by Joe Coogan

In June 1952, Robert Ruark and his wife, Virginia, arrived in Nairobi, Kenya, to fulfill Rurak’s long-held dream of hunting big game in Africa. He’d nurtured the dream from as far back as he could remember, certainly, back to the days when his grandfather—the “Old Man”—taught him to hunt and shoot.

Ostensibly, Ruark was acting on doctor’s orders to take some time off, and had booked a six-week East African safari with legendary outfitters, Ker & Downey Safaris. Ruark’s pairing with Harry Selby was fortuitous, and yet, occurred purely by chance. Harry admits that, had the company realized how much world-wide attention and publicity the Ruark Safari would generate, the safari almost certainly would have been conducted by either Donald Ker or Syd Downey.

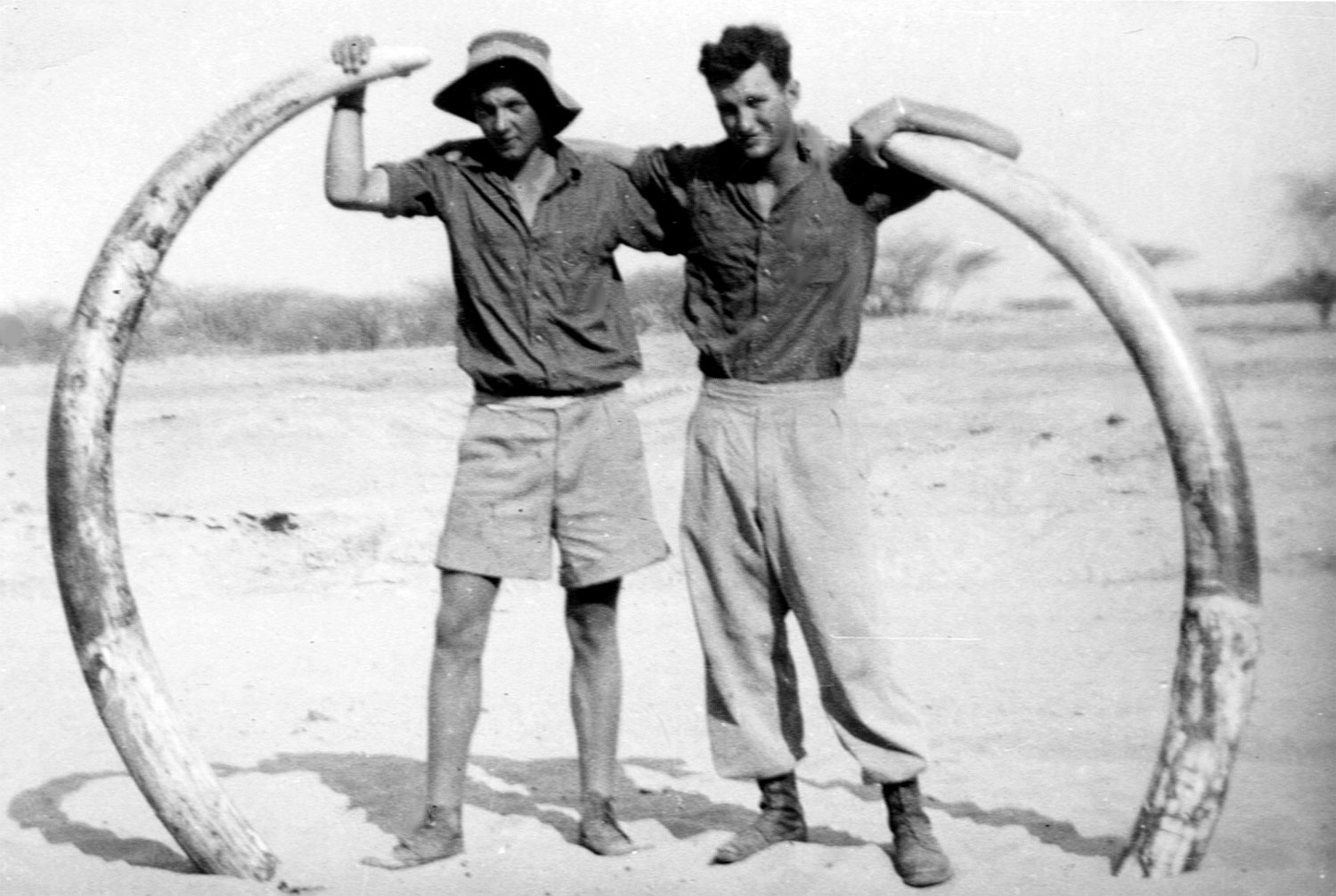

Robert Ruark’s first safari took place in Tanganyika in 1952 with white hunter, Harry Selby (left). Shown here are Selby, gunbearer Kidogo and Ruark with a fine East African eland.

Harry and the Ruarks departed Nairobi the morning after their arrival, right after their custom-tailored safari clothes and boots, made overnight by Ahamed Brothers, were delivered to the hotel. The Ruarks spent the next three days traveling into the wilds of Tanganyika (now called Tanzania). By day they bounced across bush and plains on rough dirt tracks, driving amongst a myriad of wildlife, and camped at night wherever the day’s travel brought them. The Ruarks had plenty of time to get to know Selby and they were impressed by their young white hunter’s capabilities—Harry would turn 27 years old during their safari.

“This ‘brawny child,’” Ruark wrote,

“…was going to run my life for me…

and Virginia after three days was just a little bit in love with him already.”

Ruark soaked up Africa like a sponge and by the end of the safari he was so moved by the African experience that he wrote a book about it called, Horn of the Hunter. Ruark’s story went well beyond the usual hunting exploits, by reflecting his thoughts and feelings about the everyday events of life on safari. Selby featured largely throughout the anecdotal and often humorous tales, making his name familiar in safari circles throughout the world.

In Selby’s Own Words:

How Robert Ruark Booked Me on Safari“I’ve read several versions by various writers describing how Bob Ruark came to hunt with me on his first safari. Most versions are incorrect, and the truth of the matter is rather anticlimactic. Here’s how Bob came to hunt with me: “Frank Bowman, an Australian who had lived in East Africa for many years and who hunted for Ker & Downey Safaris decided to return to Australia. He had recently taken a client on safari, who was the kind of fellow who, when telling about his safari back home, minimized the role of the white hunter and gave the impression that he’d made all the decisions along with his gunbearer, Kidogo. Bob met this chap and asked for advice as to how to arrange a safari. He told Bob, amongst other things, to request the hunter with whom Kidogo, the gunbearer, was then employed. That happened to be me. Bob did this and that is how I happened to take him on safari the first time. So, in fact, Ruark came to hunt with Kidogo, which shows what nonsense is sometimes put out by those who pretend to have done it all by themselves.”

—Harry Selby, Maun, Botswana

After that first safari, Ruark returned to Africa frequently throughout the 1950s, sometimes traveling there two or three times a year. Together, Ruark and Selby even traveled to different countries where Ruark, on magazine assignments, monitored the politics of newly independent nations. He often referred to the chaotic beginnings of independence as the “winds of change sweeping across Africa.”

Growing Up in Kenya

Harry Selby’s family carved their homestead out of 40,000 acres of wilderness with game-filled plains in the shadow of Mt. Kenya, Africa’s second highest mountain. Harry’s earliest recollections were of conversations when his father and uncles discussed the troublesome herds of game, particularly buffalo and zebra, that competed with their cattle for grazing and even the occasional lion and leopard that prowled the game-rich farm.

Harry learned to stalk and shoot small game from the age of eight, progressing to larger game as he got older. He became familiar with dangerous game by learning to avoid it on the heavily-forested slopes of Mount Kenya where elephant, buffalo and rhino were common. When Harry and the young natives he hunted with came upon any of these animals in thick bush, their survival often depended on outwitting or out-dodging the ill-tempered brutes.

Harry hunted his first elephant with an older cousin when he was 14 years old. They each bought an elephant license and traveled in an old 3-ton truck to the Northern Frontier District (NFD) of Kenya. It was, and still is, considered some of the wildest and most remote country of East Africa and would become one of Harry’s favorite hunting grounds.

Harry bought a 425 Westley Richards rifle for the hunt, which pushed a 400-grain bullet at about 2,300 fps. The rifle sported a 28-inch barrel, long for a heavy-caliber rifle, but proved to be very accurate. Harry’s cousin carried a 450 NE double rifle. They camped at a place near water where elephants had dug in a dry riverbed. They parked the big truck in camp and did all their hunting on foot.

“One day we tracked eight bulls for quite a distance into the back country,” Harry recalled. “When we climbed up on a rocky outcrop for a look around, we found all eight bulls spread out in front of us—the magnificent sight of those big bulls is one I’ve never forgotten. Three of those bulls carried tusks that weighed well over a hundred pounds apiece.

“My cousin, who had done some amount of elephant hunting, told me that we should both shoot at the same elephant. We whacked the big one and watched the others run away. The one we knocked down was a superb elephant with tusks of 135 pounds aside. Two of the others were also hundred pounders. We looked for their tracks for the rest of our time there but never ever found them again. In hindsight, we could have easily taken the two biggest.”

During the war years, Harry, who was too young to serve in the military, spent much of his spare time hunting with native trackers to supply meat for the wartime effort. He perfected his gun handling and sharpened his shooting eye during that time with an old blue-worn, silver-looking 303 British military rifle with iron sights.

Safari Beginnings

When the war ended in 1945, Harry took on a new job that would change the direction of his life. During the Ethiopian campaign, Harry’s brother-in-law, Peter Pedersen, a British army officer, became friendly with J.F. Manley, a fellow officer in his regiment. During peacetime, Manley managed a top-rated safari outfitting company called African Guides whose roster of renowned white hunters included Philip Percival, Alan Black, Pat Ayre, Tom Murray-Smith and Bror Blixon. On Harry’s behalf, Pederson asked Manley if he could use another hand on safari, to which, Manley responded, “We can always use a good hand who isn’t afraid of work.”

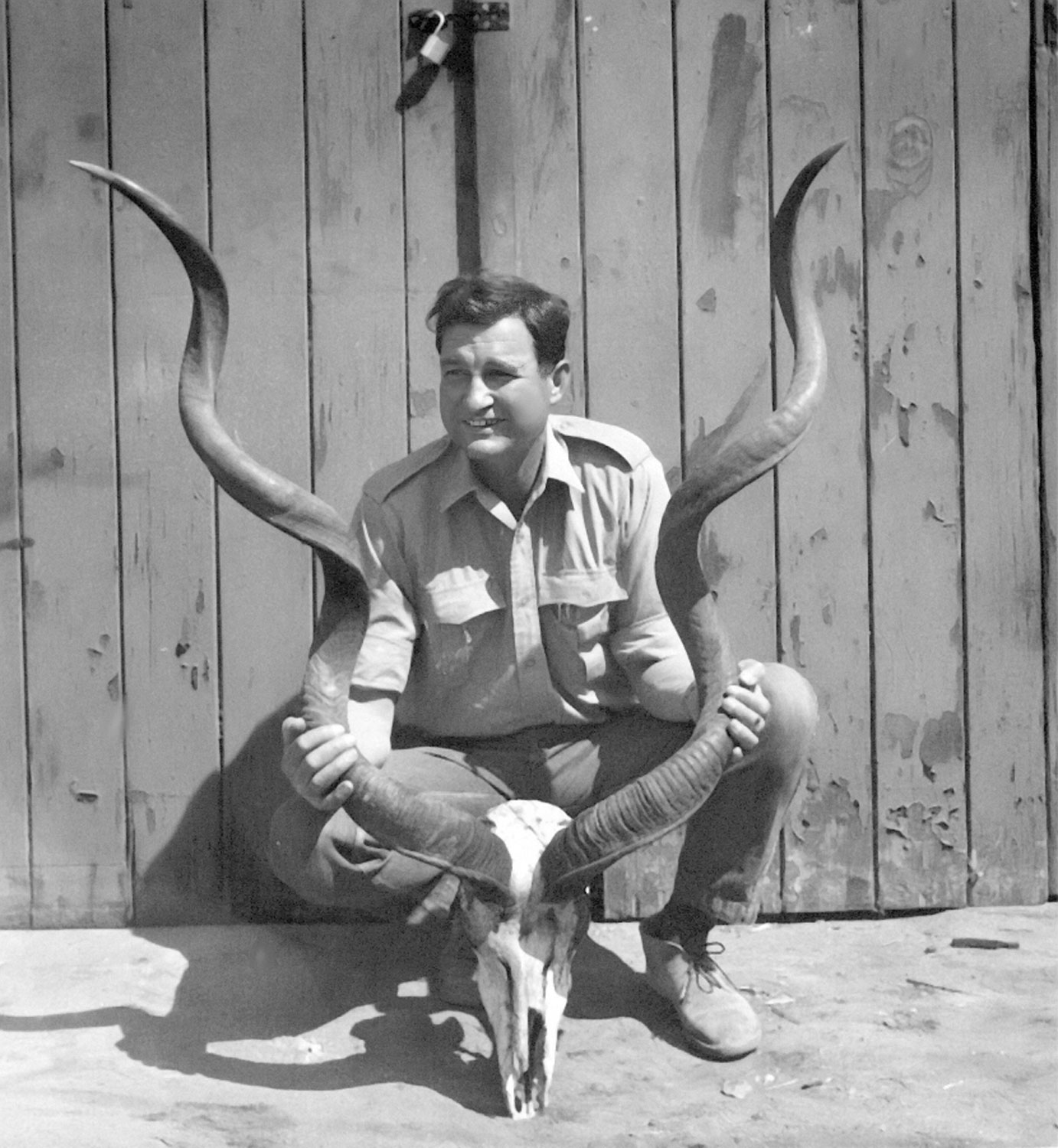

Harry Selby holds highly-prized greater kudu horns, the primary goal of both Hemingway and Ruark on their respective safaris taking place in Tanganyika 20 years apart.

In October that year, Philip Percival was preparing for his first safari after the war. Percival, considered the dean of East African professional hunters, had a rich history that included being a part of the Roosevelt safari in 1909 and leading Hemingway’s Green Hills of Africa safari in 1933/34. It was widely known that Percival hated vehicles and needed someone with mechanical knowledge to help maintain his safari car and equipment while on safari.

“Clients tend to see their white hunter as a father…. He looms in their imagination. They are proud of him, and should he happen to visit them at their home in the northern hemisphere they will make sure that as many of their friends as possible meet him and see for themselves his invincibility.”

—John Hemingway No Man’s Land, 1983

Based on Pedersen’s recommendation, Percival agreed to take on 20-year-old Selby as his field mechanic. Good with his hands, Harry was not only a capable mechanic, but also took pride in his gunsmithing abilities. Percival quickly recognized Harry’s talents extended well beyond his mechanical abilities. His personable nature, considerable big-game experience and skilled gun handling made his transition to becoming a white hunter imminent.

A gunbearer of Percival’s who noticed that Harry always seemed to be busy, or on the move, christened him with the Swahili nickname, “Haraka,” meaning “man in a hurry”—the name stuck with him ever since. Harry’s reputation was well-established by the age of 25, providing him with a steady stream of safari clientele who sometimes booked five years in advance in order to hunt with him.

As Kenya neared independence in the early 1960s, Harry began hearing about a British protectorate located in southern Africa called Bechuanaland, later to become Botswana. Sketchy reports indicated an abundance of game existed there. With Kenya’s future uncertain and hunting pressures increasing, Harry decided to explore the possibilities of new hunting grounds in Bechuanaland.

The country was still a British Protectorate when Harry first traveled there, only gaining its independence in 1966. Most of the southern two-thirds of the country was made up of Kalahari Desert while the northern-third was dominated by mopane scrubland, seasonal waterholes and tsetse flies. Between these two vastly different areas spread a 6,000-square-mile delta system called the Okavango where gin-clear waters flowed along palm-fringed islands and over grassy flood plains to seasonally attract spectacular concentrations of big-game.

Harry spent more than 20 hours in a Piper Super Cub surveying the Okavango and the northern areas from the air and found Bechuanaland to be an incredible, unspoiled country that seemingly time forgot. The country was sparsely populated with little infrastructure—there were few if any roads or tracks, and no communications existed other than a meager telegram network and erratic postal service.

“The fact that the country was crawling with an amazing variety of game species made all the inconveniences seem minor,” Harry recollected. “It was like suddenly arriving on a new planet.”

Harry, together with his family, relocated to the small village of Maun, located on the southern edge of the Okavango Delta. As the manager of the new Botswana safari operation, Harry was awarded a directorship in the company, which was renamed, Ker, Downey & Selby (KDS) Safaris.

Harry’s children, Mark and Gail, would also grow up in the shade of acacia trees and within the sound of roaring lions. Gail, like her father, enjoyed hunting, and with Harry by her side she collected a bull elephant with 50-pound tusks at the age of 14. She used a 275 Rigby rifle originally belonging to the legendary elephant hunter “Karamoja” Bell. The historic Rigby had been bought from Bell’s estate and given to her brother, Mark, by his godfather, Robert Ruark.

Mark, who took his first head of game with the Rigby rifle at the age of eight, hunted his first buffalo at the age of 12, his first elephant at 14, and earned a Botswana professional hunter’s license by the age of 18. Mark worked for several notable Botswana safari companies, including Ker, Downey & Selby (KDS) Safaris, Safari South and Hunters Africa throughout the 1970s and ’80s. For the final 15 years of his career, Mark returned to his roots in East Africa, hunting in Tanzania for Tanzania Game Trackers (TGT) Safaris. In 2008, Mark hung up his rifles and returned to Maun to pursue other endeavors that brought into play his creative talents and capabilities. Sadly, Mark passed away in February 2017.

Mr. Selby, I Presume!

My opportunity to meet Harry Selby happened in December 1972. My family had lived in Kenya for the previous six years and during that time my father and I were able to hunt Kenya’s big game as Kenya residents. I recently had finished college and was hoping to find a safari job, if only for a year or two. All indications were that hunting, as we knew it in East Africa, was nearing its final days owing to increased poaching, habitat loss due to expanding numbers of people and a world opinion that legal, managed hunting was bad for wildlife.

Call it fate, or good fortune, but I just happened to be in Nairobi at the same time Harry Selby flew in from Botswana to attend the annual Ker, Downey & Selby (KDS) Safaris directors meeting. Senior KDS professional hunter, Bill Ryan, whom my father and I had met in the bush, knew I was interested in finding safari work and had invited me to the offices in order to introduce me to Harry. Although, Kenya’s hunting future seemed bleak, Bill thought there were better prospects in Botswana where Selby headed KDS’s operations.

Harry walked into the KDS offices the morning we met, to be rushed by a gang of people wishing to have a word with him. Bill was persistent in pushing through the throng to grab Harry’s attention. I clearly remember the honor of shaking Harry’s hand in that brief, but fateful meeting that set the wheels in motion for my relocating to Botswana a month later. I was so awestruck by the legendary Selby that, in my mind, working for him would be the equivalent of a garage band opening for the Rolling Stones.

I served a two-year apprenticeship for my Botswana professional hunters license under Harry’s guidance, spending the first season based at Khwai River Lodge. The lodge was the first of its kind in Botswana to cater to photographic safari clients. There I learned new country, became familiar with new and different game species and, most importantly, learned the ropes of conducting safaris.

Whenever there was interest, Harry allowed me to guide bird hunts in the Khwai River area. On one occasion, I took one of Harry’s clients on an afternoon bird shoot prior to Harry’s arrival at the lodge. We enjoyed a productive shoot and, given my hunting interest, the client invited me to join him and Harry for a buffalo hunt. Harry had no objection to the idea and it provided a chance for us to hunt together—I was delighted beyond words.

The back country waterholes were beginning to dry and game was starting to concentrate on permanent water sources along the northern edge of the Okavango Delta. On most mornings, fresh buffalo tracks could be located where herds had drunk during the night and then headed back into the mopane backcountry to feed and rest during the day. If fresh tracks were located early enough, an hour or two of hard walking usually brought you up to the buffalo herd.

Watching Harry coordinate the hunt with his trackers, explain the plans to the client and ready the rifles to begin tracking the buffalo was like watching a maestro conduct an orchestra. He was in complete control and directed every part of the unfolding scenario. His confidence and capability left no doubt that he was in his element—one he knew intimately and, in which, he was completely at home.

One of the gunbearers handed Harry his 416 Rigby rifle and he received it like it was an old and trusted friend. He pulled back the bolt of the Mauser 98 action and then eased a cartridge into the chamber and flicked on the safety. The Kynoch cartridge he chambered was a 410-grain solid. The client also chambered his Remington Model 700 rifle with a 300-grain solid in 375 H&H Magnum before thumbing on the safety.

Harry gripped his rifle’s barrel behind the muzzle and pivoted it effortlessly onto his shoulder, barrel pointing forward. We began walking on top of buffalo tracks in a line, one behind the other—Harry, then his client, then Harry’s No. 1 gunbearer/tracker (not Kidogo), then me and behind me came the second gunbearer/tracker. Everything took place as smoothly as oiled machinery.

In Selby’s Own Words: How I Acquired My .416 Rigby

“When I began my hunting career, like many of my contemporaries, I carried a double rifle. It was a particularly fine rifle by Rigby in 470 NE caliber. Owing to an unfortunate accident in 1949, when a vehicle ran over the barrels of my Rigby and damaged them beyond repair, I needed to find another heavy rifle on short notice to use on my next safari. There were no double rifles for sale in Nairobi at the time, but I was able to locate a Rigby bolt-action rifle in 416 Rigby caliber. It was a unique Rigby in that it was built on a standard commercial Mauser action—not a magnum Mauser action. With no other options, I bought the 416 Rigby for £100 from the Nairobi gun dealer, May & Co.

“Having grown up shooting bolt guns I was familiar with the fit and feel of the Rigby bolt-action rifle. A finely-balanced rifle, the Rigby felt comfortable in my hands and shooting it was not at all unpleasant for me. Although I was left-handed, early on I had adapted to shooting right-handed bolt-action rifles. I was delighted to find the rifle inherently accurate from the first shot and quickly discovered that the 416 Rigby, pushing a 400-grain bullet, was effective out to 300 yards or more when finishing a wounded animal. For close work in thick bush on dangerous game, I found the 416 Rigby to be even more effective. The penetration of a solid 416 bullet through thick skin and heavy bones was impressive, indeed. Furthermore, I really appreciated the magazine capacity, which gave me four cartridges ready and waiting when needed.

“After using the .416 Rigby for two safaris, I never looked back on my rifle preference—I had no intention of returning to a double gun. Even my Wakamba gunbearers developed a great affinity for my 416 Rigby, which they dubbed the ‘Skitini,’ having trouble saying, ‘416.’ So began a lifelong love affair between myself, the 416 caliber, and the Rigby rifle.”

—Harry Selby

Buffalo Hunt

Following buffalo tracks in soft sand for a little more than an hour, the sound of a buffalo grunt up ahead stopped us in our tracks. Harry signaled for everyone to step quietly, which meant avoiding the cornflake-crunch of dry mopane leaves. We did this by using the sides of our shoes to sweep away leaves from where we would step before putting our weight down.

Harry slowed the pace, but continued toward the buffalo sounds, which indicated they were moving along at ease. He checked the wind direction by picking up some sand and sifting it through his fingers. Drifting dust showed a slight breeze was still in our favor.

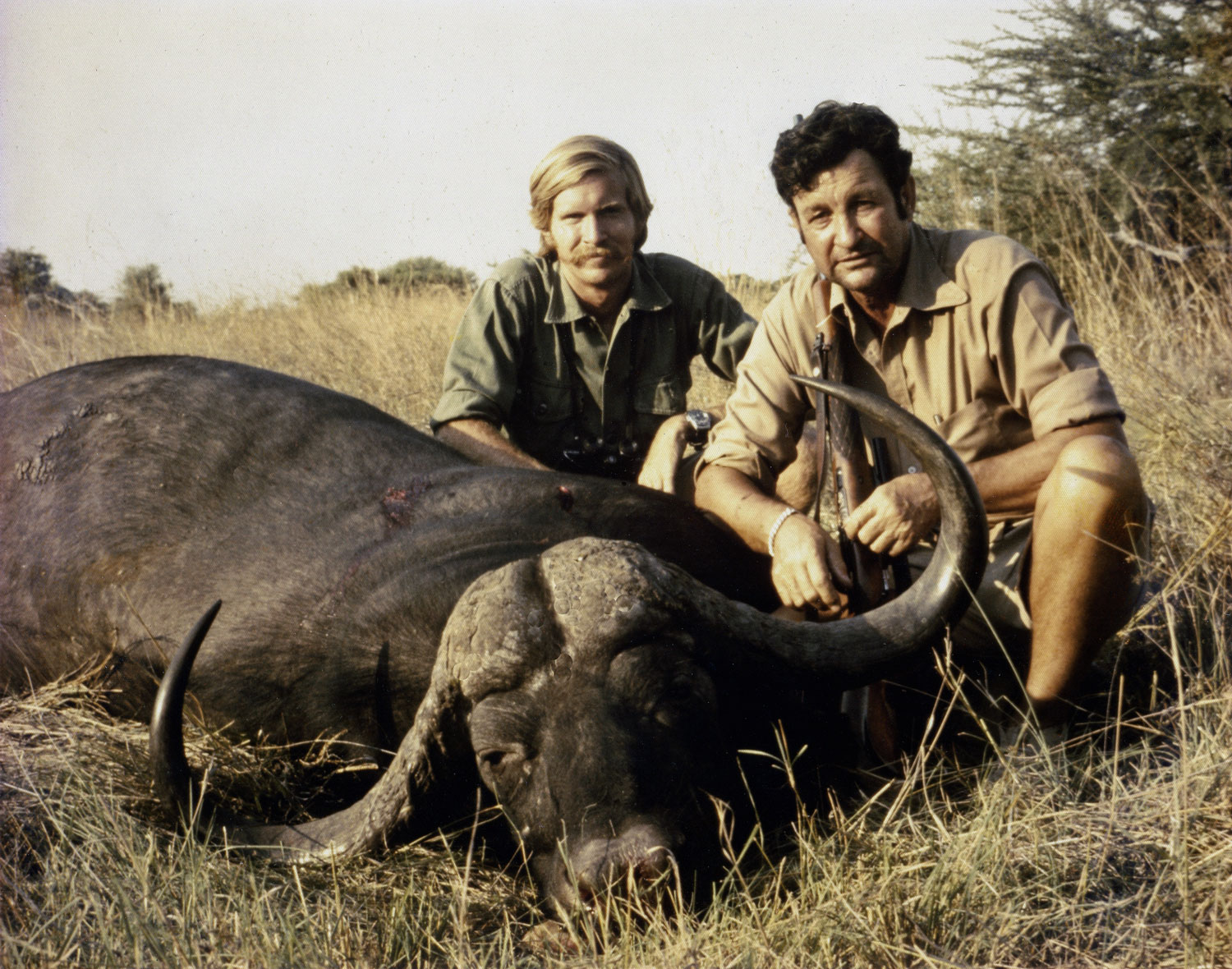

The author and Harry Selby hunted many buffalo together over the years. Here, an Okavango buffalo Selby took in 1975.

We could smell buffalo as we moved closer, a pleasant barnyard aroma that permeated the bush. As we closed with the herd we hunkered down and used cover to conceal our movement. At about 40 yards we were close enough to see the dark shapes treading through the scrub mopane toward some mid-morning shade in which to lay down.

Harry was now fully focused on finding a suitably mature bull for the client. He was able to quickly judge the bulls by body size and bulk. He then looked for weathered and wrinkled faces with a Roman nose and horns extending beyond the ears. A hoped-for feature of mature buffalo horns was the deep down sweep before turning back up to create the formidable hooks.

A buffalo taken by Frank Lyon (left) with Selby and the author in 1995.

For many hunters, a large boss is a looked-for horn feature—the solid mass of horn that covers the top of a bull’s head like a protective helmet. The width of the boss and how close the two horns converge in the middle of the head is a good indicator of the animal’s age and maturity. Cow buffalo have no boss, making it easy to differentiate them from the bulls.

When Harry stopped mid-step he’d spotted a buffalo that had spotted us. As long as we remained absolutely still and the wind held steady the suspicious buffalo would eventually lose interest and rejoin the herd to continue grazing and moving.

Like anyone who is good at their business, Harry wasted no time assessing each buffalo he saw. He looked first with his eyes and then, if needed, looked closer with his 8X binoculars worn on a strap around his neck for quick access. The excitement, stress and effort of creeping amongst the bushes to remain out of sight of the buffalo herd went on for about 30 minutes before Harry spotted the “one.” He stepped sideways to signal the client to come up beside him, shoulder to shoulder.

“See the third bull from the back,” he whispered. “Take him as soon as he’s clear and you feel comfortable!”

The client wasted no time shouldering his rifle and waited for a cow to move out of the way before taking the shot. Harry watched the buffalo’s reaction to the shot and thought the bullet had struck a little high and behind the shoulder to pass through the lungs. The buffalo bucked and kicked his rear legs at the sound of the shot and was immediately enveloped by a thick cloud of dust created by the panicked herd. There was no chance for a second shot.

As we listened to the sounds of the retreating herd charging through the brush, Harry motioned for us to sit down and relax. We waited quietly for the dust and our nerves to settle. Harry also wanted to listen for that distinctive low mourning bellow a buffalo makes when he’s down and dying—no bellow was heard.

When it was time, we stood up and walked to where the buffalo had been standing. Almost immediately, one of the gunbearers found spots of blood on the sand, confirming what Harry believed was a high lung shot. Depending on the severity of lung damage, death might come relatively quickly or, if the damage was not great, and given a buffalo’s tenacity, he might cling to life and be ready for a fight for quite some time. You never knew, so you had to be ready for things to happen suddenly and quickly!

Harry’s gunbearer now moved to the front and followed the tracks easily. Dust lingered in the air making the bushes look eerily like buffalo in the distance. We hadn’t gone far when a dark shape hove into view from behind a bush only 20 yards away. Harry immediately recognized it as the buffalo, but there wasn’t time for Harry to bring the client forward to shoot. At the moment the buffalo launched himself at us Harry had already shouldered his rifle and fired. A quick, well-aimed shot ended the matter with the bull piling up only a few yards away.

“Terribly sorry, but I had to shoot,” Harry offered. “He was awfully close and things were about to happen fast.”

The client was quick to wave away any issues he might have had about Harry’s swift action and was thankful for his participation. The hunt and follow-up was exciting and included all the elements that makes hunting dangerous game so compelling. And best of all we got to see Harry do what he did best.

Harry’s aerial survey of Bechuanaland’s game areas indicated good potential for safaris, confirmed by the excellent quality trophies taken in 1963. Shown here are sable, greater kudu, eland and gemsbok horns held by Karioki, Harry’s Kenyan truck driver.

Thanks for the Memories

Harry Selby spent his life walking among Africa’s biggest game, he slept more nights in tents than in his own bed at home and was constantly expanding his knowledge of the continent, the people and the animals he loved. As my mentor, boss, confidant and friend, Harry Selby handed me an opportunity to live an absolutely incredible way of life. Over the years we hunted together often and shared many campfires while on safari.

While relaxing with a drink around the campfire one evening, I asked Harry what game he liked to hunt the most—it seemed to me, after hearing his stories about big ivory, that it might be elephant. I remember the light of the campfire dancing in his eyes as he smiled and thought about many past hunts.

“Hunting elephants for big ivory still has that special attraction like it did when I first hunted the NFD. But at a young age I rapidly found that I was excited by all kinds of hunting,” Harry declared. “And even today, I think one of the most exciting hunts, and most challenging, is leopard. Although you bait them, it’s always a case of matching wits—yours against his. You do something and the leopard will respond to it and then you have to counter that with something else. It’s as if he is trying to outsmart you.

“And I think that if I had to choose something for real fun, it’s to creep up into a herd of buffalo and have them all around you—your senses are completely alive. That’s probably one of the greatest feelings that big-game provides. But if you want real chilling stuff, it’s tracking lion in thick bush—nothing can compare.”

His answer was thoughtful and clear with no words wasted. It bespoke a respect, even compassion, for the animals that he spent his life hunting. During his life, Harry experienced the situations he described many times, but he never stopped seeking bigger game, finding wilder country or embracing the joys that each day afield brought him.

I last saw Harry August 2017, at his home in Maun overlooking the Thamalakane River. I remember him watching the gentle flow of the river as we reminisced about the good old days we’d shared on safari. Harry enjoyed talking about the good old days and remembering the good times and the funny times. He was pleased to have experienced them when he did and could really have a good laugh remembering the incidents from more than 50 years of safaris that he’d been so fortunate to do.

To most people looking at it from afar, Harry’s life and career was an illustrious, if not glamorous enterprise—it was certainly eventful! But what Harry got to do was experience the best of Africa, at the best of times and with the very best of people. He had no regrets and would not have changed a thing.

On January 20, 2018, John Henry (Harry) Selby died peacefully at his home in Maun, where he’d lived for close to 60 years. He was 92 years old.

This article originally appeared in the 2024 May/June issue of Sporting Classics magazine.