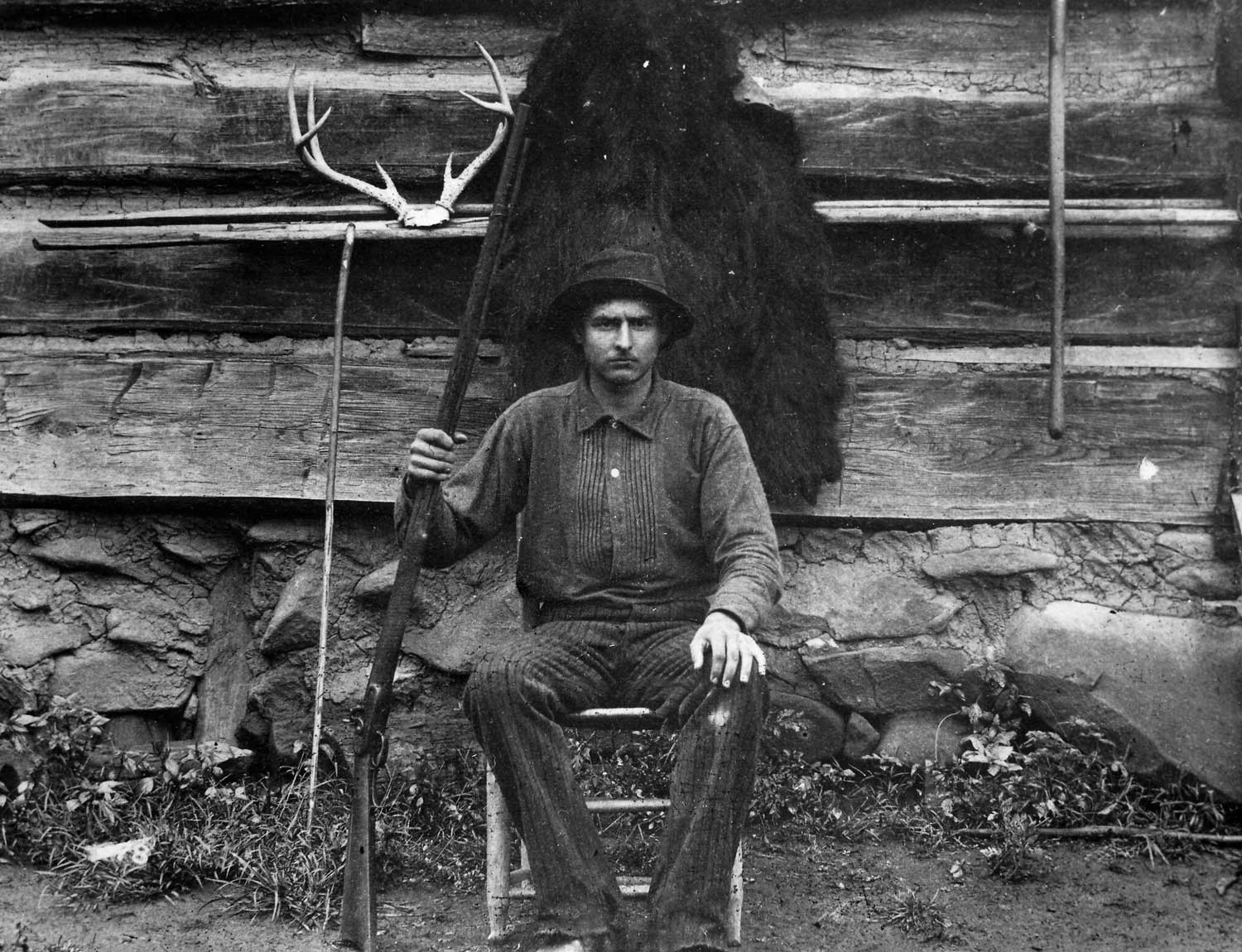

Ernest’s father, Dr. Clarence “Ed” Hemingway, poses with a black bear hide and deer antlers taken while hunting in the Great Smoky Mountains of North Carolina in 1891.

Ernest was only three months old in 1899 when he first traveled from Oak Park, an affluent suburb of Chicago, to the wilds of northern Michigan. Accompanying him were his father, Dr. Clarence “Ed” Hemingway, a general medical practitioner, his mother, Grace, a music teacher and painter and his eldest sister, Marcelline. Seeking respite from the noisy, hot and muggy summers of Chicago, his parents had purchased land on the shore of Walloon Lake in northwestern Michigan and, in 1900, spent $400 to build a single story 30- by 40-foot cottage with a gabled roof and white clapboard siding. The simply appointed cabin was originally named Windermere (later shortened to Windemere), after Lake Windermere in the Lake District of northwest England.

Windemere and its local environs would become the physical and spiritual center for Ernest for the next two decades of his life. He returned there unfailingly each summer from 1900 to 1921, although his time was cut short in the summer 1918, when he shipped out to serve as a Red Cross ambulance driver at the Italian front.

Ernest indelibly preserved his memories of Windemere, the surrounding towns and people of nearby Horton Bay, Bay View, Charlevoix and Petoskey, the local Ojibwe tribe and all the adventures he enjoyed there. His detailed memories of this time became a wellspring that Ernest would return to repeatedly throughout his literary career and from which many of his finest and most respected stories would be based, including: “The End of Something,” “Three Day Blow,” “Up in Michigan,” “Ten Indians,” “The Doctor and the Doctor’s Wife,” “The Battler,” “The Big Two-Hearted River,” “Wedding Day,” among many others.

His first novel, The Torrents of Spring, and many of his Nick Adams stories, all written shortly after moving to Paris in the early 1920s, are semi-autobiographical and based on his meanderings in and around the Petoskey area. References to Michigan also occur in his later works such as The Snows of Kilimanjaro, True at First Light, Islands in the Stream and A Moveable Feast.

Ernest returned to Michigan from the Italian front in 1919 as a decorated lieutenant and still recovering from painful leg wounds caused by an exploding Austrian mortar shell and machinegun fire. He would spend much of that winter toiling away on a borrowed Corona typewriter at a rooming house in Petoskey. It was here where he began his first serious efforts at writing commercial fiction for magazines.

Although his initial writings were met with rejection, he continued to develop and improve upon his use of terse sentence structure, subject dialog, understatement and irony. In addition, the character sketches he compiled at that time about the people of Horton Bay would eventually end up in many of his Nick Adams stories. This early work was among the first to show his promise as a young writer, and it gives us our first inkling that he was about to catch the rising wave of the Modernist writing movement.

By 1920, the family had grown increasingly weary of Ernest’s post-adolescent insolence, his obstinacy, refusal to attend Oberlin College, and his drinking and carousing. Tensions culminated that summer in a letter to Ernest in which Grace banished him from Windemere until he showed respect for his parents and got a job. This break was a seminal event in Ernest’s life and only served to intensify the contempt he had for his mother.

“Best of all he loved the fall. . . the fall with the tawny and grey, the leaves yellow on the cottonwoods, leaves floating on the trout streams and above the hills the high blue windless skies. He loved to shoot, he loved to ride and he loved to fish. Now those are all finished. But the hills remain.”

– Excerpt from a Eulogy to Gene Van Guilder, 1939-Ernest Hemingway.

In 1921, Ernest married his first wife, Hadley Richardson, at the nearby Horton Bay Methodist Church and spent a two-week honeymoon at Windemere. Somewhat enigmatically, it would also be the last time he ever stayed at Windmere or visited Michigan except for a brief overnight stop in 1947 on his way to Sun Valley, Idaho.

When asked later in life if he would ever return to the area, he replied, “No, it’s too civilized now.”

Possibly too, he simply did not want to tarnish his memories of the past by comparing them with the realities of the present.

Like many children of that time, Ernest was introduced to firearms at an early age by his father. His mother, Grace, once said, “Ernest was taught to shoot by Pa when two and one-half and, when four, he handle a pistol.”

This was an era when proficiency with firearms was a much-admired skill, and both hunting and shooting were familiar and predominant elements of the American culture.

Ernest was only 2 when Dr. Hemingway first began taking him on hunts near Windemere and north of Chicago. Grace commented in 1902 that her son, “ . . . loves to play the sportsman. He straps on an old powder flask and shot pouch and half an old musket over his shoulder. He calls different shaped pieces of wood, respectively, ‘my blunderbuss, my shotgun, my rifle, my Winchester, my pistol,’ etc. and delights in shooting imaginary wolves, bears, lions, buffaloes, etc.”

By the time he was 4, Ernest was traveling as far as seven miles by foot on hunting trips with his father and carrying his own gun over his shoulder. With this early tutelage, ready access to firearms and abundant hunting opportunities, it is not surprising that Ernst took to hunting and shooting as he did. Such activities became a regular aspect of his life and, as an adult, he undoubtedly associated those earliest times afield with fond memories of his father. In due time, he would pass that same heritage onto his own children.

Dr. Hemingway was an excellent wingshot and marksman and was a member of the Chicago Sharpshooters Association. He was also an avid hunter, fisherman and naturalist who taught all of his six children, including his daughters, to shoot and be responsible hunters at an early age.

Hunting and shooting were a big part of the summer experience at Windemere. Clarence especially enjoyed shooting clay pigeons, which he had shipped in from Chicago in wooden barrels. Shooting clay targets from a hand trap on the open grassy hill behind the cottage became a Sunday afternoon tradition. Clarnence insisted that no animal should be killed unless it was to be eaten.

One family story describes an incident in the summer of 1913 when Ernest and his friend, Harold Sampson, killed a 14-pound porcupine after it had quilled the neighbor’s dog. It was then that young Ernest was reminded of his father’s edict. The haunches were cooked for hours but they still “tasted like a piece of shoe leather.”

Fourteen-year-old Ernest holds a crow he shot with his father’s lever-action Winchester Model 1887 shotgun.

Not all of Ernest’s hunting and shooting activities were appropriate ones. In the summer of 1915, he illegally killed a great blue heron at the western end of Walloon Lake and then evaded the local game wardens who were trying to arrest him. The incident was later resolved when Ernest turned himself in and paid a $15 fine to the local Boyne City magistrate. Elements of that event would later turn up in his unfinished short story, “The Last Good Country.” He also shot glass insulators off of the electric poles at Horton Bay.

Regardless, shooting and hunting would remain a consistent source of entertainment and escape for Ernest during his adolescence and throughout his entire adulthood, and he would manage to find opportunities to do both, irrespective of where he was living.

Ernest’s paternal grandfather, Anson Hemingway, gave him his first gun, a single-barreled 20-gauge, for his 10th birthday. This was followed some years later by a 22-caliber Marlin lever-action Model 1897 rifle and a 22-caliber Colt Woodsman automatic target pistol. He routinely used these firearms at Walloon Lake and shot on his Oak Park High School rifle club. Ernest also belonged to a trapshooting club.

Ernest acquired many firearms during his lifetime and he had a particular penchant for shotguns and .22-caliber rifles and pistols. For what his taste in firearms reveals about his personality, all the guns he used were generally well built and adequate for the task at hand, but lacking in esthetic adornments such as ornate engraving or highly figured wood. He once remarked that he would “prefer fit and sturdiness and absolute dependability of action to finish.”

Even in later life, when book royalties and movie deals had made him a wealthy man, Ernest still tended to acquire well-made, but relatively plain firearms. What’s more, he was not averse to acquiring used guns if they suited his purpose.

His early firearms, all purchased to be used, were from such well-established companies as Colt, Browning, Marlin and Winchester. Ernest took good care of his firearms. He clearly valued familiarity with his guns and many, like his first Winchester Model 12 shotgun, were worn slick and shiny and bore the scars from decades of hard use in the field.

Much later, he would own numerous firearms, particularly shotguns, from many of the better European makers. However, Ernest’s tastes in firearms remained somewhat utilitarian. In many respects, he viewed his firearms more as a tool as opposed to a form of art, and their acquisition was not considered a means unto themselves.

Although many of the sights familiar to Hemingway more than a century ago have long since vanished, like the church where he married his first wife and the Indian camp, there are still reminders of his youth that he would recognize. The trout streams he fished, such as the Black, Pigeon and Sturgeon, still meander through cool cedar forests; the nearby spring he drank from still bubbles ice cold water throughout the year and ducks still drop in at sunset along the marshy areas of Walloon lake. The Horton Bay General store is still there and his “Windemere” cottage still stands, currently inhabited by his nephew, who inherited it from Ernest’s youngest sister Madelaine.

Northern Michigan provided the literary backdrop for some of Ernest’s most respected short stories and novels. The accounts of his hunting and fishing exploits during that time, and his descriptions of the people and places in the region, would ultimately lead to his receiving the Nobel Prize in literature in 1954 and immortalize him both as one of America’s most influential writers and as a literary sportsman.

Editor’s Note: The author would like to acknowledge Christopher Struble, president of the Michigan Hemingway Society and Valerie Hemingway for their critical evaluation of this article.

This article originally appeared in the 2018 November/December issue of Sporting Classics magazine.