With an eight-day window of October opportunity, we had just pounded out an upland hunter version of an Ironman: hunting seven to eight hours and ten to thirteen miles a day, rain or shine, through forest and fen, in pursuit of ruffed grouse and woodcock.

As we drank our morning coffee on day nine, I disingenuously offered to accompany Clay on one last morning hunt. His incredulous expression was accompanied by an emphatic: “No mas, man! I’m throwing in the towel! My dog just ate his breakfast from a prone position, my legs feel like Jell-O, and my hip flexors are grumbling that I only ingested three ibuprofen.”

If we rewind the tape eight days, this same Clay Frazer was singing a completely different tune. From the moment he hopped out of his truck, he was gung-ho, announcing he had just shaved 15 pounds off his newly chiseled physique through the alchemy of one of those “low index of pleasure” diets: no sugar, no carbs, no alcohol. But when I asked to see his “six-pack,” instead of pulling up his T-shirt, he reached for the contents within his cooler. I was relieved to know that the pleasure receptors of his cerebral cortex had not been damaged by his diabolical diet!

We donned our boots and headed out to some Oneida County land near my Tomahawk, Wisconsin, home. Clay drew first blood on a woodcock over his wirehaired pointing griffon, Max. Later he enthusiastically reenacted Max’s point for the benefit of those of us who had not witnessed it. This included our friend Bill Schaller, who had joined us for the first two days with his merry band of English cockers: Max, Sage, and Jade. After scoring on another doodle, Clay had bragging rights for day one.

Beauty in the clearing.

On day two I took our group to a potential honey hole. While turkey hunting in spring, I had explored a managed forest property near the Wisconsin River that looked very “woodcocky.” I noted multiple grouse flushes and frequent drumming. My good taste in habitat was verified by none other than Gary Zimmer, retired coordinating biologist for the Ruffed Grouse Society (RGS), who was just exiting “my” would-be honey hole as we were entering. Our hunt was a rubber-boot special—wet and wild. We heard grouse flushing and caught glimpses of blurred wings bending through the poplars, but we had to settle for another pair of woodcock that Clay and Max connected on in the thick stuff.

Our itinerary included two days in Oneida County followed by two days in adjacent Forest County, then back to Oneida for a day before heading to Carlton County in Minnesota for three days. So on day three we drove an hour and a half northeast to Forest County and met up with Clay’s dog trainer friend, Josh Kracht.

As the elder statesman of this expedition, I subscribed to the oft-recycled proverb “Old age and treachery always trump youth and vigor,” so for the last two days I had exhorted Clay from the relative comfort of the trails to “Get in there, boy, and bust up that brush—and make sure you’re flushing ’em in my direction.”

This strategy was clearly not paying off. Being slow of foot but nimble of wit, I switched allegiance to Satchel Paige’s paraphrase of Mark Twain: “Age is a case of mind over matter—if you don’t mind, it don’t matter.” And with that assurance I decided not to act my age, realizing only too late that I should have chosen Yogi Berra’s enigmatic maxim: “When you come to the fork in the road, take it.” It just might have given me pause before I recklessly dove into the fray.

Mark Herwig and Hunter marking a doodle.

Josh took us to a clear-cut that was seven to eight years old. It was bottomland but fairly dry. I was foolishly determined to share the glory with Clay on that 70 degree day. Trial by fire proved that I did not need Clay’s fancy diet to lose about five pounds in blood, sweat, and tears. The challenge involved negotiating my way through two-and-a-half-inch-thick sentry poplars that soared to 15 feet while an understory of tag alder groped for sunlight between my armpits and face. A basement of hungry blackberry vines extracted a blood toll while twice managing to untie the double-knotted laces of my hunting boots.

I toppled over like a hogtied calf at a rodeo event at least half a dozen times, all the while listening to Clay and Josh yelling, “Woodcock!” followed by the animated merriment of congratulations: “Nice shot!” “Dead bird, Max.” “Find the bird. Good boy!”

There were five woodcock on the tailgate by evening: Clay had a limit, Josh had a pair, and I had a pocketful of shiny once-fired 28-gauge hulls, and I appeared to be leaking nuggets of wisdom by the bucketful.

Back off, Wookie, these are my birds!

Day four was a bust. Why so few grouse when the DNR said that drumming counts this spring were up 30 percent in the northern region where we were hunting? Weather can always be a limiting factor in nesting and brood rearing success, but long term it all comes down to having good habitat.

In a recent article by outdoor writer Paul A. Smith of the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, Smith quotes Scott Walter of RGS, who said: “If we have enough young forest habitat to provide critical food and cover, grouse have shown us over the decades they can rebuild their numbers.” Unfortunately, our National Forests’ budgets are being cut, and along with them our investment in harvesting mature trees to create successional forests for wildlife enhancement.

An encouraging development in the 2014 Farm Bill authorized “Good Neighbor Authority” (GNA), under which the Wisconsin DNR has entered into an agreement with the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest to prepare, award, and administer timber sales. The hope is that this partnership will not only provide more wood for Wisconsin’s forest products industry, but also help to create and maintain healthy forest conditions.

On day five I climbed back in the saddle and was rewarded for my efforts. We returned to familiar turf at the Woodboro Lakes Wildlife Area, acreage RGS is partnering with Oneida County to groom for grouse hunting. We raised some doodles, and I tagged my first two woodcock of the hunt. Clay also took a pair and later added his first grouse of the year over Max’s spectacular point.

Later that evening I was shown that an old dog can learn a new trick. I had always breasted out my woodcock, but Clay proceeded to pluck our four woodcock and then use an herbal rub on the skin before roasting them over a charcoal fire on my Smokey Joe. He also cooked two of the birds with their entrails intact—his preferred method. He paired the cock bird with a baked butternut squash from his garden, a glass of Bourbon to accompany, and we feasted.

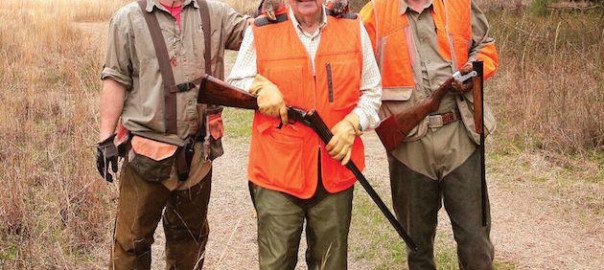

At the end of a 50-flush day.

As day six dawned we were driving down from our motel in Cloquet, Minnesota, to meet up with Mark Herwig, editor of Pheasants Forever Magazine, and Jared Wiklund, public relations manager for Pheasants Forever, who also doubled as our camp chef extraordinaire. Our endurance was flagging after five consecutive days of hunting in Wisconsin, but Mark and Jared’s enthusiasm and the quality of our Minnesota hunt reinvigorated us like a weary dog that catches a snoutful of fresh scent.

We split up on some private land that was also rubber-boot territory—it had rained four inches the previous week and three more in the past few days. Mark and I took Hunter, Mark’s springer, in one direction while Clay and Jared took Max and Jackson, Jared’s pointer, in another. When Hunter started to bray like a beagle, Mark said: “Get ready. That’s what he does when he’s pushing a runner.”

A huge grouse rousted out of the edge cover and attempted to cross the trail. Firing almost simultaneously, Mark and I hit this big boy as he banked right. Our combined shotstrings raked his back but preserved his beautiful fan and ample breast meat. This was the first of three “hawg ruffs” that we shot.

Mark let out a war whoop to confirm our kill to Clay and Jared, who responded in kind from their area not ten minutes later. By lunch break our group had scored four grouse and five woodcock.

Clay’s instant replay of Max’s point didn’t impress everyone.

While Mark took the afternoon off, Jared, Clay, and I were pumped for an afternoon hunt on Carlton County land. We hit some great cover and took three more woodcock and two grouse, one of which was Jared’s “hawg.” All of us agreed that the big boys appeared to lift off and fly slower, but maybe that was just an illusion that gave us an unconscious mental edge. Their crops were full of wintergreen berries, clover, and catkins as we examined our treasures over a celebratory beverage back at the truck.

Our road trip was on a crescendo. Day seven began with breakfast at a local diner where Mark introduced himself as a property owner in the area. It turned out that the cook was actually Mark’s neighbor, and she extended a personal invitation.

“I’ve got 175 acres and a bunch of woodcock that are always whitewashing my driveway. You’re welcome to come out and take care of that problem for me.”

Mark banked that opportunity for a later time, and we set out to explore some parcels in and around the Fond du Lac State Forest.

An understory of alders gropes for sunlight between armpits and face.

After hunting two areas without success, we hit the motherlode. A walk-in hunter trail ended in an enormous clear-cut, which Jared, Clay, and I decided to traverse—a very nasty business, full of slippery, jagged cuttings, blowdowns, seeps, and rivulets. Mark decided to backtrack to the truck in order to pick us up at our exit point. Our destination was a finger of nice-looking aspen, which turned out to be multiple fingers separated by multiple areas of slash.

In the next hour, on just one of those isolated fingers, we probably flushed 50 birds! There was a splash every six feet, and Clay and Jared were getting giddy. Every ten yards it was, “Jared, bird up,” or, “Clay, woodcock coming right at you!”

Once, however, my position as outside “linebacker” paid off. The woodcock were flushing from dense cover out to the clearing and then circling behind us back into the thick stuff. I limited out first on some very open shooting that challenged both my agility and alacrity. I didn’t know if I was going to get a high house station two or a low house station eight. The only thing for certain was that they would all be flying at Mach 1.

Jared’s “hawg ruff.”

My job on the perimeter was to shout a loud “Yep!” every few minutes, which was a positioning signal that Clay and then Jared would repeat to keep us all safely in line. At the end of a grueling but fruitful drive, the tailgate count was eight woodcock and two grouse.

We ate supper by campfire, rehashing the day’s events until a cold front moved in and rained out our party. We had just shared an amazing day of upland hunting; Jared posted on Facebook that this was the greatest two days of grouse and woodcock hunting that he had ever experienced.

Clay and I had one more day left on our Minnesota licenses, so we did our own freelancing the next day off a newly dozed logging road. We were rewarded with two more grouse and three woodcock before we headed home in the rain. Our inaugural G&W Ironman covered a distance of three marathons and demanded half the punishing duration of a Tour de France. It mustered all the grit and drama of an Ironman and, hands down, all the panache that only a “hunter-athlete,” clad in blaze orange, can exude.

When it comes to actually shooting ducks and geese over water, the action is on the small places – the inland lakes, the ponds and potholes, the floodings and creeks and backwaters. Day in and day out, that’s where the ducks are, and that’s where Chris Smith takes you.

When it comes to actually shooting ducks and geese over water, the action is on the small places – the inland lakes, the ponds and potholes, the floodings and creeks and backwaters. Day in and day out, that’s where the ducks are, and that’s where Chris Smith takes you.

However, each of these places requires a separate technique, alternate decoys spreads and calling concepts, and different gear to use. He tells you how to approach each type of hunting for the weather and conditions. He knows when and when not to call. He describes the skills a good waterfowl dog needs to know for each place, things he’s taught his succession of Labrador retrievers over the years. Buy Now