I could go on and on; the bill of laden is interminable . . . all the things that can displace or render to anguish a joyful day of hunting or fishing. But it’s quibbling over pocket money.

Folks who’ve lived past yesterday will tell you life is unpredictable. But I don’t know. Seems to me, there are phenomena that impinge the blissful and disordered drift of my existence with incontestable and disturbing regularity. After these many decades of living, I have determined it is impossible to forecast with certainty the precise construction these interruptions will assume, it is beyond the contest of Fate that they will happen.

Folks who’ve lived past yesterday will tell you life is unpredictable. But I don’t know. Seems to me, there are phenomena that impinge the blissful and disordered drift of my existence with incontestable and disturbing regularity. After these many decades of living, I have determined it is impossible to forecast with certainty the precise construction these interruptions will assume, it is beyond the contest of Fate that they will happen.

It started when I was a kid. Mama would sniff me out just before 7 o’clock every Saturday night, inconveniently ushering me off to the bathtub, five minutes before my uncle called to ask me coon hunting. As surely, the day Daddy picked for me to mow the grass was my one free afternoon after school . . . with the moon full and the redbreasts ripest on the bed. Or just before I was off to see Richard McComb’s new red bone pup, I was conscripted to the garden to pick snap beans.

Then and there I began to understand, that – in the sphere of my most passionate pursuits – my being might be a bit more foretellable than my Grand-Pap made it out to be.

At the time, of course, these interferences were merely zephyrs of caution against the greater gales of inevitability that would follow. Little did I know how brusquely the winds could blow.

Older and out on my own, however, I figured I would take hold of things. Except it didn’t get any better. First off, I messed around and fell in love, got married and assumed additional preclusive probabilities of lifetime consequence. Some of which I couldn’t at the moment dream of. But then, somehow, they seemed fewer, hadn’t rooted as fully and were more sufferable.

Older and out on my own, however, I figured I would take hold of things. Except it didn’t get any better. First off, I messed around and fell in love, got married and assumed additional preclusive probabilities of lifetime consequence. Some of which I couldn’t at the moment dream of. But then, somehow, they seemed fewer, hadn’t rooted as fully and were more sufferable.

Or so I believed.

When I got Bess, my first all-my-own setter pup, Loretta would go with us regularly to hunt and train, and we still had wild birds a couple of miles from the house. We were three – madly in love, relishing it together – autumn swelling, the sumac and sweetgums taking color, and you could hear the Bobs calling the coveys to order each morning at the blue of dawn. In incomparable splendor, October passed its still flaming torch to November, the mornings broke over misty, crisp and cool, and the woods and meadows waxed burnt fawn, burgundy red and tobacco gold. Just before quail season, the frost nipped the cover back, and I got my first Parker gun. The pup was beginning to hold her birds, and I gave my bride a new pair of Irish Setter hunting boots.

Life was about as beautiful as it gets, only, as I was about to find again, every bit as conventional, and I went to the mailbox that same mellow, mid-November afternoon — only to open “Greetings” from Uncle Sam.

Along about then, I decided whatever might be waiting to happen . . . would . . . and there wasn’t much I could do about it.

I have since within the sporting life suffered many such vagaries of certainty . . . to the point that there is no longer uncertainty. As the miles and seasons have turned by, I have been led to anticipate that such covert probabilities lurk endlessly. That you cannot plan them aside, and that barring evolution into an utterly celibate, cantankerous and reclusive curmudgeon of despicable civil estimation . . . however tempting when the big browns are nearing the reds . . . no one of us will ever – as I have strived all my years – avoid or control them.

I have since within the sporting life suffered many such vagaries of certainty . . . to the point that there is no longer uncertainty. As the miles and seasons have turned by, I have been led to anticipate that such covert probabilities lurk endlessly. That you cannot plan them aside, and that barring evolution into an utterly celibate, cantankerous and reclusive curmudgeon of despicable civil estimation . . . however tempting when the big browns are nearing the reds . . . no one of us will ever – as I have strived all my years – avoid or control them.

Even an attempt to confer upon younger sports the wisdom I have suffered regarding such inconveniences wanes futile, as I can offer no remedial salvation. As with any unpredictably predictable quarry they will choose to pursue within a social existence, it’s simply the inalterable nature of the beast.

I suppose the one best prescription is compromise, which is doing something you don’t want to, rather than incur the hell you pay if you do the something you’d rather. Which nobody has ever done gracefully, even Jesus midst the money-mongers. There’s also a modicum of satisfaction in cussin’ for a spell, so long as you do it under your breath.

It does loom troublesome, however, to leave the innocent unaware, as some of the impositions to be encountered may be disguised in surroundings so originally benign as to escape detection.

For instance, young man, if you’ve found you love big rivers and wild trout much as you love the girl you will marry, and she desires a traditional June wedding, I can promise that the day before your (pick a year) wedding anniversary when she’s asked to go to Hawaii, the best fly guide on the Big Hole will call and announce the grandest salmonfly hatch in the history of Montana. Just as I can give you better than Vegas odds that her birthday will fall within the second week of November, a lovely month, but also the perennial pinnacle of the whitetail rut. Further, that in a year when the Huns are thick as love grass, her best friend and sorority sister, with her husband and two kids, will call to visit – the only time they can come – and want to go to Disney World the first full week of October, which is your annual prairie bird trip.

For instance, young man, if you’ve found you love big rivers and wild trout much as you love the girl you will marry, and she desires a traditional June wedding, I can promise that the day before your (pick a year) wedding anniversary when she’s asked to go to Hawaii, the best fly guide on the Big Hole will call and announce the grandest salmonfly hatch in the history of Montana. Just as I can give you better than Vegas odds that her birthday will fall within the second week of November, a lovely month, but also the perennial pinnacle of the whitetail rut. Further, that in a year when the Huns are thick as love grass, her best friend and sorority sister, with her husband and two kids, will call to visit – the only time they can come – and want to go to Disney World the first full week of October, which is your annual prairie bird trip.

If this particular interpretation fails to meet the particulars of your individual situation, I can assure you that whatever its elements, the consequences will not be dissimilar.

It hardly ends there. Beyond the social intermissions, there are the painful contrivances of chance . . . the bittersweet angst of dilemma. To point, for the very week that you booked three years ago the pack-in, Wyoming elk trip you’ve yearned for since you were in knee britches – one it’ll take another three years to mend – an SCI friend will call, inviting you to begin a 21-day pre-paid safari to East Africa.

Or one morning at breakfast, just after you’ve promised your Missus you’d refurbish the kitchen and whisk her off to a second honeymoon on Christmas Island – and you’re limply back from her serendipitous rejoinder to the boudoir – you’ll find a fresh ad in the Connecticut Shotgun listings for the droplock Westley-Richards 28 gauge you’ve always pined for. Or right after you’ve mortgaged the farm for a five-year waterfowl lease in Arkansas green timber, an elder will pass without kin, and you’ll be offered an almost impossible membership at the old Swan Island Ducking Club.

Or one morning at breakfast, just after you’ve promised your Missus you’d refurbish the kitchen and whisk her off to a second honeymoon on Christmas Island – and you’re limply back from her serendipitous rejoinder to the boudoir – you’ll find a fresh ad in the Connecticut Shotgun listings for the droplock Westley-Richards 28 gauge you’ve always pined for. Or right after you’ve mortgaged the farm for a five-year waterfowl lease in Arkansas green timber, an elder will pass without kin, and you’ll be offered an almost impossible membership at the old Swan Island Ducking Club.

On it goes, down to the assurances of everyday living. Everybody knows that if you go today, it should have been yesterday, or if you go tomorrow, it would best have been today. That three days before you’re invited to join the East Addieville All-Star Clays Squad, you’ll fall into the most convoluted shooting slump of your life. That if you brag on your best dog . . . he’ll come down with the limber tail, or blow through the next bevy of birds like a bull through a bath curtain.

I could go on and on; the bill of lading is interminable . . . all the things that can displace or render to anguish a joyful day of hunting or fishing. But it’s quibbling over pocket money. It’s all going to happen anyway, with uncanny dependability, and I’ve posted fair warning.

Except that on this one, misery craves company, and when it comes to finding the middle ground . . . young or old . . . we’re all in the same boat, pulling against the current.

Except that on this one, misery craves company, and when it comes to finding the middle ground . . . young or old . . . we’re all in the same boat, pulling against the current.

Therefore, I’ll consider it kindly, when you can drop anchor for a minute, if you’ll send along your best secrets.

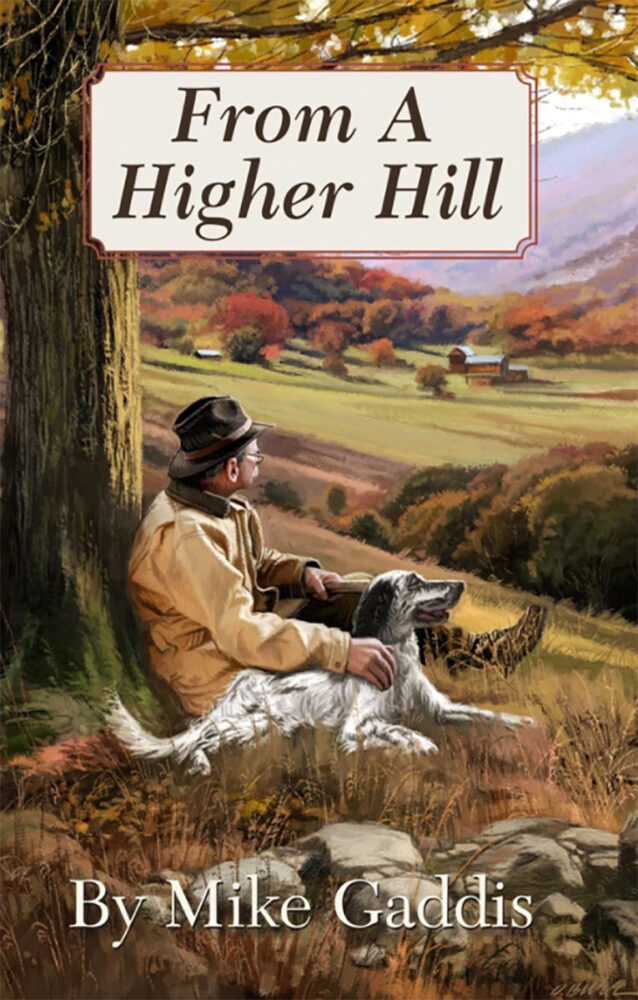

Life can be likened to ascending a mountain. The higher you climb, the more years you have beneath you, the farther you can see, the more unobstructed the view, the more you understand.

Life can be likened to ascending a mountain. The higher you climb, the more years you have beneath you, the farther you can see, the more unobstructed the view, the more you understand.

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come.

Upon this lofty precipice, one of the most celebrated and insightful sporting authors of our time again reaches beyond himself, this time retrieving sixty-five more episodic explorations of the sporting life, the whole of which transcend contemporary perspective, and ascend to rare and unexcelled poignancy. Buy Now