Not many years ago, while residing in a non-sporting but delightfully cultured and refined community, I found that considerable indignation had been aroused among certain good neighbors and friends, because it had been said of me that I was willing to associate in the field with any loafer who was the owner of a dog and gun… I sadly reflected how their dispositions might have been sweetened and their lives made happier if they had yielded something to the particular type of frivolity which they deplored.

— Grover Cleveland, 22nd and 24th US President.

Grover Stephen Cleveland (1837-1908) began his public service in 1869 as sheriff of Buffalo, New York. In 1881 Buffalo residents elected him mayor, but he served only a few months before winning the New York gubernatorial election of 1882.

Two short years later Cleveland won election to the highest office in the land: President of the United States. He served his first term but lost the election of 1888 to Benjamin Harrison despite earning a greater number of popular votes. He won reelection, however, in 1892 and served from 1893 to 1897.

As president, he maintained the reputation of honesty that he had earned in the lower offices. Still, that didn’t prevent critics of his presidency from attacking his personal life, especially the time he spent hunting and fishing.

A number of US presidents engaged in outdoor pursuits while in office, but few or none ventured afield so often as Cleveland—he especially enjoyed duck hunting. And certainly no other leader of the free world endured continual attacks for hunting and fishing as he did.

Grover Cleveland filled two non-consecutive terms as US President. This portrait is from his first stint, which ran from 1885 to 1889. Photo: Eastman Johnson/Wikimedia Commons.

I base my assertions on reports I’ve read from old copies of the New York Times. It’s evident that the Times reported Cleveland’s hunting and fishing in favorable terms, but they also covered the criticism voiced by his opponents.

One notable report from the Times was based on Cleveland’s use of The Violet, a government vessel he employed for duck hunting and fishing and, on one occasion in March 1895, used to slip away from members of Congress of whom he was growing tired. He simply disappeared from an assembly, climbed aboard The Violet, and set a course for North Carolina and its saltwater marshes:

When the flag is flying from the White House it is understood by everybody in Washington who has been here long enough to understand the meaning of flags on public buildings that the President is at home. It is not always strictly correct, for the flag remains up after the President has gone out in the afternoon for a drive, or if he remains away a day after having begun the day in the White House.

Old Jerry, the servant who attends to this duty, is extremely particular not to incur censure for neglecting to raise it or for pulling it down too soon. On Monday of last week, however, he would have saved the useless expenditure of vehement language if he had lowered the flag sooner, or posted a notice at the White House gate to advise Congressional visitors of the fact that, although the flag was up, it did not mean that the President was “on board.” Jerry knew the President had begun the day in the White House, and he had raised the flag to make the fact known. When, just after breakfast, the President left for the steamboat wharf, to go on board The Violet, Jerry did not lower the flag on the Executive Mansion. In fact, he left it at the masthead until night, but he has not raised it any day since.

Of interest, the article went on the defend Cleveland’s use of The Violet and his unannounced duck hunt. One might guess that the newspaper writer was a duck hunter himself:

Only those who desire to be mean in their criticism of his use of the Government vessel are likely to find fault. The Violet is not a sumptuous yacht. She is a small, side-wheel steamer, without beauty lines, black below and regulation buff above. Her best cabin is not fitted up for any better person than her Captain . . .

In order that he might be fed, and yet not feed at the expense of the officers of the vessel, the larder was stocked with provisions at his [Cleveland’s] own expense. The officers made room for him very cheerfully and politely, to the extent of giving up to his use a stateroom and the dining room. None of these rooms is at all elegant. The vessel cannot by any extravagance of imagination be called a yacht.

Later newspaper accounts of this sudden trip reported that Cleveland was unable to hunt nearly as much as he wished:

On account of bad weather, the President has had only one day’s hunting yet. That was last Friday, when he killed sixteen brant and one large goose. Saturday was too stormy for sport, and the party remained aboard all day. Sunday was used up in cruising down to Ocracoke light house and back.

Storm signals are hoisted here, indicating a northeaster, which will prevent the President from shooting tomorrow. In which event it is probable that The Violet will be put about on the return trip to Washington.

The following is one of the more interesting excerpts. One has to wonder if only one sympathetic reporter wrote the Cleveland hunting and fishing articles, because each account I have read from his second term has been positive:

From Washington to Cleveland there have been but few Presidents who were fond of sports in the field and by the stream. Washington was a famous rifle shot and also a duck hunter, and carefully preserved his lands and river front from invasion by the casual shooter.

However, the last three Presidents have been noted for their fondness for shooting and fishing. [Rutherford B.] Hayes was a good wing shot, and nearly every Autumn before he became President used to go to the St. Clair Flats or the fine shooting grounds near Sandusky Bay, for a week or two of duck shooting, or else into what was then called the Black Swamp of Northwestern Ohio, for deer. He did not shoot, however, while he was President. Chester A. Arthur was passionately fond of that finest of all sports with the rod, salmon fishing. Each season during his executive term he used to take a fishing tour. He had been accustomed to lease a salmon river in Canada, but as a President cannot leave the United States while in office, he did not do so while he was in the White House. Instead he took a week each year at the fishing grounds of the Cuttyhunk Club [in Massachusetts], famed for the splendid sea bass.

President Cleveland is equally a devotee of the gun and the rod. Having unusual physical strength, he is able to handle with equal ease the 7½ or 8 pound bird gun for snipe, partridge, and quail, or the heavy 16 pound 8 bore duck gun affected by the Carroll Island Club, near Baltimore, where canvasback and redheads are thought to be the only birds worth the expense and trouble it costs to take them . . .

Mr. Cleveland is not fond of fine weapons in his hunting battery. He usually shoots American-built guns, his favorite being an eighty dollar Colt 12 bore. Or, if ducks be the game he expects to find, he uses a 10 bore Parker of the hammer pattern. He sometimes uses a 12 bore Scott hammer gun of the one hundred and twenty five dollar kind.

There are few better duck shots than the President. He usually loads with pretty heavy charges of powder; four and one half drams of black in his cartridge for duck and an ounce and one-eighth of No. 4 shot on top of the powder he thinks is about the correct thing. He shoots with great deliberation, and usually lets a duck get well up and away before he puts up his gun . . .

It is as a fisherman, however, that Mr. Cleveland is best known. He is equally at home on the river side, the lake shore, or out in a catboat on the salt sea. As far as is known, the President has not yet tried the king of angling sports, salmon fishing. But he can handle with equal skill the delicate light fly rod in taking trout, or the heavier bass fishing tackle, and the short stiff rod used by the deep sea fishermen, or the trolling line with which the voracious bluefish is captured. Of the three sports mentioned, Mr. Cleveland prefers the fishing in open sea. He can manage a catboat with the best of the craft, and is never so pleased as when he can stand in and out three or four miles from land, where a school of bluefish are around him. Then too, he can handle the two hundred yard line, so dear to the veteran of the Cuttyhunk Club, and beguile the great fifty pound striped bass with the skill of the most cunning of his fellows. It is no easy thing to drop the well baited hook seventy-five or eighty feet away in the boiling foam and make no splash in the doing, but the President accomplishes this with no more difficulty than he finds in writing the veto of an objectionable bill.

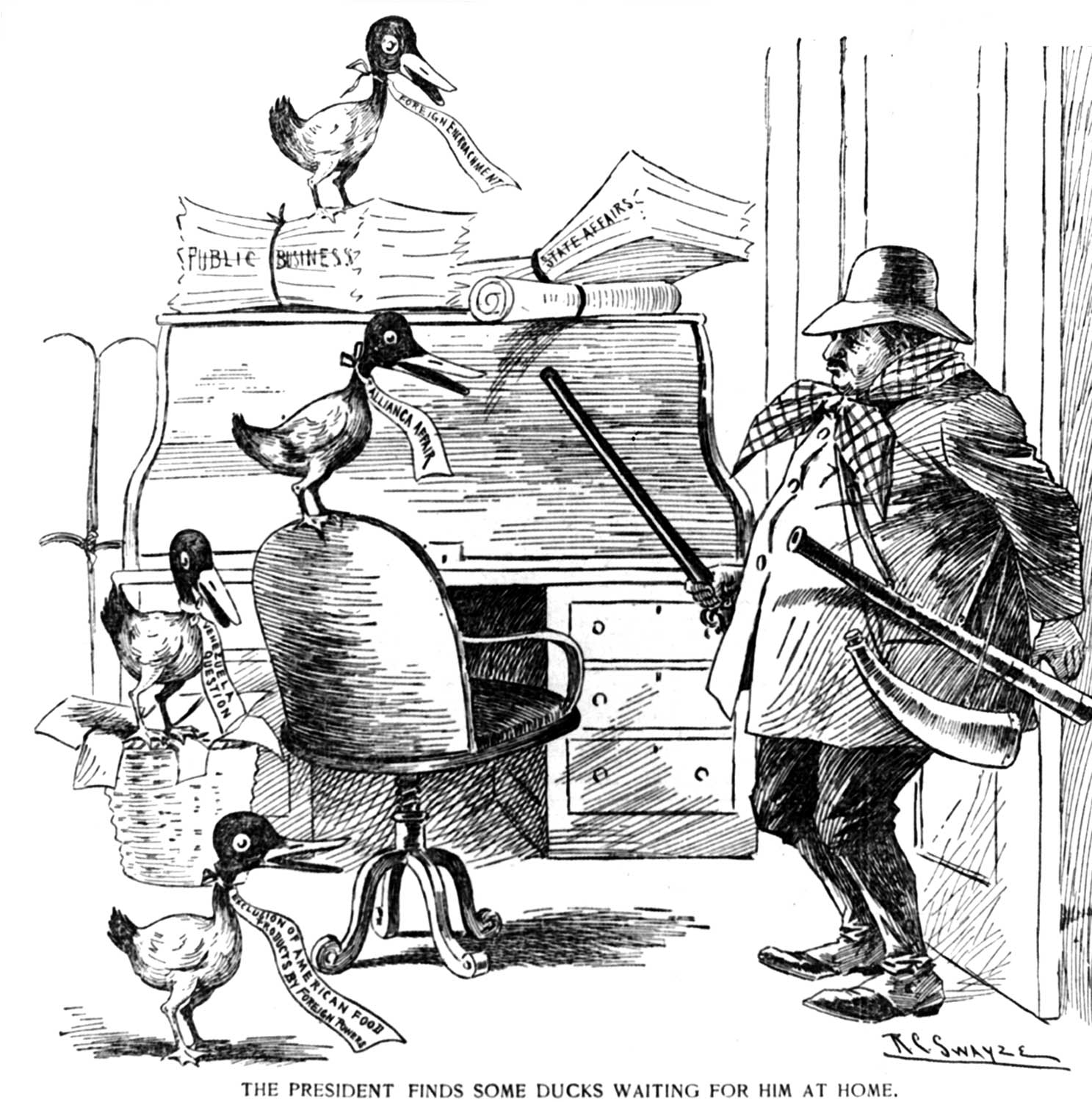

President Cleveland’s political adversaries pitted his passion for hunting against his duties as president. In this political cartoon by R. C. Swayze, Cleveland returns from hunting to find his office full of domestic and international issues—and ducks—that need his full attention.

Rest assured, especially during Cleveland’s second term in office, not a day went by without the New York Times reporting on the President’s actions in the White House and his frequent coming and goings, especially during the fall and winter months. There are a lot of these reports, several of which are both humorous and, from my point of view, totally admirable. For example, on January 29, 1895, the following news item began with: “The President has gone hunting, again.” Any waterfowler has really got to like that. But there is more, and it gets better:

With Mrs. Cleveland he attended a dinner given by the Attorney General last night, and then hastily changing his dress suit for duckling costume drove from the White House to the Seventh Street Wharf, where the lighthouse tender Maple was awaiting him. The little vessel at once steamed down the river. Her destination was Quantico, Virginia, twenty-five miles down the Potomac. Dr. O’Reilly, the companion of previous duck hunts, accompanied the President.

The President and party arrived at Quantico before daylight this morning. The President was on hand early to begin the day’s sport. Ducks were quite plentiful, and the President enjoyed the day’s sport and returned to his boat well satisfied with the quantity of game bagged.

The President returned to Washington tonight.

He killed thirteen ducks during the day.

Even after Cleveland finished his second term, the Times still covered his duck hunting. The news from November 3, 1900, was whether Cleveland would rather vote or shoot ducks:

Despite reports to the contrary, and the silence of the parties concerned, it is believed and stated on good authority that Glover Cleveland, the ex-President, is not going to forget himself or country so far as to go away duck shooting instead of staying at his Princeton home to cast his vote on Tuesday next [November 13], and that his most intimate friend, Commodore E.C. Benedict, is to do likewise at his home in Greenwich.

In the stronghold of Commodore Benedict’s mansion, at Indian Harbor, these two men of prominence are now abiding. They went from New York City yesterday on the yacht Oneida, which had just come off the dry dock at South Brooklyn. Despite their silence, it is understood that the captain of the Oneida has been ordered to take Mr. Cleveland to Princeton on Monday, so that he can vote the following day, and to bring him back to Indian Harbor on Wednesday.

It will take several days to get the Oneida stocked with provisions and her bunkers filled with coal for a trip such as it has been reported. Mr. Cleveland and Mr. Benedict were to start on immediately, and so escape the responsibility of voting. The crew of the Oneida has been notified to be ready for a cruise south, starting Monday, November 12. This apparently settles the question of the voting and the duck shooting.

From his time in the field, Cleveland had some good things to pass along, including his book, Fishing & Shooting Sketches. Some of the passages include helpful advice, such as this gem imploring you not to rush your shot when a quail covey flushes: “When the birds get up, if you chew tobacco spit over your shoulder before you shoot.” In other things he told it like it is:

It was on this day that I once or twice had my “eye wiped,” and I recall it even now with anything but satisfaction. It is a provoking thing to miss a fair shot, but to have your companion, after you have had your chance, knock down the bird by a long, hard shot makes one feel somewhat distressed. This we call “wiping the eye.” But I have always thought the sensation caused by this operation justified calling it “gouging the eye.”

I am a big fan of Cleveland. And it comes as no surprise that he knew exactly what the core of a waterfowler is, because he was one in the truest sense. This, too, is from his book:

Suppose the discomforts willingly endured by duck hunters were required of employees in an industrial establishment. There would be one place where a condition of strike would be constant and chronic. If it be said that the gratification of bringing down ducks pays for all the suffering of their pursuit, the question obtrudes itself, how is this compensation forthcoming in the stress of bad luck or no luck, and how is it that the duck hunting propensity survives all conditions and all fortunes?

I am satisfied that there is one way to account for the unyielding enthusiasm of those who hunt ducks and for their steady devotion to their favorite recreation: The Duck Hunter Is Born—Not Made.

Good stuff, that! And I’ll bet you’ll join me in hoping that he and Commodore Benedict didn’t lose any prime locations to other hunters because they were forced to delay their trip to vote.

Note: This article originally appeared in the 2015 March/April issue of Sporting Classics magazine.