Gordon MacQuarrie stands well in the front ranks of those who collectively gave us what must be reckoned as the golden age of American sporting literature. Among his contemporaries were South Carolinians Havilah Babcock and Archibald Rutledge; Robert Ruark from neighboring North Carolina; Tennessee’s Nash Buckingham; Jack O’Connor from Idaho; New Englanders such as Edmund Ware Smith, Art MacDougall, and Burton Spiller; Californian John Taintor Foote (his roots were in the Midwest); and a host of slightly lesser lights, including a bevy of gun writers, several notable magazine editors, and giants of literature whose work transcended the description of sporting scribes, such as Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner.

A number of these individuals earned their livelihoods through what came to be described as freelance writing, while for others literary pursuits were, in essence, a sidelight to their main line of work. Babcock, for example, was a college professor; Rutledge taught at an exclusive prep school before turning to writing full time; and Buckingham sort of plundered around in a variety of pursuits while living a life devoted to dogs, waterfowling, and upland game hunting.

Gordon MacQuarrie doesn’t exactly fit the framework of the writers of this era. He was almost literally an ink-stained wretch who was America’s first full-time outdoor newspaper writer. In many senses, he has to be reckoned one of the first sporting humorists as well, a predecessor to funny-bone ticklers such as Ed Zern or, more recently, Pat McManus.

From the depths of the Great Depression (MacQuarrie’s first magazine article appeared in Outdoor Life in 1931, and later that year the first of the Old Duck Hunters stories, for which he is best remembered, graced the pages of Sports Afield) until his death from a heart attack on November 10, 1956, this giant of sporting letters entertained millions of readers and provided a literary legacy that still shines as brightly today as newly burnished silver. He wrote well over a hundred magazine pieces, most of which appeared in one of the so-called “Big Three” (Field & Stream, Outdoor Life, and Sports Afield). On the surface of matters, that may not seem overly impressive—it averages out to roughly six feature articles a year, with some modern outdoor writers churning out a hundred or more articles annually—but it must be remembered that from 1936 onward he was also the full-time outdoor man at the Milwaukee Journal.

It is a bit of a stretch to say, as Keith Crowley does at one point in his fine biography, Gordon MacQuarrie: The Story of an Old Duck Hunter, that MacQuarrie was “the first professional outdoor writer in the nation.” Perhaps it’s a matter of semantics, but to my way of thinking, the manner in which someone earns his daily bread is his profession. If “professional” is viewed in those terms, numerous individuals who earned their entire livelihood as sporting scribes preceded MacQuarrie. The only notable difference is that most were freelancers while he was a newspaper employee. Nonetheless, there can be no argument that individuals such as the senior Charles Askins, Horace Kephart, Archibald Rutledge (he relied on writing for his livelihood from his retirement from teaching in the early 1930s onward), and even George Bird Grinnell were professionals in every sense of the word—except perhaps for drawing a weekly paycheck. That being duly recognized, MacQuarrie does stand unchallenged as the first full-time newspaper outdoor writer.

Sadly, as is the case with most newspaper material from yesteryear, whether ephemeral in nature or of a timeless quality, much of the work which lies at the heart of MacQuarrie’s career—his newspaper columns and features—is inaccessible for all but the most assiduous of researchers. Yet posterity is blessed by the bounty of what is easily available in other ways. The aforementioned biography by Keith Crowley is useful not only in providing fine insight into a life well lived and a stellar career, but it offers welcome “extras” such as an appendix, “Gordon MacQuarrie’s Life and Works,” which notes landmark moments in his too-short years (1900-1956), as well as a complete list of his magazine publications.

Everyone who is intrigued by MacQuarrie—I defy any lover of sporting letters, any soul who enjoys the conviviality of like-minded individuals or just a tale well told, to say the man was a boring or even indifferent writer—needs to read Crowley’s biography. It is the sort of treatment needed for any number of his contemporaries that does not currently exist. However, the book is not the place to start but rather a hearty and satisfying dessert to be enjoyed at the end of a multi-course literary meal of MacQuarrie’s offerings.

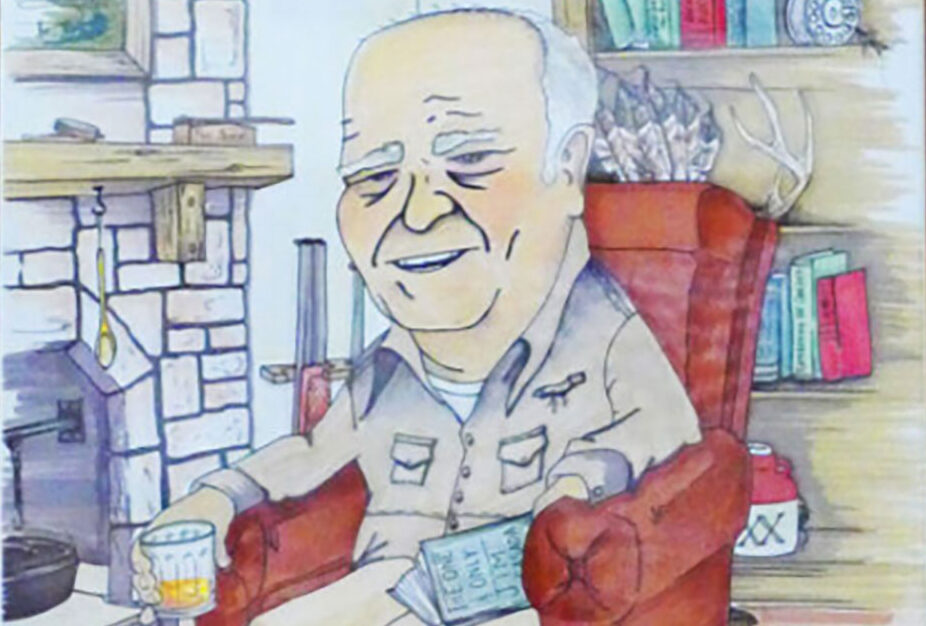

For an introduction to MacQuarrie, go to the true source, the flowing fountainhead of his tales of the Old Duck Hunters. The details are simple enough: Stackpole Publishing brought out the first edition of Stories of the Old Duck Hunters and Other Drivel in 1967, and beginning in 1983, Willow Creek Press gave us a bevy of anthologies. They include the volume just noted, along with More Stories of the Old Duck Hunters (1983) and The Last Stories of the Old Duck Hunters (1985). All three were compiled and edited by Zack Taylor, but it appears his input was minimal; in each of the volumes, Taylor’s input amounts to just a few hundred words. Posterity might have wished for more, but the fact remains that MacQuarrie’s stories stand tall all by themselves. Initially published individually, the books were later reissued as a trilogy in uniform binding and with a slipcase.

In the final volume of the Old Duck Hunters trilogy, Taylor commented, “My only regret—and one I know I share with thousands—[is] that unless some new unsuspected cache turns up, it must end here.” No new cache was unearthed, although I would venture to say some enterprising researcher could find enough meat for yet another anthology by digging through MacQuarrie’s newspaper columns and revisiting the 120-odd magazine articles he wrote. Indeed, there were two further collections with Taylor’s name appearing as the editor and compiler of both: MacQuarrie Miscellany: Featuring the “Lost” Old Duck Hunter’s Stories and Other Tales (1987) and Fly Fishing with MacQuarrie (1995). None of these anthologies are particularly rare, although you can expect to fork over $40 or more for all of them in decent condition, but collectively they open wide a window on MacQuarrie’s world.

And what a place of joy that world was. Every man among the tightly knit group forming the Old Duck Hunters soon becomes a vicarious buddy, and chances are pretty darn good most readers will have someone in their own circle of sporting friends with remarkably similar characteristics. On top of that, in the MacQuarrie Miscellany, you get one of the most harrowing accounts of danger in the outdoors ever written, “The Armistice Day Storm.” In its own distinct way, the piece is as gripping as any of Jim Corbett’s tales of dealing with man-eaters or Sam Baker’s daring deeds from the Scottish Highlands to Asia and Africa.

MacQuarrie was a giant in what might well be reckoned the golden age of outdoor writing, and unlike contemporaries such as O’Connor, Ruark, Keith, or Hemingway, he didn’t need trips to exotic locales or hunts for game beyond the dreams of the average individual to hold readers in thrall. He could take a Joe Lunchbucket setting and the type of hunting available to the common man and turn it into a setting of joy and grandeur. Read some of his work, which retains a consistently high level of excellence, and I think you’ll agree. Better still, chances are excellent that it will strike a responsive personal chord because you have known remarkably similar experiences in your own sporting life.

Jim Casada is the editor-at-large for Sporting Classics. View more of his work at jimcasadaoutdoors.com, and be sure to subscribe to the magazine for his column and features.