The most difficult part of nurturing a great dog is keeping yourself straight.

I think of the dogs I have loved.

Bird dogs. Yours and mine.

I think of the ways I have loved them.

This time, aside loyalty and devotion—almost a given within kind and understanding kenneling—let’s exalt character and performance. Canine charisma.

Some thoughts:

Over the 70-year better part of a man’s existence on this tenuous piece of earth— through the 50-some I’ve kenneled of my own, through hunting casts near and far, the field-trialing wars of 60-some seasons, from judging invitations, be it back pasture bird hunters’ contentions to major circuit horseback championships on the most fabled grounds of the land, by way of gallery attendance at the highest dog tests men can contrive—I’ve had the rare privilege to watch many hundreds of good dogs exhibit their wares. A lifetime sprinkling, which is all any man ever gets, of those that ascended to extraordinary, who were beyond great.

I’ve talked on many occasions with the men and women who ran them, who, as myself now or then—found no higher station in life beyond the too-brief privilege of their company.

Of those scarce, perhaps half-a-hundred dogs across seven decades that were truly sovereign, who now hunt the bird-rich edges of broader heavens—I pray—all are rightfully enshrined in one of two superlative Halls of Fame. Joining others, already accessioned, as supreme.

One of these physically exists under rafters and shingles in cathedrals of reverence, near the burg of Grand Junction, Tennessee. It has many supporters, bountiful donations, a foundation to perpetuate its purpose, multiple gatherings every year to accompany and celebrate its inductees and reasons for being. There are statues in its gardens, memorials within its halls, paintings upon its walls. Fund-raising overtures to keep it going. A publicity staff to assure that it is never forgotten. A journal to publish and canonize its events.

The other has no physical location, yet is ever more substantial. You cannot find it at a single place, not Union Springs, Tallahassee, Thomasville, Grand Rapids, Washington State or Tennessee. It has in largess no statues in its gardens, no halls to walk, or walls to adorn. It has neither need nor presence of a formal foundation to proclaim its purpose, nor a publicity staff to herald its existence, fund-raising consortium to keep it afloat, or journal to laud its eminence. Its human attendants can be lavishly rich or pauper poor. Yet it exists ironclad, for now and all time to come, as it has for all time that has been.

It has memorials, but rarely of bronze. There might be a small cemetery, a tasteful, traditional paling of rusting iron or weathered wood. Though more likely, and as expressively, just a moderate token of remembrance.

Maybe a simple stone marking the spot by a gurgling brook where a man goes to sit in October, with the yellow leaves tumbling down, when his years are running short and he travels with a cane, where once he hunted, and when he is in need of his one best and truest friend.

Perhaps the old blackened collar nailed to the trunk of a great oak tree, a sunken mound of earth adorned by ferns beneath a long-ago stump that bears roughly the shape of a heart, the pencil-starred page in a leather shooter’s diary on a roll-top desk, a hand-scribbled poem of four lines stuck between the favorite pages of a Gene Hill book, the old, chewed-up reclining chair that for the past 40 years a man has refused to throw out for a new one, the collar that hangs upon the bedpost each and every night, the small cherry box on the mantle with a precious few ounces of ash inside, a tuft of silken hair by an ancient yellow photograph from some special day, the venerable old bell on the wall that sang through many a mountain hollow.

And then, perhaps its greatest memorials lie ever beyond vision, cannot be seen at all, yet exist indelibly, tangibly, in a million golden memories. Of a day with a great dog so blessed it carried you to the moon, and you could look back to Earth, and feel that you had ascended to the highest emotive pinnacle of your life.

If you love and recognize that dogs, of all the creatures on Earth, are the greatest and purest gift of Goodness, and what the most brilliant and courageous are incredibly capable of, have witnessed and lived within the precious aura of the brief, best days of their lives, then you will have known when that happened, that it was true.

In this unseen and sacred shrine, the only paintings rest upon the walls of a man’s heart. Then, only for a while, only for the space a man or woman lives, for they will have been humbly commissioned and, in the majority of cases, gain no historical or societal value after he or she is gone.

The emblems of this colossal and hallowed place are many and treasured, but small.

There are many more dogs here than at Grand Junction. For they are not voted in by committee, but honored by mutual accord and respect across a much larger expanse of America. Under the vast spiritual eaves of many thousands of knowing dog men and women whose one best and equally legitimate criteria for induction is that “here, under the ethereal cathedral of equivalent acclamation, we honor the single-most thrilling, most brilliant dogs of our lifetimes.”

There are dogs here, in fact, that are not always blue of blood or pure of lineage, some even that are sullied by breed or absent of pedigree. “Drops,” if you will. But they are here because they belong to be, and any man who would disparage by caste any one of them is not truly a dog man. Or caught up in his own fenced-in arrogance, a failing no dog ever deigns to.

Dogs and Riders by John Tracy

Truth is, I solidly believe, if it were not for the human-contrived crucible and crux of competition, and the oft-times foibles of artifice and political digressions it breeds, all the greatest dogs of history could be honored under one roof, be it ethereal or constructed of board and timber. For the attributes of a great dog are the same— except for conceding one single and defining criteria, that of range and the properties of venue, which in cases have been exaggerated to extreme, sanctifying perhaps unjustly above all others the tremendous desire of select great dogs to skewer the horizon. Other than range, which in itself is often limited or encouraged . . . instilled . . . into the majority of dogs by environment and degree of discipline, it can be veritably argued that the traits of a great foot dog and a great horseback dog are, again, the same.

I have two old friends, Sam and Nida Giddens. They very successfully campaign horseback dogs in all-age pointing dog stakes. Glory dogs. Which, plus all else, must have run and range. They have and have had some good field trial dogs, dogs that can win: two, maybe three, that were great. They’ve been dog folks all their lives. They know dogs. I knew them in the early years when they didn’t trial, but bird hunted. They had good dogs then too. A Brittany, a pointer and a setter in particular I remember well. One wasn’t fancy, the other two bled blue.

I’d wager if I asked them to run through the attributes that made their best dogs tops for shank’s mare bird hunting, Pat and Buck, for instance, and the things that made Bud Lite and Bud’s Shadow, their trial dogs, tops now, the list would vary negligibly, but for range.

Should I ask you as well, as one who has been there, as a dog man or woman . . . which was the greatest dog of your lifetime, and what . . . dog or gyp . . . were the things that made “him” great . . . truly charismatic?

But for the one exception, I’ll bet your answer, and those of your peers, whether you followed him on foot or horse, would be almost identical:

Snap, speed, style and class, from puppyhood. Intelligence. Astounding nose. Uncommonly full of point and/or retrieve. An innate lean toward holding a point once established, drinking in the scent without creeping. (Ever heard the old expression, “he goes to sleep on point?”) Superb athleticism. Endless, never-quit endurance. Hardiness and durability. Heart and courage. Ablaze with natural hunt. Whitehot with passion for birds, along with a sometimes dangerous and unquenchable, kill-himself-if-you-would-let-him drive to find them. An uncanny knack for knowing where to go to do it when the chips are down, sometimes in places you’d believe he wouldn’t. A remarkable ability to “pattern” birds on a given day and grounds, laying out to similar and likely cover. Unfailing memory of any and every place he ever found a bird. Boldness and independence, with just enough swing and bend to be biddable. Love of the gun. Hunting at a range the country requires. A tendency for a high head, an unbelievable instinct for reading and using the wind, handling birds . . . going to them decisively, but standing well off them when he does. A can’t-take-your-eyes-off-him merry way of going. Proclivity for hanging the front. Incredible marking ability. Style and intensity on game so consistently eloquent it absolutely wrings your breath away every time. A natural and immediate bent to honor another dog who finds first. (W-e-l-l, as a general rule, though we all know some great dogs are too hugely competitive to want too.) A compelling desire to check on you now and then, to want to know where you are. Casting ahead intelligently with your travel.

The list could go on, for the character of a truly great dog is profound. But if you are a veritable dog man or woman, and have answered honestly, we don’t have to cite the rest anyhow. I think we’d agree by now that any attempts at separate accounts invariably drift to one.

Maybe one other paramount thing: Keen and quick to absorb intelligent training, with the mental level-headedness and fortitude to do it without losing composure and style.

BUT . . . about this thing called “training.” With an honestly great dog, it’s a misnomer, and most folks give themselves far more credit than they deserve. Be careful with “training,” lest you get in his way. A much more prudent analogy and approach, I believe, is “coaching,” the largest of which is helping him any way you can, without crimping him down, or creating a roadblock or being too slow to get out of his way. Mainly, giving him well-thought opportunities, which wisely encourage what you want him to be, and enable him to reach his top potential, which is phenomenal.

Great dogs are mostly born that way. About the only thing you will ever really teach them, and then if you do it right, is “Whoa!” Retrievers, “Stay!” And “Come!” Beyond that, if you’re sage, they’ll teach you. They have the wares and intelligence— if we don’t botch it up—to be great on their own. Even in spite of us sometimes, if we don’t really get electric and stupid. The best advice I ever received on dogs, from the greatest dog coach maybe I ever knew, was “don’t throw it away.”

If I’ve learned nothing else across all these wonderful, but more than occasionally frustrating years, it’s that the most difficult part of nurturing a great dog is keeping yourself straight, being half as wise and great as they are.

There are a lot of ways you love a dog. With a great one, just be divinely thankful that somehow the stars aligned, and for a while he is (was) yours.

There was a time when the world spun more gently, when family was the axis of its existence and folks lived closer to the land. A time when a gun was no less valuable to the scheme of being than a Bible or a blade, when a hunting dog could be found under the front porch and a fishing pole sat ready in a chimney corner

There was a time when the world spun more gently, when family was the axis of its existence and folks lived closer to the land. A time when a gun was no less valuable to the scheme of being than a Bible or a blade, when a hunting dog could be found under the front porch and a fishing pole sat ready in a chimney corner

There was an age, a space of innocence, freedom and fascination, where every day brought another revelation, and tommorow could never come fast enough. When, as boys and girls, we learned as much from woods and waters as from a spelling book.

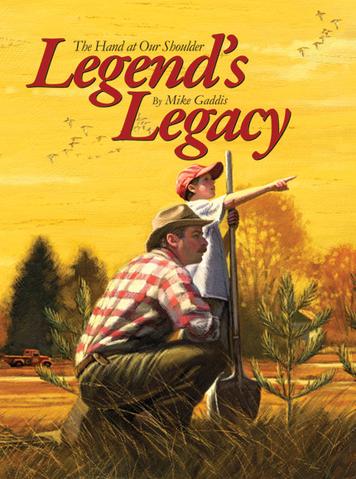

Most of all, there were moments of infinite beauty and sharing, when someone laid a hand at our shoulder and led us there. So that later we might lead another, in turn.

Here, in parables of incomparable warmth and intonation, the author of the celebrated books, Jenny Willow and Zip Zap, explores the enchanting realm of outdoor mentorship. Not only in kind and gentle remembrances, but in intuitive vignettes, present and future.

Legend’s Legacy stands unparalleled as an affecting commemoration of the most endearing aspects of our sporting traditions—an inspiring tribute to those who cared, who taught us then and guide us still. Buy Now