They came upon the remains of the buffalo in a thick stand of timber, six hides and heads wrapped in burlap, each strung high from a tree limb to keep it safe from wolves. It was a grim sight, but also a sure sign that they were closing in on their man.

It was mid-March of 1894, still winter in the high country of Wyoming. Felix Burgess, a civilian scout for Yellowstone Park and an army sergeant named Troike, were on the trail of the park’s most elusive and cunning poacher, Edward Howell. Traveling on ten-foot wooden skis and pushing themselves through the snow, each with a single, long pole, they followed tracks of the suspected poacher that led them to Astringent Creek in the Pelican Valley on the north side of Yellowstone Lake.

There, in their favored wintering grounds, was the last free-ranging bison herd in the United States. Their numbers had dwindled to no more than a few hundred at the time. It is hard to imagine that some 100 years earlier, an estimated 30 to 60 million of these great, shaggy beasts roamed the vast grasslands that spread from the Mississippi Valley to the Rocky Mountains and from western Canada through Texas and into northern Mexico.

Hearing shots ring out, Burgess and Troike quickened their pace and soon saw Howell in the distance kneeling over a bison he had just killed. More bison lay dead nearby. Poachers could often get more than $300 – some $10,000 in today’s dollars – for a hide along with its head and horns from taxidermists and their clients. A small fortune lay at Howell’s feet, and there was no question that he would put up a deadly fight to keep his ill-gotten gains.

The good news was that Howell had his back to them and was busy skinning his bison. The bad news was that there were some 400 yards of open ground between them and Howell.

Burgess crept forward on his own, a .38 caliber revolver in hand. He was able to close in on Howell and get between him and the poacher’s Winchester repeating rifle that had been propped up on a bison’s carcass. Catching Howell completely by surprise, Burgess ordered him to drop his knife and raise his hands. Burgess and Troike took Howell into custody without further incident.

While Yellowstone Park was established in 1872, it was, in large measure, a park in name only. From the start, portions of the park had been threatened by railroad and mining interests. Its wildlife, especially its iconic bison herd, was left unprotected and, year over year, was being decimated by poachers. The capture and arrest of Edward Howell, however, marked a turning point that, in many ways, helped kickstart a new movement, a concerted effort to save America’s big game animals.

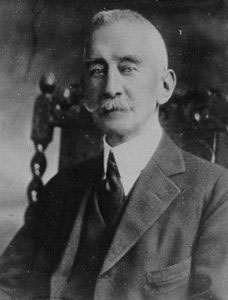

In times of peril, when things look impossibly bleak, in rides a knight in shining armor to save the day. It is, of course, the plot line of many a potboiler novel, but from time to time, it also happens in real life. Our hero in this case was a mild-mannered gentleman whose “armor” was his indefatigable spirit and his “lance” a pen that he wielded with an exceptionally deft hand.

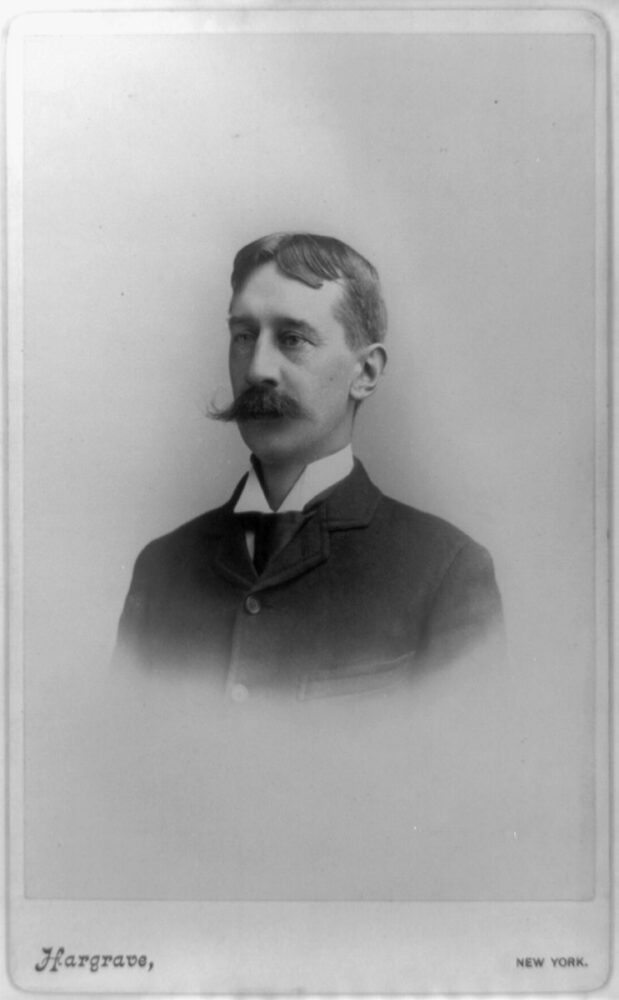

George Bird Grinnell was born in 1849 to a well-to-do New York City family and, when he was eight-years-old, his family moved to a house in upper Manhattan adjacent to the estate of the late John James Audubon, a 16-acre tract still largely made up of woods and fields. For a youngster interested in nature and wildlife, it was like a great wilderness in which he could explore, observe and learn.

George Bird Grinnell was born in 1849 to a well-to-do New York City family and, when he was eight-years-old, his family moved to a house in upper Manhattan adjacent to the estate of the late John James Audubon, a 16-acre tract still largely made up of woods and fields. For a youngster interested in nature and wildlife, it was like a great wilderness in which he could explore, observe and learn.

One of his early tutors was Audubon’s widow, Lucy, who continued to live on the property. Under her tutelage, George developed a keen interest in ornithology, especially the study of songbirds. At age twelve, he was gifted a shotgun with which he began to gather bird specimens on his own in the then still wild haunts surrounding his family’s New York City home.

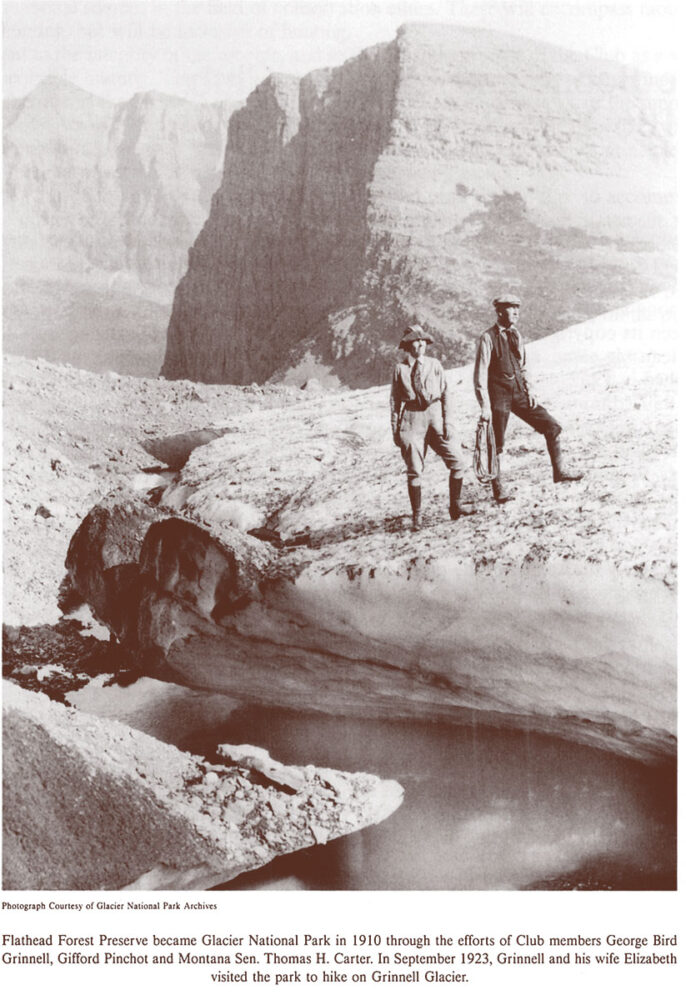

Grinnell’s naturalist interests took a hiatus when he entered Yale in 1866. In the summer after his graduation, he was one of a small band of Yale students asked to accompany famed paleontologist and Yale professor, Dr. Othneil Marsh, under whose tutelage Grinnell would earn his doctorate in 1880 on a summer expedition to Nebraska, Colorado and Wyoming to search for and excavate prehistoric fossils. This first trip sparked in Grinnell a lifelong interest in the American West and, by 1875, he had made six western expeditions helping him build, even at the young age of 26, a voice of authority on America’s fast changing frontier, especially its wildlife and increasingly threatened landscapes.

In the summer of 1874, General George Armstrong Custer asked Grinnell to serve as his naturalist on an exploratory trip to survey the Black Hills of the Dakota Territory and the following year he accompanied Captain William Ludlow, who had been on the Custer expedition, to the recently designated Yellowstone Park. It was Grinnell’s good fortune, however, not to join Custer on his next western trip thus missing the Battle of the Little Bighorn in June of 1876.

When not traveling, Grinnell worked at his family’s brokerage business but admitted that he really had no taste for finance. He thus jumped at an offer in the fall of 1876 to become the natural history editor for Forest and Stream, a weekly journal with a national audience that covered a wide range of outdoor pursuits and whose founder, Charles Hallock, was among the nation’s earliest advocates of the ideals embodied in the notion of sportsmanship and fair chase.

When not traveling, Grinnell worked at his family’s brokerage business but admitted that he really had no taste for finance. He thus jumped at an offer in the fall of 1876 to become the natural history editor for Forest and Stream, a weekly journal with a national audience that covered a wide range of outdoor pursuits and whose founder, Charles Hallock, was among the nation’s earliest advocates of the ideals embodied in the notion of sportsmanship and fair chase.

In 1880, Grinnell purchased Forest and Stream from Hallock and continued to own and edit this seminal publication for the next 36 years. It is difficult to over exaggerate the value of Grinnell’s voice through this publication in building public awareness and support for wildlife conservation and also fearlessly speaking out against market hunting, poaching and unsportsmanlike behavior in the field.

Bison were, by no means, the only American wildlife that faced a bleak and uncertain future around the turn of the 20th century. Wildlife scientists George B. Ward and Richard McCabe of the Wildlife Management Institute (WMI) noted that by the early 1900s, “Beaver, deer, elk, pronghorn antelope, wolves, bear, passenger pigeons, wild turkey, bighorn sheep, plumed birds and other wildlife were killed to extinction or nearly so for subsistence, market or as imagined obstacles to progress.”

A key first step in Grinnell’s crusade for wildlife was his effort to ban the killing of song and plumed birds whose feathers were used to adorn women’s hats. Plumed birds such as the snowy egret had already become scare by the 1880s.

“Very slowly,” he wrote in Forest and Stream, “the public are awakening to see that the fashion of wearing the feathers and skins of birds is abominable.” He took his effort one step further by creating in 1886 a new association “for the protection of wild birds and their eggs” as an adjunct group of the American Ornithologists’ Union.

He named the new association the Audubon Society, and by 1889 public membership in the society had grown to nearly 50,000. This success put a burden on the small staff at Forest and Stream forcing Grinnell to close shop on this fledgling organization. In 1905, however, the original concept was reborn by others as the National Association of Audubon Societies which continues today as the National Audubon Society, one of the best known conservation and education groups in America.

In 1885, Grinnell wrote a review in Forest and Stream about a book, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman, recently penned by a young but rising New York state political figure, Theodore Roosevelt. While generally favorable, Roosevelt was pricked by some of the criticism in the review and set out to meet Grinnell face to face. Fortunately, this encounter quickly turned cordial and prompted a long and very productive friendship between the two.

In 1885, Grinnell wrote a review in Forest and Stream about a book, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman, recently penned by a young but rising New York state political figure, Theodore Roosevelt. While generally favorable, Roosevelt was pricked by some of the criticism in the review and set out to meet Grinnell face to face. Fortunately, this encounter quickly turned cordial and prompted a long and very productive friendship between the two.

As wildlife historians Ward and McCabe point out, “With the younger Roosevelt, Grinnell shared his understanding and perspectives on the serious and fragile stature of American wildlife. In Roosevelt, Grinnell found an aggressive and politically mobile ally for his conservation crusade.” Both men, however, were not content to just talk about the perilous state of big game species in America. They were determined to move forward, to seek the enactment and implementation of policies and regulations that would serve to protect these species and, in so doing, preserve America’s hunting heritage.

As a first step, Roosevelt, conferring with Grinnell, invited a small but highly influential group of men to dinner in New York City in December of 1887. All the guests were avid big game hunters. From that event would form what is today the oldest wildlife conservation organization in America, the Boone and Crockett Club, or B&C as it is known to hunters and conservationists around the country.

The club’s first initiative was to seek effective protection for Yellowstone Park’s wildlife. Only a few months after the club’s founding, Grinnell wrote in a Forest and Stream editorial, “Every sportsman desires to have the great game which inhabits this park saved from extinction which is so surely impending for each species, unless rigid protection is afforded here.”

In a lucky coincidence, a Forest and Stream correspondent, Emerson Hough, and his photographer, Frank Haynes, who had together traveled to Yellowstone to promote the park’s winter wonders, arrived just after Edward Howell had been arrested by Burgess and Troike.

As Grinnell biographer John Taliaferro points out, “Hough’s colorful on-scene retelling of the capture of Howell, and Hayne’s photos of the carnage, had a sensational effect. Other papers picked up the story, and each episode of Hough’s serial in Forest and Stream was introduced by an editorial written by Grinnell denouncing Howell’s wholesale butchery and Congress’s shameful delinquency and encouraging readers to demand that the government protect the property ‘which belongs to those it represents.’”

Acting unusually swiftly, Congress did in 1894 pass the Yellowstone Park Protection Act that, among various conservation measures, prohibited the killing of wildlife in the park while also placing a representative of the U.S. Circuit Court in the park itself and appointing U.S. marshals to arrest game violators.

Grinnell’s efforts through Forest and Stream untapped, for the first time, widespread public sympathy for the plight of America’s wildlife and underscored the power of public outcry in influencing political action. As a member of the Boone and Crockett Club, Grinnell was also able to, through the club’s many influential members, gain key support in Congress for a legislative remedy for the Yellowstone’s needs.

Wildlife historians point out that the Yellowstone Park Protection Act brought the federal government into the wildlife conservation arena for the first time. The fight to save the park created a long-lasting “model of success” setting the precedent that the protection of wildlife and wilderness areas was an appropriate issue for national policy and law.

With the Boone and Crockett Club and Forest and Stream, Grinnell now had a powerful two-edged sword that he deftly swung in the years ahead. Less than a year after he was elected, President William McKinley was assassinated and Grinnell’s good friend and fellow B&C member, Theodore Roosevelt, assumed the nation’s highest office. Wildlife conservation and habitat preservation were among Roosevelt’s key priorities and, largely influenced by Grinnell, Roosevelt fostered a national policy that emphasized the “wise use of natural resources,” seeking their efficient and renewable administration in perpetuity. It was the critical first step in the road to recovery for America’s wildlife.

While his effort to save the buffalo of Yellowstone might well be considered Grinnell’s capstone achievement, he continued to vigorously champion wildlife species both large and small. At the turn of the century, waterfowl and upland birds continued to be hunted for sale in markets and in restaurants.

In the early 1890’s Grinnell jabbed his editorial finger at one of New York City’s poshest eateries, Delmonico’s, for serving increasingly scare woodcock. “For four centuries, “Grinnell wrote, “from the time of Christopher Columbus to Charles Delmonico, we have been killing and marketing game, destroying it as rapidly as we know how, and making no provision toward replacing its supply.”

It was part and parcel of his long running campaign to end hunting for profit. “The game supply which makes possible,” Grinnell emphasized in another Forest and Stream editorial, “the general indulgence in field sports is of incalculable advantage to individuals and the nation; but a game supply which makes possible the traffic in game as a luxury has no such importance. Public policy demands the traffic in game be abolished.”

In 1897, Grinnell worked closely with his friend and fellow B&C member, Congressman John F. Lacey, of Iowa, in championing a bill in Congress to form a federal law to ban the sale of wildlife products. The bill failed that year, but Lacey re-introduced the legislation in 1900 and, with strong support from Forest and Stream, together with the B&C and the Audubon Society, the billed passed.

The Lacey Act specifically prohibited the interstate shipment of illegally killed wildlife. Wildlife biologists and managers consider the Lacey Act of 1900 to be the legal cornerstone of wildlife regulations in the United States. Once again, Grinnell had fostered public sentiment and marshalled political support for legislation that would prove pivotal in our nation’s early conservation efforts.

The last two decades of the 19th century and the first two of the 20th were dark days for our nation’s wildlife. Some species, such as the buffalo, wavered on the edge of extinction. Others, such as the passenger pigeon, whose flights, noted John James Audubon in 1813, were so vast that, “they eclipsed the sun,” were gone by 1914. During that timeframe most all of our nation’s game species were, year over year, being reduced to remnant populations in isolated habitats. For many of those years, few if any efforts were being made to reverse this widespread and seemingly, inexorable downward trend.

The last two decades of the 19th century and the first two of the 20th were dark days for our nation’s wildlife. Some species, such as the buffalo, wavered on the edge of extinction. Others, such as the passenger pigeon, whose flights, noted John James Audubon in 1813, were so vast that, “they eclipsed the sun,” were gone by 1914. During that timeframe most all of our nation’s game species were, year over year, being reduced to remnant populations in isolated habitats. For many of those years, few if any efforts were being made to reverse this widespread and seemingly, inexorable downward trend.

It was precisely in that era that Grinnell rode in to the rescue. Like a true champion, he always made the “big play” when it counted, and went on to not only a great but, exceptionally long career. Forest and Stream was his editorial pulpit for more than three decades and he had been a member of the Boone and Crockett Club for 60 years when he died in 1938. He was a prolific writer and beyond the conservation arena also wrote extensively on Native American tribes and became a strong advocate for Native American rights in Washington, D.C.

He was the first to elicit public empathy for the plight of wildlife and to effectively harness such opinion to urge passage of conservation legislation. His crusades extended to all manner of wildlife and, along with his efforts to halt the indiscriminate killing of game, he played an outsized role in characterizing a new breed of hunter, the sportsman-conservationist.

The next time you’re in the field, whether high country elk camp or duck hunting lodge, may I suggest you raise a glass to George Bird Grinnell. Perhaps more than anyone else, he defined, at least in one important sense, the best of who you are.

The Harding is a traditional barrel handle hunting knife. The beautiful, warm handle is made from curly birch and darkened oak separated by layers of leather. It has a full length tang. The blade is made of razor sharp triple laminated stainless steel. It comes with an embossed leather sheath with a handle butt retainer. A knife you will treasure. Buy Now

The Harding is a traditional barrel handle hunting knife. The beautiful, warm handle is made from curly birch and darkened oak separated by layers of leather. It has a full length tang. The blade is made of razor sharp triple laminated stainless steel. It comes with an embossed leather sheath with a handle butt retainer. A knife you will treasure. Buy Now