He not only left a lasting legacy of art and conservation for future generations, Frank Stick left the world better than he found it.

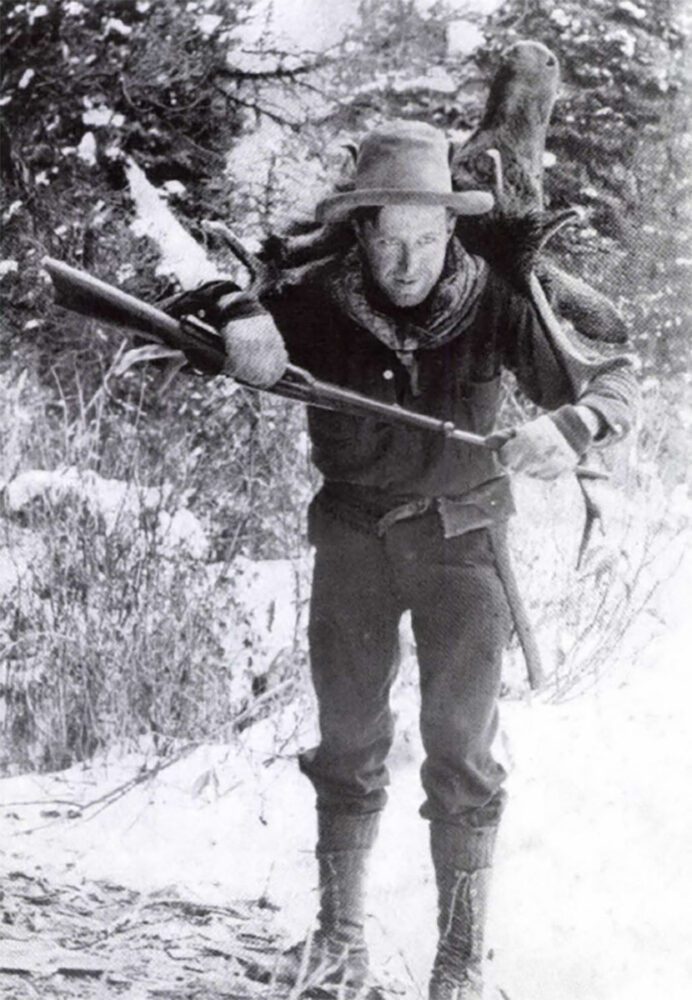

Stick packs out an elk head, circa 1909- 1970. Courtesy David Stick.

The Golden Age of illustration, which spanned the first half of the 20th century, produced some of our finest sporting artists, including Frank Benson, Philip R. Goodwin, Lynn Bogue Hunt, Roland Clark and Aiden Lassell Ripley. All of these gifted artists would earn widespread acclaim for their stirring images of hunters, anglers and wildlife. But there was another painter of this era, one every bit as talented as his contemporaries, who today remains relatively unheralded despite significant contributions not only to art, but to sporting literature, architecture and conservation. Born in Huron, Dakota Territories (now South Dakota) in 1884, Frank Stick had become an accomplished hunter and fisherman, camper and outdoor cook by age 15. Over the succeeding five years, his outdoor adventures would take him to most of the Upper Great Plains all the way to Montana, where he guided sportsmen and served a brief stint as a cook in a logging camp.

Of this period he later recalled, “And all the time I studied the forests and lakes and mountains, and the ways of the creatures that inhabited them, and put down my impressions with pencil and brush.”

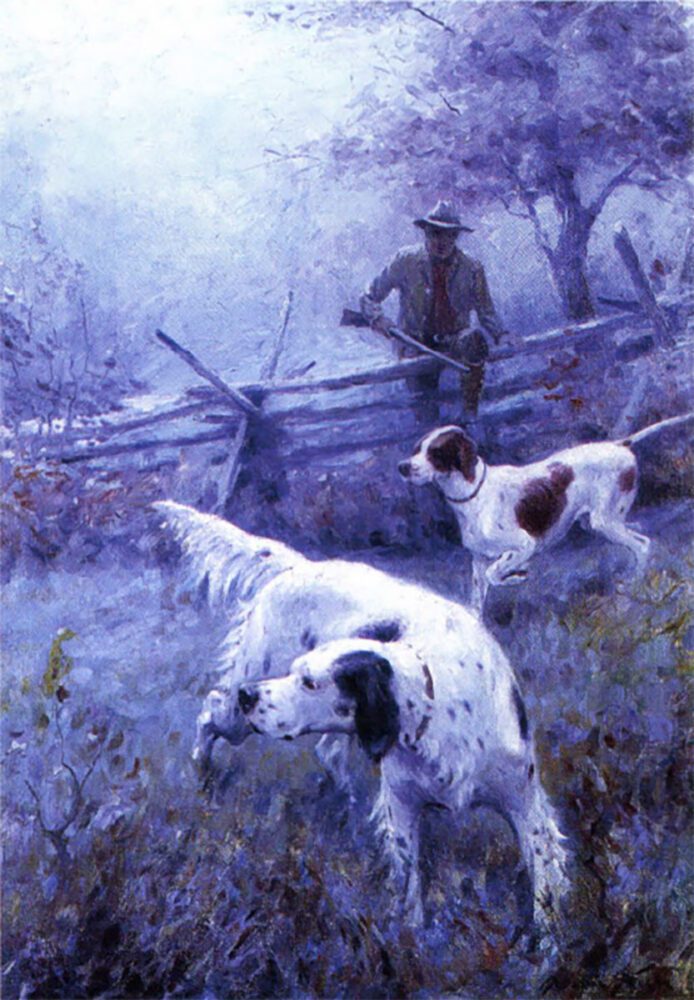

Frank Stick’s knowledge of the outdoors would later manifest itself in his paintings. They are technically correct from an outdoorsman’s perspective, with meticulous attention to detail. The hunters in his paintings are equipped with the correct packs, rifles, clothing, knives and camping gear for the particular type of game they are pursuing. The same holds true for his images of fishermen.

In 1904, Stick enrolled in a four-month course at the Art Institute of Chicago after having his first painting publish ed in Sports Afield. Even as he was developing his artistic skills, Stick began to realize he also had a gift for creating pictures in words and that outdoor magazines would pay for written accounts of hunting and fishing experiences. For the next two years, there was at least one Stick illustration and often one of his stories in every issue of the magazine.

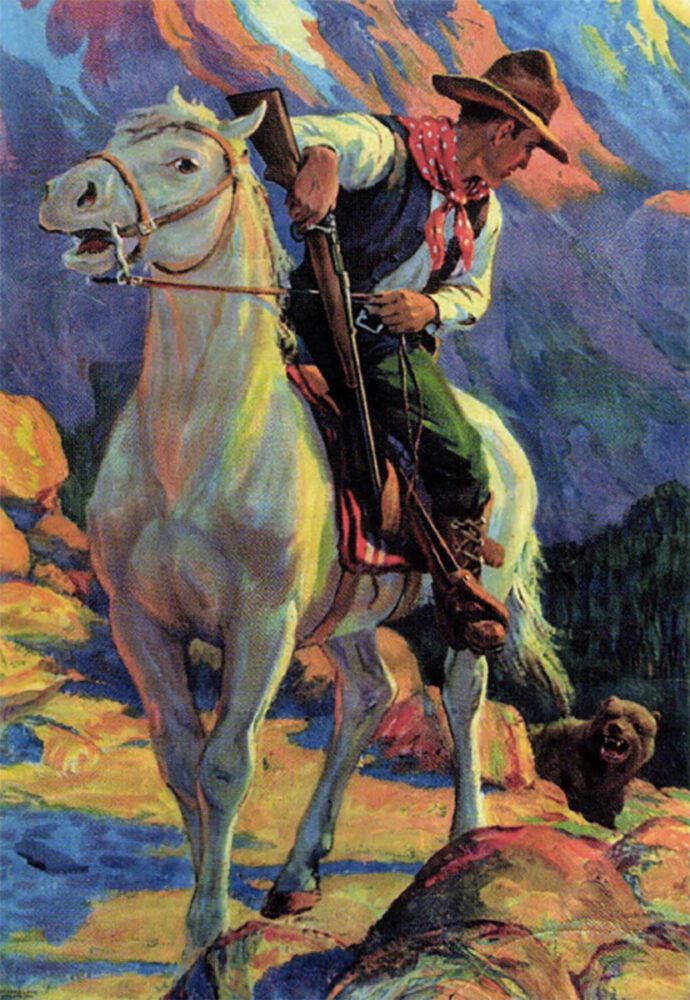

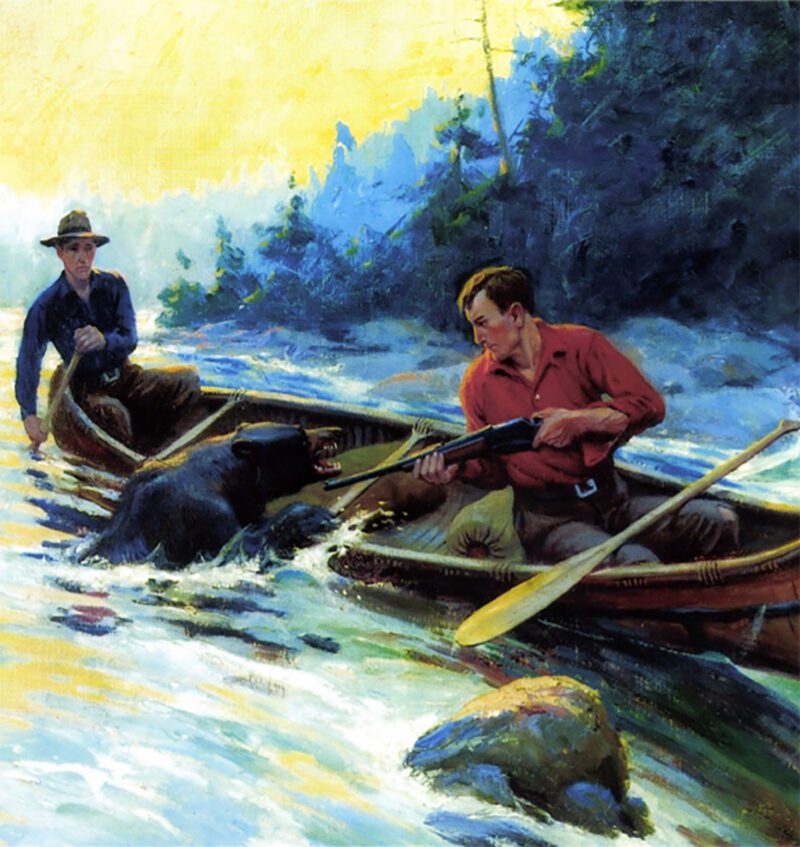

A Surprise Party, from the collection of Robert Rosenthal, appeared on the cover of Rod and Gun in Canada in 1930.

While at the Institute, Stick’s instructors were impressed with his ability, and one of them recommended that he seek advanced instruction from Howard Pyle, the dean of American illustrators in Wilmington, Delaware. In addition to Stick, Pyle counted Harvey Dunn, William Henry Dethlef (W.H.D. ) Koerner, Philip Goodwin, Oliver Kemp, Frank Schoonover and Newell Convers (N.C.) Wyeth among his many students.

In 1906 Stick began three years of instruction and criticism under Pyle. It was during this period , while sharing a studio with Dunn, that Stick wrote and illustrated for some of the most popular magazines of the day, including Field & Stream, Sports Afield, St. Nicholas, Redbook, The Saturday Evening Post and Ladies Home Journal.

Pyle’s students often used live models in their work. One of the most sought-after was Ada Maud Hayes , a petite, vivacious, 18-year-old beauty, who often sat for Koerner and was the model for his 1921 masterpiece, The Madonna of the Prairie, which today hangs in the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming. Frank and Maud, as she preferred to be called, met at a party hosted by a fellow Pyle student, fell in love, and were married in 1909. Their union produced a daughter, Charlotte, and a son, David.

W.H.D. Koerner (known to friends as Bill) and his wife, Lillian, became life-long friends of the Sticks. David Stick recalls that in addition to Koerner, his father often spoke of Dunn and Schoonover, and referred to them as close friends during their years in Wilmington.

Stick painted this horseman for a 1926 Winchester poster.

Howard Pyle’s instruction provided the guidance Stick needed to refine and master his painting technique. With Pyle’s help, Stick had established important contacts at the Eastern publishing houses and was selling both his paintings and his articles. His career was charging ahead.

After several years of living in a big city environment, the wilderness again called to Frank Stick and in the spring of 1912, he, Maud and Charlotte moved to northern Wisconsin where they lived in a cabin on a small island in Squirrel Lake. Along with a Native American companion, the family thrived on the island for two years. The Sticks looked forward to long visits by the Koerners, sometimes for up to a month. Stick helped his artist friend expand his knowledge of the outdoors and its bounty, living on fresh fish, ducks and wild rice. Frank built a birch bark canoe, and his intimate knowledge of the process became evident in several of his paintings.

Stick continued to turn out excellent work at the cabin, selling his paintings as well as his short stories to magazines and calendar publishers. By any measure he was a successful artist and his work was in high demand.

While living at Squirrel Lake, Stick’s father and brother died, and he decided to move his family to Oak Park, Illinois in order to be closer to his mother. Maud confided later that breaking up the camp at Squirrel Lake and moving to Oak Park was a much greater hardship for her husband than it was for her, for she had longed for the day when they would return to a more civilized environment.

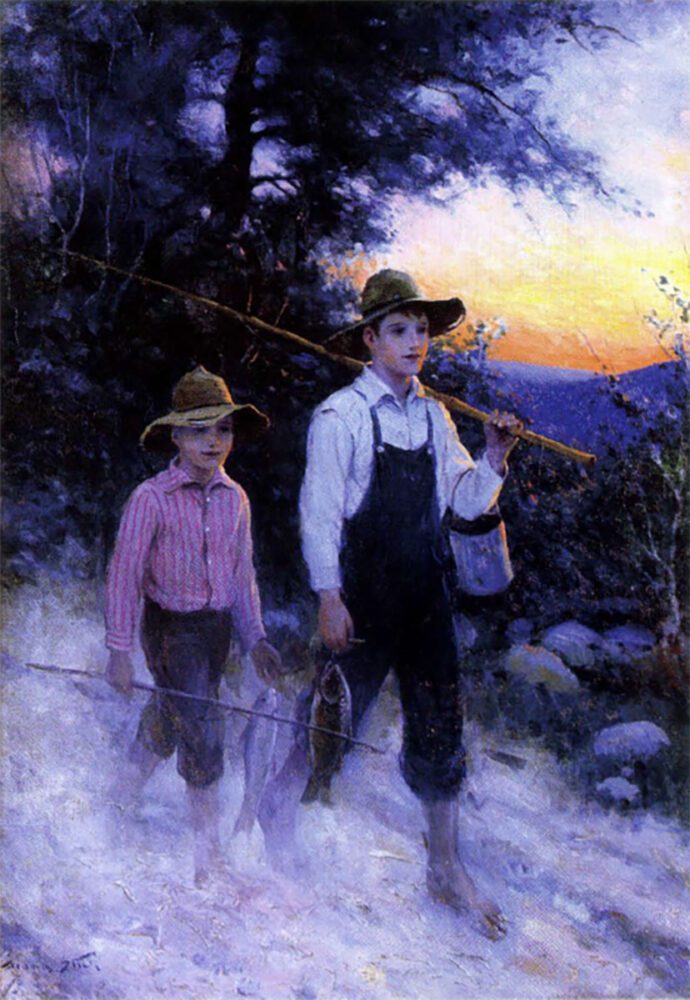

These young fishermen graced the cover of a 1924 issue of Outdoor America.

Beginning in 1916, Stick experienced two years of professional misfortune. With World War I raging overseas, Stick sold very few paintings and received no commissions for future works. By 1917, in a total reversal from two short years prior, he was broke. However, in early 1918, a large calendar company published three of his paintings and commissioned him to do12 more. It was the beginning of his climb back to the top.

The next decade brought incredible artistic and financial success to Stick. He was doing excellent work for the large calendar publishers, especially the Thomas D. Murphy Company in Red Oak, Iowa, in addition to many of the leading outdoor magazines. His paintings of hunters and anglers had made him famous. During the period from July 1919 until December 1921, the prolific artist created 153 paintings for magazines, an average of more than one per week.

Secure in the fact that he was on solid, long-term financial footing, Stick and his family relocated to Interlaken, New Jersey. The Koemers followed shortly thereafter, and the two artists headed a small art colony that would include James H. Crank, Frank Spradling and James E. Allen, all of whom would become successful artists. In 1920, Frank partnered with another good friend, famous author Van Campen Heilner, to write The Call of the Surf, the first-ever book on surf fishing. Heilner and Koerner rendezvoused whenever possible with Stick at his fishing camp in Barnegat Bay for weekend escapes from their publishing deadlines.

The Sticks also traveled often to another favorite place, the Florida Keys. It was during these trips that Frank met and developed a close friendship with Zane Grey. America’s most popular writer of Western novels, Grey was also one of the world’s greatest anglers, once owning more than a dozen saltwater world records. Besides fishing together, Stick and Grey helped to launch the Izaak Walton League of America by donating cut and articles to its magazine, Outdoor America. Stick donated about 60 paintings (thirteen of which were used as covers) over an eight-year period generating tens of thousands of dollars in income — because he believed in the organization’s conservation message.

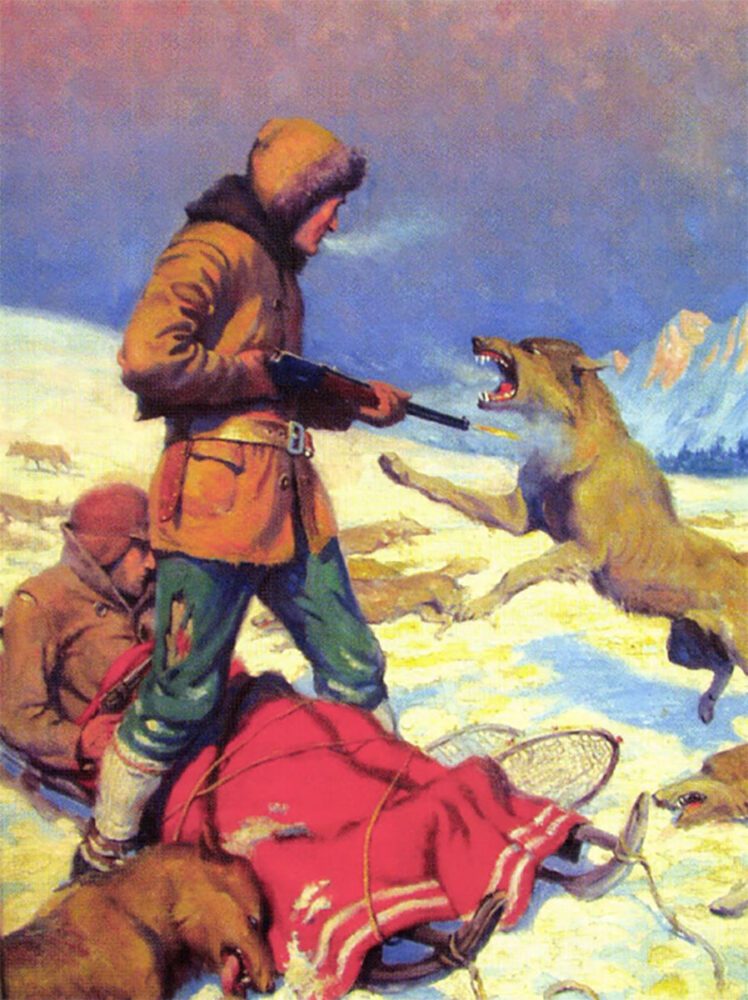

Like many of Stick’s paintings, A Critical Moment depicts an exciting encounter in the outdoors. Courtesy Bob and Mary Drummond.

Frank Stick was always searching for interesting new ideas to hunt and fish. With his surf fishing gear in tow, he and Heilner “discovered” Cape Hatteras on North Carolina’s Outer Banks in the 1920s. This part of the coast was unspoiled, and the fishing and hunting were superb. Stick’s enthusiasm for the Outer Banks spread quickly to his friends. Koerner and several others joined him in buying enormous tracts of land along the coast. At one point Stick and his associates owned 14 miles of Outer Banks real estate, part of which included Kill Devil Hill where the Wright brothers epic first flight took place. Stick, incidentally, would be instrumental in creating the Wright Brothers National Memorial.

By the late 1920s, Frank Stick was struggling with fresh ideas to paint. His main clients, the calendar companies and magazine editors, wanted him to continue producing his trademark paintings because the public enjoyed them and they sold well. At the zenith of his career, Stick reached a point where he was almost ashamed of what he was doing. In an article he wrote in 1915, he described what he was surely feeling at that point.

“The world is full of painters, yet there are few artists. There is too much talk concerning technique and handling. It is demoralizing, not only to the student, but to the professional artist. The thought underlying the picture, the thing to be expressed, this has become secondary.

“What one hears constantly in the galleries and in the studios is shoptalk on the technicalities of painting. The terms ‘well painted’ and ‘interesting’ have taken the place of the words ‘feeling,’ ‘strength,’ and ‘beauty’. The shows are full of pictures well-enough handled, some of them in color, and all of them beautifully framed, but not a half a dozen canvases in any exhibition contain that subtle something, which is described by the word ‘feeling’. The soul of the picture is lacking.

Frank Sticks’s The Last Shot was among three remarkably similar works painted by three different artists, all about the same time. From the collection of Robert Callahan.

“If I had my way, I would draw a sharp distinction between the artist and the painter. The artist develops from within. He is ruled by spirit. The painter works from a technical knowledge entirely, and his appeal, when he has any, is to the intellect only. The time has come when a majority of pictures in the galleries must be explained.”

Frank Stick did not want his work to become redundant. He feared that he was crossing the perceived distinction from artist to painter, turning out pictures for profit only. He wanted to regain control of his work and could do so only by painting from within, free of the constraints of having to please a paying client.

In 1929, Stick’s disillusionment with the art world, combined with growing concern that he was losing the feeling he considered necessary to continue turning out high-quality art, resulted in a vow to never again paint for pay. Other than one commission for his friend Laurence Rockefeller in the 1950s, he stayed true to his commitment.

Frank Stick continued to make an impact on the world over the next 36 years, but not as a profession artist. Rather, he became a successful, ecologically oriented developer, architect and conservationist. In 1933, he wrote an article proposing the creation of the country’s first national seashore park on his beloved Outer Banks. His hard work paid off when 20 years later Cape Hatteras National Seashore was established, preserving much of the Outer Banks for future generations.

A talented builder and draftsman, Stick in the 1950s created a style of home in his residential developments known as the “flattop,” which emphasized wide-open spaces in horizontal planes that blended with the sea and sky. His flat tops caught on and became the predominant local style of housing until the mid’60s. Many of those that remain have been restored by owners who appreciate their homes’ unique architecture.

The Sticks first visited the Virgin Islands in 1952, and were mesmerized by its endless snow-white beaches and blue-green tropical water. They purchased1,500 acres on St. John, which was to become their winter home. The tranquil beauty of the islands once again brought out the conservationist in Stick Teaming up with wealthy philanthropist Laurence Rockefeller, who also owned land there, the two set out to preserve the islands’ splendor. Their efforts led to the 1956 congressional authorization that established Virgin Islands National Park.

Two enterprising rabbit hunters pursue Their Christmas Dinner, a 36×27 oil on canvas. From

the collection of Charles Martignette.

Though he had given up his career as one of America’s most successful artists, Frank Stick still found time to paint. He became known as the “Audubon of fish” after spending 14 years painting more than 300 life-like watercolors of saltwater fish in all their myriad colors. These paintings were later assembled into a beautiful book, An Artist’s Catch, published by his son, David. In the 1950s and early ’60s Frank also painted stunning watercolors of the Florida Keys and Virgin Islands. The influence of Winslow Homer, whom Stick greatly admired, is evident in these masterpieces. Both artists spent time in the tropics, producing brilliant paintings of fish, fishermen, native peoples and spectacular coastlines.

Frank Stick enjoyed excellent health all of his life and firmly believed that his diet was responsible. In 1964, he was taken to a hospital in Elizabeth City, North Carolina, for a hernia operation. It was his first visit to a hospital as a patient, and his son, David, believes his father was so upset with the food that it triggered a heart attack while he was there. Stick would recover and continue to paint and exhibit his watercolors into his 82nd year, until a second heart attack ended his life in 1966. And what a life it was: He not only left a lasting legacy of art and conservation for future generations, Frank Stick left the world better than he found it.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 2005 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

Provides a detailed perspective on how fish and fishing spawned the beginning of the conservation movement. The 278-page coffee table book offers a valuable historical reference for how the predecessor to what is now known as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) began in 1871. Edited by FWS fisheries biologist and writer, Craig Springer, the book includes full color and historical images and engaging storytelling of this important piece of conservation history. Buy Now

Provides a detailed perspective on how fish and fishing spawned the beginning of the conservation movement. The 278-page coffee table book offers a valuable historical reference for how the predecessor to what is now known as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) began in 1871. Edited by FWS fisheries biologist and writer, Craig Springer, the book includes full color and historical images and engaging storytelling of this important piece of conservation history. Buy Now