My duck call, The Mallard Toller, is a quality, high-end, custom-made call requiring 10 to 12 hours of labor each. It has many attributes that can’t be found in other calls. It possesses complete tolerance meaning that the sound will not break, squeal, or stop up. It can attain great volume for use on open water and in high winds, yet it also can be blown softly for working birds close in. The sounding device screws into the hard maple barrel rather than using the standard #2 Morris taper. I have never had a reported lost sounding device. The sounding device is made up entirely of inert plastics and is assembled very tightly after being hand tuned. There is no cork or rubber and therefore nothing will deteriorate. Because of this it will hold its tune indefinitely. The barrel is sealed and finished inside and out with a waterclear, high gloss, moisture cure, polyurethane concrete floor finish.

The barrels are made with three types of Maple, those being Birdseye Maple, Maple Burl, and Curly or Tigerstipe Maple. All calls are either personalized or part of a limited edition. Only 100 to 135 calls are made per year enabling them to be very unique and appreciate in value.

My grandfather designed and began making these calls in 1952. I am happy to carry on this family tradition making these calls that are rich in heritage and history, now in our 67th year, and my 25th anniversary! For more information please visit www.heidelbauer.com or call me personally at 605-359-5393. $360.00 value.

From the 2005 Nov/Dec issue of Sporting Classics

A CALLING TRADITION

Story and Photography by Ron Spomer

Like grandfather like grandson, Todd Heidelbauer continues a fifty-year tradition of handcrafting exquisite duck calls.

When he was just a boy, Todd Heidelbauer loved to hunt ducks and geese with this grandfather, Frank. Now in his thirties, he still does.

You might say Todd is a chip off the chip off the old block. He sets his decoys the way his grandpa showed him, calls like his grandpa taught him, and builds duck calls exactly the way his grandpa designed them way back in 1952.

Frankie, as most of his friends knew him, grew up an Iowa farm boy with an abiding passion for and curiosity about the natural world. By age six he was sneaking off to explore glacial wetlands on his father’s farm, learning to imitate the wild ducks that nested there. Gradually Frankie developed into an inveterate tinkerer and craftsman who returned from World War II with two distinguished Flying Crosses and an urge to resume the waterfowl hunting he loved as a boy.

Commercial duck calls of the day didn’t measure up to his high standards, so he built his own, using some of the new acrylic plastics developed during the war. Thereafter he won several national waterfowl calling contests, built calls for friends and donated many to Ducks Unlimited auctions, raising tens of thousands of dollars for wetland habitat restoration and protection.

By the 1960s Heidelbauer was living in South Dakota and working tirelessly to develop Ducks Unlimited chapters statewide. His handmade calls were in big demand around the country. To Dakota waterfowlers, Frankie was Mr. Ducks Unlimited, an infectious salesman, raconteur, conservationist and sportsman in the finest sense of that word.

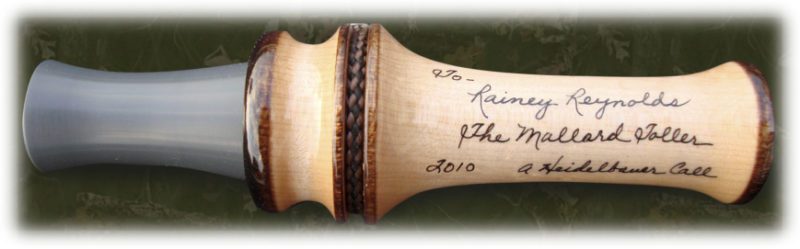

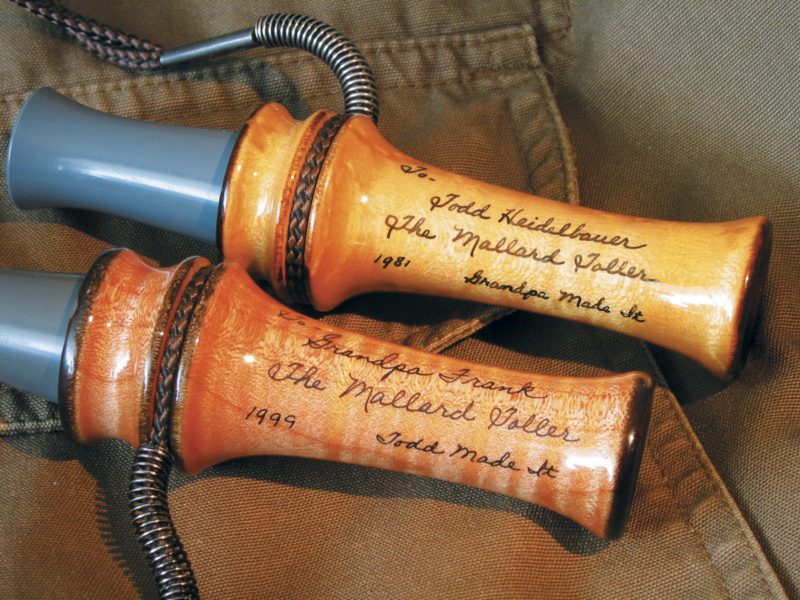

To grandson Todd, a promising student athlete growing up in Minnesota, Frankie was just Grandpa, the clan leader who organized duck hunts and fishing trips and just happened to build duck and goose calls. No big deal – until the day Grandpa presented Todd with a duck call of his own. Inscribed on the bird’s-eye maple barrel were the words: To Todd Heidelbauer. The Mallard Toller. Grandpa made it. 1981.

Here was a keepsake, family heirloom and official initiation into the Heidelbauer clan of hunters. It wasn’t until Todd attended Augustana College in Sioux Falls that he began to hunt regularly with Frankie and realize what an unusual grandfather he was.

“It seemed eve none knew him,” Todd said. “He was written up in magazines, feted at banquets and hailed on the streets. Governors and industry leaders telephoned him.” And fat, greenheaded mallards and white-cheeked Canada geese parachuted out of the sky when he blew his calls beside Dakota wetlands.

Unfortunately, Frankie was also getting old and worn down by years of adult-onset diabetes. In 1994, when Todd was a junior in college, Frankie’s health failed markedly. Weak and stooped from osteoporosis, he was unable to finish building the calls he’d promised folks. I lis two sons, Jeff and Tim, whom he’d hoped might take over his call-making business, were busy with careers and families of their own, but grandson Todd was in town and, like most college kids, short on spending money.

“Grandpa asked if I would come over after classes and help him finish the” calls,” Todd explained. “I thought I could make a few bucks. I never thought it would redirect my life.”

Thus began the younger Heidelbauer’s apprenticeship in Grandpa’s basement workshop, learning the intricacies of custom tools and techniques unique to the construction of a Heidelbauer call. Under the master’s careful guidance, Todd finished the instruments, shipped them to their happy new owners and figured he was done with the call manufacturing business. I lis Grandpa had other ideas.

In the winter of 1995 Frankie’s healdi improved and, with it, his cockeyed optimism. Unwilling to turn anyone down, he agreed to build calls for several people. “He again appealed to me for help,” Todd said, “insisting that this was the last bunch of Heidelbauer calls that would ever be built. It was the end of an era stretching back to 1952. He would bow out of the business and hoped I would help him do it gracefully.” Todd agreed to assist. This time, however, he handled nearly every step of construction while the “chief quality control officer” merely hovered at his elbow.

‘Whenever I got frustrated with an intricate detail that was taking too much time, Grandpa would say ‘Patience is a virtue,’ ” Todd noted. “He was a maddening perfectionist and wouldn’t settle for anything less. Everything had to be done the right way. His way.”

Todd soon became hardened to hearing Frankie tell callers his grandson was “Performing quite well under the long arm of Grandpa’s quality control.” Faint praise for a kid trying to prove himself.

Once again the team finished the calls, Frankie checking the final tuning. Todd graduated with a business degree and took a ‘suit-and-tie job’ as a junior account executive in Sioux Falls. It was to be a short career.

“Over dinner one night I asked Grandpa if he was still getting requests for calls,” Todd recalled. “He said he was but was turning them down. By then I’d kind of developed a liking for building those calls, watching a block of raw maple metamorphose into a sleek call barrel on the lathe. It was satisfying hand work that a desk job couldn’t match. I told Grandpa I’d be willing to build a few calls in the evenings if he wanted to take some orders. You should have seen his face light up! I saw it as a chance to make a little money on the side, but I think Grandpa saw it as continuing a family legacy.”

Grandpa was right.

The rush of orders that followed prompted Todd to form a corporation, Heidelbauer Wildfowl Calls. Five months later he quit his desk job. When he wasn’t in Frankie’s shop building calls, he was in the duck blind blowing them, the bent old man always at his side.

“Grandpa was the duck caller and the more I hunted with him, the better I got. This was critical in learning to tune the calls. Grandpa could tune them to perfection. Heck, mallard was his second language. Hunting with him, listening to him and following his instructions eventually developed my ear. We’d hunt together two to three weeks each season.”

During those years Todd bought a house and began organizing his own basement shop, surreptitiously investing in a new lathe and other tools as he felt the need to assert his own identity. Frankie interpreted Todd’s long absences as rejection. Now that he’d shown the kid the ropes, die old man was superfluous. Only after Todd had his shop running smoothly did he have the confidence to show his mentor what he’d been up to.

“He walked through slowly,” Todd said, “running his hands over die equipment, eying die files and rasps hanging orderly as he’d taught me. I hardly dared breathe, afraid he’d lie offended that I thought I could build a better shop than his. Finally he nodded approval. In fact, he said he was honored that I cared enough about Heidelbauer calls to invest in my own equipment.”

Todd then handed his grandfather a small, white box. Inside, resting on white cotton, was a Heidelbauer call inscribed: To Grandpa. The Mallard Toller. Todd made it.

The next day Frankie presented Todd with all of his special call-making tools and jigs, some of them nearly fifty years old.

Soon thereafter Frankie was forced to move into an assisted living community where nurses could monitor his condition, administer his medications and enjoy his teasing. Todd visited nearly every day and brought each of his finished calls for Frankie’s approval, letting die old hunter scrutinize die fit and finish, asking him for helpful hints and showing him innovative construction techniques.

“I was always afraid he’d chew me out if I changed any step in his procedure, but anytime he saw that a change saved time without compromising quality, he’d welcome it, calling himself’ a ‘dumb old Kraut’ for not having thought of it himself.”

As die old man’s health continued to slide, Todd drove him to his beloved wetlands and carried him into a duck blind warmed by a catalytic heater. Because of poor circulation, Frankie had to be layered with insulated clothing, even with temperatures in the 60s. He could no longer raise a shotgun, but he blew the call Todd had built him and reveled in the sights and sounds of wildfowl, his enthusiasm for nature undiminished.

“He especially loved to watch bluebills crash-landing in the waves from the window of his lakeside cabin,” Todd said, “even if it was too cold for him to go out after them.”

In 2002 Todd took his grandfather out to dinner and reminded him that this was the 50th anniversary of Heidelbauer calls. “He could hardly believe it. He thought it had all come to an end in 1995, and here we were seven years later, still making them. I don’t know if it was just pride or gratitude talking, but that was die year I overheard him tell a caller his grandson’s calls were even better than his own.”

That November Todd again drove Frankie to the family hunting cabin in northeast South Dakota where they were joined by Frank’s two sons and Todd’s brother, Chris, the entire Heidelbauer waterfowling clan.

“Grandpa said he wasn’t feeling strong enough to go to the blind with us, so we left him sitting at the window watching the big Canadas cross the sky and bluebills ride the waves,” Todd said. “When we got back he was feeling worse. We decided to head home, and as we left my grandfather had tears in his eyes.” He died three days later.

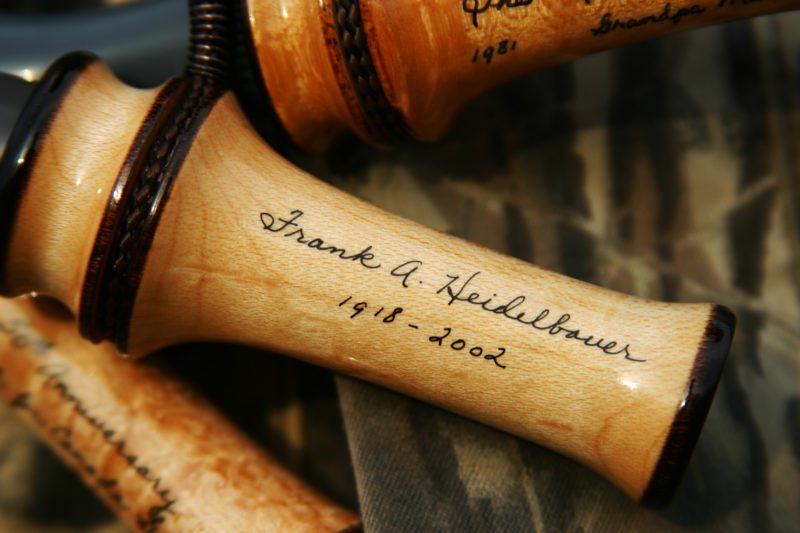

Todd continues building the duck and goose calls his beloved grandfather engineered, and he hunts with three of them around his neck. One is the Mallard Toller his grandpa presented to him when he was just a boy in 1981. The other is a 50th Anniversary Hail Call for Canada geese that he and Frankie made. The third is a special call that makes no sound, yet speaks volumes about an energetic, optimistic farm boy who lived his passion and passed it on to his grandson. Inscribed on the maple barrel are the words: Frank A. Heidelbauer 1918-2002. Inside are Frankie’s ashes.