Soon, as it has for well over 100 years, it will begin — the annual migration of the field-trial faithful, pointing-dog division, to the northern prairies. It’s their version of summer camp, the place they go to escape the stifling heat of the southern United States and, for two hectic months, saddle their horses, turn loose their dogs, and work them on wild birds in big, wide-open country.

According to conventional wisdom, one good summer on the prairies contributes as much to a field-trial dog’s development as two years anywhere else. Sharptails — “chickens” in the vernacular — have always been the bread-and-butter bird, with Huns playing a supporting role, and pheasants making the occasional cameo.

Allen Vincent works a pointer near Columbus, North Dakota.

Most of the prairie pilgrims are tough, squinty-eyed professional trainers, but there’s also a sprinkling of serious amateurs, the kind who face the pros on their own terms without giving an inch. Some travel in gleaming multiple-vehicle caravans; others pull one-horse trailers behind rusty pickups. But they all run on the same fuel: the particular hopes, dreams, and aspirations engendered, and embodied, by a pointing dog capable of competing at the highest level.

Their destinations vary, but you’ll find the majority of camps within a 100-mile radius of the point where Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and North Dakota meet. Many have been in continuous use for decades; the storied Gates camp near Broomhill, Manitoba, dates to the 1930s. Creature comforts are few on the prairies whether you stand on two legs or four, and while communication has improved tremendously in the cellphone era it hasn’t been that long since a letter addressed to “General Delivery” was about the only way to get a message through.

The summer training season traditionally kicks off July 15, peaks in late August and early September with the running of the various chicken championships (the Dominion, the Saskatchewan, the All-American, etc.) and winds down quickly after that.

What the season lacks in duration, however, it makes up for in intensity. The days seem charged with it. As much a proving ground as a training ground, the prairies are the crucible where young prospects are tested to see if they measure up to the promise of their blood. The dogs that pass receive the benefit of further education, learning to run to the front, use the wind, and stand off their game.

For older dogs, the prairies are where they knock the rust off and restore the bright, gleaming edge that catches a judge’s eye and keeps them in contention trial after trial. The bottom line? While it’s possible to develop a major-circuit field-trial contender without the benefit of prairie training, it’s a little like enrolling in calculus when you haven’t taken algebra — you’re gonna have a lot of catching up to do.

A pointer in training.

A few summers ago, I had the pleasure of spending several days at the Columbus, North Dakota, camp shared by top professional trainers Allen Vincent of Oklahoma and Larry Huffman of Mississippi. The camp was originally established by another Oklahoma pro, the late Gary Pinalto — a man so tough that, even while undergoing chemotherapy for the cancer that would eventually kill him, he refused to take a day off from training.

“We’d come to camp and his wife would drive him to Minot for chemo,” Vincent recalled. “When they got back he’d be so weak he could barely get out of the truck, but he’d always say ‘Let’s saddle up and work dogs.’ And we always did.”

Pinalto’s unflagging dedication propelled two dogs he trained and handled to the pinnacle of the field trial world, the National Championship at Grand Junction, Tennessee: Lipan, who won in 1995, and Texas Trailrider, the winner in 2003. Larry Huffman has also trained and handled two winners of the National: Whippoorwill Wild Card (1999) and Whippoorwill Wild Agin (2008). They’re two of the record six winners of the National bred by Larry’s father, Field Trial Hall of Famer Dr. Jack Huffman.

A few miles west of the Vincent–Huffman camp, fellow pros Ricky Furney of Georgia and Steve Hurdle of Tennessee share a camp. Both Furney and Hurdle are, like Huffman, two-time winners of the National. Clearly, if your goal is to develop bird dogs of searing pace, soaring range, and uncommon bird-finding ability, the prairies of northwest North Dakota are a darn good place to do it.

Allen Vincent steadies a young pointer. Field-trialers agree that one summer on the prairies is worth two years anywhere else.

Growing up as he did in a bird dog–field trial family, Larry Huffman spent his first summer on the prairies when he was 12. That was more than 40 years ago, and he hasn’t missed a summer since. Along the way, he’s shared the camps of some of the greatest pros ever to blow a whistle: John Gardner, Marshall Loftin, Faye Throneberry, Tommy Davis, et. al. Huffman learned something from each and every one of them, but he credits Davis for teaching him the most valuable lesson of all, the same lesson Allen Vincent learned from Gary Pinalto: that no matter how you slice it, there’s no substitute for plain, old-fashioned work.

And let me tell you, these guys do work. After three days in the saddle trying desperately to keep up with them as they galloped over the prairies in pursuit of their dogs — dogs that were for the most part white dots on the horizon —I was so stiff and sore I could barely walk. Not that I’ve ever been mistaken for an equestrian. Indeed, over the years I’ve formulated what I call Davis’s First Law of Working Dogs from Horseback: The only disadvantage is the requirement of the horse.

For pros such as Huffman and Vincent, of course, saddles are essentially the offices where they conduct most of their important business. They sit a horse as comfortably as most of us sit in our recliners. One morning I watched Vincent draw abreast of a hard-running pointer and, in one smooth continuous motion, swing down from his saddle, clip a rope to the dog’s collar, and swing back into the saddle again. When he saw that I’d been watching, he grinned and said, “Not bad for a gray-haired man.”

Prairies offer miles of land to work young pointers on.

We rose every morning in the black dark, gulping coffee and grabbing a granola bar before loading dogs and horses into trailers, driving a few miles, and parking wherever Huffman and Vincent had decided there was enough country to work all the dogs that needed to be worked that day. We’d turn loose just as the sun boiled up, the dogs streaking away as if shot from cannons, their handlers cantering after them, singing all the while.

The first find would come with the prairies bathed in honeyed light, and we’d gallop to the spot to find a pointer standing tall, proud, and pop-eyed with intensity. Then the sharptails would rise, their snowy breasts flashing in the sun, and a pistol would go crack!, and the dog would stand motionless and resolute through it all until his handler grabbed him by the collar and whistled him on.

There was the fire and abandon of the younger dogs and the poise and polish of the veterans; there were dogs with bright futures, dogs that could go either way, and dogs whose early promise had gone unfulfilled and whose owners had sent them north hoping for something like a miracle, one final shot at redemption.

Whether you stand on two legs or four, creature comforts on the prairies are few.

And that, finally, is what you come to understand: that as much as the prairies are about cool mornings and accommodating birds and wide horizons and all the lessons they have to teach a pointing dog, they’re really about the more enduring currency of hopes and dreams.

Subscribe to Sporting Classics today to get more feature-length articles and columns.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 2015 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

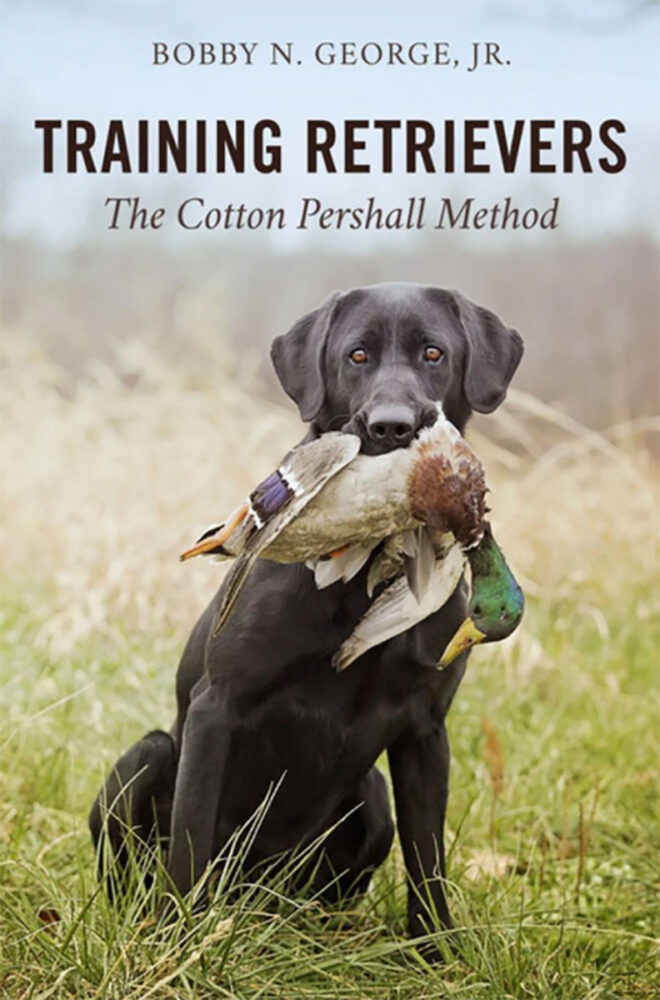

In the opinion of many, nobody was more influential or had a greater impact on retrievers—their training, handling, and breeding—than Cotton Pershall. This book was a command performance, because thousands of dog owners and trainers requested that Pershall’s methods be set down for generations to follow. Through the eyes and words of professional trainer Bobby N. George, Jr. that’s exactly what happened.

In the opinion of many, nobody was more influential or had a greater impact on retrievers—their training, handling, and breeding—than Cotton Pershall. This book was a command performance, because thousands of dog owners and trainers requested that Pershall’s methods be set down for generations to follow. Through the eyes and words of professional trainer Bobby N. George, Jr. that’s exactly what happened.

The book includes complete techniques and training guidelines for lining, marking, obedience training, play training, handling doubles and triples easily, land and water retrieving, the forced retrieve, techniques to make your dog a more effective waterfowl retriever, and starting puppies through finishing a dog—as well as fifty years of reminiscences about dogs, trainers, waterfowl hunts, and field trials. Buy Now