I am a confirmed cynic when it comes to supernatural and paranormal malarkey. However…

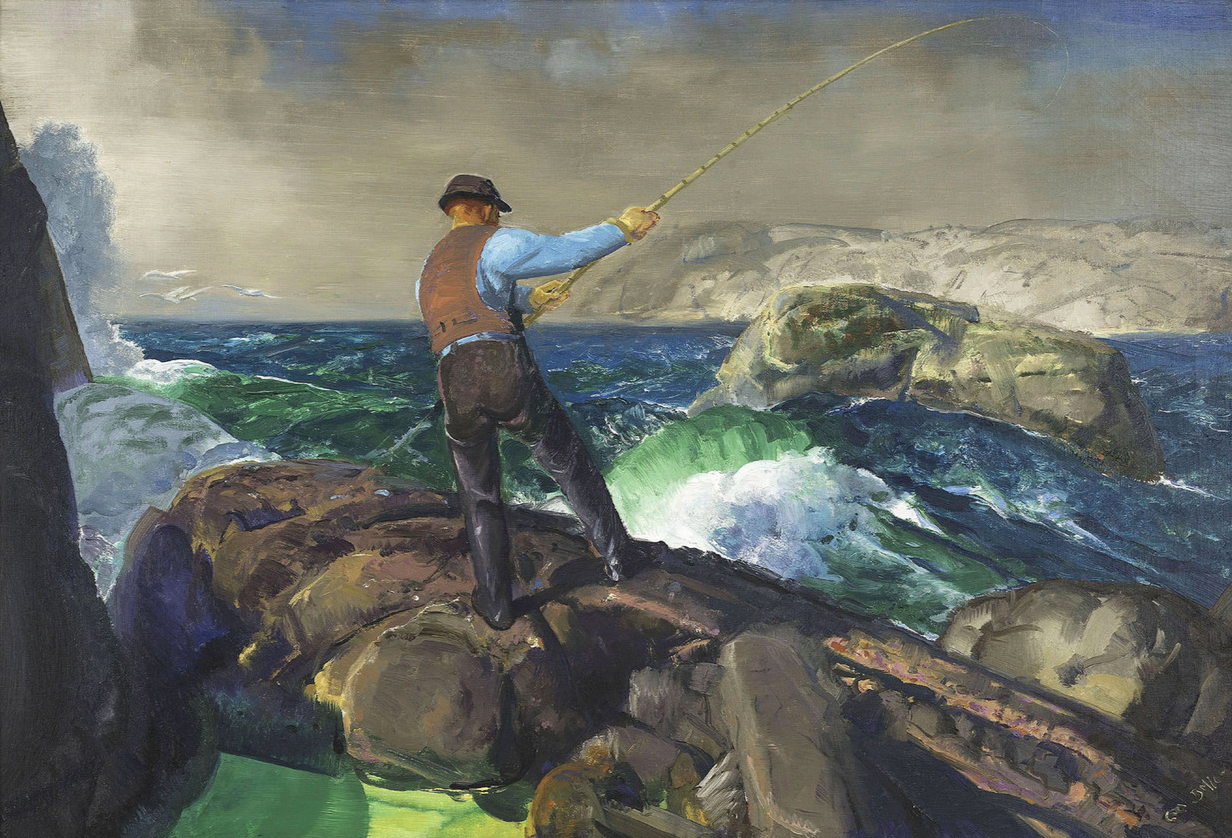

It began innocently enough, as such things often do I suppose. Tom Davis, a contributing editor to this magazine, called me about taking over an article he was unable to do, a piece on the excellent brook trout fishery of the Fox River in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula — the UP as locals call it. Along the way, I could touch on the early life of Nobel Prize-winning novelist Ernest Hemingway, who spent his summers in northern Michigan and, after returning severely wounded from World War I, fished seven days around Seney in the UP.

Many of Hemingway’s first short stories have settings in the Up, and arguably the most famous is “The Big Two-Hearted River, Parts I and II ,” featuring his Nick Adams alter ego. There is a real Big Two-Hearted River farther north of Seney, but it is the consensus of scholars — and was acknowledged by Hemingway in a letter to his father — that he borrowed the more poetic name. The story is actually based on his fishing expedition on the Fox, when he and two friends caught over 200 trout.

Many of Hemingway’s first short stories have settings in the Up, and arguably the most famous is “The Big Two-Hearted River, Parts I and II ,” featuring his Nick Adams alter ego. There is a real Big Two-Hearted River farther north of Seney, but it is the consensus of scholars — and was acknowledged by Hemingway in a letter to his father — that he borrowed the more poetic name. The story is actually based on his fishing expedition on the Fox, when he and two friends caught over 200 trout.

It sounded like a plum assignment. Spend some time wandering around, trying to dig up information about Hemingway and, in the meantime, cast a fly upon a fishery where 18-inch brook trout have been caught and where Hemingway, in his bizarrely enthusiastic epistolatory style wrote in 1919, “Yo heesus an be Guy Mawd Fever I lost one on the Little Fox below an old dam that was the biggest trout I’ve ever seen. I was up in some old timbers and it was a case of horse out. I got about half of him out of wasser and my hook broke at the shank!”

I got my final marching orders in a phone conversation with (then) Sporting Classics editor, Chuck Wechsler, and headed north to Seney in June. As he suggested, I tried to find people who might remember Hemingway. I half expected a billboard outside of town proclaiming this Hemingway Country. No such luck. He returned from WWI with his infamous war injury, was proclaimed a hero and after recuperating in Michigan, pretty much left the area for good.

Now Seney’s just another spot-on Michigan Highway 28, where the speed limit theoretically drops from 55 mph to 40. It’s not much different from other UP towns such as Shingleton and Germfask, Steuben and McMillan: gas stations, a grocery store, a few houses, couple of motels filled with summer tourists. No mention of Hemingway anywhere could I find, not even in the Seney Museum, a dusty one-room building with a stoic attendant in work clothes and an engaging clutter of artifacts from 19th century logging days, when the northern forest was canopied by huge white pines.

The pines and logging days are long gone, and so too, I thought, is Hemingway. I consoled myself with fishing the Fox for the evening, taking a couple of small brook trout, but not tying into any of the behemoths said to inhabit the river. My initial enthusiasm for doing the story was waning, and I returned home the next day.

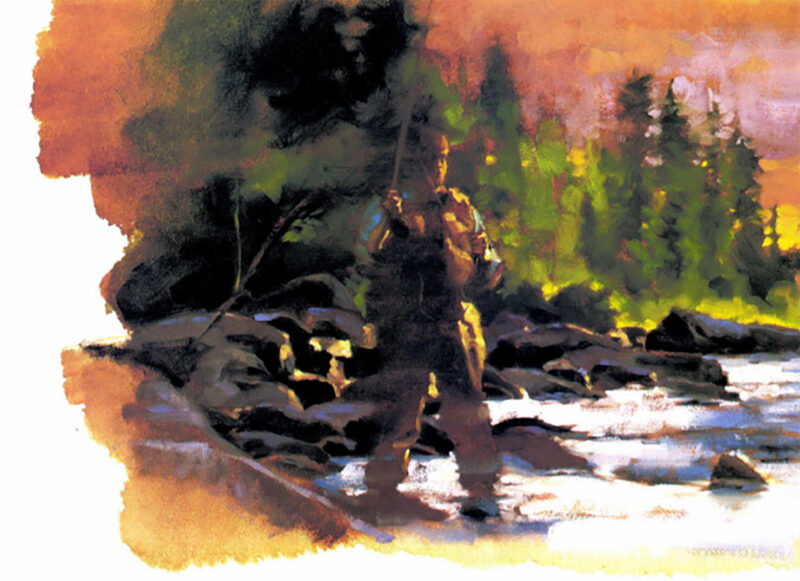

It was July 1st when, mostly on a whim, I decided to give the Fox another try. The first time I had been in Seney, I had fished from the state forest campground north of town. This time I decided to try to reconstruct, as much as possible, Hemingway’s supposed journey. In the story, Nick Adams hikes upstream from the railroad bridge in Seney, with the river on his left. Perhaps he hiked an old logging road. The only road now is on the opposite, west side of the river.

I wanted to drive and walk as far from civilization as I could, hoping to find those big trout Hemingway wrote of. This time I also took my golden retriever, Tess, along for company.

I drove a few miles past the state campground, took a turn-off to my right, then another turn, then a third dirt road that dwindled to a deeply rutted trail overgrown with brush. I parked the Blazer, gathered my gear and shouldered my pack. Tess was excited, as she usually is, by the prospect of getting her nose into some birdy territory.

It was only about a quarter mile walk to the river. I paused to let Tess splash around and drink, then headed upstream, following nothing more than a game trail.

In addition to my pack, I, like Nick Adams, carried my fly-rod, a 7-4 Orvis bamboo. I also brought along an onion sandwich to dunk as part of the ritual — just as Nick Adams does in the story. Hemingway does not go into detail about the sandwich, so I opted for Chicago rye bread with Uncle Phil’s Polish Mustard and a sweet Vidalia onion I had brought back from Georgia.

I found a place to camp, set up the tent and unrolled my sleeping bag. Then I tied Tess to a tree, slipped into my flyweight waders and shoes and headed to the stream. It was late afternoon. Fishing was slow and uneventful. I’ve never found fishing in July very much fun. The sweat was streaming down my face, and the mosquitoes were voracious, even in the middle part of the day. Fortunately, as Hemingway related in a letter to a friend, there were “very few flack Blies” (black flies).

I recalled the part of the story where Nick is ready to fall asleep and strikes a match to torch a mosquito in his canvas tent. I wished I’d had a flame-thrower with me that day.

Then I noticed something, something odd, but which I took little notice of. I was fishing upstream and kept hearing what I was sure was the sound of someone else fishing downstream. At first I thought it might be the sound of a feeder stream, but no stream materialized. Yet each time I stopped, I heard the distinct sound of someone wading toward me. I figured it was probably another Hemingway enthusiast, or perhaps a local angler familiar with the area.

I was sweating profusely, even in my light waders and short-sleeve shirt, so I stopped to sit under a shade tree and contemplate what the hell I could write about for the article. First, I took my onion sandwich out of its plastic bag and dipped it ceremoniously in the stream. I settled down with my back against the tree, sipped a beer I had brought along and ate the onion sandwich. I can’t say I recommend wet onion sandwiches. It tasted like a soggy sponge.

It was then I felt a distinct chill in the air, almost as if there was a current of icy wind blowing. Then, and I swear this is true, I felt something, a kind of presence. It’s hard to put into words, but the only thing I can compare it to was the feeling I had the night my mother died, and I felt her standing at the foot of my bed. That feeling, however, was comforting; this was vaguely threatening.

I have to interject here that I am a confirmed cynic when it comes to supernatural and paranormal malarkey. When people start telling me stories of ghosts and such, and I know they really believe them, well, I try not to scoff openly. My mother raised me to be polite, even to fools.

So I dismissed this feeling a being an overreaction to the heat. It lasted only a few seconds, then everything was normal. I continued to fish upstream a ways, hearing now the sound of someone fishing downstream from me — going away, not coming towards me. I did take a nice brook trout on a grasshopper pattern I had tied myself and took it back to camp for dinner. I had brought along beans and apricots, mirroring at least in part Nick’s meals. I decided to skip spaghetti. Somehow an onion sandwich, beer, beans and apricots seemed dangerous enough.

I was tired, and after an evening walk with the dog, brushed the ticks off her and we turned in. She always sleeps in the tent with me. She may have dog breath, but at least she doesn’t snore like a berserk chainsaw as do most of my other tent-mates.

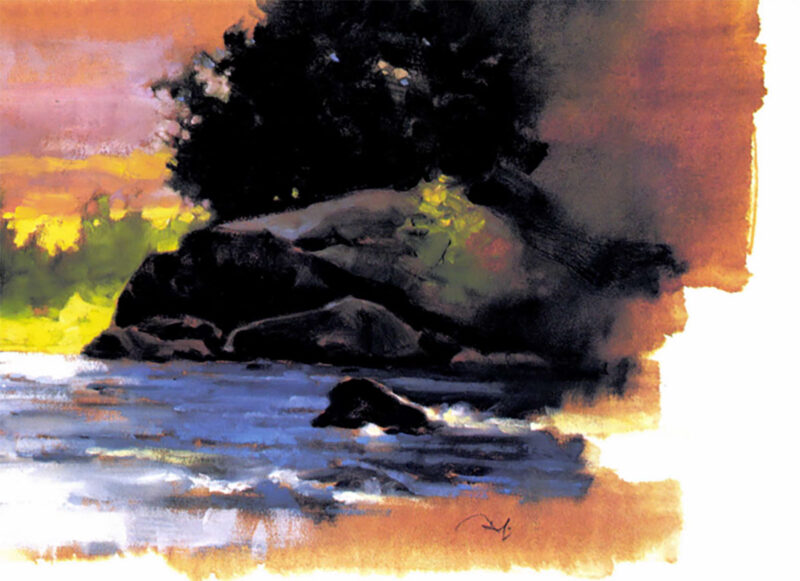

It was after midnight when she started growling. Tess isn’t much of a watch dog. My wife and I joke that if someone broke into our house, Tess would show them where we keep the savings bonds. But something really had her going. I figured it was a skunk or porcupine, though the image of a bear also crossed my mind. I poked my head and the flashlight out but didn’t see anything. She quieted down. An hour later, she started up again. Again, I didn’t see anything. Tess acted like she needed to go out, so I unzipped the screen. She bared her teeth and crept forth. I followed her with the flashlight beam. Then she started wagging her tail and getting all excited, the way she does when we have company over. She went over to a large rock and acted as if she were being petted, then lay down perfectly contented.

I got up and drank the second beer I had hauled along. The beer was warm, but it helped chase the dryness from my mouth. I sat by the embers of my dinner fire. Tess stayed by the rock, looking extraordinarily at peace. I was sure that I could smell coffee brewing somewhere. I don’t drink coffee in the evening because it keeps me awake. But the aroma was distinctive.

It was still very muggy, and heat lightning played on the horizon. Then I felt it again — the chill wind, not just a light breeze, but a sharp, wintry blast. And there was this sense of a presence, a formidable spirit, but hugely sad.

Suddenly Tess barked for all she was worth, then ran to my side by the fire, putting her head on my knee. It’s hard to describe the feelings I had. Fear, awe, confusion. Part of me wanted to pack up and head back to the Blazer and home. Another part wanted to wait, hoping whatever had been in my camp would return and explain itself.

About 3 a.m. Tess and I went back to the tent, and we both slept until dawn. I didn’t feel much like fishing, and I had to get back home by the afternoon. Still, I took my rod and went down to the river. It was then I noticed the imprint of a human foot — barefoot — in the mud along the bank. There were only a couple of prints, but they were recent and all squishy in the mud and made by an adult, not a kid. It dawned on me that in Hemingway’s story, Nick Adams takes off his shoes and wriggles his toes in the water. I chalked it up to coincidence.

I packed up and made the trek back into town, still worried that I had no story and wondering what I would tell Davis and Wechsler.

Later that week, the 7th to be exact, it fell to me to take my teenage daughter, Jessica, shopping for a pair of shoes — not the highlight of my existence on the planet. While she shopped, I rummaged through a couple of used bookstores. In one, I found a copy of Norberto Fuentes’ Ernest Hemingway Rediscovered. I opened it — purely at random — to page 41. And there, staring at me was the date July 2, 1961, the day Hemingway put his fine 12-gauge English double-barrel to his head and took his own life. It was the early morning hours of July 2nd when Tess and I encountered the strange presence on the Fox.

I re-read the Big Two-Hearted stories. Nick made coffee for his evening meal. Nick took off his boots and wriggled his bare feet in the river. Nick fished hoppers downstream. (The sound I had heard while fishing up?) Tess acted like she had found someone who really knew and loved dogs fitting Hemingway exactly.

Now I know there are perfectly natural explanations for all of these goings-on, including heat-exhaustion, an overactive imagination and just plain coincidence. I want to believe at this distance from the event that it did not really happen, that I felt and experienced nothing. But still I wonder. Does the ghost of Hemingway fish the Fox? It was, after all, to northern Michigan that he came to heal after World War I. His fishing adventure on the Fox had obviously been a watershed in his life, both in terms of restoring his spirit and in setting the course for his literary accomplishments.

Hemingway’s last days were a hell, much of his doing. His creative powers had fled, his brain was tormented from concussions, booze and electroshock treatments, his body was wracked by pain and disease. Perhaps, just perhaps, at that horrible moment his shade left the broken body, he returned to haunt the banks of the Fox River, where for one week in 1919 he was so full of life and joy that he wrote in a letter to a friend, “Gad that is great country.”

Hemingway’s last days were a hell, much of his doing. His creative powers had fled, his brain was tormented from concussions, booze and electroshock treatments, his body was wracked by pain and disease. Perhaps, just perhaps, at that horrible moment his shade left the broken body, he returned to haunt the banks of the Fox River, where for one week in 1919 he was so full of life and joy that he wrote in a letter to a friend, “Gad that is great country.”

Hemingway on Fishing is an encompassing, diverse, and fascinating assemblage. From the early Nick Adams stories and the memorable chapters on fishing the Irati River in The Sun Also Rises to such late novels as Islands in the Stream, this collection traces the evolution of a great writer’s passion, the range of his interests, and the sure use he made of fishing, transforming it into the stuff of great literature.

Hemingway on Fishing is an encompassing, diverse, and fascinating assemblage. From the early Nick Adams stories and the memorable chapters on fishing the Irati River in The Sun Also Rises to such late novels as Islands in the Stream, this collection traces the evolution of a great writer’s passion, the range of his interests, and the sure use he made of fishing, transforming it into the stuff of great literature.

From childhood on, Ernest Hemingway was a passionate fisherman. He fished the lakes and creeks near the family’s summer home at Walloon Lake, Michigan, and his first stories and pieces of journalism were often about his favorite sport. Here, collected for the first time in one volume, are all of his great writings about the many kinds of fishing he did—from angling for trout in the rivers of northern Michigan to fishing for marlin in the Gulf Stream. Buy Now