A close encounter with a huge grizzly or brown bear can be an unforgettable experience—if you survive to remember it.

Come the end of September, there are few places I’d rather be than in Last Chance, Idaho, so named because enlightened lodge owners incorporated a 500-foot wide, 33-mile-long strip of U.S. 20 in 1947 so they could serve liquor by the drink in otherwise dry Fremont County. Booze isn’t the reason for my affection for this, the narrowest town with the longest main street in the world. Here, Henry’s Fork swings within a double-haul of the highway, and its rainbows seem almost insatiable on their final feed before winter.

The river cuts through Henry’s Fork Caldera, the collapsed and nearly level floor of an ancient volcano created by the same magmatic hotspot that later birthed Yellowstone National Park. Broken and jagged, the rim of the caldera rises a thousand feet above the basin floor. When temperatures turn frigid, rutting elk come down from the high parks where they’ve grazed since spring. Following them are grizzlies, which like trout, have set out to stoke up on fats to tide them through the winter.

Standing in TroutHunter, a Last Chance lodge-cum-fly shop, I was booking a float when I overheard that co-owner Rich Paini had just been mauled by a grizzly. Later I learned the story. Rich and his partner Jon Stiehl had left Rich’s house, more or less across the road, about 6 a.m. with their bows to hunt elk. Following a powerline, they’d crept across the caldera, a patchwork of weedy meadows broken by stands of aspen and lodgepole pine.

After a couple of hours and seeing nothing but a solitary grouse, they plopped down on a log, savored a cup of coffee, and deciding nothing was to be gained by hunting further, headed back toward the shop. Poking down a game trail, they heard what they thought was an elk blundering through the brush. Jon moved toward the commotion, putting a small stand of aspen between him and Rich. A moment later he heard Rich yell, “Bear!”

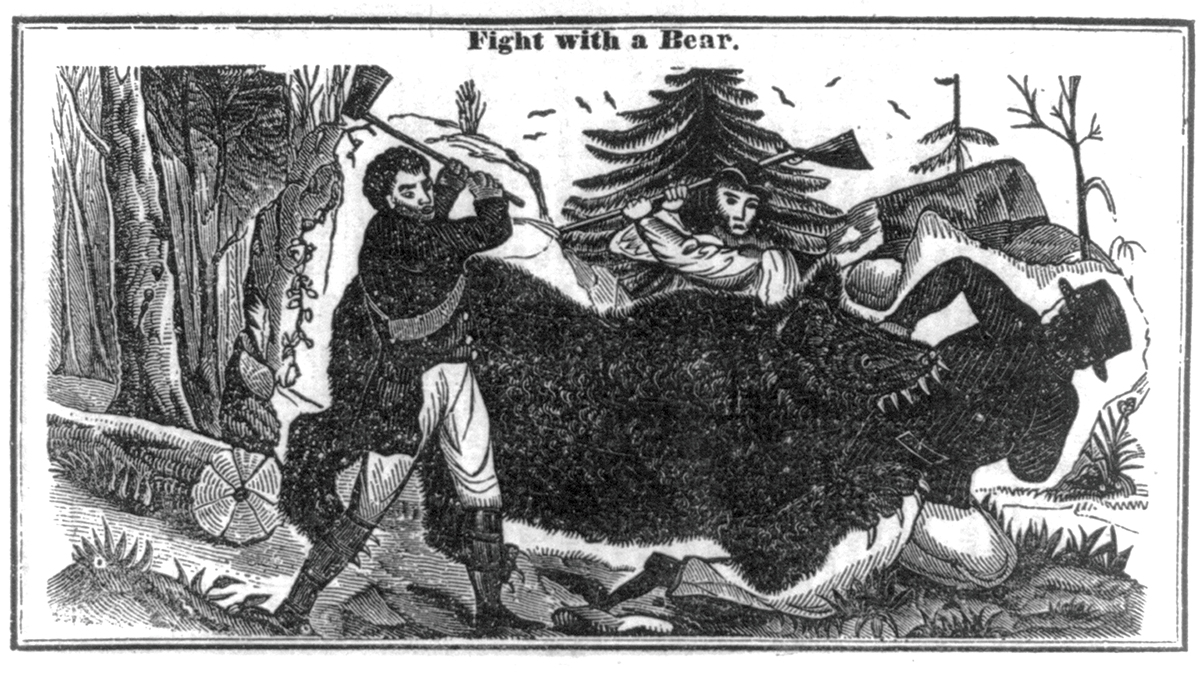

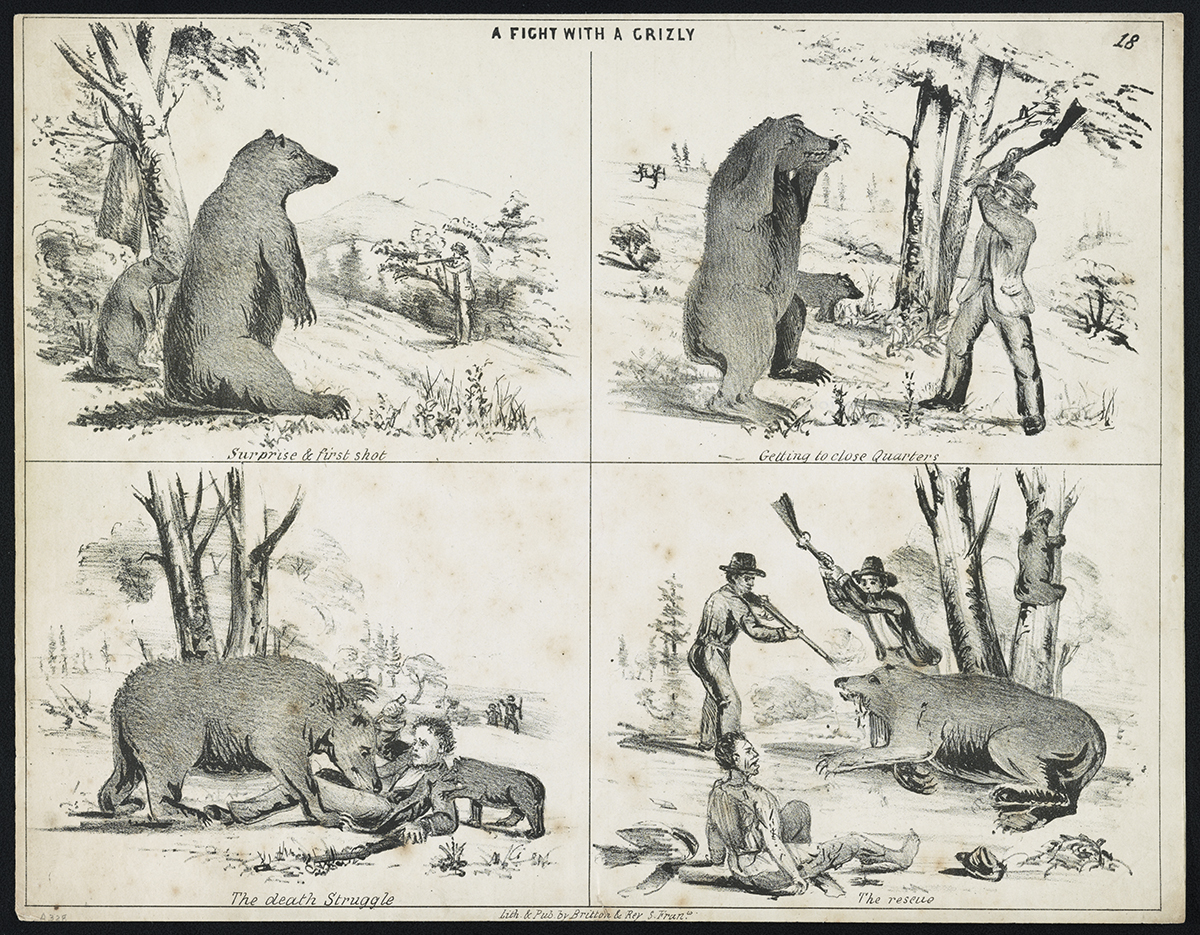

Grizzlies are the most aggressive of North America’s bear species . . . Surprise a bear or any other big predator at close quarters, and you may be in trouble.

Rich came barreling out of the brush followed by a grizzly ready to pounce. To protect his face, he threw up his right arm. Growling, the bear bit down on it. They tumbled to the ground as Jon unsheathed his pepper spray. With his left hand, Rich thrust his bow at the bear’s head. With another ferocious bite, the bear crunched down on his hand and shattered the arrows on the bow quiver. Into the melee, Jon fired his pepper spray “up the bear’s ass,” as he remembers. The bear raced off into the woods.

The attack lasted less than 30 seconds. Rich’s arm was broken, and the bear had bitten off his ring finger. Jon picked it up from the dirt. A call to 911 brought two rangers from nearby Harriman State Park. They loaded Rich into the vehicle and sped down a dirt road toward his house, where an ambulance would be waiting. Alas, the road was barred by a locked Forest Service gate. Ramming through it shattered the vehicle’s windshield. Minutes later Rich and his wife were in the ambulance screaming down the highway toward Ashton, from which Rich was airlifted to a hospital.

Today, Rich’s arm is completely healed, and his wife wears his wedding ring—and a bit of the finger bone—on a gold chain around her neck. It’s their lucky charm. He and Jon had startled a sleeping grizzly satiated after feeding on a dead calf. After such a traumatic encounter, you’d expect Rich to carry a grudge against grizzlies. Not so.

What gets his goat, though, are visitors who refuse to become “bear aware.” Starved from their long winter fasts in dens high on ridge flanks, grizzlies head for grasslands around Last Chance in search of winter-killed cattle and other large mammals. Males prowl an average of 330 square miles, three times farther than sows, in search of food. They’ll eat new green vegetation and, of course, berries and their buds. For grizzlies living near Yellowstone Lake, spawning cutthroat trout are an important source of protein and fat. Wise anglers carry bear spray.

Spring also brings the first waves of tourists to Last Chance and a growing abundance of garbage. It’s not uncommon for someone who rents a cabin for the summer to put out dog food in hopes of getting a photo of a big bear to send to friends and family back home. Grizzlies are easily enticed to human food.

“Once a bear learns a bad practice,” says Idaho Fish and Game biologist Gregg Losinski, “it’s over. There’s a good possibility that we’ll have to put it down.”

Unfortunately, attacks by grizzlies in Island Park have become more common since Rich was mauled six years ago. They now occur once or twice a year. The same is true in the area around Yellowstone, though fatalities are rare. Like Rich, many of the victims are bowhunters who surprise bears while sneaking quietly along, hunting into the wind.

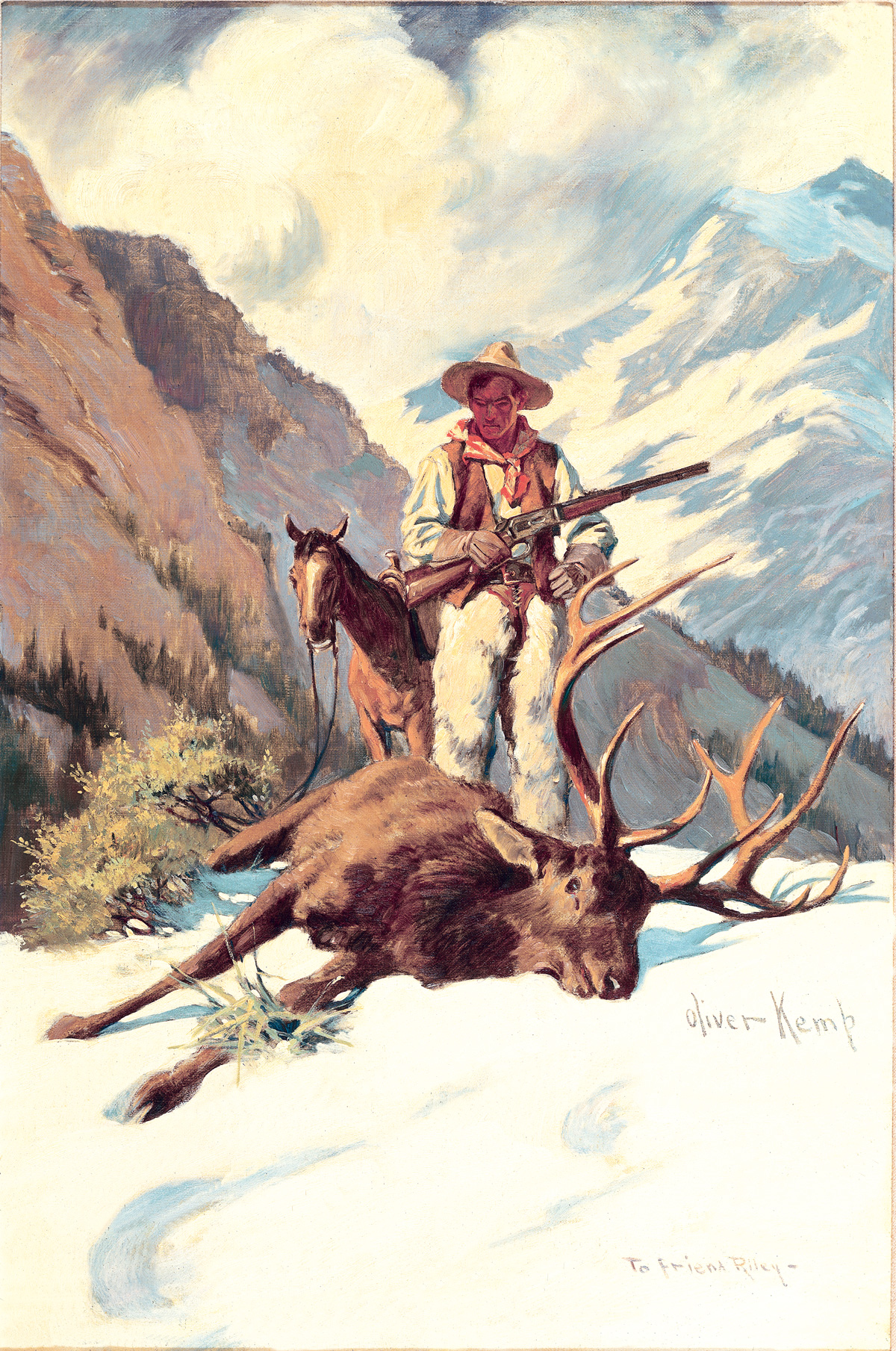

Two mature bears engage in a territorial battle. Opposite: A successful hunter with his trophy while hunting on the Kodiak Archipelago.

Rich was in the wrong place at the wrong time but had no way of knowing it. Neither did Rick Sitts and his daughter Laura, who were hiking on the rim of the caldera and helping a ranger monitor the habitat of a sow when she bolted from an all but impenetrable blowdown, flattened the ranger like a linebacker sacking a quarterback, and vanished before they even had time to use their bear spray. The ranger, it turned out, was not badly injured.

In retrospect, the pair said they should have realized a bear kill was nearby when they passed a bevy of ravens that failed to fly off. Now they know how foolhardy it is to enter a patch of cover where you cannot see ten feet ahead. Since the bear was upon them in seconds, they also learned there was no time to decide whether to shout, back away, or roll onto the ground and play dead.

Two years later the boar that mauled Rich attacked another forest researcher near Last Chance. That bear was actually well known to biologists. He was first collared in June 2007, weighed 260 pounds, and was 4 years old. Captured two months later, he’d put on 60 more pounds, roughly one pound per day. Corralled again a year later, he’d reached 361 pounds. A year before he mauled Rich, he’d grown to 625 pounds, more than double his weight when first collared.

Grizzlies are the most aggressive of North America’s bear species, says Stephen F. Stringham, Ph. D., president of WildWatch. He’s spent more than 30 years studying their behavior. No bears are inherently hostile, he points out, but they can be violently defensive. About 70 percent of maulings or fatalities are the result of grizzlies defending their cubs, and ten percent occur when they’re defending their kills, as happened to Rich. Surprise a bear or any other big predator at close quarters, and you may be in trouble.

The world’s bears belong to the family Ursidae, which evolved millions of years ago in semi-forested regions. To escape predators, they developed the ability to climb trees. As time progressed, brown bears (Ursus arctos) became adapted to life on treeless steppe and tundra. With no place to hide, they had to learn to battle saber-toothed cats, 11-foot-tall short-faced bears, and other long-extinct predators of the last ice age. Black bears (Ursus arctos americanus) retained the ability to climb trees and, because they can escape trouble, gained the reputation of being less confrontational than browns or grizzlies (Ursus arctos horribilis).

In comparison to black bears, which arrived in North America 3.5 million years ago, brown bears and grizzlies are relative newcomers. Beginning about 70,000 years ago, brown bears arrived in North America after migrating across Beringia, the land bridge that joined Alaska and Siberia when glaciers were at their maximum and sea levels at their lowest. Fifty thousand years later browns that had adapted to feeding on salmon started filtering down the coast, while grizzlies foraged inland and southward through the Rockies. Once present in northern Mexico, the area around Yellowstone National Park pretty much marks the southern terminus of the grizzly’s range today.

Coastal browns crossed what is now the Shelikof Strait onto Kodiak Island and became genetically isolated about 12,000 years ago when glacial melting caused sea levels to rise. These bears evolved into a genetically distinct breed—(Ursus arctos middendorffi)—which is named after its host island.

According to Alaska Game and Fish, Kodiak’s bears are the largest in the world. On hind legs they can tower nearly ten feet. The biggest males weigh in at more than 1,500 pounds, and large females, 1,000 pounds. Males come out of their dens in late April, though sows with cubs don’t emerge until June. Kodiak Island now boasts one of the highest bear population densities in the world—roughly 3,500, or seven bruins for every ten square miles.

Coastal bears forage along the shore searching for seals, moose, or deer carcasses. In June salmon begin to run, and bears begin to concentrate on them. Inland bears search for the greatest source of fats and protein they can find. Young-of-the-year calves and injured adult mammals are favored prey.

The odds of bagging a huge brown bear may be best on Kodiak Island or down on the Alaskan Peninsula stretching out toward the Aleutians. That’s where Roy Lindsley killed his monster brown bear, which measures 3012/16 inches, a record that has stood since 1952. Lindsley’s record, incidentally, was almost eclipsed in 2006 when 9-year-old Fern Spaulding-Rivers dispatched a behemoth that scored 291/16 inches. She shot it with her 375 H&H and her own handloads to boot!

Not to be overlooked are grizzlies of the interior. Bowhunter Larry Fitzgerald was hunting moose outside of Fairbanks in September 2013 when he spotted a big bear. After stalking it for three hours, he killed it with a single neck shot from 20 yards. Fully stretched, the grizzly measured nine feet, and its skull scored 276/16 inches. That’s only a half-inch smaller than Boone & Crockett’s world record, a skull found in 1976 on Lone Mountain on the Alaskan Peninsula.

Each year hunters kill about 1,000 of Alaska’s estimated 30,000 grizzlies and browns, and another 500 or so are legally harvested in British Columbia and the Yukon Territory.

During the spring brown bear season, April 1 through May 15, hunters do best cruising and spotting from a boat just beyond the coast, then going ashore when a trophy is sighted. Others choose to sit and scan likely looking hillsides before making their stalks. The fall season runs from October 25 to November 30. Spring hunts tend to produce bigger bears—and more of them—though bears in autumn usually have more lustrous coats.

Predator calls can be very effective in attracting hungry bears. While on assignment to test a new rifle, I was sitting with my guide on the nose of a mountain overlooking Alaska’s Selawik National Wildlife Refuge, glassing the tundra 1,500 feet below us for barren-ground caribou. We’d hoped that a string of the Western Arctic caribou herd would funnel up the draw in front of us. Across the tundra we spotted a silvery lump, which the guide identified as a grizzly. I asked if he could call him closer.

Since my rifle was a 280 Ackley Improved loaded with 140-grain bullets, completely ill-suited for grizzlies, all I wanted was to get some photos. The guide issued forth mournful bleats like those from a distressed calf. The bear turned, stood tall showing his charcoal- grey belly, and began lumbering toward us… .

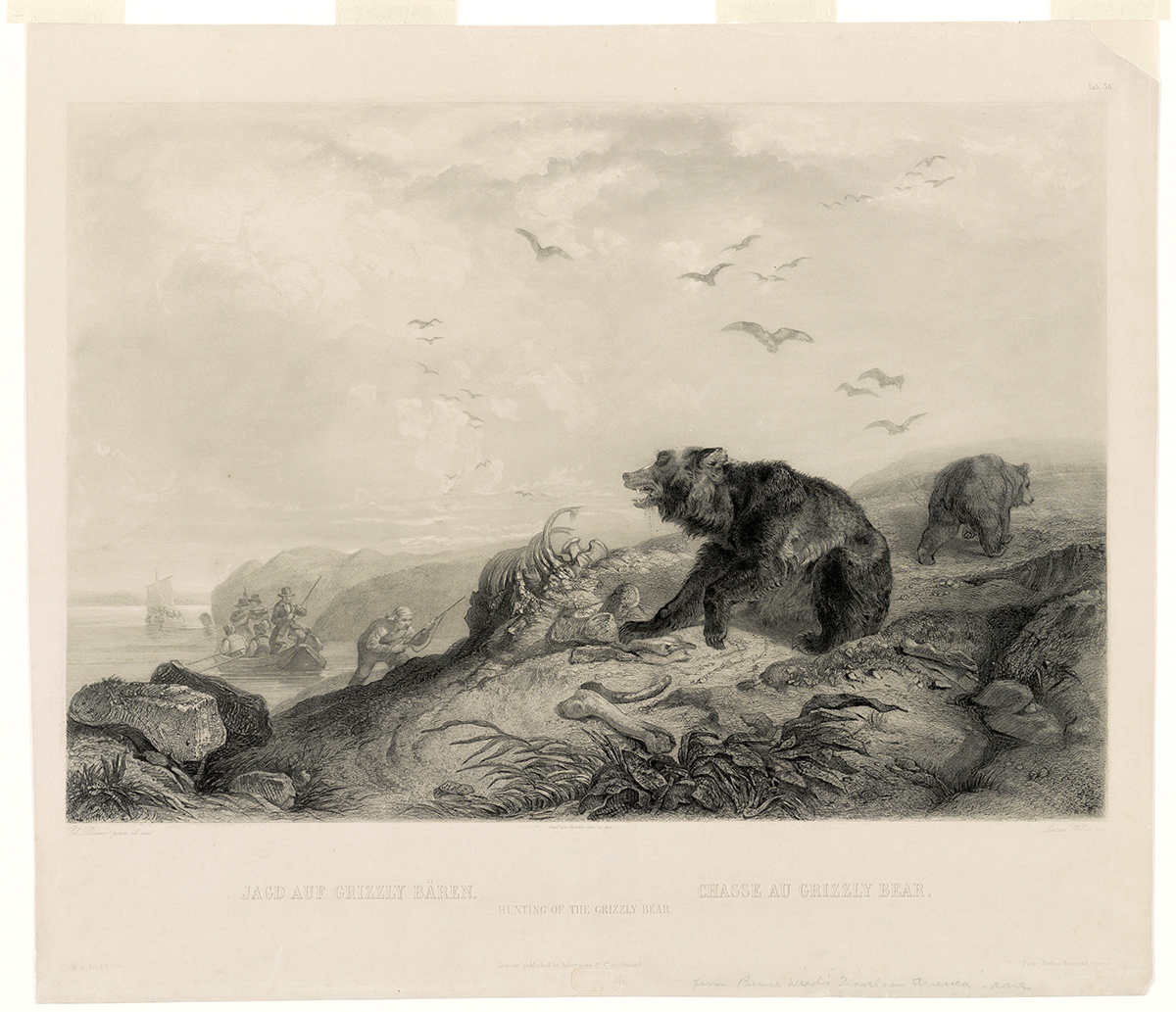

Hunting of the Grizzly Bear by Lucas Webe

In the early 1800s, when Lewis and Clark explored the West, an estimated 50,000 grizzlies roamed the land. By 1975, when they were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, their numbers in Yellowstone National Park and the surrounding area had dwindled to 136. According to Kerry Gunther, a bear management biologist at Yellowstone Park, 690 grizzlies inhabit the region, down from 717 a couple of years ago. He attributes the decline to hunters who killed grizzlies in self-defense or by accident, thinking they were legal black bears.

But that’s a conservative estimate, says Losinski, who along with other biologists believe the grizzly population may be closer to 1,000. He reports that they’re spreading into habitat they once occupied 100 miles east of the Rocky Mountain front in central Montana. Among the reasons for this, according to Stringham and former Yellowstone bear biologist David Mattson, may be nothing more than a decline in foods like whitebark pine nuts within the park’s ecosystem. Tiny populations are also thought to exist in Idaho’s Selkirk mountain range and Washington’s Cascades.

Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke hailed the recovery of grizzlies in the Yellowstone ecosystem as one of “America’s greatest conservation successes” and delisted them as an endangered species.

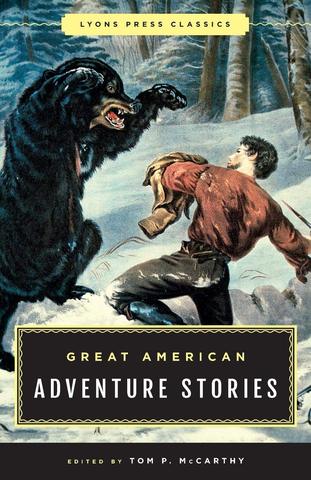

An extraordinary collection of fifteen stories that celebrate America’s unquenchable thirst for excitement.

Great American Adventure Stories contains page-turning accounts of the Galveston Hurricane, the Alaska Gold Rush, a robbery featuring Jesse James, an eyewitness account of the Johnstown flood, and much more. For a taste of the American frontier, Daniel Boone and famed scout Kit Carson depict what they saw and experienced as the country expanded and blossomed in the West. These accounts all have one thing in common: They capture the grit and spirit of people who made America what it is today.

Created for adventure addicts there has never been a more exciting collection of stories that celebrate the indomitable spirit of the American character. Buy Now