I was suddenly awash in pale blue phosphorescence and I briefly reckoned poor ventilated Private Quigley had his chilly arms around me!

Right turn at Frogmore, south down a dozen miles of two–lane island blacktop, through woods and swamps and fields, to old Fort Fremont at Land’s End. Fort Fremont was too late for the Spanish American War and too early for WWI and the only shooting there was between drunken artillerymen and equally drunken Negroes. Freemont stood and still stands, abandoned and overgrown, a concrete monument to a war that never came. But more of that later.

That’s St. Helena Island, South Carolina. If it wasn’t heaven, it was close back when I was a boy. Sweet salty oysters free for the picking, sea trout, spot-tails, puppy drum or flounder, something was always on the bite. We kept the freezer full.

You could jump deer in the saw palmetto fans. Hogs busted out, ran wild and could be hunted. Wood ducks wheeled and whistled in blackwater ponds, droves of doves fluttered in the picked-over corn and wheat, nearly every island shanty had a half-tame covey of bobwhite quail hanging around the pea patch or blackberry thicket and paper low–brass number eights were ten cents a shell. You could kick up cottontails anytime you wanted. And oh, did those paper shells smell so good.

But eventually romance budded and budding small–town romance required considerable creativity. There was the Breeze Theater in downtown Beaufort and the Greenlawn Drive-in on the edge of town, decried from the First Holiness pulpit to the Church of God to the Garden Club as a passion pit and the gateway to Hell. And halfway between the indoor theater and the outdoor one, there was curb-service at the Shack where the boss sat in a tower above the kitchen and kept close eye on the tailfin jungle, always alert for fistfights and somewhat less intently, for fornication.

Just flash your headlights. Pizza, burgers, Cokes and fries on demand, condoms too, if you asked privately. Cash makes no enemies, let’s be friends.

Dixie Deluxe, three for a quarter, with crossed Confederate flags on the label and the hopeful motto, “The South Shall Rise Again.” And I am here to testify, it did, a time or three.

Let me tell you about it.

Patrons felt obliged to squall tires when leaving. If you were driving your momma’s ’62 Falcon Ford six, your buddies might gather round, lift the ass–end of the car while you revved the engine. A squawk and a bark as the poor tires bit amid laughter and applause as you peeled out onto US–21.

And over on St. Helena, there was the Ghost Light on the Land’s End Road, our version of watching submarine races. “Hey baby, want to go look for the Ghost Light?” Holiness Baptists believed in ghosts. The Church of God did too, the Garden Club refrained from comment.

There was a four or five mile stretch of unusually straight highway, then a monumental oak where the road hooked north toward the old fort. Any given Saturday night, there might be a dozen cars beneath that oak, local swains with les dames du noir, a polite French approximation for gals who might shuck their britches.

Ghost light, a puzzlement. In Europe it’s “Will-of-the-Wisp.” In Appalachia, “Fox Fire.” Here on the coast, “Jack-mulatter,” most certainly connected to “Jack-o’-Lantern.” Scientists have pondered a thousand years. They even gave it a Latin name, Ignit Fatuus, literally “fool’s ignition.”

Whatever you might call it, the Land’s End Light appeared infrequently, though many claimed to have seen it. There were various explanations of the phenomenon. Our science teacher advanced some complicated atmospheric analysis, wherein occasional and unusual temperature inversions refracted headlights from another highway miles away and made them appear on the Land’s End Road.

Fort Fremont was too late for the Spanish American War and too early for World War I.

But a woman testified it chased her car and made the engine skip and backfire, her hair stand up, so it must be electrical like ball lightning. Some said it was a Confederate soldier who got his head cut clean off by a Yankee cannonball during the Battle of Port Royal Sound, and he wanders eternally with a lantern in search of it. Yet others got more specific. It was the ghost of one Private Frank Quigley, stationed at Fort Freemont in the early 1900’s, who took a load of buckshot on that same road, for his fondness for brown girls and white whiskey.

Ignit fatuus? And then three boys decided to ignite some serious foolishness.

Me and Eddie and Jim, the usual suspects. We had Eddie’s 1956 Packard Clipper, beloved by moonshiners for its phone-booth trunk and level ride suspension. No matter how many cases of Ball jars you loaded up, the Clipper always looked like it was running empty. Jim had a kerosene lantern. I had a gunny sack.

It seemed like a good idea at the time.

Eddie drove down to the crowd beneath the oak, 15 or 20 classmates and their dates, offered greetings and polite inquiries. Nobody had seen nothing yet. Then, he proceeded to lube them up with some lie, I disremember exactly, some reason or the other why I had to be home early but promised to come back and wait out the rest of the evening with them.

The crowd thus greased, Eddie dropped the Packard in gear and proceeded down the road a mile or more before stopping with his emergency brake so his brake lights would not alert the assemblage to our shenanigans. Jim clapped his hat over the dome light as I opened the door and slipped into the swamp, lantern, gunny sack and flashlight in hand. I sat on a stump, 30 or 40 minutes until Eddie came back and joined the seekers after the light. Then I fired the lantern, wrapped it in the sack, walked to the middle of the road, cast the sack aside.

Down under the oak there was a collective shriek, a flip-flop flapping stampede and a great rattling of door-locks as the girls fled to the presumed safety of the automobiles. I swung the lantern side to side. “Look, it’s zipp-zipping back and forth across the road!” I lowered it to my ankles, raised it above my head. “Damn, it’s jumping thirty feet into the air!” Ah, the mind is a terrible thing to waste.

Of course, I couldn’t know any of that yet, walking down the middle of that St. Helena Island two-lane blacktop like a damn fool, lantern in one hand and skeeters in my ears, but Eddie and Jim gave a full and spirited report later.

Suddenly headlights, one pair in each lane, coming at me at 60 miles an hour, a mile a minute, 88 feet per second. I had to get my fool ass off that road quick. I shut off the lantern, dove for the ditch, lay on my belly on moist earth as the cars thundered by.

And then: “Great Gawd-A’mighty, the haints done got me!”

I was suddenly awash in pale blue phosphorescence and I briefly reckoned poor ventilated Private Quigley had his chilly arms around me! I flicked the flashlight with a trembling hand. That glowing glob at my elbow was nothing but a mushroom, that pillar of cold fire at my feet was a rotting oak stump. The flashes around my belly were sweet gum leaves. The woods were lit up as far as I could see.

I tried to make sense of it while awaiting the Packard. So, the blacktop, heated by the afternoon sun, created a gentle updraft that brought the phosphorescence from the cooling swamps where it congealed and collected into a glowing orb that scared the Be-Jesus out of believer and skeptic alike? Or something like that. Made more sense than temperature inversions and refracted headlights.

My buddies didn’t think much of my theory but never offered any of their own. And 50-odd years later, the faithful still gather beneath that big oak waiting for the Land’s End Light.

Me and Eddie and Jim laughed about it plenty amongst ourselves.

All these years I have kept mum, mostly.

But now I am telling you,

And I hope I got somebody laid that night.

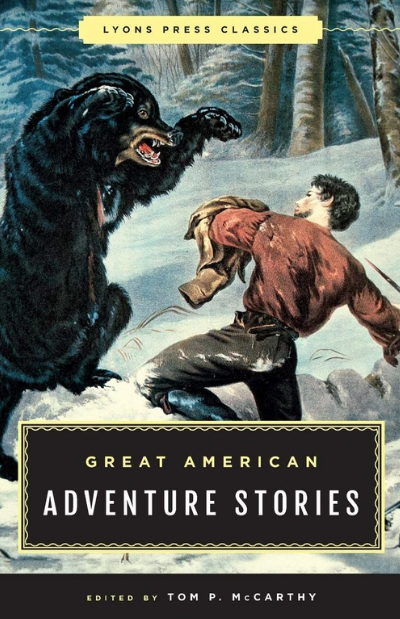

An extraordinary collection of fifteen stories that celebrate America’s unquenchable thirst for excitement. Great American Adventure Stories contains page-turning accounts of the Galveston Hurricane, the Alaska Gold Rush, a robbery featuring Jesse James, an eyewitness account of the Johnstown flood, and much more. For a taste of the American frontier, Daniel Boone and famed scout Kit Carson depict what they saw and experienced as the country expanded and blossomed in the West. These accounts all have one thing in common: They capture the grit and spirit of people who made America what it is today.

An extraordinary collection of fifteen stories that celebrate America’s unquenchable thirst for excitement. Great American Adventure Stories contains page-turning accounts of the Galveston Hurricane, the Alaska Gold Rush, a robbery featuring Jesse James, an eyewitness account of the Johnstown flood, and much more. For a taste of the American frontier, Daniel Boone and famed scout Kit Carson depict what they saw and experienced as the country expanded and blossomed in the West. These accounts all have one thing in common: They capture the grit and spirit of people who made America what it is today.

Created for adventure addicts there has never been a more exciting collection of stories that celebrate the indomitable spirit of the American character. Buy Now