It has been suggested that Lee Jaques was the first American bird artist to put his subjects into the landscape, not merely against it.

In 1934 Jaques was given the opportunity to join a six-month museum expedition to the South Pacific on board a sailing yacht, the Zaca.

Francis Lee Jaques grew up on the Kansas prairie, fascinated by the myriad delights of nature. When he wasn’t helping on the family farm, he hunted ducks and geese in nearby creeks and marshes, and sketched incessantly. His formal schooling was virtually nil, and he was primarily self-taught as an artist, yet he ultimately became one of this century’s finest wildlife painters. He was late beginning his life’s work, nearly 40 when he was first hired as a museum artist. During the next 18 years at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, he painted 80 large diorama backgrounds, his best-known work. He also painted backdrops for habitat groups at the Peabody Museum in New Haven, the Museum of Science in Boston, and the James Ford Bell Museum at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. Roger Tory Peterson calls him “the dean of museum preparators” and credits him with bringing the diorama to its highest form of development.

Jaques was the first bird artist he ever knew, says Peterson. Still in his teens, Peterson had come to New York to attend an ornithologist’s convention at the American Museum where Jaques was a new staff member. The vast domed ceiling in the main bird hall with its multitude of flying birds, some of them painted against the sky and some of them mounted specimens hanging from invisible wires, was the finest exhibit in the museum, Peterson thought. After gazing up at it for half an hour, he remembers asking the youngish man in shirt sleeves he encountered in the adjacent hall if perhaps artist Bruce Horsfall had painted it. He was speaking to Jaques who told him modestly, “Oh, I did that.”

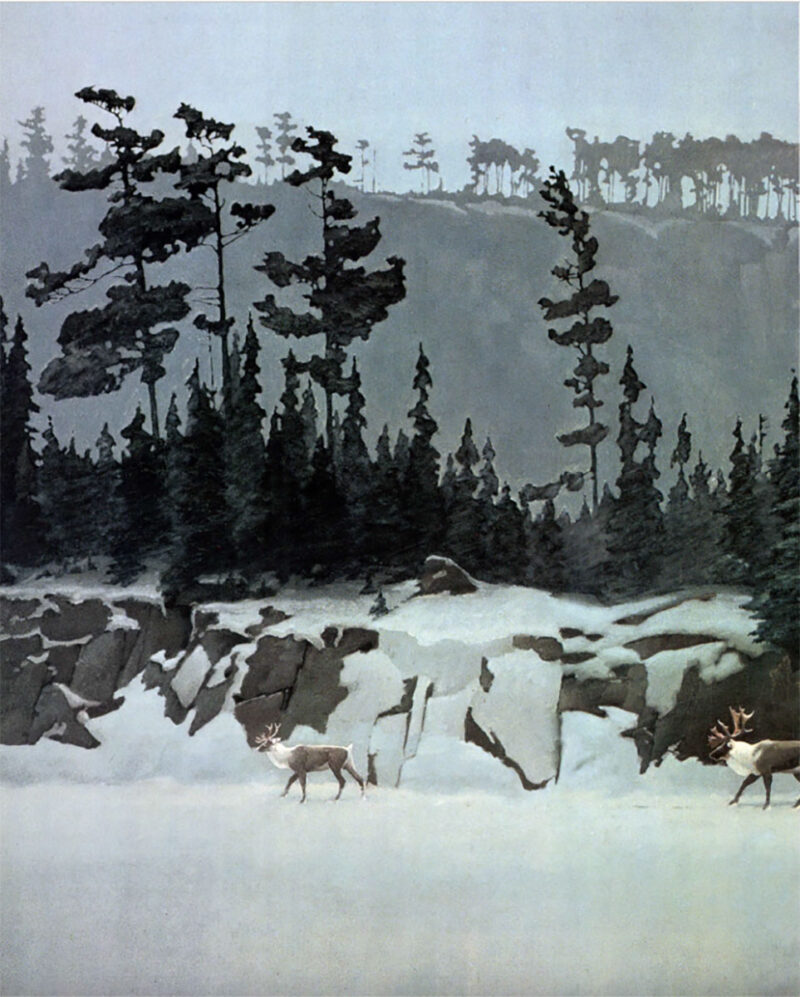

Caribou On Ice, oil on canvas circa 19405. From the James Ford Bell Museum of Natural History.

“In retrospect,” says Peterson, “I missed the real opportunity by not begging to hold Lee Jaques’s brushes. . . I would almost have given my soul to have had a year or two at the feet of the master.”

After hours, and in the years after he left the museum, Jaques also found time for the numerous easel paintings which rank as his most important contribution to American art. No one before or after him has painted just like Jaques. It has been suggested that Lee Jaques was the first American bird artist to put his subjects into the landscape, not merely against it. He was concerned with the total composition certainly, and he wasn’t a feather painter. Put simply, his canvases combine technical accuracy with enormous lyrical beauty. He painted songbirds on occasion, but he was best at ducks and other waterfowl. “The larger birds are more paintable,” he said. “They have more character.”

The Cloud, oil on canvas circa 1960s. Most of Jaques’ earlier paintings had been of birds; but he later painted nostalgic themes. Lee said that as a boy he often rested in the field in this manner and that he somehow expected to see a farmer and his team drive over the flat-topped cloud. From the James Ford Bell Museum of Natural History.

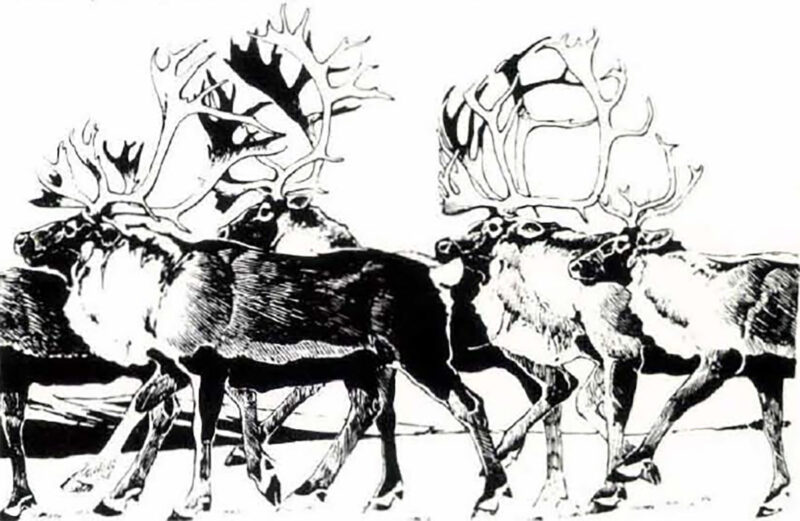

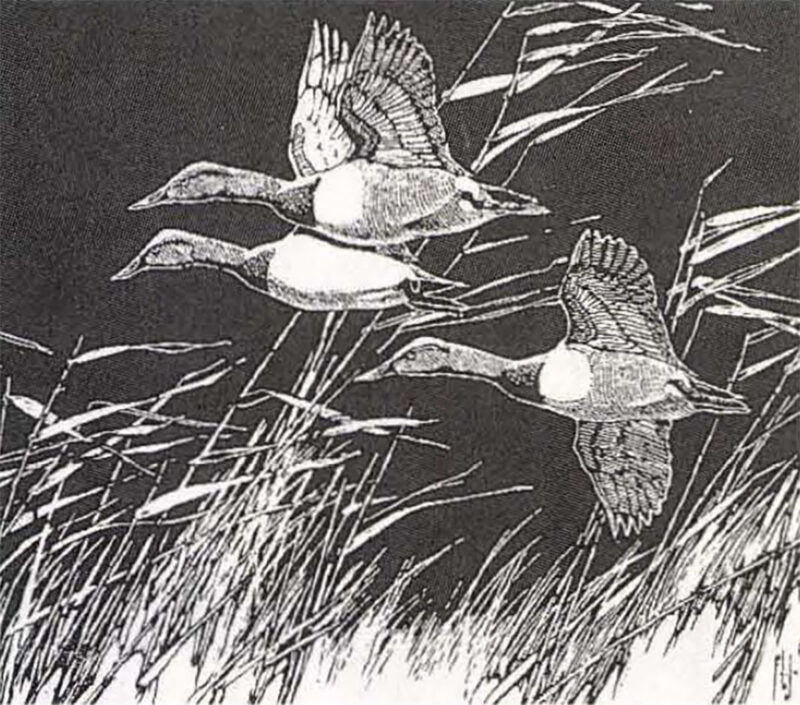

Jaques is also widely known for his distinctive black and white scratchboard drawings. He was a pioneer in this technique early in his career, and his style is often copied. Many of the 40 books he illustrated including The Singing Wilderness and The Lonely Land by Sigurd Olson, and Mammals of North America by Victor Cahalane used these pen and ink drawings. After Jaques married writer Florence Page, the two collaborated on several books with scratch board drawings that have become wilderness classics.

My husband and I met Lee and Florence Jaques in the1960s after they had left New York and moved to North Oaks on the outskirts of St. Paul, Minnesota. Lee was pricing most of his oils then at $500. If you insisted, he’d bring out a cardboard carton full of the scratchboard drawings. (His reluctance stemmed from the fact that many of these had printer’s smudges and the like on them.) We picked what we wanted for $10 and $15 apiece. He also still had a few duck stamp prints which he was selling for $35.

Jaques had been one of the first artists selected to design the annual federal duck stamp. This was issued in 1940, and he eventually made three editions of the print. The first edition was about 30 prints. When these were gone he printed a second edition, also about 30 prints. Finally, when it was certain that he had a good thing, he was encouraged to print a third edition of about 200 prints. First edition prints now sell for $7,000, and $3,500.

Francis Lee Jaques (pronounced “Jay-quees”) was born September 28, 1887, to Ephraim and Emma Monninger Jaques in a small white house next to his grandfather’s cooper’s shop in Geneseo, Illinois. His father was an avid outdoorsman who shot waterfowl for market, worked in the cooper’s shop (where the elder Jaques made butter tub), and also published articles in Field & Stream, Sports Afield and other magazines.

The busy Rock Island line ran just beyond the Jaques’s back yard, and before he started to school when he was seven, he had learned the letters of the alphabet from boxcars. Throughout his life he would love railroads with a passion second only to nature. The first sketch he made was of a locomotive.

In 1899, because of disagreement with the grandfather, Lee’s father packed up his family (there was also a younger brother, Alfred) and moved west to farm in Kansas. Lee’s sister, Emma, was born in Kansas and grew up to graduate from school and become a teacher. Lee and his brother, however, attended school only for brief periods. Instead, they worked at raking hay and cultivating com. Despite the fact that he had never entered high school, Lee Jaques was extremely well-read. Once when an acquaintance wondered aloud if anyone had ever really read War and Peace from start to finish, Jaques could say that he had.

By the time Lee was about 12 years old, his primary interest was in guns and hunting. Sealock’s Pond was a mile and a half away and “at daylight either Father or I were thereto harvest what ducks we could,” he said. Lee studied the anatomy of the birds he shot, marveled at their beauty and made sketches of them. He sent several of these drawings along with one of his father’s manuscripts to Field & Stream in 1902. They were accepted for publication, but no one made a fuss about it. At home Lee, as yet, had no glimmer of the notion that he might someday make his living as an artist.

By the time Lee was about 12 years old, his primary interest was in guns and hunting. Sealock’s Pond was a mile and a half away and “at daylight either Father or I were thereto harvest what ducks we could,” he said. Lee studied the anatomy of the birds he shot, marveled at their beauty and made sketches of them. He sent several of these drawings along with one of his father’s manuscripts to Field & Stream in 1902. They were accepted for publication, but no one made a fuss about it. At home Lee, as yet, had no glimmer of the notion that he might someday make his living as an artist.

In 1903, when it became apparent that Ephraim was not prospering in Kansas the family moved again, this time to Minnesota where Ephraim bought a farm seven miles north of Aitkin, a small sawmill town on the Mississippi River. During the winters, Ephraim and his sons cut timber which they made into rafts and floated down stream to the mills when the river opened. Lee also remembered that they chopped and hauled firewood to the courthouse in town fortwo dollars a cord.

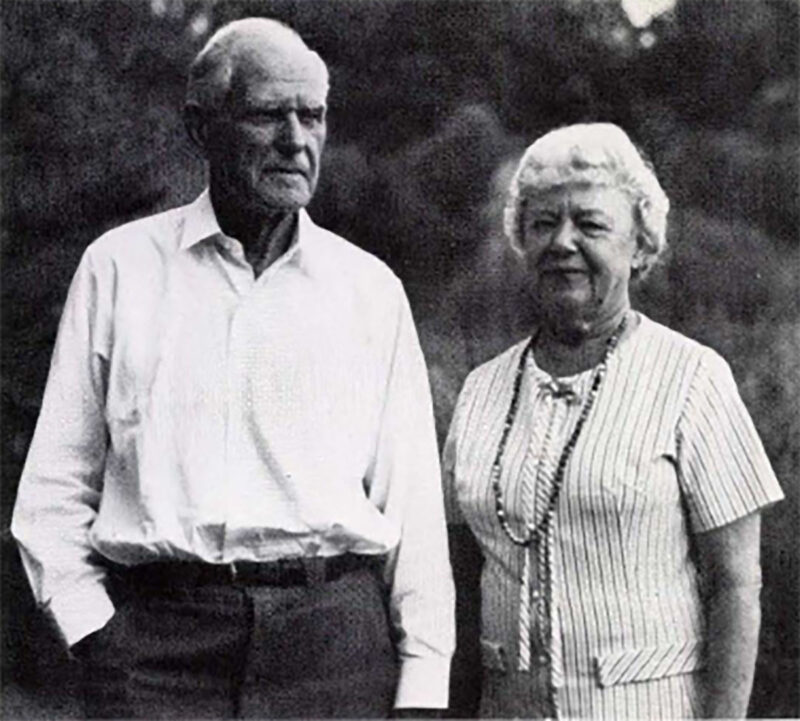

Lee and Florence Jaques, photographed in the early 1960s in their backyard at North Oaks, Minnesota. Downstairs, on the walkout level of their modest house, Lee built a superb miniature railroad he called the Great North Road. “When world crises bore too heavily on Lee,” said Florence, “he could forget r.km in his railroad world.” Photo by Noel Dunn.

Lee continued to hunt and sketch in his spare time. He also became interested in mounting the birds he shot, and found a taxidermist in Aitkin who took him on as an assistant. After a year, the taxidermist (who grossly distorted his subjects, Jaques said) moved to Duluth, and Jaques bought the shop for $10 owed him in back wages. He operated the business for nine winters, 1907 until 1916, mostly mounting deer heads for $6 or $7 apiece. It was lonely work, he learned, and he often yearned for company during the long winter evenings. Sundays he walked the seven miles back to the farm. Beginning in 1913, Jaques also worked summers for the Duluth, Mesabi and Northern Railway and later for the Duluth and Iron Range Railway. He was a wiper who cleaned fires, and then a fireman who stoked the steam engines. Sometimes he shoveled 12 to 15 tons of coal a day, and the marvelous physique he developed as a result of such strenuous work was apparent even in his old age.

Railroading fulfilled a childhood fantasy for Jaques. It also introduced him to Minnesota’s extraordinary canoe country. On a trip to an iron mine near Ely, Minnesota, he had his first glimpse of the most beautiful pine forests he had ever seen. “It was one of those times or events which change the rest of your life and you know it,” he said. Whenever he had the chance after that, he returned to vacation in this northern wilderness. In his lifetime, he paddled many hundreds of miles through its thousands of pristine lakes.

The direction his life would finally take was far from fixed, however. Deciding that there wasn’t much future in railroading, he enrolled in a course in electrical engineering in Milwaukee, and afterwards found employment at the Duluth Power Company. He was drafted during World WarI, though, and served part of his time in California where he haunted the Academy of Sciences in Golden Gate Park. Its animal dioramas were a revelation to him. Instead of being displayed in look-alike museum cases, the stuffed specimens were grouped in natural habitat exhibits which Jaques found altogether absorbing.

He returned to electrical work briefly after the war, working in Duluth’s shipyards, but he was thinking more seriously about art now. Friends urged him to try commercial art and he secured a position with the Duluth Photo Engraving Company where he drew labels for matchboxes and such, and for “dozens of useless devices to make a Model T Ford run better or hold it together.”

He also studied oil painting informally with artist Clarence Rosenkranz whom he had met during his taxidermy years. If Jaques had a mentor, it was Rosenkranz. He showed him how to mix his colors rather than using them directly from the tubes, to paint trees so that they were different species and to use light and shadow in his paintings. “I owe more to Rosen’s help than I got from all other sources combined.” Jaques said later. “I feel the debt is still far from settled, although I have tried to repay it by helping younger artists.”

Canada Geese.

While continuing to do commercial work, but with the California dioramas fresh in his mind, Jaques became convinced that he wanted to be a museum artist. He applied first to the Bell Museum of Natural History on the University of Minnesota campus, but was turned down. Lee Jaques was an unknown, and besides, the museum was only a small adjunct of the biology department. Discouraged, but still hopeful, Jaques shot for the moon next.

Nursing his disappointment back home in Aitkin, he did a painting of a black duck and sent it along with two other oils to Dr. Frank Chapman, the curator of birds at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Chapman was amazed at its accuracy. Several of his colleagues also had a look at Jaques’s work, and the consensus of opinion was that this Minnesota artist was too good a find to pass up.

Jaques was 37 years old when he boarded the train for New York in 1924; his life would never be the same again. “During the first part of my life,” he wrote, “I was solitary and withdrawn, with hardly a congenial companion; the last part has been as full and rewarding as anyone could ask for in this complicated and fast-changing world.”

The American Museum had embarked on a new and grandiose program to renovate and greatly expand their exhibits. Shortly after his arrival in New York, Jaques was asked to accompany Dr. Chapman to Barro Colorado in the Panama Canal Zone to collect materials for a tropical rainforest exhibit. From there he was sent alone in 1926 to Peru to make sketches for the 16 large oils which illustrate Robert Cushman Murphy’s two volume Oceanic Birds of South America. That same year he also traveled to the Bahamas prior to painting a coral reef group.

Jaques also met Florence Page in New York. She was a published poet and a friend of the Galloways who rented a room in their apartment to Lee. After they were married in1927, Lee took his bride to Minnesota for a three-week canoe trip. Their first book together, Canoe Country, recounts that honeymoon vacation.

Back in New York, the couple found an apartment at 610West 116th Street where they lived for the next 23 years. Jaques remained thoroughly engrossed with his museum work. He had come to New York an expert at the birdlife he had known in Kansas and Minnesota, but he was fast becoming practiced at painting birds and wildlife habitat from all parts of the world.

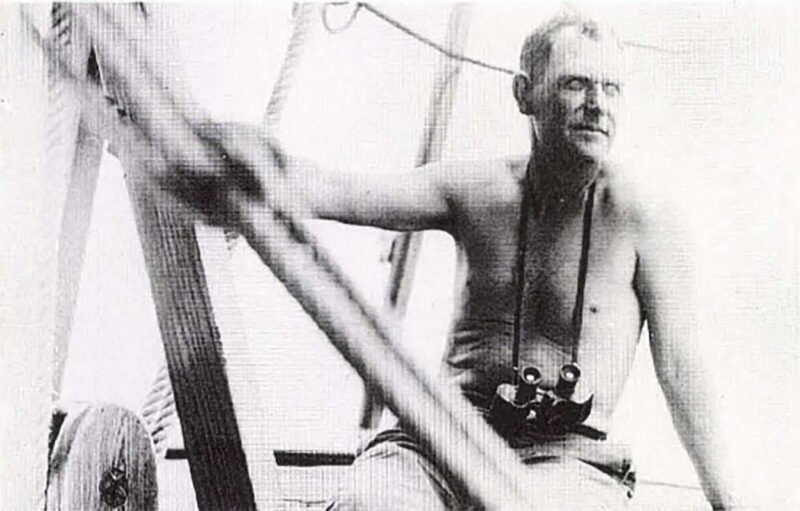

The Zaca.

In 1928, he sailed for the Artic on the Morrissey, a schooner skippered by Captain Bob Bartlett (who had been with Admiral Peary on his first successful expedition to the North Pole in 1909). The museum crew was gathering material for a sea bird group and a walrus group. Lee’s chief task was to prepare preliminary studies for diorama backgrounds, but he also assisted in collecting animals, plants and whatever other materials might be needed for exhibit foregrounds. Aboard the Morrissey, for instance, he was put to work skinning walruses. The ship’s deck was a slippery mess of blood and grease in the process, but its hold came back filled with walrus skins and skeletons. There was also a six month expedition to the South Pacific in 1934, when Jaques sailed from San Francisco with others from the museum on Templeton Crocker’s yacht, the Zaca. Lee made field sketches for habitat groups in the Marquesas, in the Tuamotus, along the Pellulvian coast, and in the Galapagos Islands. Christmas that year was celebrated on Pitcairn Island with descendants of the mutineers from the Bounty.

Occasionally, Florence was allowed to accompany the museum expeditions. She spent a month in England with Lee one spring while he made sketches for an English bird habitat group. Shortly after the South Pacific expedition she went to Switzerland with him when he needed material for a bird group that used the Matterhorn as its background.

In their private lives, between expeditions and after Lee left the museum, the Jaques traveled widely. Lee never lost his fascination with trains, and he and his wife collected railroad trips as some people collect postage stamps. One summer they rode on all the narrow-gauge railroads through the mountains in Colorado. Another year they went to Newfoundland just to cross the entire island on its only railroad.

The New York years were good ones for the Jaques, and Lee counted himself lucky to be doing the work he liked best. The time came, however, when he no longer felt he was accomplishing what he might be. The museum had grown tremendously, but a great deal of jealousy had also developed among certain of its staff. Jaques’ supervisor was certain that the artist was angling for his job (which he wasn’t), and increasingly, his work received little recognition and was sometimes even impeded. Feeling it was impossible for him to continue under the circumstances, Jaques retired at the earliest possible date that he could still qualify for a pension, September, 1942.

Golden Twilight: Baldpates, oil on canvas circa 1935. Jaques was concerned with the total composition certainly, and he wasn’t a feather painter: Put simply, his canvases combine technical accuracy with enormous lyrical beauty. From the James Ford Bell Museum of Natural History.

No longer restricted by schedules, Jaques still painted diorama backgrounds at the American Museum, but on a contract basis, and was also able to do similar work at other museums. Frequently, the Jaques returned to Minnesota where Lee was especially pleased to be asked to paint numerous backgrounds at the James Ford Bell Museum, now in a new building. In 1942, Lee and Florence also received a fellowship from the University of Minnesota Press to research and write a companion book to Canoe Country. The result was Snowshoe Country which won the John Burroughs medal for nature literature in 1946.

In 1953, when they were both in their sixties, and after having looked for a house in the country for several years, the Jaques built their first house at North Oaks in St. Paul, Minnesota. The setting was ideal to Lee’s mind. Before it was subdivided, North Oaks had been railroad builder James J. Hill ‘s 3,OOO-acre summer farm where he raised purebred livestock in the 1880s. The Jaques’ low, pink brick and white-shingled house was nestled behind a small hill that jutted up between North Mallard and South Mallard Ponds. Downstairs, on the walkout level of the house, Lee indulged his fascination with railroads in his train room where he built a superb miniature railroad he call the Great North Road. (Hill’s railroad was the Great Northern.) “When world crises bore too heavily on Lee,” said Florence, “he could forget them in his railroad world. It gave him great happiness and he never ceased working to improve it.”

Jaques paints a panorama of the Galapagos Islands on the last stop of the Zaca (Templeton Crocker’s yacht) expedition, 1935. Photo courtesy of the California Academy of Natural Sciences.

He was painting less by then, but there was usually an unfinished oil on the easel in his studio. His subject matter was also changing. Most of his earlier paintings had been of birds; but he later painted nostalgic themes. He thoroughly enjoyed what he termed his red-boxcar period when he did many railroad scenes. He also produced several semi-autobiographical paintings. Florence’s favorite among these was one she called “Self-Portrait.” Its subject is a young boy who is sitting beside his team of horses and plow, gazing skyward at a great flat-topped cloud. Lee said that as a boy he often rested in the field in this manner and that he somehow expected to see a farmer and his team drive over the flat-topped cloud.

In 1969, while he and Florence were visiting friends at a ranch in the Arizona desert, Lee had a heart attack and developed gall bladder trouble. He recovered in the hospital in nearby Benson, and the two drove back to North Oaks to resume their usual life. During the summer, however, Jaques was readmitted to the hospital. He was convalescing following surgery when he died suddenly at the age of 81 on July 24.

In his last years, he had started to write his autobiography. He wanted to call it The Shape of Things, by which he said he meant “everything one sees and senses.” “The shape of things,” he wrote, “has always given me the most intense satisfaction. Such beauty one wants to preserve — to make it available, afar as one can, to others.” His personal favorite among his paintings was the one he did last, “The Passing of the Old West.” A deserted farmstead with an abandoned hay rake he had photographed on a recent trip west takes up the foreground of the painting while long lines of migrating geese stretch endlessly across its luminous late-afternoon sky. No one, he thought, except perhaps Peter Scott in England, could have shown geese in flight so well.

Shortly after he finished it, he was at work one day on the autobiography when he tired momentarily of the task. “Time to wash the brushes now,” he wrote. It was a phrase Florence had heard often. These were also the last words he ever wrote.

The End of the Line, Canvasbacks scratchboard was an illustration for The Geese Fly High, 1939. From the James Ford Bell Museum of Natural History.

Following Jaques’s death, Florence wrote Artist of the Wilderness, her husband’s biography, which is lavishly illustrated with his paintings and drawings and was published by Doubleday in 1973. Lee’s Great North Road was dismantled and shipped to Duluth, Minnesota, where it is displayed at the train museum in the city’s historic depot. Florence also made arrangements for setting up the Jaques Gallery at the James Ford Bell Museum to which she bequeathed Lee’s artwork in their North Oaks home.

Currently, the James Ford Bell Museum has drawn on this collection and others to mount a major retrospective exhibition of 50 oil paintings, drawings, watercolors and sketches by Francis Lee Jaques that opened in Minneapolis, October 17, 1982. On January 15, 1983, it began a two year tour of the United States and Canada.

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now