The guide put me ashore on the island. Just me and the grizzlies…an interesting feeling…isolated. My thoughts: I can’t walk out. Just one person knows how to find me.

I’d read many stories about grizzly bear hunting and attacks by the big, hump-backed predators. All were fearful but always they had happy endings. Of course, reason reminded, some didn’t live to write. In my 40s, old enough to know better, I was invincible. There wasn’t a fear corpuscle in my blood.

Certainly, my 338 Mag. and my smarts were more than enough…or were they? I had not been tested this way before.

Yes, it was better before Alaska required a guide’s presence with every out-of-state bear hunter. Back then, in 1973, the guide judged whether to let a man hunt alone — enjoy the solitude, make the decisions, feel the responsibility. Compared to my companion, I was experienced (deer and elk). So our guide, a genial man named Smith, had agreed to take my friend to some other place in the Archipelago of Alexander in southeast Alaska and simply leave me off to hunt alone.

As I pushed his boat off, Smith said, “I’ll be back for you at dusk.” Would that be nine, 10 or 11? I wondered. No matter; the day was mine, all of it, all mine alone.

My first decision after climbing the rocky shore and bank was to tie orange tape to a tree. Though confident I could find my way back, I still needed assurance this was the spot on a small island where all of the shoreline looked the same. Small on the map, but formidable to hike.

Great fallen trees made it formidable. Huge trunks lay on the ground like giant jackstraws. Accumulated through centuries, they were mossy but little decayed in the perpetually cool climate. I soon found a path between and over the deadfalls. A bear trail — had to be. No other path-making animals lived here. Probably the downed trees cause the bear to follow the same trails, not meander, I thought as I followed, checking my pinned-on commas. The sun didn’t show through the clouds or through the 20-story-high canopy of branches. The place was dim green.

Visibility was good in that only knee-high ferns covered the ground. But downed tree trunks blocked all but immediate ground views. My path led over one that had been notched-worn and torn over time by sharp claws. Unable to see beyond each tree I came to, I approached the notches slowly with my Winchester 70 at ready, one in the chamber. Each crossing was a sharp watch, a new adventure.

Another path intersected. I’d been moving mostly north on the island’s east side. The east-west path appeared to lead to the shore from higher ground.

“Just out of hibernation, the bears will be hungry and feeding on sedge grass close to shore,” Smith had told me. I turned right, then stopped to mark the intersection and my turn on a note pad.

Soon I came to many trees laid down parallel, the result of some particularly fierce wind. I climbed a high one and stood still, watching. No need to hide; bears see poorly. Maybe20 minutes later, having seen no movement, I went on. Though not productive, the tactic seemed reasonable since I had no local knowledge. I repeated it as I progressed eastward on a path about twice the width of a deer trail.

Mid-morning might not be feeding time, but these animals, essentially undisturbed and totally in charge, could eat anytime. Black bears did not live on this island — the grizzlies would kill them. No diversity here.

Crossing some tree trunks, where bears could not be seen but be surprised, began to get me jumpy. I walked along the top of one recently downed trunk to its pulled-out roots, higher. There I sat, ate a candy bar, watched and listened. The forest was spooky silent. The slight west breeze didn’t move the ferns. If it moved the foliage high above, I couldn’t hear it. But I did, faintly, hear the shore … incessant waves breaking on rocks. The sound comforted and drew me closer. I’d walk the forest above the shore looking for sedge grass and bears.

Crossing some tree trunks, where bears could not be seen but be surprised, began to get me jumpy. I walked along the top of one recently downed trunk to its pulled-out roots, higher. There I sat, ate a candy bar, watched and listened. The forest was spooky silent. The slight west breeze didn’t move the ferns. If it moved the foliage high above, I couldn’t hear it. But I did, faintly, hear the shore … incessant waves breaking on rocks. The sound comforted and drew me closer. I’d walk the forest above the shore looking for sedge grass and bears.

I followed the trail toward the ocean, where close to shore it slanted down. Whether luck or hunter’s instinct, I walked on straight to a small cliff falling to the ocean and overlooking a sort-of bay, my first unobstructed view. The shore appeared gradual and sandy. There was grass and there were three dark spots. My 10-power glasses revealed a sow with two cubs. Even the youngsters had pronounced shoulder humps. Just out of hibernation, apparently ravenous, all with heads down, they were mowing the grass in a narrow patch along the beach. I watched, hoping.

Now late-morning, most of an hour passed before the three were joined by a single. It was clearly larger. Probably a boar. But either sex was game unless cubs were present. The newcomer too started eating his way through the grass. A tough-to-kill animal, the grizzly was too far away for shooting. I had to close.

Quartering from behind me, the west wind prevented an approach through the forest. The beach offered low cover behind some long-ago lumbered and lost logs that had washed up onshore. The trail angled down. From there, at water’s edge, I could move below their sight in a crouch, then crawl where I had to.

Between the several logs, without cover, I waited until all heads were down, then moved slowly. To have alarmed the sow and her cubs would have more than spooked the boar. The breeze carried my scent to the sea. My thoughts: The bear can’t see well. “My” bear just came to feed. No hurry.

I inched closer, crawling on sand between the logs. Flotsam, mostly seaweed, littered the shore. I alternated hands to carry the rifle, using my forearm and elbow for support. Back then, my knees had not begun to hurt. It was easy.

Moving probably 50 yards in 20 minutes, I approached the sow where a log lay angled so that I had to crawl in the lapping waves. Chilly. I got to dry ground and knew it was true that man can’t live long in that water.

Four bear backs showed over the grass as I eased my camo cap and then my eyes over the next log. One stood taller wherever he walked. Of course, he was on the far side. Some weeds helped hide my tortoise-like crawl past the sow.

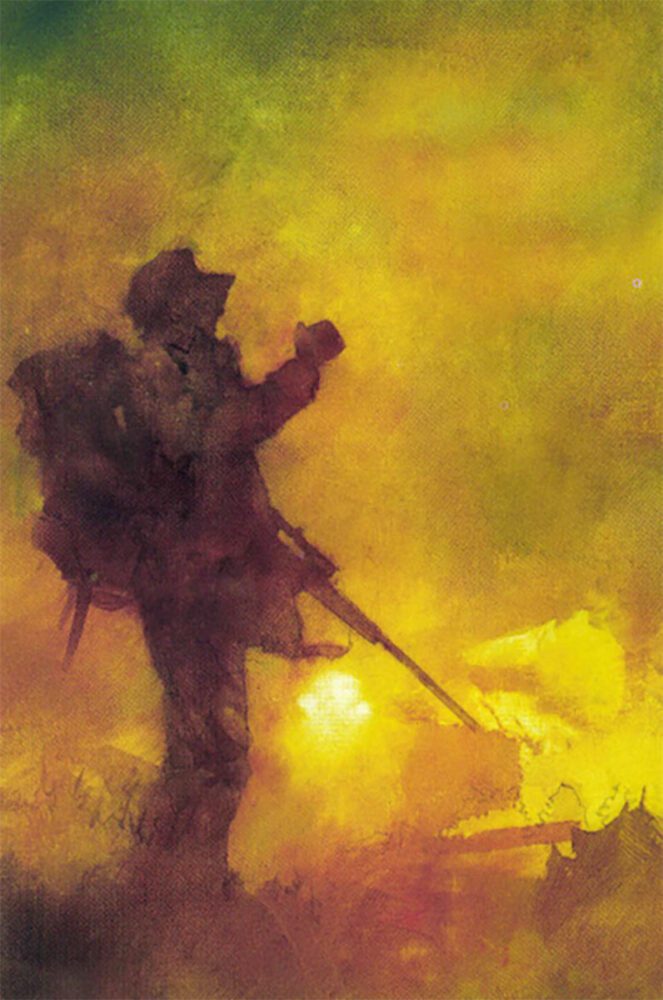

Finally to my target log, I commanded my heart to slow, peeked over, then rested my rifle on both gloves folded across the log. The bear fed straight at me through a swath of grass about 75 yards away.

With crosshairs steadily on, I waited for him to turn. He didn’t. Head down, his neck exposed, I knew I could take his spine. He would not run. He dropped at my shot.

His feet were still under him as I approached. Although it seemed unreasonable, I’d heard of grizzlies feigning death, then jumping the hunter. My reloaded 338 Mag. with safety off touched the bear’s nose. Nothing. It had been a sudden death.

Only then did I think to look For the sow; in my concentration I’d forgotten her. She, with her cubs, had disappeared at the completely foreign, sharp blast of the rifle. Again, all was quiet.

Long brown hairs flowed between my fingers as I felt for the bullet entry. I rolled him — it was a boar — and began to skin. While working, I paused occasionally to look around and to think back, mentally retracing my way.

Using all my strength to turn the big boar, I finally got the hide off his back and him off the hide. The paws and head were detached; one more skilled than I would dissect the hide from those parts. Then, surprised, I noticed the water was close. The 15-foot tide had come in. I couldn’t back-track my way in the sand.

Laid out flat, the hide looked plenty big. No point in measuring, even if I had a tape. He was a fine bear, taken fairly and instantly. I folded the paws across and rolled the hide to the head. It was a huge double-arm load. By the time I’d walked back a hundred yards, I had to put the heavy thing down – too much for my biceps. Then I remembered the nylon cord in my “fail safe” pocket. I wound and tied the hide and head, fashioning a sling to slide over my head. Thus, my back and neck took more of the load.

Biceps relieved a bit, I walked until the bear path showed, ahead and up. The big bundle blocked the near view. I feared falling. Also, I knew that my rifle was not handy. It was slung behind my shoulder with my load tied on front. Moving slowly — it would be hours before my pick-up – I partly felt my way with my feet.

The apprehension of crossing downed tree trunks into unseen space had lessened some, but I knew I was making a trail of blood smell. Couldn’t be helped.

Before long I came to a fork in the path, not marked on my map. I had not noticed it when angling in from the other direction. I put the hide down and rested a few minutes. What to do … Finally, I followed Yogi Berra’s advice and took it — the fork to the south, closer to the shore. Now it was 6 o’clock.

I hadn’t even noticed the wind until I heard it. Pausing, I watched the sway of the great trees, branched only near their 300-foot tops. How did their shallow roots hold? These rock islands, once mountain peaks, hadn’t decayed much over the eons of coolness. The wind seemed to be increasing. I wondered if the pic-up boat could handle the waves.

Made of metal, the boat was built strong, though it was barely large enough to carry the three of us. Seaman swear at the storm sin the Gulf of Alaska. They are fierce. I hoped the clouds and wind were just a local affair, not a Gulf storm. Uneasy about it, I labored down the bear path.

On reaching my first right-turn intersection, I got down on my knees and out of the bear “sling.” I haven’t eaten, I realized. Trail mix, jerky and rest with my back against a protecting trunk put the fatigue away. I thought, the ocean waves will be too much for the little boat, which soon grew to worry. I picked up my pace, found the orange-marked tree and sat down to watch and wait.

The waves weren’t bad. Of course they’re not, I realized, this is the island’s lee side. But the open water would be different.

Whatever, I could do nothing to hasten the boat’s arrival.

I had water and food for a couple of days and I could scavenge meat from the hide. I wouldn’t freeze and if necessary, I could use the bear hide as a blanket. If rain came, I could catch some.

An hour passed. I’d thought it through, put worry aside and came to a great sense of peace.

Aloneness is conducive to peace, and mine was a most remote aloneness — the only human on a far-away island. Grizzlies lived here, but they hadn’t been harassed, and I figured they held no animosity toward man, unless surprised. My scent was going to sea. I didn’t even need a fire.

Lying on my hack, watching the trees sway — extreme, I thought — my mind reviewed the day. How fortunate I’d been in this wonderland. Finding the bear, not losing my way, not falling, shooting well. I was comfortable here in this marvelously unique land. I waited and watched in the wind.

Instead of the small boat, the mother ship appeared. Fifty-five feet long, with catamaran hull and twin diesels, she nosed into the cove. Then the rowboat was lowered to come for me.

What joy my friends showed when I heaved up the hide and climbed aboard. They’d been worried. They didn’t know. They hadn’t experienced the gratification of aloneness and feeling peace in the face of peril.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 2005 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

Now, for the forty million Americans who hunt, here is the perfect companion. The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a collection of true hunting tales, told by some of the most courageous and clever sportsmen. The quest for adventure has touched all these writers, who convey the drama, tension, stamina, and sheer thrill of tracking down game. Buy Now

Now, for the forty million Americans who hunt, here is the perfect companion. The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a collection of true hunting tales, told by some of the most courageous and clever sportsmen. The quest for adventure has touched all these writers, who convey the drama, tension, stamina, and sheer thrill of tracking down game. Buy Now