I take my time with the old men now.

I take my time with the duffers I find on opening day, swapping yarns and a thermos by 9am, or posted alone on a barren ridge no deer has crossed in more than a decade. They will tell me, whether I ask or not, that they don’t much care if they kill a buck, and if my patience holds, they may relate some windy story of so-and-so bagging such-and-such upon that very spot, describing in vast detail the weather and game and all the events of a distant morning. They like to be out, they say, just out in the woods, and they spend these hours in a reverie of familiar friends and places.

So I see them not as the poorest hunters, nor as quaint, nostalgic fools. Because now I am almost one of them, and if I don’t know why this happened, at least I have an idea when.

It began in the glare of a flashlight beam, searching for signposts of tree and stone that led to the oak, which would be my home for the next few hours. I scrambled aloft, hoisting the bow up after me and settled back to wait as booming owls slowly bent to the first jay calls and chattering squirrels.

There were two bucks here I had seen off and on for a month: a wide-racked eight that I wanted badly and a slim fork-horn I would probably take just the same. And on this morning, it was the smaller buck who gave himself to me, the way it is said deer will if you hunt with a certain measure of respect.

There were two bucks here I had seen off and on for a month: a wide-racked eight that I wanted badly and a slim fork-horn I would probably take just the same. And on this morning, it was the smaller buck who gave himself to me, the way it is said deer will if you hunt with a certain measure of respect.

He slipped from the thicket, pausing to study with broad-cupped ears and eyes and nose for a hint of danger. He may have found it, but in the floodtide of the rutting moon he could not wait long and started forward, each step in the frosted leaves like a pistol shot. I watched his head, where you would see if anything were amiss until it passed beyond the bole of a maple, drawing the bow as here appeared, now locked and focused on a patch of hide no bigger than my fist. The arrow flickered away to bloom for an instant in that patch of hide, the buck bounding off incurving arcs that led from the clearing and through the thicket beyond.

The hardest part of bowhunting is this: the long wait as the arrow performs its work — an hour’s patience that makes the difference between game found and game forever lost. I let the first few moments pass while my hands ceased trembling and my heart resumed some sense of rhythm, recalling where the buck had walked and the last sound of his flight. Then I made my way quietly back to the pickup waiting like a patient steed at the roadside.

I drove to a small cafe where men in John Deere caps and overalls came and went, ordered eggs and bacon that I ate but never tasted, read the morning paper front to back without absorbing a single word, and glanced at the big wall clock 60 times in as many minutes. And when I was sure there was nothing that time could mend, I paid my bill and left.

I found the arrow first, buried in the soft loam, the fletchings stiff with drying crimson. At the clearing’s edge were the deep impressions of the buck’s hooves and the start of a blood trail that began well and got better. I could have followed at a trot. but I held to a cautious crawl. and a hundred yards later came upon the buck stretched in the yellow grass. He seemed enormous, as they always do, since there is some strange magic in killing with the bow; something vaguely miraculous in the act itself I studied the mark where the shaft had entered, behind his shoulder a hands-breadth below the spine, then rolled the buck to see the exit, knowing the arrow had cut both lungs — a wound beyond which you or I would never manage a single step.

Drawing my knife, I set to work and had almost finished when three deer boiled from the thicket in a clatter of snapping brush. The doe and her yearlings slammed to a halt. confusion plain on the doe’s face as she struck the odors of man and blood. Then from the woods beyond I heard the coarse grunt of what could only be the eight-point buck. On another day I might have cursed myself for this chance I had missed, but my mind had wandered as I worked toother deer and other days; deer killed or not, coveted perhaps or only glimpsed, to other chances come and gone. So with thoughts peopled by remembered deer, with the deer of the present still under my hands and the deer of the future calling from the wood, I could not say that one or the other had any more weight or importance. Like kinder versions of Dickens’ ghosts, they were stages on a journey where looking back was now as pleasurable as gazing forward and the miles that lay ahead were in no way finer or more alluring than those already traveled.

Drawing my knife, I set to work and had almost finished when three deer boiled from the thicket in a clatter of snapping brush. The doe and her yearlings slammed to a halt. confusion plain on the doe’s face as she struck the odors of man and blood. Then from the woods beyond I heard the coarse grunt of what could only be the eight-point buck. On another day I might have cursed myself for this chance I had missed, but my mind had wandered as I worked toother deer and other days; deer killed or not, coveted perhaps or only glimpsed, to other chances come and gone. So with thoughts peopled by remembered deer, with the deer of the present still under my hands and the deer of the future calling from the wood, I could not say that one or the other had any more weight or importance. Like kinder versions of Dickens’ ghosts, they were stages on a journey where looking back was now as pleasurable as gazing forward and the miles that lay ahead were in no way finer or more alluring than those already traveled.

The does began to move, slow and stiff-legged at first, finally bursting into graceful flight, and I heard the buck chase after them. Then silence again, and the bell-notes of sparrows in the grass. So this year I told my wife that I didn’t care all that much if I killed a buck or not Barbara was less surprised by this than I, having taken her share of deer and possessing a woman’s grasp of emotions that might seem strange and incongruous to me.

In a few weeks when the season opens, I may ignore the horn-scarred saplings, the scrapes and beaten trails, and travel up the mountains where that first deer gave itself to me so many years past, I will lean against the same tree, rest a battered quiver on the same moss-shrouded stone, not in hope that history will repeat itself but only to savor the wine of memory. And if some boy should come my way with a shiny bow and a head full of dreams, I will wave to him and let him go. I will not bother to relate the tale of so-and-so killing such-and-such upon that very spot Because I am not truly one of the old men yet.

But I’m getting there.

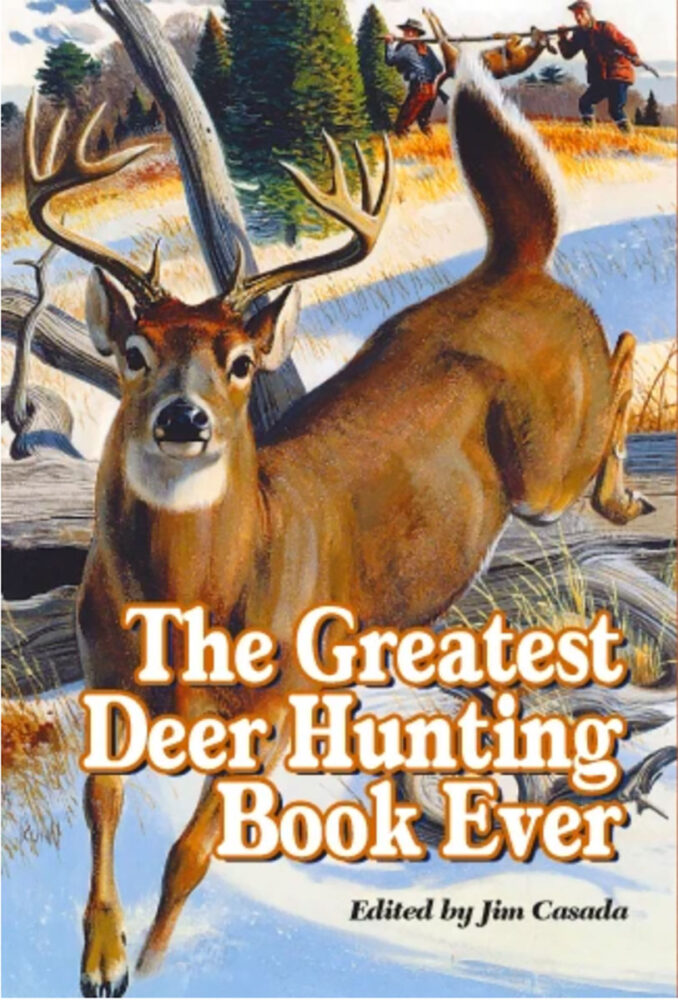

On these pages is a stellar lineup featuring some of the greatest names in American sporting letters. There’s Nobel and Pulitzer prize-winning William Faulkner, the incomparable Robert Ruark in company with his “Old Man,” Archibald Rutledge, perhaps our most prolific teller of whitetail tales, genial Gene Hill, legendary Jack O’Connor,Gordon MacQuarrie and many others.

On these pages is a stellar lineup featuring some of the greatest names in American sporting letters. There’s Nobel and Pulitzer prize-winning William Faulkner, the incomparable Robert Ruark in company with his “Old Man,” Archibald Rutledge, perhaps our most prolific teller of whitetail tales, genial Gene Hill, legendary Jack O’Connor,Gordon MacQuarrie and many others.

Altogether, these carefully chosen selections from the finest writings of a panoply of sporting scribes open wide the door to reading wonder. As you read their works you’ll chuckle, feel a catch in your throat or a tear in your eye, and venture vicariously afield with men and women who instinctively know how to take readers to the setting of their story. Buy Now