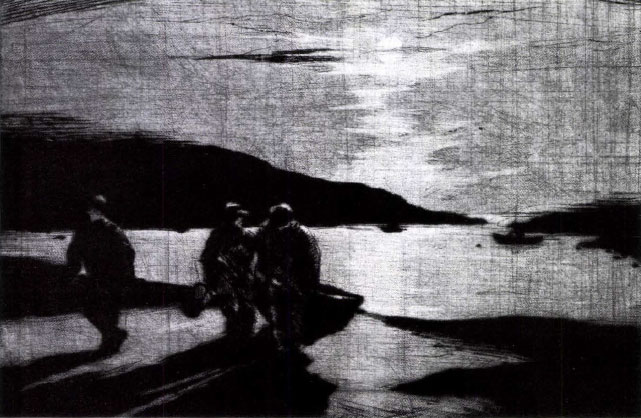

When Frank Benson decided to hang a dozen or so intaglio prints, most of sporting subjects, in the 1915 exhibition of his paintings at the Guild of Boston Artists, he unwittingly put his career on a new path and founded a new artistic genre: the sporting print.

One of America’s most highly regarded painters — a leading member of the Boston School and a founder of the select group of impressionists known as The Ten — Frank Benson was 50 years of age when he began experimenting with the etcher’s needle and the drypointist’s burin. Because he considered himself a novice printmaker, Benson was astonished by the acclaim his prints drew from critics and the general public, and he complained that for the next several weeks he was kept busy at his press, making impressions to satisfy the demands of collectors. The reception his etchings and drypoints had received, however, encouraged Benson to devote much of his time and creative genius to printmaking, and he produced an incredible 52 prints over the next 12 months.

One of America’s most highly regarded painters — a leading member of the Boston School and a founder of the select group of impressionists known as The Ten — Frank Benson was 50 years of age when he began experimenting with the etcher’s needle and the drypointist’s burin. Because he considered himself a novice printmaker, Benson was astonished by the acclaim his prints drew from critics and the general public, and he complained that for the next several weeks he was kept busy at his press, making impressions to satisfy the demands of collectors. The reception his etchings and drypoints had received, however, encouraged Benson to devote much of his time and creative genius to printmaking, and he produced an incredible 52 prints over the next 12 months.

Two years later, the first of what would eventually become a five-volume catalogue raisonné was published, and the popularity of his prints was such that most editions were sold out immediately after they became available.

Benson was often hailed as the “dean of American etchers,” his reputation being based essentially on etchings and drypoints of waterfowl and hunting scenes. Other artists — most notably Roland Clark, Richard Bishop, William Schaldach and A. Lassell Ripley, obviously impressed by Benson’s achievements in the intaglio media and by the popularity of his prints, took up the printmaking tools. Their indebtedness to Benson was obvious and freely acknowledged.

Although Frank Weston Benson will always be the master of the intaglio sporting print, we now have two artists of exceptional talent, Gordon Allen and Paul Niemiec, whose etchings and drypoints standup well to those of Benson. While continuing to make painting their primary medium, both artists have produced first-rate intaglio prints of sporting subjects. Both are admirers of Frank Benson, and his influence is clearly evident in their work.

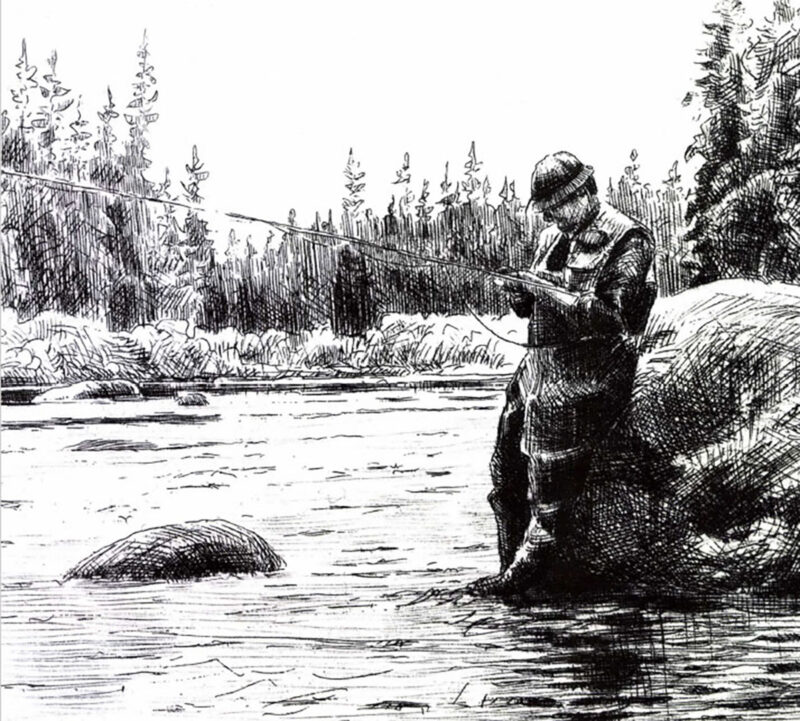

Gordon Allen has been a professional artist since his adolescence, for he was still a teenager when Gene Hill chose him to illustrate Mostly Tailfeathers. Publishers impressed by the quality and authenticity of the young artist’s drawings commissioned illustrations for other sporting books, and by age 21 Gordon had generated a reputation and an income from his art.

Gordon grew up in Maryland, where he spent all available free time hunting and fishing on Chesapeake Bay. “After graduating from high school,” he says, “every classmate went off to college while I went toa marshy island in the Bay where I spent a year guiding fishermen and duck hunters. I was outside every day, and I loved it.”

Early in his career Gordon came upon an exhibition of Rembrandt’s drypoints and etchings at the Metropolitan Museum. He was stunned by their beauty and power and challenged to try his hand at the intaglio media. He studied the basics of printmaking and was soon producing and selling prints of the sporting subjects he had been drawing as illustrations.

Although initially inspired by Rembrandt’s prints, it is Frank Benson whom Gordon calls his “guiding light.” “When I turn to an artist’s work to uplift me, to remind me of why I do what I do,” he says, ”I’m more apt to turn to my books of Benson’s etchings.”

Gordon’s appreciation of Benson’s work, he acknowledges, may come in large measure from their shared interest in sporting activities. “I now spend the majority of the year at home in coastal Georgia, where I have a world of marshes to explore. When it gets hot and sticky here, my wife and I go north to maritime Canada, where we spend the summer painting on a cool, clear river somewhere or chasing trout and salmon with a flyrod. That, too, sounds a bit like Benson. I would love in time to capture my life on canvas and paper to the degree that Benson was able to capture his own.”

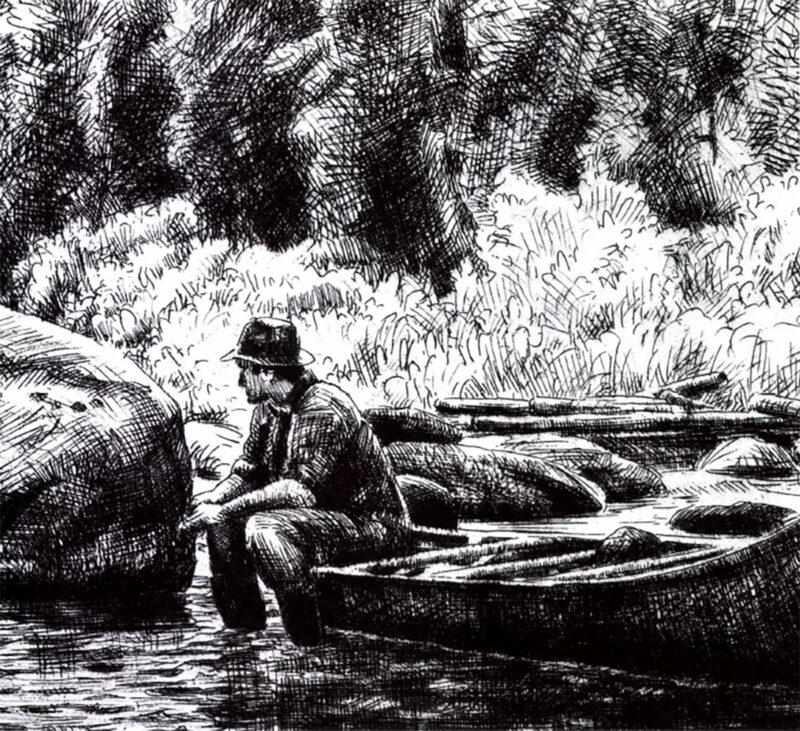

Unlike Gordon Allen, Paul Niemiec was an amateur painter for several decades while he pursued another vocation. He had earned a doctorate in pharmacology and had been working as a clinical pharmacist at John Hopkins University Hospital when, in 1988 he decided to paint full time. Like Gordon, Paul grew up on a farm in central New York, where he hunted waterfowl on farm ponds and flyfished for trout in local streams.

“I like nothing more,” he says, “than painting all day in the outdoors, whether in the midst of a vast, alive marsh or on a stretch of trout or salmon river studying the subtle composition of water, grass and sky. I paint and draw to express my personal experience and memories about themes familiar to me.”

Although he considers himself to be first and foremost a painter, Paul says that printmaking gives him the opportunity to work in the studio at a slower, more studied pace. Drypoint, which he says is like sketching, is his favorite intaglio medium. “I try to preserve the sketching looseness and movement of line that is so wonderful in Benson’s work. Such an economy of line!”

Benson’s art and teaching singularly caused me to redirect myself to a lifelong study of the elements of design through his admonition that ‘Design is everything,’ ” he adds.

I am sure Benson would likewise have agreed with Paul Niemiec’s statement on the purpose of art: “I believe that pleasing, enduring art possesses a distinctive quality of universality and timelessness achieved through simplicity, beauty and mystery, providing opportunity for participation by the viewers with their own interpretation and memory.”

It is my belief that the prints of Paul Niemiec and Gordon Allen, like those of Frank Benson, will prove to be not merely pleasing, but enduring art.

It is my belief that the prints of Paul Niemiec and Gordon Allen, like those of Frank Benson, will prove to be not merely pleasing, but enduring art.

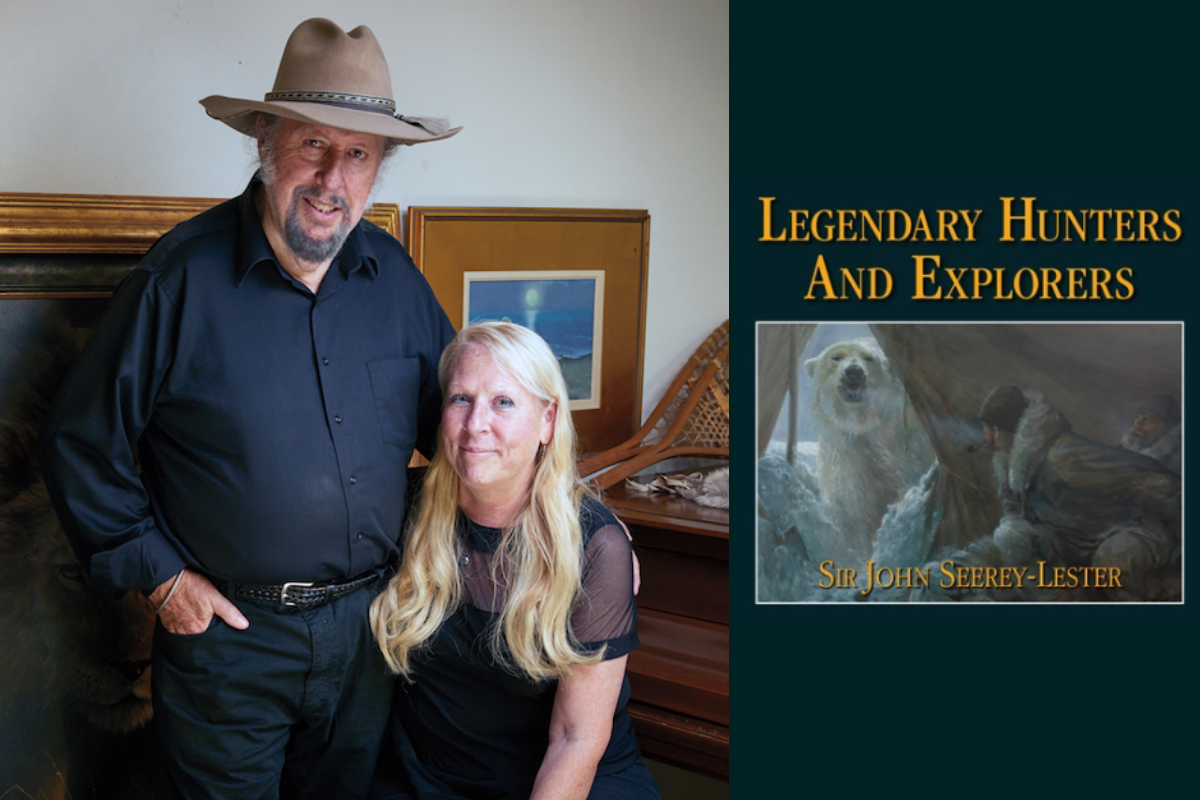

Over the past decade I have enjoyed knowing these two men, both of whom are in their mid-40s.I have had the good fortune to swap copies of my books for their prints, and my appreciation of these works has only increased with time. The illustrations that complement this article speak for themselves.

This 520-page volume contains: a critical biography of the artist; Frank Benson’s instructional essay “What Is an Etching”; an essay comparing Benson paintings and prints of similar subjects; commentary on two previously uncatalogued Benson etchings; a bibliography of books on Benson; a list of catalogs of Benson exhibitions; list of books with Benson illustrations; alphabetical and chronological list of all Benson prints; prints by Gordon Allen and Paul Niemiec, print-makers in the Benson tradition, together with their tribute essays to Mr. Benson. Buy Now

This 520-page volume contains: a critical biography of the artist; Frank Benson’s instructional essay “What Is an Etching”; an essay comparing Benson paintings and prints of similar subjects; commentary on two previously uncatalogued Benson etchings; a bibliography of books on Benson; a list of catalogs of Benson exhibitions; list of books with Benson illustrations; alphabetical and chronological list of all Benson prints; prints by Gordon Allen and Paul Niemiec, print-makers in the Benson tradition, together with their tribute essays to Mr. Benson. Buy Now