I have always felt that the ruffed grouse is the wariest, the swiftest and the most beautiful gamebird in the world. The bronzed magnificence of old gobblers allures me; so does the gleam of sunlight on the tall and craggy antlers of the whitetail. Yet a hunting season for me remains incomplete unless I can have a day or two with grouse.

Most of my hunting of this grand bird has been in the mountains of western North Carolina, of Virginia and of Pennsylvania. Usually before taking such a hunt, I hobnob with the natives, for occasionally one will be found who knows his gamebirds and animals.

To hear Dave Mellott talk, you would think the ruffed grouse no real bird at all, but a phantom of the first water. I encountered Dave in the hardware store a few nights before the season opened. You know how the hunters and all the would-be hunters foregather to talk it over before the bombardment begins, and each one sends everybody else to the place where game has not been seen.

“A gunnerman,” says the old Negro proverb, “will always lie.”

But Dave really seemed inclined to tell me where I might find some grouse. “I don’t mind giving the thing away,” he said, “because I can never hit a grouse. It seems that by the time I git my gun up, the blame birdie is out of sight. It don’t ever ’low me no chanst.”

“All you need, Dave,” I said, “is to practice being a little quicker.”

“I could git a whole heap quicker,” he answered, “and yet never git my sight on one of them things. When I hunts, I hunts; I ain’t out to compete with no lightnin’.”

And yet, Dave is a real hunter; he isn’t the kind of sportsman who thinks a bullet is a little bull, and who discovers whether his gun is loaded by looking down the barrel while manipulating the triggers. But he just can’t be bothered with grouse.

“Ain’t no sense in a bird flyin’ so fast,” he told me with some indignation. “Any shot that ever overtakes him will have its tongue hangin’ out!”

“Tell me where you saw these grouse, Dave, if you aren’t going after them.”

“It’s in Fulton County,” he answered, referring to that strange wild country in southern Pennsylvania close to the Potomac River—a county in which there are thousands of acres of primeval land but in which there is no railroad, no jail, no poorhouse.

“You go past Needmore, then on by Cuckoo, past the Meadow Ground and Indian Spring, and the place they call Bird-in-Hand. It’s right there, though it’s a lie. Leastways I ain’t never got no bird in hand there. Them little hills right by that country store that sells more bootleg than groceries—that’s the place. Them birds walk right across the road there by the store. But when they see me comin’, they don’t give me no chanst. I reckon they know who I is,” Dave ended, laughing. “But they wouldn’t take no account of you.”

As the great First Day approached and I made the momentous decision as to where I should go, I determined to take Dave Mellott’s word and try for the grouse of the little hills. I had a memorable day of it, and shall here record what appealed to me as its most interesting adventures.

The last night of October had hung mist-wreaths on all the trees; white mantles they were, that turned softly to pink and to gold as the still morning of the First Day brightened over the world. It was daybreak as I crossed the high ridge of the Tuscaroras and dipped into the fragrant, wild valley, which hasn’t changed very much since the days when Corn-planter, the Indian chief, found it his happy hunting ground right here in this world and this life.

Here and there in the lonely vale I could see tiny spires of smoke rising straight into the dewy morning air. Were the hard-working mountaineers rising betimes to go to labor or were the little home-stills right on the job? I hesitate to ask so unpatriotic a question; but I can testify that every cabin and farmhouse that I passed had about it a prevailing odor: it was that of apple-jack.

In my car I had my old dog, Starshine, but I never called her that. She was Star or Shine, according as my memory functioned on the first or second syllable of her name. She snuggled beside me on the front seat, her head flat on the windowsill, her eyes gleaming, her black nose twitching. I don’t want to go so far as to say that she “made game” every time we passed a farmhouse, but she certainly took a deep interest in these auras of distillation.

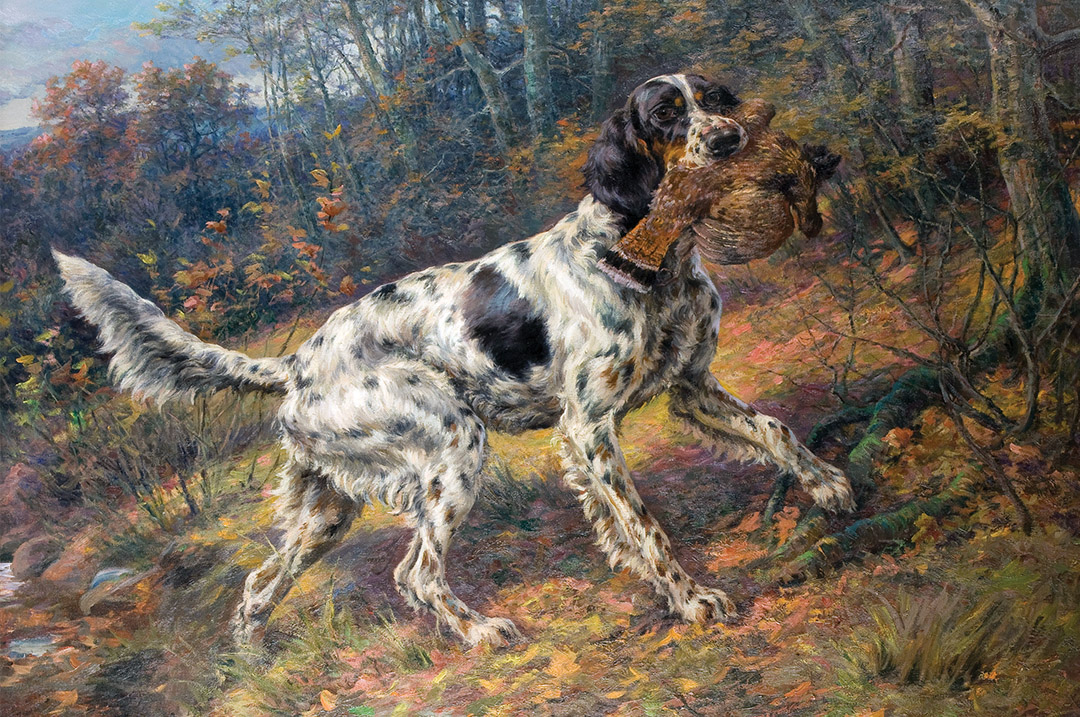

English Setter with Grouse by Edmund Henry Osthaus.

Past Needmore we sped in our Detroit Demon. Even a hunter can afford a flivver nowadays. Into Cuckoo we sailed. Cuckoo was asleep, and stayed so. If ever Cuckoo rears a distinguished son, he may become backdoor-keeper at the Dead Letter Office. On we bounded, Bird-in-Hand bound.

People have different ideas about the high moments of life. Perhaps mine are humbler than those of most people. But a drive early in the morning on the First Day, through a romantic, fragrant valley, seems to me about one of the keenest and most harmless pleasures that can come to a mortal.

I almost passed Bird-in-Hand, and would assuredly have done so but for the fact that here the valley closed in on the road; not high hills marching together, but strange little hills that had cantered away from their mother-mountains and had stopped here ages ago in a little, huddled group. These were the hills Dave Mellott had told me about. Here was the place in the road that the grouse used as their public playground. I was where I belonged.

Though the sun was now firing the dark fringes of pines that rimmed the hilltops, the inhabitants of Bird-in-Hand still snoozed. What’s the use of waking if you can be sleeping, and if there’s nothing to do if you get up? Parking my car in the city square, the same being a hitching yard with one post, I got Shine out, made sure that I had the shells I wanted and started down the misty road toward the foot of the first little hill. I knew that my car would be safe there for a month or two for that metropolis isn’t exactly overrun with city slickers. A fact that never fails to give me high hope for the future of our land is that there remains so much utterly wild and charming country.

Some 50 yards from where I had parked my car, I came to a place that looked like grouse, and smelled like grouse. I noticed a wild grapevine on the mossy fence bordering the way that had dim clusters of fruit. Farther back were discernible groups of sumac bushes, dully red. Studying the trees, I found them to be chiefly evergreens, but there were hickories as well, and oaks, alders along the stream that babbled back in the shadows, and thickets of birch and of chestnut-sprouts.

Hunters know what I mean. I know I am talking to men who know, not with men who think that a trailing vine is one that follows a scent for miles; that a running vine is one that gets up and goes if you come too near; and that it is a pleasant pastime for the true naturalist and sportsman to hunt for and to bring home the spots that the fawns have dropped.

There was light enough to shoot when Shine and I got fairly into the woods. The leaves were damp, so that we made little noise as we went up the aromatic little glade between two of the hills. We collected a rabbit en route—a poor thing to do early in the day. I thought I heard a grouse fly up ahead of us, but I could not be certain; nor did the dog give any evidence that she was aware of the presence of the prince of the woodland. Our glade ended in a wild shambles of grapevines, exhaling delicious odors. But the grouse were not there. I turned up a slope and climbed to the crest of the ridge.

I had had barely time to get my breath and to locate myself when, from the hollow beyond, a grouse flew up and came toward me. I saw that he was going to pass over me. He was traveling fast and high, but he fell to the shot and Shine retrieved him unruffled—the noblest gamebird of the whole world, I believe. He is the true aristocrat. Much as I love grouse hunting, I seldom kill one without misgivings. But my philosophy comes to my rescue just there and tells me that a kind Providence established gamebirds and animals for our especial use; and we do not live truly like nature’s own sons if we do not use all the bounties that she has so liberally and with matchless forethought provided for us.

There is always something ludicrous about these people who thoroughly enjoy their lamb, their beef and their chicken, and then devote the energy thus acquired to damning the poor hunter because he kills a deer or a wild goose or a grouse.

The bird I had just shot was a cock, in his prime, with perfect plumage; his ruff was exceptionally heavy and black. I wondered what had made him get up, for my dog and I had been too far off to frighten him. Then I heard someone walking. Evidently another hunter was in the wooded gulley below me. If so, might it not be a good plan for me to continue along the ridge parallel to him? He might flush another grouse, and the bird might take the same course as the first one. Probably the man was a Dave Mellott kind of hunter to whom the flight of the grouse was one of the wonders of the world.

Up the ridge I went, keeping pace with my grouse-flusher. Hardly a hundred yards from where the first shot had been made, I heard the soft thunder of the rise of another bird. Whether he had seen the line of flight of the first bird, or whether it was just my luck, I can never tell, but the second grouse came over my head at precisely the same angle as the first one. This shot was made also. I had a shamefaced feeling that the performance was too mechanical to be sporty. But I wasn’t gravely troubled, for the day was as yet young and I had a pair of mountain pheasants.

As these two grouse rose and came up the hill toward me, beating their way masterfully up to the treetops, I had, even while getting ready to shoot, a chance to watch their flight. It does not appear that any one can ever regard it as anything but thrilling. In our attempts at locomotion, we improve our cars, our airplanes. But the grouse, countless centuries ago, perfected a flight that has the finality of finished art. It is graceful, swift, powerful and yet strangely enigmatic. It attains what the finest automobile strives for: formidable power immediately available and under the most delicately adjusted control.

I do not know that it is a better flight than that of the quail, but it is far more impressive. And because the grouse is a bird of the forest and must do constant maneuvering while in flight, I think he handles himself more deftly than the bobwhite.

In the flight of the larger bird there is endless variety. Especially interesting to me are three features: one is the occasional silent rise, the big bird taking wing with hardly a sound; one is the instinctive habit of putting an obstruction between himself and his pursuer; and the other is his love of often going almost straight up to clear the trees and then tearing away over their tops, as if he were running the hundred yards in the Olympics. Indeed, the flight of birds alone would afford a man a lifelong study.

Believing that I had about used up my luck in the matter of having a stranger shoo grouse for me, I left him and turned back, going down the hill and across the road. Here, under a swarthy hemlock of massive proportions, Shine had her first opportunity to show that this was her party as well as mine. She found where a grouse had been walking that very morning. Plainly her behavior said so. She first stopped dead, her eyes fixed in a glassy stare, then she unlimbered a little. Her tail wagged; she broke point, but moved forward like a circus-dog walking on eggs.

Once she looked back at me in order to ascertain if I fully realized the importance of the business at hand. I tried to look sufficient and reassuring. She crossed the little stream that purls about the hemlock’s roots and then stopped by some alders. She went on noiselessly to a clump of wild raspberries that draped a fallen log. Here she froze right. I tingled. You know the feeling.

It was pretty thick ahead, and I didn’t know just where the bird would go. I decided it would have to be a quick shot. But who can ever be certain, unless he actually sees his game on the ground, just what will get up when his dog points in a thick place? I expected one grouse. To my consternation, three got up. And they got up as a covey.

I’m ashamed to confess it, but I thereafter joined the Dave Mellott class. I did select one bird, but just as I had my sight on him he melted into a young pine, and when I looked for another victim, all were gone. I deserved scorn, and the look Shine gave me expressed it sufficiently.

Probably one of these grouse offered me a shot a half-hour later. But I had the same chance of getting him as a Democrat has of getting in office in Pennsylvania. I walked under a spruce, and he went hurtling out from the dusky branches over my head. I fired wildly. Shine eyed me commiseratingly, as if to suggest that she was mortified to find me slipping. My feelings did not improve, nor did hers, for during the next hour or so we struck no game at all.

It was now near noon, and I was pretty well back in the little hills. It was a long way to the car. I decided to hunt back toward Bird-in-Hand. Shine managed to discover a small flight of woodcock in a boggy thicket, and three of these we secured—solemn, tiny gobblers, with all the dignity of high officials upon them.

A mile farther on we came rather unexpectedly to the borders of a wild field that must have been used at some time as a pasture. It was bordered by a stone fence over which wild roses wept and grapevines trained and teaberries hung in clusters. I felt that there ought to be a grouse here. And there was.

Shine stood him from the top of the old crumbled wall, and he went rocketing off across the old pasture. I was afraid that I had waited too long to shoot, but he fell like a plummet; a head-shot, I discovered later. Not long after this grouse had been secured, I reached Bird-in-Hand. A stray cow seemed to be trying to eat the upholstery of my car. Otherwise it was unmolested. In it, I packed away my game and my gun, then Shine and I went into the store.

“Well,” said the proprietor, “how many did you git?”

“I didn’t do so well,” I answered with a hunter’s evasion.

“They ain’t so plenty this year,” he offered, and they say their fur is mangy.”

To him, hunting always meant hunting rabbits.

“Did you ever see any grouse near here?” I asked.

“Grouse?” he questioned uncertainly. “What kind of a bug insect is that?”

But I did not answer, delighted that the presence of the grouse of the little hills was not known even to the lord proprietor of the place. I made a few purchases for Shine and me. Then we took the homeward road, fully determined to revisit so pleasant a country. ν

Note: Excerpted from Rutledge’s Hunter’s Choice, A Countryman Press Book published in 1946 by A.S. Barnes and Company.

Tales of Whitetails: Archibald Rutledge’s Great Deer-Hunting Stories

Tales of Whitetails: Archibald Rutledge’s Great Deer-Hunting Stories

Click Here to Buy Now

Archibald Rutledge—renowned outdoor writer, poet laureate, and authority on whitetails—is again returned to print in this stirring collection of thirty-five of his finest deer stories. $24.99