It’s only natural that Greg Beecham should feel as he does. His dad, Tom Beecham…drilled drawing into him before the youngsters years had reached his teens.

Greg Beecham’s dusty brown felt hat rides high on his forehead, the way a cowboy sits straight on his horse. From beneath its drum, his probing eyes sweep the necklace of pond in the valley below the weather-fractured boulders where we sit. Behind us rises Wyoming’s Wind River Range.

On one of the red sandstone boulders, sheep-eating Indians scratched petroglyphs depicting their hunts. Greg tells me how the Shoshone herded bighorn sheep onto a trap floored with a lattice of pine logs and built over the edge of a low hill. Beneath the trap, he says, waited the Indians. When the sheep clamored onto the crude platform, their logs poked through the logs. Swinging heavy clubs, the Indians broke the legs of the luckless animals. Struggling to escape, the sheep scrambled over the edge of the trap, tumbling into the meadow below where other Indians waited with spears.

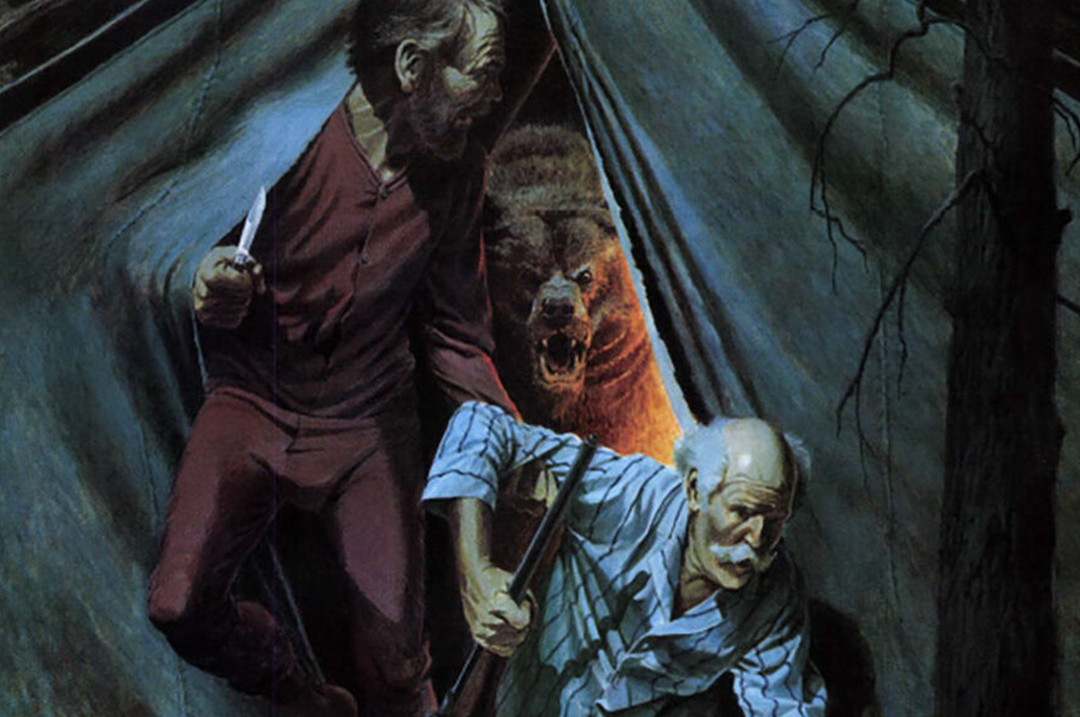

Snooze Ya Lose earned Beecham 2004 Artist of the Year honors from the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation.

Recounting the story, Greg’s mind may be placing the image of a massive ram in the racks. He may be seeing how a moose and her calf might look crossing the narrow stream that joins the willow-fringed ponds. He may be thinking of how the lower, oranger light that comes later in the day will deepen the color of the new green cottonwood leaves and strengthen the red bands of the sandstone outcrops that frame the valley.

Or Greg may be thinking of how few moose there are now that the wolves have spread from Yellowstone National Park 80 miles to the north. He tells me that in the Junior Valley, just north of Dubois where he, his wife Lu, son Sam and daughter Sarah make their home, the moose are gone. There were more than a handful when they settled here seven years ago. Elk harvests are down as well. He blames the decline on wolves, which killed his new black horse. The horse’s long course tail hangs on the wall behind his easel. His words are tinged with both bitterness and fatalism.

The fatalism is more a sense of reality than resignation. Above all else, it is reality that drives Greg’s art. To illustrate his point he recounts: “Last year at the Museum of Wildife Art miniature show, I had a coyote eating’ on a dead buffalo. There was a lot of blood. I called it The Organ Grinder. I thought it was educational as well as a good piece artistically. I want to convey the message: It’s not always the beauty and ninety of nature, but the reality of nature. Sometimes that’s beautiful too.”

Down Slope

As in Snooze Ya Lose, which earned Greg 2004 Artist of the Year honors from the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, at the core of every Beecham painting is good drawing. “You look at Bob Kuhn, who I think is the best wildlife painter that ever lived, and all the stuff in the background. It looks abstract, but it’s still drawn. Everything is drawn. I never want to lose the variation, and the paint itself.”

It’s only natural that Greg should feel as he does. His dad, Tom Beecham, the famed wildlife artist and illustrations of more than 30 years of Remington calendars, drilled drawing into Greg before the youngsters years had reached his teens. But drawing is more than the realistic reproduction of a scene. It’s the ability to manipulate structure in such a manner that the scene conveys thought and feeling. “A wildlife artist should be a storyteller,” Greg assets.

The Shoshone petroglyphs that we sit beneath are stories. They speak of the facts of the hunt and of the Indian’s gratitude to their gods for providing sustenance. With his finger, Greg traces the etching’s life line. “These have a unity,” he says. It is the same kind of cohesion that Greg seeks in his art.

On the TraiI of the Caribou is riveting with its play of gold on white and by the burning intensity in the wolves’ eyes.

“I have a theistic worldview. I’m a Christian and I look at this,” his hand moves across the tableau in from of us, “and friends would see the huge red rocks all around us and say, ‘Whoa, doesn’t this make you feel small?’ I say no. It makes me feel special. God could have made it black and white and barren, but he made it this way for us.

“So being out here, I rejoice and worship. It’s nice to have a genre, I guess, where I don’t have to question the ethics of what I’m doin’. Here’s a cool thing: In the book of Genesis, it says God created man in His own image, male and female. The only thing we know about God up until that point is that he created something from an idea. So the idea that I get to be an image-bearer to reflect His glory is an awesome thought for me as a Christian.”

Ethics, according to Tolstoy, is an essential component of art. In his essay, What is Art, the Russian author wrote that it is comprised of three elements: talent and technical skill, fresh perspective and a moral position. Greg laughs when he says that Tolstoy wasn’t pitching his tent by a new swing in some sort of philosophical terrain, but castigating Guy de Maupassant for writing dirty stories. Still, Tolstoy’s formula is based on principles that guide Greg as surely as if they were imprinted in his genes, which, to some degree, they may hav been.

A Leg Up.

Even with my untutored eye, I can see the evolution of his work from the period when variations of the color gold infused all of his paintings. Today, his colors are no less bold, but he is making greater use of contrast, even when doing subtle paintings like On the Trail of the Caribou, which depicts three Arctic wolves on a snow-field. He deploys light and shadow in a manner similar to the great Baroque painters from the Netherlands. Backlit, the wings of cruising egrets are luminescent against a gunmetal sky.

These paintings and a half-dozen others anchor the wall inside Gallery Di Tommaso in Jackson. Says manager Greg Fulton, “Greg puts the two together, an artsiness and the technical side.” He points to one of the works: “The drawing in this painting (New Life, a cow buffalo with the first calf of the season) is perfect. Every dimension of these animals is perfect. Then he uses his talent as an artist to set the mood.”

Creams and yellows, colors normally not associated with buffalo, dusty and shaggy and shedding their winter coats in spring, glisten on the back of the cow. Close by her flank totters the calf, painted a warm brown, precisely the color of those I saw driving across Yellowstone on my way to interview Greg. The cow’s head is turned slightly so she can keep her eye on the calf. He’s placed the pair on a dry plain before a brooding forest of dark yet distinct timber. The confrontation between glowing highlights on the cow and the threatening forest indeed celebrate the promise of new life.

Fulton notes that the compelling moods in Greg’s work transcend traditional wildlife art. He refers to the artist as “a master.”

Beecham traces the life-line in a Shoshone petroglyph, which inspires much of his art.

Unlike many wildlife artists, Greg enjoys laying down a heavy layer of oils. With brush and knife, he builds a physical texture that, by itself, creates shadow and highlight and more depth. It is a technique that he’s been continuously developing for years. He believes “you should be pushing yourself to understand form and content. You can learn from Robert Bateman or Stephen Quiller, but you take their ideas into your studio and you make it your own and it never looks like either of their work.”

Like most other wildlife artists, Greg works from photographs. His studio is a wreck, a blizzard of magazines and papers covers the floor. Against his book cases slump more of the same, a kind of intellectual talus. Uneven stacks of slides, most dusty, cling precariously on the lip of the shelf on which sits his computer. Rather than work out his compositions with pencil on a sketch pad, he deploys all the forces of PhotoShop.

In his mind, Greg sees a landscape. He searches thousands of his photos, scanned into the computer’s memory until he finds something close. Then comes the photo of an elk, running across a dirt road. The image is blurred, but so what. He enlarges it, erases the background and cuts and pastes it into the landscape. He inserts more elk photos, perhaps taken years apart. He scales them to size and puts them into the composition. Next he adds a blow-down and maybe a struggling lodgepole pine seedling. He moves the elements of the picture around until they almost suit him. Then he turns to the canvas to paint.

Down for a Drink is an enchanting study in light and color.

Technique aside, it’s the sense of place that drives Greg. “To me, being a wildlife artist, that says I have to be out here in it.” And in it he is. Over sandwiches and diet colas in a local diner — we both forego buns and fries — he talks to me about moving to Dubois, how his son Sam killed his first elk when he was 12 and how his wife Lu deftly wields a .270 and made a stunning shot on a running antelope at 400 yards.

Afterwards, we’re back in his pickup, heading out past the Diamond D Ranch just north of town. “I’ve got a friend who works here,” Greg says. “I go out Brandin’ with him every year, help him calvin’ once in a while, and movin’ cows. I’ve learned an awful lot about horses and riding just being with him. I like the western cowboy culture and being a part of it. I also like the fat that my son’s graduation class had only 22 kids. There’s some opportunities they don’t have, but they can get them now, anywhere, and they’ll always have this.

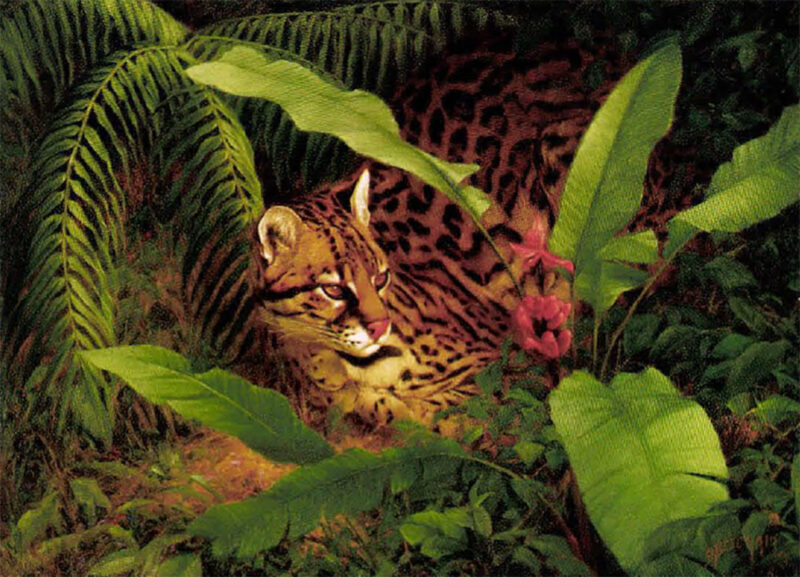

EL Mano Del Creador depicts an ocelot at rest in lush jungle growth.

“I don’t think there’s a vehicle in town that doesn’t have a gun in it. In fact, when we first moved here, the deputy sheriff came out to the house to help us get out vehicles registered and he said: ‘You know, be a real good idea for you to get a concealed weapons permit, not for any other reason than it’s not if, but when, you hit a deer and you gotta put it down.’”

How different is this rural reality from the dairy farm in the foothills of the Catskills where Greg was raised. His mom and dad were Coloradans. The West colored the family blood. Mentored by his father, Greg knew he was going to be a wildlife artist before he finished the 8h grade. After a stint in the Navy — he felt honor-bound to see in Vietnam and was disappointed that he was aboard a destroyer for only six days before its fire-support mission was concluded and it was rotated off the coast — he studied art at Southern Oregon State College.

He met and married Lu and lived in Seattle for 19 years until Boeing’s merger with McDonald-Douglas. The Beechams then decided to pull up stakes and head for a country where the haze of liberalism had yet to obscure the West of his father’s youth. Dubois, with fewer than 900 souls, had been recommended by a wildlife artist friend. They’d planned for Lu to be a stay-at-home mom,. But she, morally committed as he, began volunteering in the schools, the Medical Board, Quilt Guild and Booster Club. “At times she spent 12 hours a day on her volunteer work,” Greg laughs. “So she took the job of school business manager, cut back her hours and got pay and benefits!”

In September Reprise, Beecham strived to capture the wild gyrations of a courting bull moose.

It was a good thing for them both. Lu was in school with their kids and her paycheck carried them during lean times. Despite a first-full of awards and stints as feature artist at dozens of major shows and steady sales of his paintings, the cost of raising children demanded more income. Admittedly uneasy with self-promotion and unskilled at marketing, Greg thought he’’d have to go to work for someone else. Then Gallery Di Tomasso began to carry his work, and paychecks arrived with much more frequency.

Artist’s are supposed to keep hours we normal folks would consider crazy. Not so Greg. He’s a nine-to-fiver. Up soon after the sun brushes the mountains, he may kick up the fire in the wood stove beneath the mount of his 6 x 7 elk, then trudge out to feed the family’s three horses in the small paddock north of their log home. Breakfast done, he drives Sarah to school in town and then around the corner to his studio on a quiet back street. There he settles in.

To loosen his style and make it more interpretive, Greg has been doing one small painting, a 9 x 12, per day, and he’s happy with the results. Lunch is a 98-cent cup of noodles moistened with tap water and warmed in the microwave. While he eats, he plays solitaire on the compute to rest his mind.

On those afternoons when the painting’s done, or as much as can be done until it dries, and there’s no track meet and he and Sarah have had their work-out in the weight room, Greg will get the horses and drive up through the red rock country, through sparse stands of pine, to a ridge overlooking the Absorokas. He’ll saddle the horses, plush a bit of sage, crush it between his fingers and breathe deeply its pungent perfume. “I love sage,” he told me. Sometimes, returning from a ride with Lu or Sarah, he’ll pick a sprig and carry it back to his studio, so much does it remind him of home.

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now