I parked the truck and killed the lights, keeping the engine running for a few minutes to soak up as much warmth from the heater as I could before braving the morning chill. The last sip of black coffee was cold, so I turned off the ignition and grabbed my old Remington 12 gauge. After adjusting my waders I clomped towards the duck impoundments, with the dim glow of the coming sunrise on the eastern horizon providing enough light to see my way.

We hunters had gathered in the little open shed at South Carolina’s Bear Island Waterfowl Management Area, south of Charleston, hours it seemed before official daylight, sipping steaming black coffee to fight the January morning chill while waiting for Bear Island Manager Johnny Hiers to check us in and direct us to our assigned hunt areas. By the mid-1970s East Coast waterfowl populations had rebounded from the steep decline of the 1960s, almost back to the heyday hunting levels of the 1950s—and there was no better public hunting to be found than at Bear Island. On that frigid morning some 40 years ago, I had drawn an area with two impoundments separated by a dike.

But first Hiers had to explain the rules of the hunt. Some were completely serious: the limit was five ducks, but there were also limits on certain species and sexes. Some, however, were not so serious— except perhaps for novice hunters.

“You can shoot mallard drakes and you can also take a mallard hen, but make sure it’s a mallard hen and not a black duck hen. It is illegal to shoot a black duck hen. They look very similar, but you can tell the black duck hen from the mallard hen because of this distinctive red line around the eye,” Johnny would say, while pointing to a thin, barely visible red membrane around the eye of a mounted black duck hen. That drew a hearty laugh from all the hunters once they realized Hiers was pulling their legs.

I walked down the dike, stopping about midway to check the two impoundments in the glow of first light. The pond to the right was mostly open, something I should have made a mental note of. Tall stands of cord grass filled the one to the left. I eased down the dike to the edge of the grassy pond and waited. The morning air was filled with bird chatter—quacking, whistling, flocks hailing each other—and the whirr of wings as flights of ducks, barely discernible in the dimness, cruised past in search of a place to land.

A distant shot to the east heralded the arrival of official shooting hours. By now I could see ducks flying everywhere, mostly far across the grassy impoundment, but none were coming towards my hiding spot in the high grass. Hearing the whirring of wings on the pond behind me, I climbed up the dike and took a spot in some grass on the side of the dike, just as a pair of blue-winged teal shot by. I swung and dropped the drake about 30 yards from the edge of the dike.

I took one step towards the duck to retrieve it, but felt no bottom under my wader boot. There was a reason the grass was sparse in this pond—it was too deep!

Fortunately, I caught myself and avoided floating my hat and filling my waders. Retreating to the grassy pond across the dike, I found my spot in the high grass just in time for a flock of ringnecks to swing across the pond from my right. Suddenly, they swerved and came back in front of me, flying from left to right. I raised the 12 gauge and walked through the flock, firing three shots—and three ringnecks in succession dropped into the water.

It was barely daylight and I had already recorded the best waterfowl shooting of my life, four ducks with four shots!

One more, I thought, and I’ll have a personal best.

By now the sun was shining bright in a bluebird sky. It had turned into a summertime day in January, and the ducks were quickly finding places to land and feed. The calling clatter of just a few minutes earlier was beginning to grow soft, replaced by the muted sounds of feeding chatter and accentuated by incessant highballs from callers across the way, trying to lure high-flying flocks to drop down.

I could still see a few birds winging over the far side of the impoundment, so I waded towards the middle, hoping to pick up a stray and fill my limit. As I settled into a big clump of cord grass, I could see a duck flying straight at me about 200 yards out. I readied the 12 gauge and waited. When the duck closed to under 40 yards I raised and shot—and missed!

There went the chance to increase my personal-best record on the duck pond. The bird kept coming and I fired again – and missed again! Then, at 20 yards, I fired and dropped my limit filler. Although I had missed on a five-for-five shot, it was still a very good day on the duck marsh.

I waded to the where the duck had fallen into the high cord grass, but there was no duck there, despite several feathers floating in the air. So, I began walking a search grid—back and forth, east and west, then north and south, covering an area about 20 yards square—but found no duck. By now the sun was high and I was sweating under all my layers of clothes, so I headed to the truck, picking up my three ringnecks on the way.

Back at the check-in shed, I asked Donald Beach, assistant WMA manager, to help retrieve my other two ducks. Donald’s black Lab quickly brought my blue-winged drake, then we waded into the grassy pond to try to find my fifth bird. By now it was so hot I had shed my hunting coat and rolled up my shirt sleeves. We found the clump of broken grass I had left for a marker and began looking for my duck.

After a short search, Donald called, “I found your bird.”

I waded over to the area I had thoroughly searched less than an hour earlier. There, a big clump of cord grass had been wallowed down with muddy water all around it. A duck wing floated on the water on one side, and another wing lay on the other side.

“What happened to my duck?” I asked, incredulously.

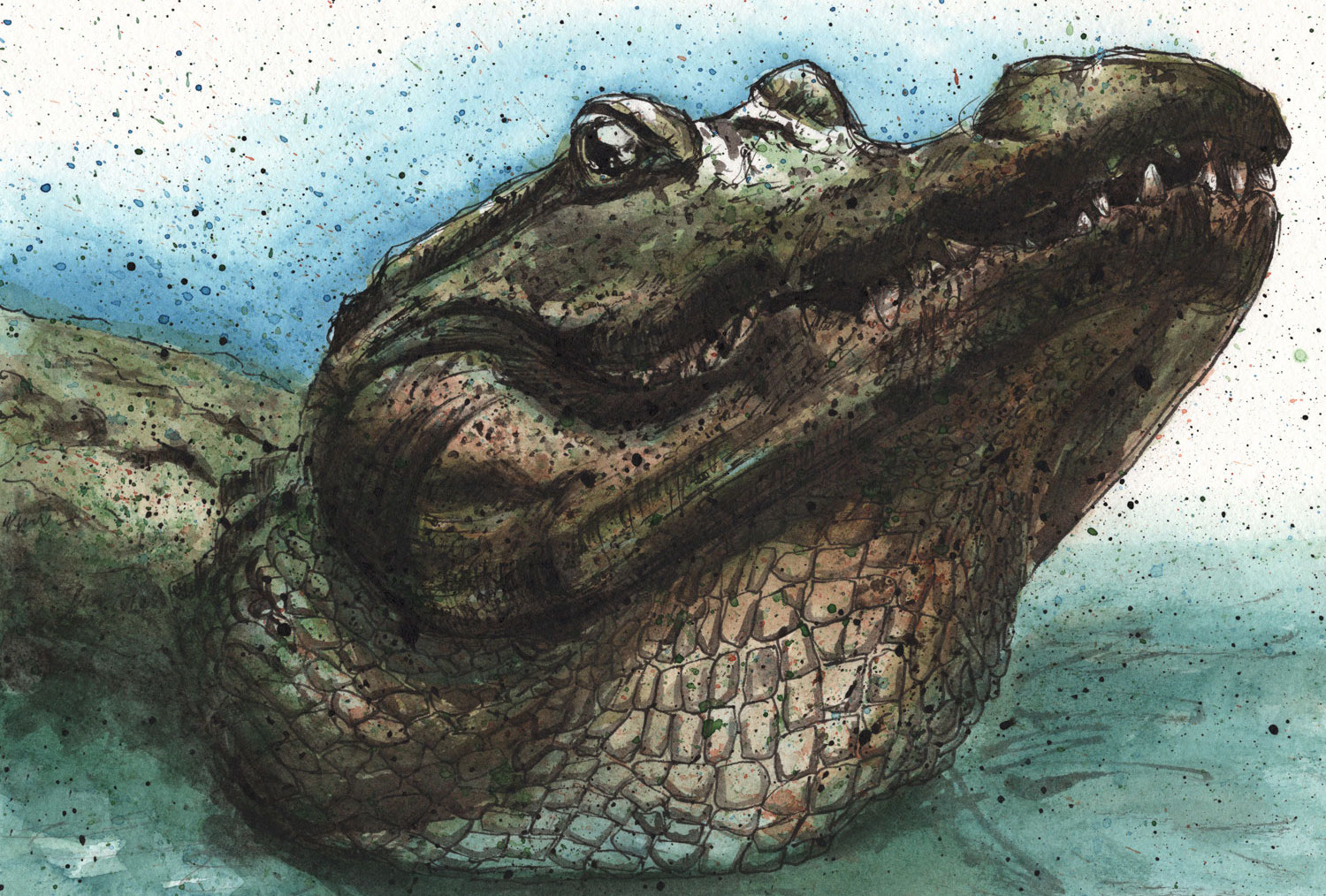

“A big gator,” Donald said, holding both arms out and demonstrating a gator chop. “When he ate the duck, the wings fell off either side of his mouth.”

During very cold weather alligators may become dormant, but on sunny days they will come out to warm up in the sun and feed. My duck apparently dropped right in front of this big gator, and he had an easy breakfast while I stomped all around him. Despite the unseasonably warm weather that morning, a shiver ran up my spine.

“I have one more question,” I said.

“What’s that?” Donald asked.

“What the heck are we doing standing here? Let’s get out of here. Now!”

An extraordinary collection of fifteen stories that celebrate America’s unquenchable thirst for excitement.

An extraordinary collection of fifteen stories that celebrate America’s unquenchable thirst for excitement.

Great American Adventure Stories contains page-turning accounts of the Galveston Hurricane, the Alaska Gold Rush, a robbery featuring Jesse James, an eyewitness account of the Johnstown flood, and much more. For a taste of the American frontier, Daniel Boone and famed scout Kit Carson depict what they saw and experienced as the country expanded and blossomed in the West. These accounts all have one thing in common: They capture the grit and spirit of people who made America what it is today.

Created for adventure addicts there has never been a more exciting collection of stories that celebrate the indomitable spirit of the American character. Buy Now