Which came first, the chicken or the egg? We’ll never know, but I can tell you the great duck guns came after the ammunition. Certainly there were heavy, large-bore shotguns in 6, 8 and 10 gauges, but even at that their payloads of shot were modest. The 10-gauge at the turn of the 19th Century carried 1 1/4 ounces of shot.

By 1880 the breech-loading side-by-side double as we know it was near full development with the Purdey sliding underbolt and the Scott spindle; in 1909 Boss & Co. patented its superb over/under. Not to be left in the dust, in 1883 Christopher Spencer launched his pump-action shotgun that included for a few extra dollars screw-on chokes, which were a set of three rings − Improved Cylinder, Modified and Full – that screwed on at the tip of the muzzle. The Spencer, later bought by surplus arms magnate Francis Bannerman, used a toggle action that at best was clunky. However, 10 years later, in 1893, Winchester introduced its John Browning-designed Model 1893 pump. By then, smokeless powder began shoving blackpowder out of the ammunition formulary and the 1893’s action proved to be too weak for the higher pressures of smokeless. Browning did a rework, and the Winchester 1897 was born. It stayed in the line for 50 years. In 1903 Browning again struck paydirt with his long recoil-action Automatic 5 that lasted nearly a century in the Browning catalog. Concurrently, in 1903, Danish gunsmith Christer Sjörgren launched his semi-auto Normal that is part and parcel of today’s inertia-style semi autos. Great Duck Guns indeed.

A.H. Fox HE-Grade Super Fox (restocked) with a Tom Turpin duck call, cork decoy with cypress bottom board and poplar head by Carl Eswine, Shawneetown, Illinois, and Super X shells.

In 1921, the Western Cartridge Company in Alton, Illinois, owned by Franklin Olin and his sons Spencer and John, brought forth a newly designed shotshell that used progressive-burning propellant. Blackpowder exploded and rammed the shot down the barrel; Western’s propellant shoved the shot along in ever progressing speed. For years, shotshell manufacturers had tried various ways to prevent pellet deformation and shot stringing. The new Western Super X used the contemporary paper hull made by winding glued paper into a tube, aging it, then cutting it to length, crimping on the brass head and loading it with powder, wads and shot, finally rolling the crimp with its over-shot wad. Rolled crimps lasted into the 1940s and are still occasionally used because they need less of the hull’s overall length than the more common folded crimp. In addition, the Olin’s copper-plated the shot, not so much as to add lubricity as they are jostled down the barrel, but to prevent pellet fusing from the white-hot propellant gasses that seeped past the card and felt wad column. The end result was a shotgun shell that cut the length of the shot string (a shotshell’s pattern when fired has both width and length) at least in half, providing increased killing power.

1924 Parker disassembled.

At the time, some began seriously questioning how the relationship of chamber, bore and choke affected the downrange performance of the Super X. In 1921 a Twin Falls, Idaho, lawyer E. M. Sweeley and ballistics expert Charles Askins, perhaps the best-known gun writer in the nation at that time, set about developing a shotgun barrel that would take advantage of the Super X’s ballistics.

Using a single-barrel A. H. Fox trap gun, Askins and Sweeley shot patterns and had the bore continually altered in search of the best combination. Their final boring joined a tightly tapered chamber (at that time, most were straight cylinders or only mildly tapering) to an extended forcing cone that provided a gentle transition of the shot into the barrel, which was overbored to .740-inch from the traditional .725-/.729-inch and finally a long taper into a tight .040-inch constricted choke.

When they finished, the A. H. Fox HE-Grade Super Fox was born. For my money it was the first real duck gun. The 9-pound-plus Fox used the heaviest 0 barrels on a wider, heavier action with great attention to the boring of the barrels. As was customary to any shotgun of the day, the customer could order it in any stock configuration and dimensions he desired. Barrels were 30 or 32 inches and otherwise very plainly finished with just a squiggle of engraving around the case-hardened action. The 12-gauge Super Fox was made in both 2 3/4- and 3-inch chambers. A 3-inch chambered 20 gauge was also made and are somewhat rare. Fox offered a single trigger, but most had double triggers. Of note is that the Fox action had only three parts, the trigger, sear and hammer, which also carried the firing pin; very little to go wrong. The action used only coiled springs that even when broken often function.

The Parker forend shows excellent inletting of iron.

I own two Super Foxes, one 2 3/4-inch shipped from A. H. Fox in 1924 and the other, a 3-inch chambered, shipped in 1923. Some knuckle dragger cut the barrels of the 2 3/4-inch gun from 32 to 30 perhaps to shoot steel shot, who knows, so it wears Briley X Thinwall chokes. The other 3-inch gun has original 30-inch barrels. Using my digital barrel micrometer I measured the bores of the 3-inch gun; the right barrel’s cylinder bore is .741-inch and the choke constriction is .040-inch and the taper to the choke from the cylinder bore is 4 1/2 inches. The left barrel measures .741-inch before the lead to the choke which is 4 inches, and the constriction is .044-inch. Just what Askins and Sweeley ordered!

Close-up of the steel reinforcing web welded between the barrels of an L.C. Smith Long Range.

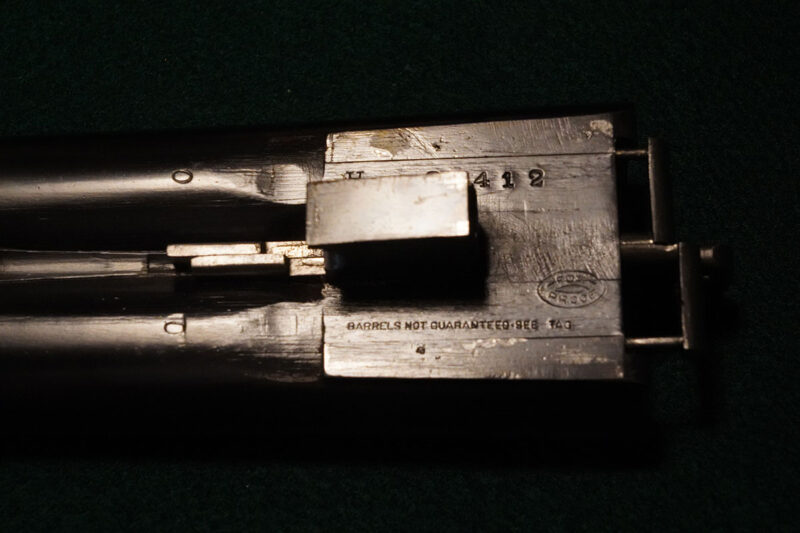

When the Super Fox came on the market, Fox’s advertising promised, “80-percent patterns at 40 yards,” intended for use with factory-fresh Western Super X shells. When hunters began stuffing it with handloads and other lesser ammunition, hate mail began pouring into Fox’s Philadelphia factory. Very quickly the barrel flats were stamped “Barrels Not Guaranteed See Tag,” which elaborated on the quality of ammunition for which the guarantee was extended.

Not to be outdone, L. C. Smith (by 1921 long sold to the Hunter Arms Company by Lyman C. Smith who by then made typewriters) sought to make a competitor to the Super Fox. Called alternately the Wildfowl or Long Range, it was little more than a field-grade gun in which the chambers were lengthened to 3 inches and on most a 3-inch reinforcing web was welded between the barrels extending from near the end of the forcing cone area.

An L.C. Smith showing the decorative “LONG RANGE” stamp.

The beauty or the beast of the L. C. Smith is that while it is America’s only sidelock-style shotgun of that era, it comes at a price. The sidelock in all its British grandeur offers excellent trigger pulls, a safety sear and broad canvas for engraving. The Smith delivers on some but not all. The trigger pulls can be excellent and there’s lots of space for engraving, but L. C.’s sidelock has two flaws: One, it does not have an intercepting sear to catch the hammer should the gun be dropped or jarred. Second, and more insidious, is the fact that the back of the sideplates are square. Square, too, is the tight inletting of the plates into the wood. The result? Cracking of the head of the stock. I bought a Smith Long Range over the phone and the seller swore on stacked Bibles that the stock was not cracked. On arrival it looked good, but after a couple of weeks in my gun safe with a Goldenrod keeping the humidity low, it looked like the map of a Montana drainage. My now-retired master gunsmith, Greg Wolf, painstakingly put it back together and delivered it with the suggestion of shooting only very light loads in the future. I shot one goose with it using Kent’s Tungsten-Matrix and it rests forever in the safe.

Super Fox barrel flats showing “Barrels not Guaranteed” inscription, O-weight barrels and Fox proof mark.

My 1925 Smith has a Hunter-One single-selective trigger that selects just great provided you want to shoot the left barrel first. The cylinder-bore diameter of the right barrel is .734-inch and the choke constriction is .046-inch; the left barrel goes .732-inch and the choke .037-inch. While these barrels measure a little on the wide side between standard and Fox’s .740-inch, it’s hard to say that this was much other than their standard field gun dolled up.

Of course, not mentioning Parker Bros. would lead to my burning at the stake and justifiably so. Parker has become synonymous with perhaps the premier quality American-made shotgun. Actually, all of our American greats were made very well and beautifully, so let’s not get into hair pullin’ and eye gougin’ over that. I will say I often like just looking at the forend of my 1924 Parker. The excellent inletting of the forend catch is a thing of beauty, not even surpassed by my fine British Henry Atkin (from Purdey’s). The stock is odd for that era because it has a straight comb with drops of 1 1/2-inch at both comb and heel. Like so much of my life the factory record book for my particular serial number has been lost, and I therefore have no idea in what configuration it left Parker’s Meriden, Connecticut, factory. It also has a straight grip, not unusual, but for an otherwise work-a-day VHE-Grade, somewhat puzzling. I showed it to a couple Parker afficionados and they said they thought it to be all original.

Buttstock cracks in L.C. Smith Long Range is typical of many L.C. Smith shotguns.

Parker, and in fact all of the American-made shotguns of that era were not hand made in the British tradition where each part began as a block or strip of steel that was hand shaped and fitted, but rather very carefully assembled from a bin of machine-made parts that were then hand fitted. Certainly not as simple as today’s AR-15s into which you can toss a jumble of parts and come up shooting, but complex enough that virtually any replacement part must be hand fitted.

My Parker started life on Maryland’s Eastern Shore and, because of its configuration, might have been a live-pigeon gun. Who knows? At any rate it’s meant for business with 32-inch 3-inch-chambered barrels that measure in the right barrel at .728-inch with a constriction of .038-inch and the left at .729-inch and .040-inch constriction. Measuring the choke forcing cones both were right at 2 inches.

Maryland Eastern Shore hunter Altie Langford killed 10,000 ducks and geese a year for the market wit hhis Remington Model 11 semi-auto. Photo: The Harry Walsh Collection of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, St. Michaels, Maryland.

I shoot my Parker just for fun once a year with Tungsten-Matrix or one of the recent Bismuth loads. The trigger guard always bites me on my middle finger, so I tape up first.

The Repeaters

Not to be slighted, we should look at two of the trend-setting repeaters; the Winchester Model 12 pump came along shortly after the 1903 Browning Automatic 5 and both were a staple in the blind for decades. Winchester introduced the Model 12 Heavy Duck in 1931 and Browning upped the Auto 5 to 3 inches in 1958.

Although the Belgian-made Browning Auto 5 was the top-drawer of the long-recoil semi-autos, the “American” semi-auto was less expensive and with “Five Shots Under Your Finger,” as Browning’s advertising boasted, became a favorite of market hunters. When John Browning first offered his Auto 5 to Winchester, he sought a royalty on each Auto 5 made, not the cash buyout as with his previous designs. Winchester declined. Remington was within a heartbeat of a deal for the manufacturing rights to the Auto 5 when Remington’s President Marcellus Hartley dropped dead of a heart attack as Browning waited in his outer office. Frustrated, Browning then took his design to Fabrique Nationale in Belgium and there the Auto 5s were made from 1903 until the 1975 when production shifted to B. C. Miroku in Japan.

In 1905 Browning licensed Remington to produce a slightly modified version of his Auto 5. Initially called the Remington Autoloading Shotgun it was renamed the Model 11 in 1911. In the 1906 Remington catalog the Autoloading Shotgun listed for $40. Maryland Eastern Shore market hunter Altie Langford who gunned the Elliott Island marshes from 1900 to 1918 claimed to have killed 10,000 ducks and geese a year. When the Remington Autoloading Shotgun came along, he bought one. For cleaning and lubrication, he sluiced it out “every so often” with gasoline. The long recoil-style shotgun allows the barrel ring to impact the rear front of the wooden forend as the barrel slams forward. Langford said he had to replace the forend at least once a year from the battering it took.

Winchester Model 12 Heavy Duck with Winchester Super Speed shell box, early P.S. Olt duck call and Super X shells.

The Winchester Model 12 Heavy Duck was released on February 15, 1935, just 13 days after President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s signing of the Federal Migratory Bird Act that, among other things, legislated the reduction of the magazine capacity of all repeating shotguns to no more than two shots. Hence the Model 12 Heavy Duck came with its wooden two-shot magazine restricting plug installed. In addition, the stock was cut a bit shorter at 13 5/8 inches as opposed to the regular Model 12’s stock of 14 inches to accommodate heavy hunting clothes. Inserted into the buttstock was a lead plug to add recoil-dampening weight and to balance the heavier than standard full-choked barrel, and a 1-inch solid red-rubber pad completed the stock. Offered in 30- or 32-inch barrels, you could order a Heavy Duck with any choke you wished, but full was the standard of the day. In Winchester’s literature introducing the Heavy Duck it mentions using Winchester Brush Loads (spreader loads) for quail, woodcock and other close-range birds. The barrels were all stamped “For Super Speed and Super X,” subtle advertising of the Winchester-Western brands of ammunition. The advantage of the Model 12 pump action was that you could shoot any 12-gauge load because the cycling is by strong arm not mechanical. One of my most enjoyable shotguns to shoot every season is my Model 12 Heavy Duck made in 1942, the year I was born. Its bore is .729-inch – within acceptable manufacturing standards − and the choke .0355-inch, which was Winchester’s standard full choke constriction. My favorite wears a solid Winchester Matted Rib that added to its price, which in 1942 with rib was $73.20.

The lore of waterfowl hunting is deep, perhaps deeper in tradition than any other hunting. Decoys, calls, shotguns, ammunition, boats, literature — the list goes on — and in each instance there are long historic roots that extend back decades and even centuries. Because we are blessed with ammunition like Kent’s Tungsten-Matrix and bismuth loads, so long as your dad’s or grandad’s shotgun is safe to shoot with modern shotgun-shell pressures, you can take it to the blind and again let it hear the hens quacking in the marsh or the geese awakening with their raucous honks as the sun peels back the stygian dark of night and hopefully always will.

Featuring more than 200 decoys and hundreds of historical photos, maps and documents Lloyd Newberry traces the fascinating story of the Cobb Family through three generations. It’s a chronicle that historians and folk-art collectors will find both educational and enjoyable. Nathan Cobb and his family were iconic figures in the maritime and waterfowl gunning history of North America. With an ancestry and gene flow directly back to Plymouth Rock, Nathan’s father was a Cape Cod whaler and shipbuilder. Seeking a warmer climate for the women in his family who were suffering from tuberculosis, Nathan sailed south to homestead on Virginia’s Eastern Shore. Buy Now

Featuring more than 200 decoys and hundreds of historical photos, maps and documents Lloyd Newberry traces the fascinating story of the Cobb Family through three generations. It’s a chronicle that historians and folk-art collectors will find both educational and enjoyable. Nathan Cobb and his family were iconic figures in the maritime and waterfowl gunning history of North America. With an ancestry and gene flow directly back to Plymouth Rock, Nathan’s father was a Cape Cod whaler and shipbuilder. Seeking a warmer climate for the women in his family who were suffering from tuberculosis, Nathan sailed south to homestead on Virginia’s Eastern Shore. Buy Now