I had not come here to say good-bye — I already had, and I never would.

The Last eleven miles of road were as I remembered. Even these many years later. Each mile — rutted, washed-out and overhung with cypress and oak — had always seemed to be the price we paid to leave civilization behind. And while much of my youth had been spent on the small oxbow lake that lay ahead, the road had its own set of memories.

The Last eleven miles of road were as I remembered. Even these many years later. Each mile — rutted, washed-out and overhung with cypress and oak — had always seemed to be the price we paid to leave civilization behind. And while much of my youth had been spent on the small oxbow lake that lay ahead, the road had its own set of memories.

The earliest were just the two of us. Although the trip was only 45 miles, we knew that rising rivers, overflowing creeks and bad roads on a good day meant three to five hours to camp. Well before the days of electric winches, it also meant a good shovel, an axe and a come along as essentials for the trip. And yet, the lingering memories are the gentle ones. Always leaving early, often before dawn, I still recall resting my head in his lap as he guided the old Willis Jeep through the early hours.

How many of us still remember that feeling: the touch, the voice, the presence of that man whose love and patience filled the early years of your life? If you still have him in your life, cherish every moment and respect all that he represents. And say while you can those things that your heart knows. He has earned them.

“But he knew all about the birds and flowers,

And he had a way with dogs.

For hint there was beauty in every sky,

And trees were friends, not just logs.”

Nearing the lake, I found myself both anxious and apprehensive. It had been far too long, almost 30 years, and it was not just a trip. There were other reasons —changes in my life, fractures in my spirit — and somehow, I knew that walking back into the past was also, essential to moving forward.

Beaching the bank, on an old trail overgrown with brush and young cypress, I smiled. One of the wonderful things about old oxbow lakes in the South is that they seldom change. The annual floodings, an inability to grow pin e, and very marginal agricultural prospects all join to provide a protection from “progress.” At least for now.

On the surface it was the same. Steep and muddy bank. Brackish, whiskey-colored water, lined with cypress and tupelo. Same noisy quiet. Even in the early afternoon I could hear the whistling wings as wood ducks moved down the lake to the large slough off its southern end.

On the surface it was the same. Steep and muddy bank. Brackish, whiskey-colored water, lined with cypress and tupelo. Same noisy quiet. Even in the early afternoon I could hear the whistling wings as wood ducks moved down the lake to the large slough off its southern end.

I made camp under a giant pin oak, and paused as I recalled all the days spent hunting and fishing that had ended with old men and young boys swapping tales under this same tree. Nearby was a pile of old cypress timbers all that remained of what had once been our cabin.

Tent pitched and the small camp set. The canoe was eased into the water, functional but somehow out of step with the old flat-bottoms we’d built together rough-hewn cypress and hot tar. The 4-weight Sage would work well, but never replace the memory of his old split-bamboo fly rod as it moved quietly through the early morning mist, or glistened from the backdrop of a setting sun.

As I eased along still-familiar shores, and found the big bream on their beds as I’d hoped, my mind drifted back, across years, and moments.

Most were mosaics of falls and hunting seasons that had blurred over the years. Specifics remained — a buck taken here, the day the mallards poured into the slough behind camp, a terrifying night lost in the woods until found by an uncle at 3 in the morning — but right now, raising the bull bream from their beds, gentle blurrings were what I needed.

I smiled as I thought about his constant admonitions about adhering to the established hunting seasons. In his mind we were hunting deer, or duck, or turkey or whatever the regulations defined. From my perspective, we lived at the country end of a gravel road, and most of the meat we had to eat came from the woods. I just went hunting. We both won a few.

“The Old Man now fishes another shore,

And with him in memory you will find

A snubbed nosed, stubbed toed, freckled faced boy,

And the heart of that boy is mine.”

While many of the memories circled around those fall days, I have chosen to return in the spring. The annual floodings that recharge these backwater lakes were over, the oppressive, stagnant days of summer still a couple of months away, and the woods were waking from the slumber of winter. Everything seemed to share that brilliant, pale green that lasts only brief clays.

Most of the time it was just the two of us, often going days without seeing another soul. The fall would bring the deer and duck camps, with family and close friends coming together for the annual rituals, along with a higher level of intensity and anticipation. Fishing, especially in the spring, was a gentler time.

In recent years the majority of my fishing has been on the large reservoirs scattered across our country— vivid reminders of how our fathers’ legacy of flowing rivers has been traded for something labeled progress. Now, as evening approaches and I paddle among the cypress near the shore, I hear again — for the first time in many years — the noise of life. Everywhere. Birds, squirrels, the continuous hum of insects and the sounds we find when the water and the woods meet, and when man is only an occasional intruder.

In recent years the majority of my fishing has been on the large reservoirs scattered across our country— vivid reminders of how our fathers’ legacy of flowing rivers has been traded for something labeled progress. Now, as evening approaches and I paddle among the cypress near the shore, I hear again — for the first time in many years — the noise of life. Everywhere. Birds, squirrels, the continuous hum of insects and the sounds we find when the water and the woods meet, and when man is only an occasional intruder.

Later, as night takes charge, the sounds will change. More will be unknown, and I know even now, in the soft light of evening, that I will probably feel the same vague nervousness as that young boy felt, so many years ago.

I was approaching 20 before I began to understand. He was always easy to love: what young boy wouldn’t worship any man who spent great portions of his time teaching from his vast knowledge of the outdoors? Understanding him, and the framework of his life, took more time, especially for a small country boy from the South.

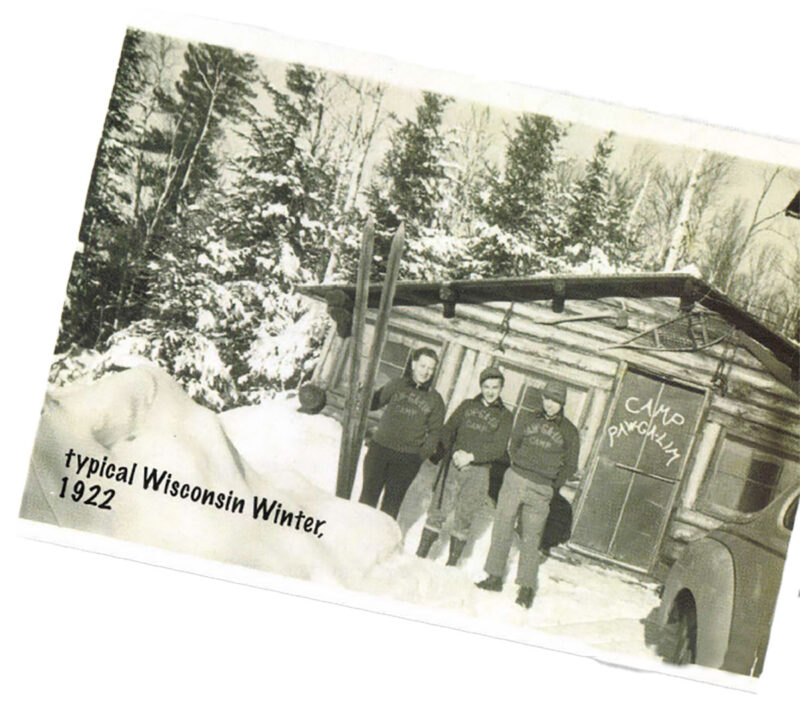

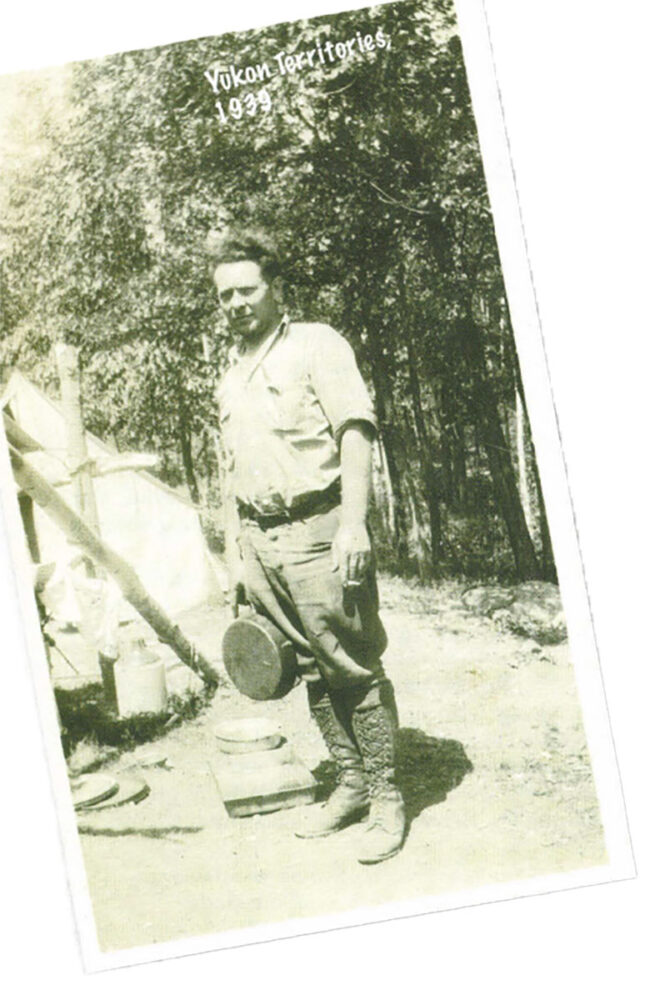

Born in the wilds of northern Wisconsin in1896, he fished, hunted and trapped away his youth in a country still young and wild. After serving in the Navy in the First World War aboard the USS Utah, he disappeared into the wilderness of northern Ontario, and spent the ’20s and ’30s as a trapper and guide. Through his poetry, and the lens of his Argus camera I have followed his trail: his old Winchester Model 94 and Colt Woodsman watching from the wall of my den as I sifted through boxes of black-and-white prints.

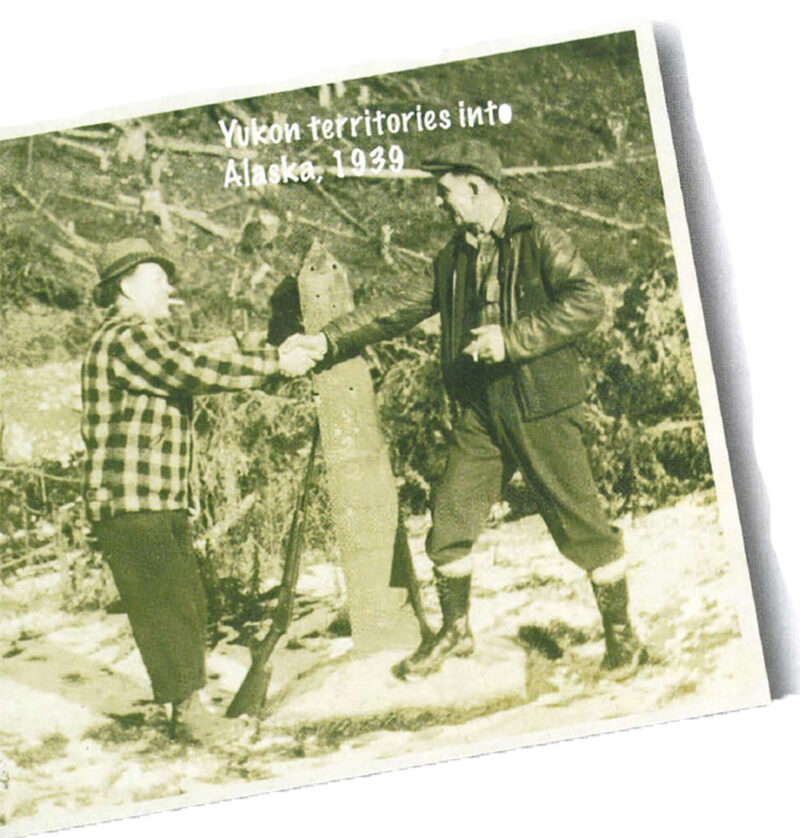

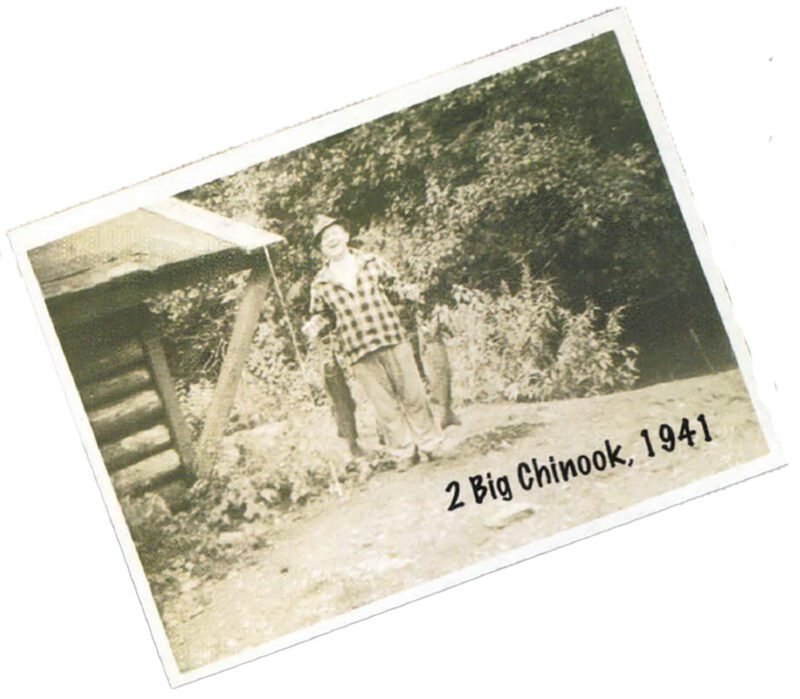

Moving into northwestern Canada in the middle ’30s, he ultimately joined a survey crew laying out the upper stretches of the Alaskan Highway, working as a hunter/cook and filling old Kodak tins with his film. Ending up in Alaska, he spent the Second World War at Dutch Harbor, far out in the Aleutian Islands. Can we even imagine, with our self-imposed priorities, living such an adventure?

Always unassuming — and given to understatement if you could get him to talk of those years at all — I remember asking out a faded picture that showed him standing on wooden skis next to what appeared to be the fallen roof of an old cabin. Yes, he explained, it was the roof of his cabin, far into northern Ontario. Further explanation, kept alive by my prodding, added to the story.

He had left to run his trapline, some 40 miles in length, had been caught in a late spring snowstorm that went on for days, and had “holed up” as he put it, in an abandoned line cabin. Storm over, and the line cabin’s door buried behind feet of snow, he had cut his way through the log roof, skied back along the trapline, and found his cabin similarly buried. Again cutting through the roof, he simply waited for the melt.

He had left to run his trapline, some 40 miles in length, had been caught in a late spring snowstorm that went on for days, and had “holed up” as he put it, in an abandoned line cabin. Storm over, and the line cabin’s door buried behind feet of snow, he had cut his way through the log roof, skied back along the trapline, and found his cabin similarly buried. Again cutting through the roof, he simply waited for the melt.

“What about the trapline?” I remember asking.

“Didn’t find it again until the spring thaw” had been his simple answer.

After the War he headed south, crossed the Mason Dixon for the First time, and helped construct one of the many large munitions facilities our nation scrambled to build as the Cold War began. There, in southern Arkansas, he married the only love of his life and, at the age of 51, he had a son. With his presence and with his poetry he gave me a map for life’s road.

“Yes, a failure perhaps, as we reckon success,

His house built on shifting sands;

But he gave me a love for the wild things,

And a Creed that helps me as a man.”

Swinging the canoe around as the lake began to bend toward one leg of its horseshoe shape, I eased back down the lake toward camp, suddenly aware of the quiet. The occasional whistle of a wood duck going to roost in a swamp just off the lake, and the muted sounds of unseen splashes from the deepening shadows among the cypress — otherwise, only the dip of the paddle to break the silence. It almost always happens. A very special quiet that finishes the day and ushers in the evening, and then gracefully gives way to the night’s own melody.

Camp was a simple thing. Small tent, folding table and my constant companion — an old canvas-backed chair, built low to the ground. The bream, cleaned at the water ‘s edge and covered with cornmeal, along with a quickly sliced potato, hit the grease with the right sizzle. A lantern begrudgingly lit. For all their function I have never really liked lanterns. Lit as evening fades to darkness, they seem to close out all that lies beyond their circle, yet still leaving you feeling centered and exposed to the night’s eyes.

July 1972: I was a young Marine pilot ready to ship out the direct Southeast Asia. Flying into a military base near my hometown, I intended to spend a last weekend with my parents. With many things left unspoken, my father and I left early Saturday for our lake and spent a quiet day fishing its shores. Late spring was in the air, the fishing was good, and most of the conversation was on the surface. There were too many unknowns.

The next day he took me back to base, and watched proudly as I pre-flighted the plane, climbed in and taxied to take-off. Three days later, back in North Carolina, I returned from a training flight to find our executive officer waiting. “Old Man wants to see you, ASAP.”

Entering the Colonel’s office, I was quietly told to call home. Less than an hour later, with a small bag packed, I was headed back to south Arkansas. With a wisdom that I only later understood, I was flying the plane, the Colonel sitting quietly in the back seat. We switched seats when refueling in Mississippi and, breaking all known regulations, the Colonel landed a military fighter at a small municipal airport, shutting down one engine long enough for me to get out.

Entering the Colonel’s office, I was quietly told to call home. Less than an hour later, with a small bag packed, I was headed back to south Arkansas. With a wisdom that I only later understood, I was flying the plane, the Colonel sitting quietly in the back seat. We switched seats when refueling in Mississippi and, breaking all known regulations, the Colonel landed a military fighter at a small municipal airport, shutting down one engine long enough for me to get out.

Less than five hours after his heart attack I was home, and only beginning to struggle with the loss.

The Corps taking care of its own.

Dinner done and the lantern out, I settled back in front of the fire. This day, this evening, was something I had looked forward to, and needed to do, for years. All day I had been aware of the emotions circling just beneath the surface, and the memories. I would touch them for a moment, and then back away. Wanting somehow to turn back to the memories of my youth, and the man who had forever shaped my life, but always finding it painful to dig that deep. I had not come here to say good-bye — I already had, and I never would. And I had not come to find some easier way to remember him, for every memory would forever be filled with both joy and a sense of loss. As the fire settled into the flickering canvas against which I could paint my thoughts, I closed my eyes and listened. And in the sounds of the night, he was there.

“And I see him still in each campfire’s glow,

And the vision is ever a joy.

For the things he knew of the waters and woods,

He wrote on the heart of a boy.”

Author’s Note: The poetry is from one of my father’s unpublished poems.

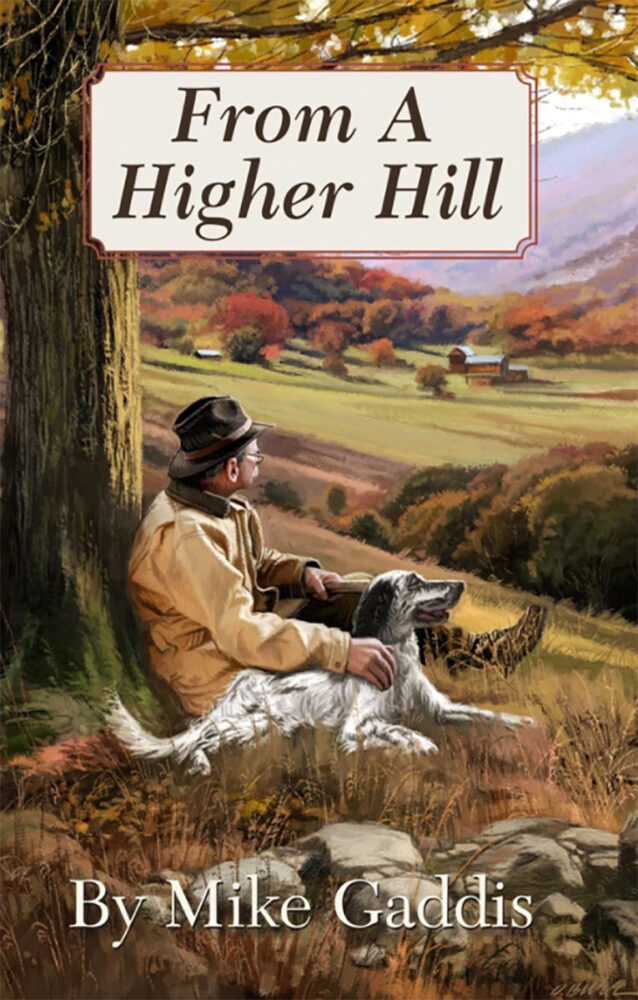

Upon this lofty precipice, one of the most celebrated and insightful sporting authors of our time again reaches beyond himself, this time retrieving sixty-five more episodic explorations of the sporting life, the whole of which transcend contemporary perspective, and ascend to rare and unexcelled poignancy. Buy Now

Upon this lofty precipice, one of the most celebrated and insightful sporting authors of our time again reaches beyond himself, this time retrieving sixty-five more episodic explorations of the sporting life, the whole of which transcend contemporary perspective, and ascend to rare and unexcelled poignancy. Buy Now