Perhaps it’s simply luck. Perhaps it’s some sort of obscure instinct which guides a hunter. Or possibly it is as the Indians believe—if you live right and observe the proper rituals, the spirits of the woods and prairies will take you by the hand and lead you to good hunting. I know that, for my part, some of the best hunting I have ever encountered has come to me through no conscious process on my part. It has been as if I were guided by some unknown hand.

The quail of the little milpas, which is what the Mexicans call their farm fields, are a case in point. I discovered them by accident. I discovered them because I needed them, because I had to have them if I were to get in much bird shooting. It was as if some beneficent spirit had conjured them up for me out of my need.

Now the Gambel’s quail of the Southwest is almost entirely a desert bird and not, like the Eastern bobwhite, a dweller on farms and fields. The Gambel’s does not get on well in the modern world, and for the most part he has disappeared from the big irrigated valleys of the Southwest. Clean farming, the habit of burning off the grass each winter, and predatory domestic cats, which all Americans seem to love (as well as the ever-present and just as predatory small boy with his BB gun and his .22), all serve quickly to exterminate him around most farms. The birds have survived in hordes in the deserts, but civilization nearly always spells their doom.

So I had no right to find those coveys where I did. They were simply born of my need.

There is excellent bird hunting around Tucson, Arizona, but most of it is from 20 to 40 miles away and out of reach of the man who holds a job and must confine his longer jaunts to weekends. I wanted a spot where I could shoot a few birds after my day’s chores were over—and I found it—easily, quickly, almost as if I had known about it all the time and had just remembered.

It was a few years ago, and I had just moved to Tucson from the high, cold Coconino Plateau in northern Arizona, where no quail live and where wild turkeys are the only native non-migratory game bird. Turkeys, of course, afforded considerable excitement and exercise, but not much shooting, since in those days the bag limit was two. So I was desperately anxious to polish up my quail technique.

Gloomily, I went to my job the morning of opening day while more fortunate human beings headed for the desert and the merry Gambel’s quail. At 3:30 p.m., when I could slip away, I gathered up the wife and a couple of guns and went out aimlessly, wistful but planless.

We passed the suburban homes of wealthy Easterners and of not so wealthy natives, tourist hotels, beer joints, and filling stations. Surely there were no quail around here.

About three miles from home I saw a little-used road turning off into a patch of cholla and greasewood toward Rillito Creek. Still aimless, I took it.

“Where are we going?” my wife asked politely.

“I don’t know,” I told her.

After a quarter of a mile a barbed-wire fence stopped us. I got out to open a gate, and there, fresh and sharp in the soft dust, were quail tracks—unmistakably quail tracks, the sign of a good-sized covey.

So we took our guns and moved cautiously into the mesquite thicket on the other side of the fence. More tracks crisscrossing the soft earth, feathers, dust baths. In the distance I heard the sweet, fluty call of a cock Gambel’s quail.

So we mooched along, straining our ears, guns ready. Presently we came to a little irrigation ditch bordered by a high, thick pomegranate hedge full of red and orange fruit.

Then, B-b-b-b-b-, the unmistakable sound of a flushing quail. There he was, a beautiful cock bird, towering up out of the pomegranates. I shot and watched him collapse. It was then I heard a yell with distinctly Mexican overtones.

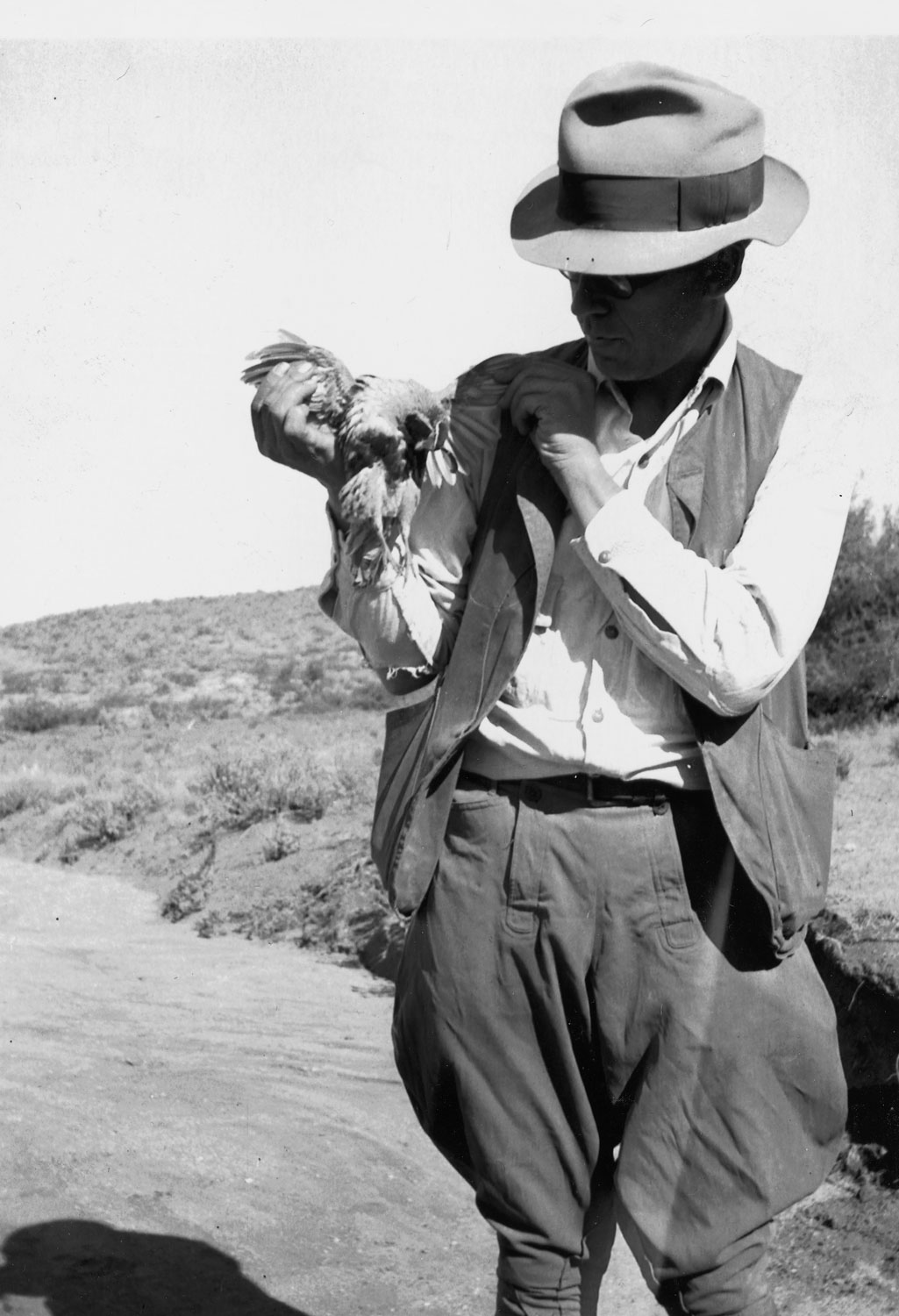

Astonished, I pushed through the hedge and saw something the presence of which I hadn’t expected—an adobe house. And standing in front of it, beside a washtub, was the angriest Mexican woman I have ever seen. She gripped a soapy quail in one hand and waved it furiously as she sputtered at me.

The Mexican people, I am convinced, are the fastest-talking people on this globe, and when angry, they talk at least nine times as fast as when they are calm.

She told me what she thought of gringos in general, of hunters as a race, and of me in particular. She also remarked about the morals of people who went about shooting quail so that they fell into washtubs and frightened good Christian women half out of their wits. She even brought my grandmother, my great-grandmother, and my great-great-grandmother into the discussion.

My wife, fortunately, didn’t understand much Spanish, or perhaps I should never have regained face with her. We both just stood there and took it.

Then a tall, solemn Mexican appeared, hoe in hand. He listened impassively, now and then stroking his handlebar mustache. But after a few minutes of it he caught my eye and slowly winked. I grinned, and he grinned.

La Madama turned then, saw her spouse, and landed on him. Would he stand there like a big rat, she demanded, and simper when a gringo had just shot her with an escopeta (gun)? Ah, if she had only married a man instead of a spineless hundido that could be trodden upon like a worm! Out of breath, she paused then as he shrugged. She was resigned to her fate, helpless with indignation.

It was my turn now. I assured her, in my best Spanish, that if I had known so lovely and gracious a lady was working on the other side of that beautiful hedge, I should never have shot, that I was the most humble and remorseful of men, with a head that must remain forever bowed in contriteness and shame.

She favored me with a smile then, the first rift in the clouds, and my wife completed the peace treaty by making friends with a shy 4-year-old girl who came peeking out of the adobe hut.

So we met Juan and Mercedes, and we also met the quail—the “muchos codornices” which Juan told me about. “Don’t shoot the cow or the children,” he said to me, “and you are welcome.”

A little exploring gave us the explanation of why the quail were there. Although we were hunting only a few miles from the center of Arizona’s second largest city, we were for all practical purposes in Sonora, Mexico.

A dozen Mexican families lived along the creek there, farming little milpas of corn and beans and chile, raising scrubby chickens, tending gnarled little orchards, and now and then butchering one of the steers that fed in the mesquite pasture. They were poor, hard-working people and, like their relatives in Sonora, almost never hunted. If they did pot something now and then with a rusty old single-barreled shotgun, it was a cottontail or jackrabbit, never a quail or a dove, since they didn’t have the skill to hit the birds on the wing and felt it a waste of money to shoot them.

Mexicans of their class stew up everything with chile, garlic, and onions anyway, so they think jackrabbit meat is just as good as quail, and one shell gets far more of it. The only time I felt Juan’s downright disapproval was one day when he showed me a closely huddled covey that I could have practically exterminated with one shot. I refused to shoot, and he showed plainly that he thought I should have my head examined.

Those milpas were really lovely, a fit setting for hunting the smartest, gamest bird in the Southwest. The big, feathery cottonwoods along the ditches were just turning then, flaunting great masses of clear, bright yellow against the transparent blue of the southern Arizona sky. Scarlet strings of chile hung against the light-brown adobe houses, and the fields were checkerboards of green and gold.

When we left the adobe of Juan and Mercedes that first day, we hadn’t gone more than 50 yards when we flushed a covey out of an ancient cottonwood overgrown with grapevines. I had heard about such things before—or, rather I had read about them in stories of hunting bobwhites and ruffed grouse—but never before had I seen Gambel’s quail eating grapes. But I was warned, and when, 50 yards or so farther on, another covey burst out of a brush pile, we both went into action and got three.

Writers are fond of generalizing about the habits of game, and I have done some plain and fancy generalizing myself. I honestly thought I knew about as much about the habits of Gambel’s pretty quail as anyone. Yet that day I had to discard practically everything I had learned from tramping over the deserts for nearly 30 years. Those birds were Gambel’s quail in form, in color, in calls; but in action, they were like bobwhites. Hunting them was bobwhite hunting in a Mexican environment.

One field had been planted to wheat, and it must have contained six or seven coveys of from ten to 20 birds each. Juan had harvested it with a hand scythe, and the stubble was a good six inches high—high enough to conceal the feeding birds and also to make them fairly hard to find when we grassed them, unless we kept our eyes open. Those birds did not run when they heard us coming, as Gambel’s so often do. Instead, they hid and burst out from beneath our feet when we were almost ready to step on them. Sometimes they flew over into an adjoining field, but usually they fanned out, scattered, and hid again in the same wheat stubble.

Ordinarily, the quail of the deserts flush at from 20 to 30 yards; sometimes, when they are wild and the ground is quite bare, from 35 to 40. These birds exploded at our shoe tops. Bobwhite hunting? Nothing else! And for the first time in my career, I longed passionately for two things almost no Southwestern hunter ever buys—a really good bird dog and an open-bored gun.

Used to longer flushes, I ruined the first three birds I took out of the stubble patch. I shot too fast, and, even with the modified barrel, I reduced them to masses of pulpy feathers. After that I waited them out and took them at ordinary range—or what is ordinary range in the Southwest. A good bird dog would have been in his element then, as the birds lay well.

I followed one covey into a thick patch of mesquite, and there I got what I imagine grouse shooting is like. They had scattered and at least half of them lit in trees. I’d hear the whir of wings and see them driving through the foliage.

I won’t tell my score. I’m no grouse shooter; I’d like to be, but I have never had the opportunity. So those who have hunted grouse know about what an open-country shot armed with a close-bored 20 gauge with 30-inch barrels would be likely to do under such circumstances.

I could hear the little woman’s gun popping in the stubble still, and when I joined her I found her picking up the bird which completed her limit. I still lacked two, but we had enough. So we headed back toward Juan’s by the way of a brushy draw to pick up some cottontails for our host.

We rolled three and missed as many more by shooting over them with our straight-stocked guns. I completed my bag of quail with a pair of shots I still remember voluptuously, although the misses I had made in that pesky mesquite thicket seem somehow to have escaped me.

We were strolling along, expecting nothing, when two birds exploded from the top an of old peach tree on the edge of a field. I made as neat a double on them as I have ever made, shooting the moment they were silhouetted against the sky. I found them both on the far side of the tree, so dead they hadn’t moved—and that, for a Gambel’s quail, is very, very dead indeed.

As if we hadn’t already had enough sport, we ran into a fine flight of doves. We had seen a good many that day, scattered and feeding in the stubble, but we had ignored them for the quail.

Now we took our stands beside some high cottonwoods and shot while the doves came streaking over, headed for their roosts in the bottom of Rillito Creek a quarter of a mile away. We found ourselves shooting cleanly, swinging smoothly, and in a few minutes we had ten doves.

The sun was about to set, so we knocked off, delivered our thanks and our rabbits to Juan and Mercedes, and headed for the car.

Would our kind hosts have either doves or quail? No, not they! But on the other hand, they were very fond of weenies. We said we’d bring them some next time. And we did.

Two or three afternoons a week for the rest of the season we shot on Juan’s place, delivering our tribute of hotdogs and returning with bags of sporty birds, large, fat, and delicately flavored from eating all sorts of food ordinarily unknown to desert-dwelling Gambel’s—grapes, dried apricots, wheat, and milo—even maybe a spot of chile now and then.

Never did those little milpas fail us. Without intending to, Juan had arranged an ideal setup for birds. He had never heard of clean farming, so his ditches and field corners were high with brush and weeds. He didn’t prune his fruit, so his trees did just as well for roosts as the horny palo verdes of the desert. He raised crops to eat instead of to sell, and as a consequence the birds had plenty of food, whereas most Americans in the Southwest now raise either truck or cotton.

I wish this story could end on a happy note, but our first season there was our last. A wealthy Easterner with a yen to be a Southwestern country gentleman saw Juan’s place and was so charmed by its rustic simplicity that he bought Juan out, and Juan and Mercedes went back to Sonora.

It’s a model American farm now. The fence corners are clean, so are the ditches, and the fruit trees have been pruned and sprayed. The fences now bear “No Hunting, No Trespassing” signs, but there is no need for them. The quail are no longer there.