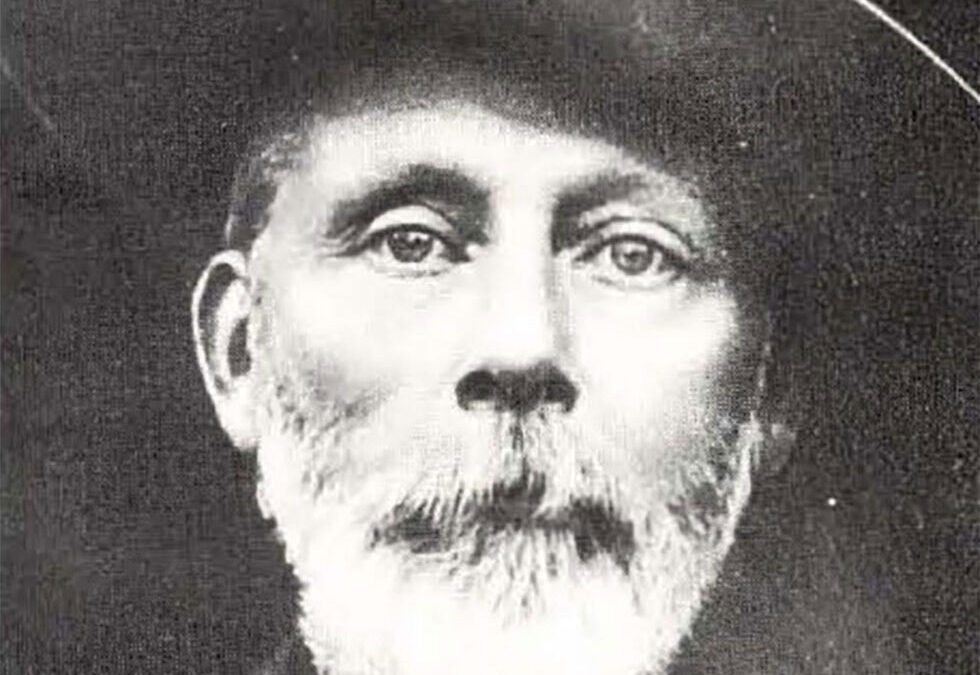

In the words of his contemporary and close friend, Teddy Roosevelt, Frederick Courteney Selous (1851-1917) was “the greatest of the world’s big-game hunters.”

Certainly, there were few sportsmen of the late Victorian and Edwardian period who would have disputed the American president’s evaluation. Thanks both to his prowess afield and the literary gifts he brought to the many books and countless articles in which he described his hunting exploits, Fred Selous (pronounced Se-ū), became a famous as well as immensely popular figure.

It is small wonder that Selous frequently has been credited with being the model for H. Rider Haggard’s famed fictional character, Allan Quatermain. In retrospect, however, it is Selous’ endless joie de vivre — he was one of those rare individuals who always lived life to its fullest and found constant joy in the process — which makes him such an appealing, attractive character.

Selous was born at the family home in Regent’s Park, London (the same area of the city that is now the location of one of the world’s most famous zoos) on the last day of 1851. From early childhood he exhibited a great love of nature and the outdoors, and on more than one occasion during his youth his preoccupation with sport got him into trouble. For example, during his days at Bruce Castle in Tottenham, where he began his formal education at the age of nine, he constantly incurred the wrath of the headmaster with his mischievous escapades and daydreams of hunting adventures in Africa. Indeed, this rather dour, humorless individual, who had no time for Selous’ boyish high spirits and pranks, informed the authorities at Rugby School that the granting of admission to Selous would be a grave mistake certain to lead to the most unfortunate consequences. Selous nonetheless gained entrance there from the beginning of 1866 through the spring term of 1868.

Selous was born at the family home in Regent’s Park, London (the same area of the city that is now the location of one of the world’s most famous zoos) on the last day of 1851. From early childhood he exhibited a great love of nature and the outdoors, and on more than one occasion during his youth his preoccupation with sport got him into trouble. For example, during his days at Bruce Castle in Tottenham, where he began his formal education at the age of nine, he constantly incurred the wrath of the headmaster with his mischievous escapades and daydreams of hunting adventures in Africa. Indeed, this rather dour, humorless individual, who had no time for Selous’ boyish high spirits and pranks, informed the authorities at Rugby School that the granting of admission to Selous would be a grave mistake certain to lead to the most unfortunate consequences. Selous nonetheless gained entrance there from the beginning of 1866 through the spring term of 1868.

Fortunately for all concerned his housemaster while at Rugby was the patient, kindly J.M. Wilson, who proved the perfect counterfoil for the irrepressible young Selous. As Wilson would later reminisce, he was warned that the boy was a veritable plague, and when he wrote to his doom-saying correspondent to inquire as to the nature of Selous’ misdemeanors, the reply came back: He breaks every rule; he lets himself down out of a dormitory window to go birds’ – nesting; he is constantly complained of by neighbors for trespassing; he fastened up an assistant master in a cowshed into which he had chased the young villain early one morning; somehow the youngster scrambled out, and fastened the door on the outside, so that the master missed morning school.

Far from being put off by these alleged crimes by a young hellion, Wilson replied that Selous was just the boy for him, and thus began the phase of his education that the renowned hunter would always remember with great fondness. While at Rugby he developed the athletic prowess and coordination that subsequently would stand him in good stead in the field. Among the sports Selous participated in on a varsity level were swimming, track, rugby, cricket and riflery, but characteristically, it is exploits of a rather different sort for which Selous is fondly remembered to this day.

He was constantly in and out of trouble for taking specimens with his “tweaker” (a small-bore gun he kept hidden at a farmhouse located conveniently close to Rugby), and at one point Selous had the audacity to rob eggs from an island heronry on Lord Craven’s property at Coombe Abbey. Selous was very nearly caught in the act, but his speed as a swimmer and runner enabled him to make good his escape.

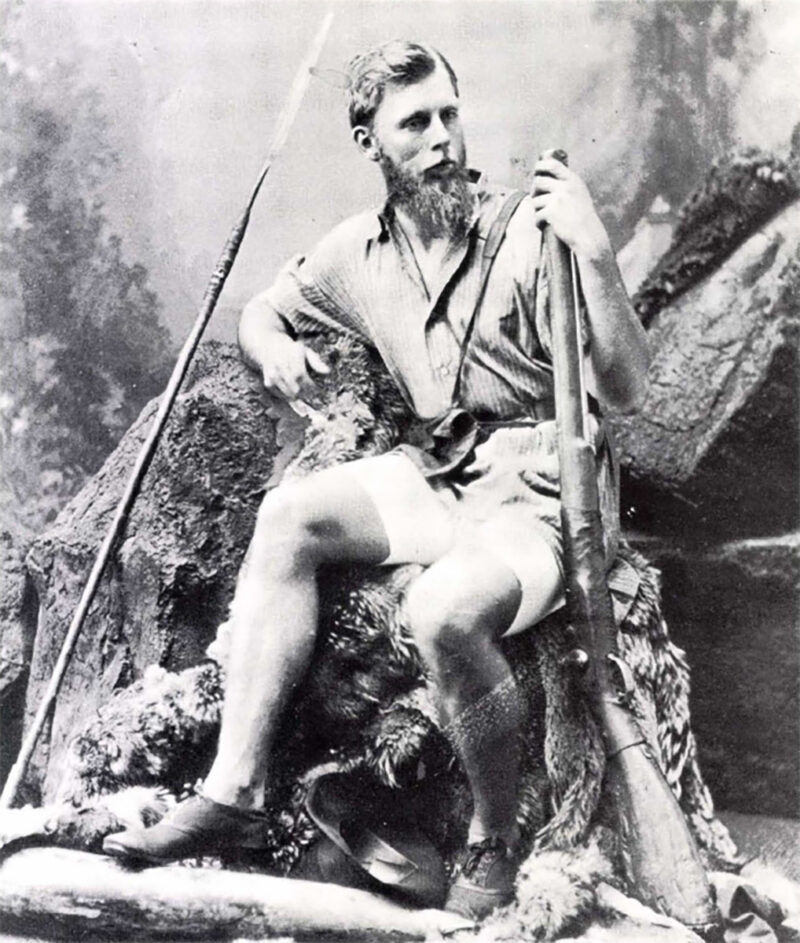

For all the disciplinary havoc he wrought at Rugby, there was a more serious side of Selous which developed simultaneously. He was a founding member of the School’s Natural History Society, and his enterprising ingenuity in obtaining specimens for its collection was unrivaled. Similarly, although generally an indifferent scholar, he excelled in geography and as a student natural historian. It was also at this point in his life that Selous developed a fascination with Africa and became increasingly obsessed, far beyond the ordinary scope of passing adolescent fancies, with the continent. When his father had first brought the blond-headed boy with piercing blue eyes to Rugby, he had immediately declared to his headmaster that he meant “to be like Livingstone.”

Selous read incessantly in the accounts of African missionaries, travelers, hunters and explorers, and he was especially attracted to Roualeyn Gordon-Cumming’s The Lon Hunter in South Africa and William Charles Baldwin’s African Hunting and Adventure. His determination to seek his fortune in Africa remained steadfast throughout his teens. After he left Rugby, periods of study at the Institution Roulet in Neuchatel, Switzerland and at University Medical College, London, interspersed with forays in Europe devoted to hunting and natural history, were consciously preparatory to departure for the so-called “dark continent. ” In fact, he pursued medical studies for no reason other than to develop sufficient knowledge to enable him to care for himself during the rigors of African travel.

The late summer of 1871 found Selous, still four months short of his 20th birthday, landing at Algoa Bay in South Africa with a rather meagre £400 as capital for launching a career as a professional hunter in the continent’s southern interior. Within a year he had made his way to the kraal of Lobengula, the powerful leader of the Matabele, and Selous’ account of their initial meeting at the site of the present city of Bulawayo must have been typical of the general African reaction to his boyish features: He asked what I had come to do. 1said I had come to hunt elephants, upon which he burst out laughing and said, “Was it not steinbucks that you came to hunt? Why, you’re only a boy.” I replied that, although a boy, I nevertheless wished to hunt elephants, and asked his permission to do so, upon which he made further disparaging remarks regarding my youthful appearance, and then rose without giving me any answer. Eventually Selous did procure the requisite permission, and from the outset he was a marvelously successful hunter.

Using the cumbersome but cheap muzzle-loading guns of large bore much favored by Boer hunters, Selous and a Hottentot companion he called Cigar killed seventy-eight elephants from 1872 to 1874. During a four-month period alone in 1873 he obtained, together with his farmer, George Wood, some 5000 pounds of ivory while hunting along the Zambesi River: Lions, rhinos, buffalo and hippos, together will all sorts of lesser game for the pot, also fell regularly to his guns. Today his carefully maintained game lists read like a catalogue of slaughter, but it must be remembered Selous was hunting in an age when the supply of game in Africa seemed virtually inexhaustible.

Using the cumbersome but cheap muzzle-loading guns of large bore much favored by Boer hunters, Selous and a Hottentot companion he called Cigar killed seventy-eight elephants from 1872 to 1874. During a four-month period alone in 1873 he obtained, together with his farmer, George Wood, some 5000 pounds of ivory while hunting along the Zambesi River: Lions, rhinos, buffalo and hippos, together will all sorts of lesser game for the pot, also fell regularly to his guns. Today his carefully maintained game lists read like a catalogue of slaughter, but it must be remembered Selous was hunting in an age when the supply of game in Africa seemed virtually inexhaustible.

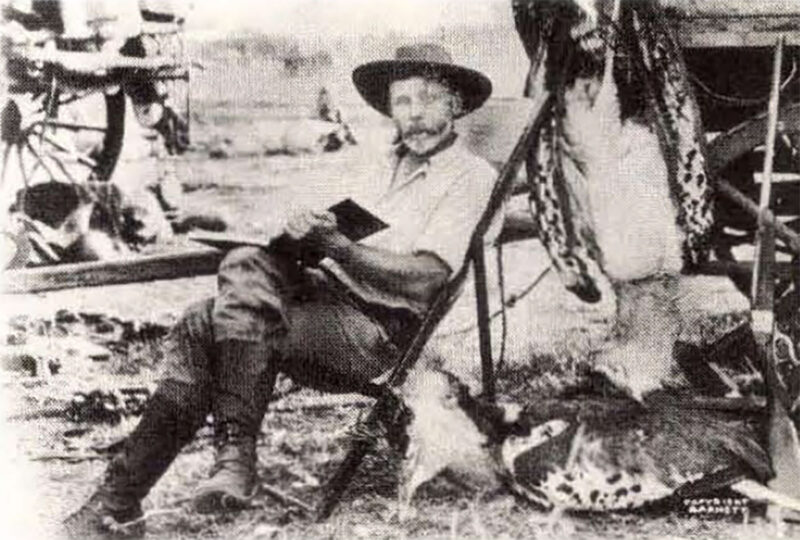

For a quarter of a century, even though the halcyon days of elephant hunting already were gone, Selous would lead a life composed of a blend of romance, danger, excitement, and adventure on the African veldt. Sometimes traveling on foot, sometimes on horseback and sometimes by ox–drawn wagon, he ventured through country seldom if ever previously seen by white men. Dressed in his highly unusual but functional outfit of leather shoes, close-fitting shorts, a comfortable short-sleeved shirt secured about his waist with a belt holding an ammunition pouch, and a bush hat, Selous was ready for all eventualities. It was, as Theodore Roosevelt would write many years later when recalling their friendship, “a wild and dangerous life, and could have been led only by a man with a heart of steel and a frame of iron.”

Selous was such a man, and his slender features hid boundless energy and dogged tenacity which enabled him to out-hunt and out-trek men who appeared at first glance to be much stronger. The fact that he earned his fame as an elephant hunter in an age when he faced conditions far more difficult than those encountered by early counterparts attests to his tirelessness and ability in the field. Certainly he was as courageous as any man, and the incidents of dangerous adventure that dotted his career were so numerous as to be almost commonplace.

He always claimed that buffalo were the most dangerous of all big game, and doubtless the basis of this contention came from a personal brush with death during an encounter with a wounded bull. After his weapon had twice misfired (an all too common occurrence with the muzzle-loading guns of the day), the angry buffalo charged as Selous fired at point-blank range. The bull, seemingly unaffected, fatally gored his horse and tossed Selous into the air as if he were a mere trifle. Once more the buffalo charged, but he managed to avoid the upward thrust of its horns even though the blow to his shoulder partially dislocated his arm. Fortunately the bull, dazed by Selous’ bullet, then trotted off into the bush.

On another occasion, when he first encountered a large herd of giraffes, Selous chased recklessly after them on horseback and very nearly broke his leg when his mount ran into a tree. When he finally recovered his horse, Selous realized that he was hopelessly lost when repeated shots failed to attract the attention of his hunting companions. Two parching days followed by bitterly cold, restless nights followed. On the third morning he awoke to discover that his horse was gone. For a lesser man this would have been fatal, but Selous continued on foot until, ultimately, he came to a Kaffir kraal where he obtained food and water. Thence he eventually made his way, still on foot, back to his party. Selous underwent many similar experiences, but for that matter so did most old African hunting hands. What set him apart from other sporting pioneers on the continent were his keen powers of observation, his diverse interests and abilities and most significantly, an incomparable ability to describe his adventures both verbally and in print.

Selous devoted the decade following his first contact with the continent almost exclusively to hunting, breaking his African sojourn for only a few months visit to England in 1875-76. In 1881, however, he returned home determined to try his hand at writing a full- length account of his experiences. He already had enjoyed some minor literary success writing articles for The Field, a popular sporting journal, and as he wrote his family in 1880: I shall go in for writing a book far which I hope to get a little money. I know that people have got goal sums for writing bad books on Africa, full of lies, though I do not know if a true book will sell well. My book at any rate will command a large sale out here, as I am so well known., and I have a reputation for speaking nothing but the truth.

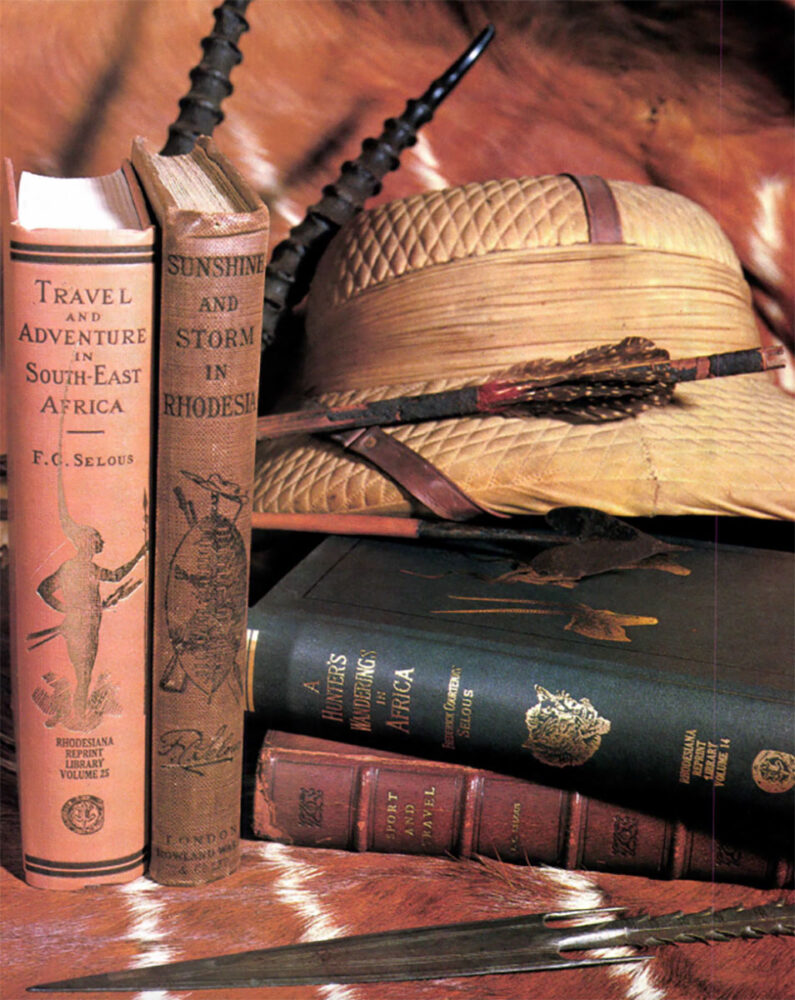

Selous finished the book in the course of a few months’ time, and the work which he entitled A Hunter’s Wanderings in Africa was an instant success. As the first significant book to cover the southern African hunting scene since the appearance of Baldwin’s account two decades earlier, it was a study of straightforward simplicity which many still consider the best of his work. Today it is recognized as one of the great African hunting classics and, like all of Selous’ major books, early editions in decent condition are prized by collectors and bring premium prices when available.

The book’s success, coupled with his decade of African experience, would shape most of the author’s subsequent career. Selous earned a good bit of money from the book and, equally important, it focused attention on him that contributed substantially to his livelihood over the next dozen or so years. Shortly after the appearance of A Hunter’s Wanderings in Africa, Selous returned to South Africa, carrying with him a number of commissions from museums and private collectors who desired trophy heads. Likewise, the renown which the book brought him created a considerable demand for his services as a guide. With such arrangements guaranteeing him a regular source of income, Selous continued his hunting excursions ever deeper into the interior, and it was during this period that Selous began to transcend his earlier role as a simple sportsman to become something more nearly approaching a Renaissance figure.

The book’s success, coupled with his decade of African experience, would shape most of the author’s subsequent career. Selous earned a good bit of money from the book and, equally important, it focused attention on him that contributed substantially to his livelihood over the next dozen or so years. Shortly after the appearance of A Hunter’s Wanderings in Africa, Selous returned to South Africa, carrying with him a number of commissions from museums and private collectors who desired trophy heads. Likewise, the renown which the book brought him created a considerable demand for his services as a guide. With such arrangements guaranteeing him a regular source of income, Selous continued his hunting excursions ever deeper into the interior, and it was during this period that Selous began to transcend his earlier role as a simple sportsman to become something more nearly approaching a Renaissance figure.

He had developed into a fine linguist conversant in a number of native languages. Similarly, Selous was developing into a superb natural historian who would, in time, be recognized as an authority in a number of areas ranging from butterflies to protective coloration in animals. Anything new fascinated him, and from his early childhood until virtually the day of his death, he chased butterflies with the same enthusiasm that characterized his painstaking stalks after bull elephants. He also became quite an explorer, and in the mid-1880s he made a number of important geographical discoveries. Some measure of their significance is provided by the Royal Geographical Society’s awarding him their prestigious Founder’s Medal in 1892, and later he would become a long-time member of the Society’s Council and an Honorary Life Fellow. Selous also continued his literary efforts, and by 1890, when his second major sojourn in Africa was at an end, he had become a fixture in the pages of The Field. His lively, eminently readable articles were just what the Victorian public wanted, and his accounts of various encounters with big game, initially in Africa and later in Newfoundland and North America, thrilled readers for the better part of three decades.

Selous’ second major book, Travel and Adventure in South East Africa, which appeared in 1893, describes his adventures from 1881 to 1890. Like his first work, it became a classic, and by the time it was published Selous was in great demand as a speaker. He had an endless fund of hunting tales and anecdotes, and in his rather unassuming way one senses that he enjoyed relating his experiences. Selous’ gifts as a storyteller were splendid, and whether he was addressing some august learned organization, chatting with cronies at a private dinner party, or relating some of his adventures to a group of small schoolboys, his audience invariably was spellbound. Accomplishments such as this gave him considerable social prominence, although in reality Selou chafed a bit in “proper” society and much prefered the simple pleasures of campfire and trail to mixing with the cream of the British upper class at fancy parties or weekends in the country.

One concession which Selou did make was the foundation of a massive collection of trophies which he housed in a hall erected for the purpose on the grounds of his home in Worplesdon, Surrey. The Selous Museum, as it was known, became a popular attraction, and parties traveled from all over Britain as well as from abroad to visit it. After his death the hundreds of trophies in the collection went, by Selous’ request, to the British Museum of Natural History. The collection was unique in the depth of its coverage of African mammals, and for this reason the recipients eventually described it in a detailed published catalogue. The Museum also recognized Selous’ many contributions in the field by commissioning a life-size likeness of him in bronze. The statue now adorns a niche on one side of the central staircase of the Museum.

At the time of the publication of his second book, however Selous was still a comparatively young man, and much of his African career still lay ahead of him. In the course of his travels during the latter part of the 1880s, even as he continued the hunting and collecting activities already described, Selous had become increasingly concerned with political matters connected with the mushrooming “scramble” for territorial holdings in Africa by the European powers. In particular, he had watched with growing anxiety Portuguese activities in and designs on Mashonaland. With any eye to forestalling Portuguese imperial designs he wrote a letter to The Times, and on a more practical basis he approached both Sir Henry Loch, High Commissioner of South Africa and Cecil Rhodes on the matter.

The result of these actions was Selous being employed as Rhodes’ agent to guide an expedition which had as its primary purpose a settled occupation of Mashonaland. While the two men were a study in contrasting personalities — Selous honest and straightforward, Rhodes devious and a master of duplicity — their common goal brought them together. Rhodes offered Selous £2000 to act as guide to the Pioneer Column, as the expedition came to be known. While this aspect of Selous’ career, and particularly the precise nature of his relations with the elusive Rhodes, is one of the most complicated and least understood facets of his life, there is little doubt that he performed his duties in exemplary fashion. Such was the magnitude of Selous’ contribution that he deservedly ranks well to the forefront among the handful of individuals primarily responsible for the opening up of Rhodesia (modern Zimbabwe).

Following his successful pathfinding activities in leading the advance of the Pioneer Column and building a road into Rhodesia, Selous left the employ of Rhodes’ British South Africa Company in 1892. With the outbreak of the hostilities that came to be known as the First Matabele War, however, he later returned to the employ of the Chartered Company for a time. Meanwhile, he had spent several restful months in England, and it was during this sojourn that he became enamored of Gladys Maddy, the strikingly beautiful daughter of a Gloucestershire parson. Their engagement had been announced before the Matabele uprising occasioned Selous’ hasty return to Africa.

Selous, second row far right, photographed with officers of the Pioneer Corps who were hired by Cecil Rhodes in the 1880s to help settle Rhodesia (modem Zimbabwe).

He proved as capable in the field in a military capacity as he was as a hunter, and he is reckoned as one of the heroes of this minor imperial conflict. Shortly after he returned home early in 1894, he married Gladys. The union produced two sons, Fred and Harold, the former of whom would die in combat in World War I exactly one year after his father’s death in the East Africa theater of the same struggle. For the moment, however, such tragedy lay far in the future, and Selous’ wandering propensities remained strong as ever. He had purchased land in Surrey, where he would eventually build his home and splendid museum, but at the time the financial burdens of such an enterprise were beyond his resources. This factor, together with his unstilled desire to roam, soon led to Selous’ return to South Africa with his new bride. As was the case with so many of the pioneering Europeans in Africa, it was almost as if the continent had an addictive effect on him. Once he had tasted its wild freedom, wonderful vistas and incomparable sport, he was driven to return again and again. Many of Africa’s early explorers experienced this strong hold, returning until the continent claimed their lives.

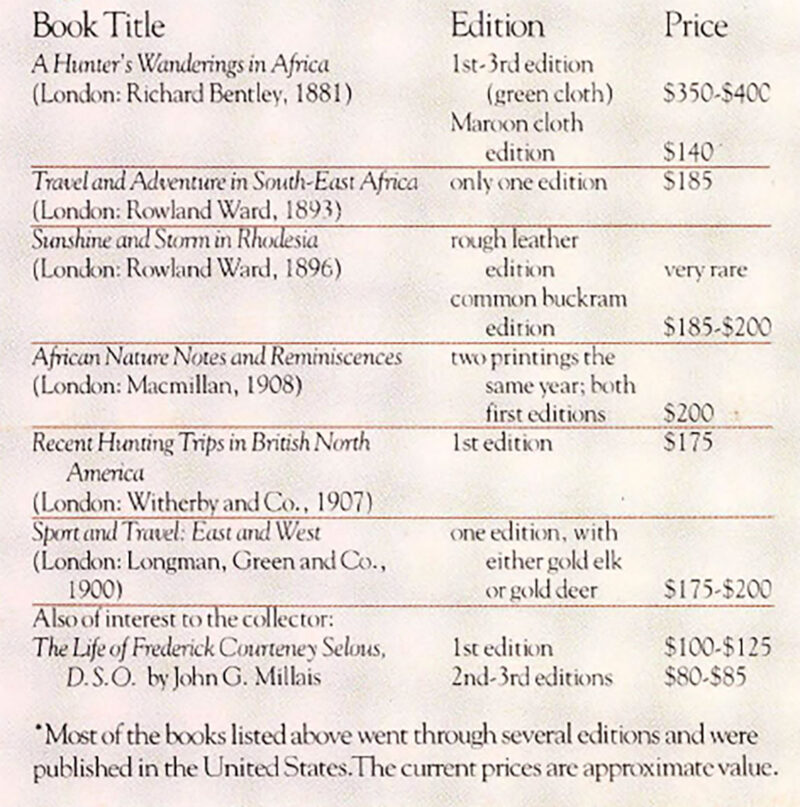

For the moment, he tried his hand as a land manager for a development and gold mining concern, and his duties on the company’s farm at Essexvale led to his becoming involved in the Second Matabele War. It was a trying, though financially rewarding, time for Selous and his wife, as he vividly describes in Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia. This book, unlike his earlier hunting travelogs, dealt primarily with military matters, but it is characterized by the same verve and feel for romance found in his earlier efforts. He returned to England in 1896, and henceforth Worplesdon would be the closest thing to a permanent residence he would know. The hunting instinct remained strong in Selous, however, and most of the remainder of his life was divided between periods at home with his family and sporting forays in Africa, Europe and America. Selous was now an accomplished and widely recognized author, whose literary endeavors became a principal source of income. He contributed to a number of the anthologies and multi-volume sporting collections that were popular at the turn of the century, regularly wrote for both sporting magazines and more serious journals and produced a number of books. Among the most important of the latter were Sport and Travel: East and West and African Nature Notes and Reminiscences. His biographer, John G. Millais, claimed that African Nature Notes was his finest book, and certainly it shows ample evidence of the incomparable knowledge and literary craftsmanship Selous brought to all his works. All remain immensely readable today, and they are one reason Selous has enjoyed such enduring popularity among collectors of both Africana and hunting books. First editions of any of his books are items of investment potential, and good copies regularly fetch from $100 upwards.

During the Edwardian era and on down to the outbreak of World War I there is a great deal of sameness in Selous’ life. His ongoing accounts of his activities in the field kept him very much in the public eye, as did his well-known and much cherished friendship with Teddy Roosevelt. He corresponded regularly with the President, visited him in the course of one of his North American hunting expeditions, and did much of the planning which underlay Roosevelt’s expedition to Africa. Indeed, Selous moved rather leisurely into the mold of a sporting squire. He enjoyed entertaining fellow sportsmen at Worplesdon, London was close enough to permit regular visits to his clubs and learned societies, and he took immense pleasure in watching his sons grow and in hosting visitors to his museum. There were always invitations for grouse hunting or deer stalking in Scotland, and the next birds’-nesting, butterfly chase, or hunting trip abroad was never far off. In short, Selous lived a sportsman’s dream during these prime years of manhood, and he managed frequent enough returns to Africa to assuage his constant longings for the continent and its rich game lands. Thanks to his active life, Selous was remarkably youthful for an individual of more than three score years, and when war broke out in 1914, he felt quite capable of participating.

During the Edwardian era and on down to the outbreak of World War I there is a great deal of sameness in Selous’ life. His ongoing accounts of his activities in the field kept him very much in the public eye, as did his well-known and much cherished friendship with Teddy Roosevelt. He corresponded regularly with the President, visited him in the course of one of his North American hunting expeditions, and did much of the planning which underlay Roosevelt’s expedition to Africa. Indeed, Selous moved rather leisurely into the mold of a sporting squire. He enjoyed entertaining fellow sportsmen at Worplesdon, London was close enough to permit regular visits to his clubs and learned societies, and he took immense pleasure in watching his sons grow and in hosting visitors to his museum. There were always invitations for grouse hunting or deer stalking in Scotland, and the next birds’-nesting, butterfly chase, or hunting trip abroad was never far off. In short, Selous lived a sportsman’s dream during these prime years of manhood, and he managed frequent enough returns to Africa to assuage his constant longings for the continent and its rich game lands. Thanks to his active life, Selous was remarkably youthful for an individual of more than three score years, and when war broke out in 1914, he felt quite capable of participating.

For a man of Selous’ vitality and patriotic inclinations, the booming of the guns of August across the European landscape in 1914 left only one recourse — active service. His age posed a potential problem, but a certificate of excellent health and dogged persistence in the face of official objections eventually led to his being accepted for active duty in German East Africa. He received a commission early in 1915 as Intelligence Officer for the 25th Royal Fusiliers. This regiment was known as the Legion of Frontiersmen, but compatriots in East Africa soon dubbed its members “The Old and Bold.” It was as remarkable an outfit as ever departed Britain for foreign service, and certainly Selous as among its most remarkable members. Its ranks included Selous’ long-time hunting friend W.N. Macmillan, an American millionaire whose size matched his wealth (his sword belt measured 64 inches); Cherry Kearton, another Selous acquaintance who had gained fame as a big game photographer; hunters such as George Outram and Martin Ryan; a servant from Buckinham Palace; half a dozen bartenders; a Park Lane millionaire; cowboys from Texas; a circus clown; stockbrokers; a lighthouse keeper; a professional strong man; and a former general in the army of Honduras. In short, “The Old and Bold” were a motley assortment of highly individualistic men, but collectively they formed an outfit in which Selous felt very much at home.

Even in such an aggregation as the Legion, his leadership qualities became immediately obvious, and in fairly short order he was promoted to captain. His inexhaustible energy made him the envy of men a third his age, and his skills in the field made Selous an invaluable asset to the 25th Fusliers. Late in 1916, his accomplishments and bravery were recognized with the awarding of the Distinguished Service Order, a distinction which gave its recipient a great deal of quiet satisfaction.

On January 4, 1917, while out on a morning reconnaissance, Selous was shot and killed as he raised his binoculars to scout an enemy outpost. The death of this kindly, well beloved man shocked everyone, and it so moved some of the askari (native soldiers) accompanying him that they went berserk with rage and routed the German forces who had fired on them even though outnumbered five to one. Thus died, clad as was his custom in khaki shorts, slouch bush hat, with a bandana about his neck, an African legend. He was buried beneath a tamarind tree with only a crude wooden cross and a pile of stones to mark his grave (a marble slab now marks the spot at Rufiji in modem Tanzania). Appropriately, the area eventually became part of the Selous Game Preserve. Selous had always been a man of action and a fervent patriot. Fittingly his death, while premature, came in a fashion and on the continent whose vast expanses he had so dearly loved.

From a modem perspective, Selous was the epitome of Victorian venturesomeness, and he was one of those fortunate few who had the opportunity to lead a full and useful life doing precisely those things he enjoyed most, namely hunting and sharing his experiences in the field with others. As a historical figure Selous is important for a variety of reasons. He represents the finer aspects of imperial sentiment, and while such outlooks are currently fashionable, it should be remembered that British expansion had its useful, even noble, aspects. His pioneering activities in Rhodesia — according to Rhodes he was “the man above all others to whom we owe Rhodesia to the British Crown ” — give him noteworthy place in the birth of today’s Zimbabwe. Most of all though, Selous was a peerless hunter.

It is in this context that he is probably best remembered, and given his abiding love for the sporting life, this is as it should be. As Roosevelt wrote in his African Game Trails, “probably no other hunter who has ever lived combined Selous’ experience with his skill as a hunter and his power of accurate observation and narration.” Selous’ own books are a lasting testament to his abilities as well as his finest, most enduring memorial. Through them the man who truly was the “Nimrod of Africa” still lives.

Editor’s Note: this article originally appeared in 1984 Jan./Feb. issue of Sporting Classics.

Well into the 19th century, most of the interior of tropical Africa was terra incognitae. Aptly styled the “Dark Continent,” wildest Africa was unknown, unexplored and unhunted. With the dawning of the Victorian era, however, all that changed. Driven by the allure of incredible hunting opportunities and the opportunity to win lasting fame through geographical discovery, intrepid individuals sought fame and fortune in the vast area where ancient maps carried notations such as “here be dragons.” Buy Now

Well into the 19th century, most of the interior of tropical Africa was terra incognitae. Aptly styled the “Dark Continent,” wildest Africa was unknown, unexplored and unhunted. With the dawning of the Victorian era, however, all that changed. Driven by the allure of incredible hunting opportunities and the opportunity to win lasting fame through geographical discovery, intrepid individuals sought fame and fortune in the vast area where ancient maps carried notations such as “here be dragons.” Buy Now