Born in a small shop behind William Mason’s home, Gertrude the decoy would live a life most fulfilling. Here are a few of the many stories she has to tell.

Hello, my name is Gertrude. I was named after Bob’s Aunt Gertrude Reade, a woman with a special gleam in her eye. In family legend, that look charmed several husbands and lovers. I’m a decoy, a Mason Brant, and my saucy look has charmed and lured many birds into the range of my owners’ shotguns.

I was born in Detroit, Michigan in 1903 at the Mason Decoy Factory. The word factory today implies a workforce of hundreds, if not thousands. Well, this factory was the backyard and small shop behind William Mason’s home. Some of my relatives with whom I’ve hunted tell me that Bill’s sons expanded his operation into a two-story building a couple of years later.

I was born when the Mason operation was small. Bill picked me out when I was just a cedar block, turned my body on the lathe, carved my head and passed me on to George who painted me with thick swirling patterns that imitated the feathers of a Brant. Then I, along with five sisters and brothers, was wrapped in newspaper and straw and placed in a wooden box. Railway Express delivered me to Cape Cod.

In Chatham I joined the hunting rig of Ben Browne, a dedicated waterfowler, a man who hunted every day the birds were “in,” and was on the water scouting when they were not. I was set out in the salt water and proudly rode the waves surrounded by my brethren. And off to my downwind side Ben always placed a flock of live decoys – a dozen Canada Geese whose calling and movement gave life to the rig of wooden decoys. My saucy look and the sweet sounds of the geese brought birds into the rig. Then the guns barked and big dogs – Chessies and Labs – were sent after the valuable dead and wounded birds. Ben shipped his birds in wooden kegs to the game markets in Boston.

Ben wore ragged wool, an old pair of patched coveralls and oilskins when he hunted. He used a Winchester 10-gauge lever action shotgun, and he could make the lead fly. His clothes were worn and dirty, but Ben knew how to care for his gun, dogs, boat and decoys. I was well kept and happy.

A few years later Ben was out of business. Market hunting was now illegal and the law – at least in Massachusetts – was enforced. Ben went back to the cranberry bogs, and my cohorts and I were traded to Guy Wentworth for some tools and other considerations. Guy and his friends were something new in my experience. They all had jobs in Boston and came to the Cape for days at a time to hunt and fish. They obeyed the gunning laws and bag limits. And for them a good day did not necessarily mean a full bag.

They prized Atlantic Brant, and out in the Eelgrass my confident look still worked. They liked me and I liked them. But they used Goldens to retrieve the birds. Those dogs were beautiful but dumb. At least once a hunt Lucy or Toby got tangled in my line and dragged me into other decoys or onto the rough shore. This cut me up and dented me.

Guy shot a Parker DHE; his friends used L. C. Smiths and Ithacas. They wore tweeds and neckties under their English hunting coats. There were often friendly discussions after the hunt between the Smith and Parker shooters as to which gun was the most responsive. The Ithaca shooters kept quiet.

That Parker DHE was an arrogant gun – “Old Reliable” to hear her tell it. Ha. The Smiths and Ithacas were pretty regular guys who talked to all the decoys. Old Reliable only talked to Crowells.

After every hunt Guy wiped me down and washed off the salt and grit. And at the end of the season he stored me in the dry rafters of a barn. Lots of birds, lots of fun, then a long rest. This went on for fifteen years, and then a fall came when no one showed up. The next year the same. And again. The years passed. The dust and grit grew on me in layers. I made friends with some mice and they chewed off my decoy line. It got cold, then hot. I dried. My paint flaked. I cracked.

Finally, a day came when there was movement in the barn. Two men opened the doors and let in the light. They looked up.

“By god, Geoff, look up there. The rafters are full of tollers. Must’ve been put there before the war. Let’s bring ‘em down.”

Sounds of clumsy movement and then a pair of heavy hands on me. I was brought down into the light near the door. Water and rags were applied. I was carefully cleaned, wiped dry and placed outside against the barn wall. More decoys joined me. And more. Nearly fifty of us in all. Six brant. A dozen geese. Thirty duck – the majority were black ducks but a few were mergansers and buffleheads. The two men picked us up. Stroked us. Looked carefully at our front, back, sides and bottom. Made comments about paint and workmanship.

“Look, that’s a Crowell. And here’s another. Look at that bufflehead. He sure knew how to paint. Those’re Lincoln geese; they all have the split. Got some unknowns over here but look at that – it’s a Boyd merganser. My goodness, those Masons’re worn but they have the original paint. I wonder whose rig this was. Whoever he was, he sure chose well. None of these are pristine, but they’re all good and original with honest hunting wear.”

They flipped a coin. Russ had first pick; he chose a Crowell. Then Geoff and another Crowell. Back and forth it went. I went to Russ. He wrapped me in burlap and placed me carefully in the back seat of his car. Other decoys were piled all around me. As we were packed some side deals were made.

“Russ, I’ll trade you two Lincolns for that Boyd mergy. Your choice of which two.” And the dealing continued. I and two of my fellow Masons were traded to Geoff for a Burr shorebird from Geoff’s collection.

Collection? Hold on now; there’s a new word. I learned that “collection” meant no more hunting, but with luck a place on a shelf with other birds and caring hands to pick me up and admire me. And now – two auctions and three owners later – that is where I am – in Bob’s collection. I live on the bookcase next to the woodstove in the great room, and with my little eyes I spy other birds on nearby shelves and hanging from the walls. Bob and Joanne speak of Crowell, Perdew, Lincoln, Boyd, the Wards, Benson and Clark, but their eyes keep coming back to meet my happy ones. Joanne named me “Gertrude”; I answer to that name and am proud I rest on my perch.

(A pause here as Gertrude takes a deep breath and knocks back a whiskey)

Well, I thought I was finished; my tale done. But I hear murmurs. I see Granthia’s arm edging up in the air, Charlie’s hand twitching and Joe shifting his weight. Bob’s told me about you guys. God knows what Joe and Webster and Zinsser will do about my spelling and punctuation. I didn’t go to Harvard like Guy or Dartmouth like his Ithaca-shooting friend. I’m a decoy – paragraphing. Ha. But most of the noise seems to be about auctions. I thought I cut that section a little short. I’ll tell you about my first one in 1970. Here goes:

Geoff’s heirs consigned me and many of my friends and relatives to The Richard Bourne Auction house in Hyannis. I was unpacked, inspected, evaluated, photographed, published and put on a table with my Mason relatives. Other decoys came and more tables were set up. A room the size of a gymnasium was filled with tables and decoys. Many birds from many regions and makers: Crowells and Lincolns from Cape Cod, Ward Brothers from Maryland, Perdews and Ellistons from the Illinois River, Boyds from New Hampshire, Schmidts from Michigan, Wilsons from Maine, Cobbs from Virginia and many birds from Canada. I talked and made friends. I hit it off with another Brant – this one of unknown parentage down from Prince Edward Island, a preener, and boy, was he handsome.

Soon the doors opened and people crowded around the tables. The men and women all knew each other and everyone talked “decoy”: condition, pedigree, previous owner, maker either known or unknown, region and, of course, species of wildfowl.

I noticed two types of decoy collectors. One was more concerned with original, pristine, mellowed paint – a patina, I think they called it – and a wooden surface with no cracks, dents or damage. The other was, as I quickly noticed, a hunter. He was interested in the story the decoy could tell. Each bump and bruise and lost fleck of paint was food for his imagination. Those men pictured me in their rig at dawn as the birds came in and the sleet poured down. I liked them.

The next day the auction began. It went all day. Richard Bourne sold four hundred and fifty birds that day. Dick was fast. His son or uncle or cousin – the auction house was a family affair – brought a bird up; Dick announced the lot number, type of bird, condition and maker and off he’d go. That man could sell. He’d bring down his hammer and go on to the next bird. And they say decoys can’t fly. Well, those birds flew out of there.

The lead-off decoy was a Mason Black-bellied Plover in very good original paint. Dick always started his auctions with a selection of Masons. That plover was pleased to be the first decoy on the auction block and has been getting free drinks from that story ever since. I was well back in the Mason pack because of my worn condition. But I consoled myself with the knowledge that I had hunted, whereas the beautiful pristine birds either had never been near the water or had been used only a few times. The stories I could tell.

And I did tell them – to my new owner and then the next, both hunters. And now I tell them to Bob, next to the fire over good bourbon, as we talk and dream of whistling wings and icy water.

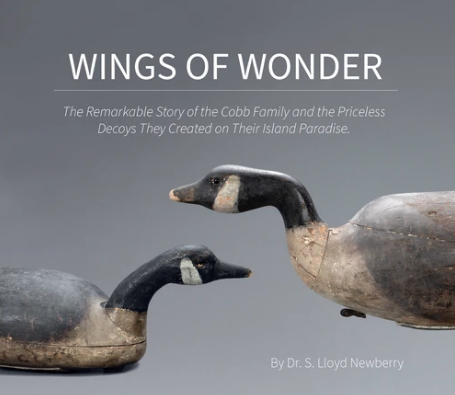

Living in the center of Virginia’s chain of barrier islands, the Cobbs were witness to one of the greatest concentrations of geese, brant, ducks and shorebirds, on the continent. Using that which Mother Nature provided, they developed one of the most outstanding sporting venues in the country, one that would attract guests from far and wide.

Living in the center of Virginia’s chain of barrier islands, the Cobbs were witness to one of the greatest concentrations of geese, brant, ducks and shorebirds, on the continent. Using that which Mother Nature provided, they developed one of the most outstanding sporting venues in the country, one that would attract guests from far and wide.

For their use in hunting, they crafted their own wooden decoys. Though natural and man-made disasters brought an end to their island paradise, these wonderful and highly coveted replicas of the many species they hunted cemented their fame among historians and folk art collectors for centuries to come.

The author traces this fascinating story through three generations of the Cobb family. It’s a chronicle that historians and folk-art collectors will find both educational and enjoyable. Buy Now