He confided the happy little story that closed the 50 years between us as gently as nightfall closes day, that filled my eyes and made me smile. I’ve an idea it might foster a similar reminiscence for you.

Little, whimsical outdoor gladdenings come along now and then without bows and ribbons, just done up in the moment in brown paper and twine and presented when least you expect it. Even more happily when they pay you back with compounded interest for the 40 years that have passed since the first penny was dropped in the bank.

Maybe you weren’t the only depositor, but you had a stake in the pot, and across the years some small play in the proposition that Clay would eventuate a child of the wild.

For I think back now to when he and his sister Kristin, children of dear friends, sat as tiny folks on their mother’s and father’s laps, with Loretta and I, by a campfire those 20- and 30-something years ago, and I took them on a bear hunt. The way my uncle did for me when I was a laddy-buck as well.

Watching them follow my lead, patting with their little hands on their mother and father’s knees…mimicking the rhythm of footfall…as we stole carefully along together through a deep forest, ever watchful for bears:

Pat, pat, pat, pat…jump the creek…stop…lift your hand, shade your gaze, look right and left…pat, pat, pat…as their eyes got bigger and deeper in the firelight…pat, pat, pat, pat…shh-h-h…cup your hand to your ear, l-i-s-t-e-n…and there would be a long silence, and the cackle of a big owl from the bottom. Pat, pat, pat…hand over hand now, Kristin, Clay, climb a tree, look carefully high and low…and they would, little arms scaling the make-believe tree, by now like it was real. W-u-up! Shh-h-h! Don’t move! Did you hear that? And everybody would freeze, with them still up the tree, little hearts racing, listening until it hurt.

“BEAR! Run! Run!”

They would scream and squeal and go through the motions, little hands shimmying hard as they could back down the tree, running with us, jumping the creek, doing it all again in reverse…patty, pat, pat on the knees…fast as you could, until we all reached again the safety of where we started.

“Whew!”

Imaginary or not, I think that night the drums thumped, and there rose the chant of old men wrinkled by the prairie sun. That Clay never really came out of the woods that night, that the biggest part of him stayed there, with the bears. Held like an itinerant, scarlet leaf in the swirl of the water against the stones of a crystal stream, arrested by the red, untamed blood of his great-grandsires, the Sioux, that sprang at the headwaters of his heritage. Unafraid and in friendship with all else that was wild, and ever waiting for the rest of him—gone only of necessity in the between times—to return. So that anytime it could, he would be complete.

He would grow up a quiet child, taken mostly to himself. Would grow to manhood—it seemed—handsome, stout and straight, before he really became tolerably confident with himself within the human world around him. Even then, there remained a place of silence and withdrawal within him, which he has sheltered, held sacred and inviolable for himself. I have loved that. I could feel it and see it, then and now, and have always felt it had to do with the feather of the eagle and the hair of the bear, that waited in the woods.

The outdoors became home and sanctuary, his first and last love, and he relished every chance to be there. With his father, and, as much, with Davis, the black man and closest of family friends, who lived on his father’s farm from the boy’s childhood. Who has been by acclamation if not title, his Godfather. And I could see, over the formative years, a semblance of Uncle Remus, and Br’er Fox, Br’er Rabbit and Br’er Coon, all the beloved parables of wisdom and wiles, resident in the communal equation that makes child, man, God and wild things, neighboring kin.

The years passed and I watched the boy become the man, taking evermore to the woods of his own, to reunite with his better part. Gleaning passage and solace from its wonder and ways, searching out its secrets, trying himself against its most mystical elements, the wiles of the canniest creatures within it, until he prevailed against even the greatest.

Thereby Clay as still a young man has become a superlative outdoorsman of proper and spiritual order, ever of respect and reverence for Nature’s book and religion, sharing intuitive accord with all that live within its realm. It is rooted deeply within him, always will be, can’t be washed away, and I find it both a source of pride and humility that he would think occasionally to ask an old man along to share.

So that the last day of turkey season this year found us together, after Mister Longspurs had accepted sweeter offers, deep in the woods, by a stream. As the drums thumped lowly and the bloodwater eddied amongst the rocks, leaving a timeless message before wending their way ahead, and we sat there and talked quietly of trees and skies and waters.

And it was there he confided the happy little story that after all the seasons fits so well, that closed the 50 years between us as gently as nightfall closes day, that filled my eyes and made me smile. I’ve an idea it might foster a similar reminiscence for you. If not, I hope it will.

He told me of a little slew he had found, in the creek, that flowed placidly among standing trees, and hooked beautifully around at its head. That was vibrantly green in spring and gloriously red in fall. So that wood ducks loved it, even then, but he had wanted to make it better. Back it up, so they would feel at comfort and come the more. So they could hunt there, sparingly, he and his girlfriend, Jamie, with his black Lab “Panther,” but as much, just to have the birds there to watch year through.

You see, Clay’s father is a self-made man of property and means, but he brought his son up stoically, never coddling or showering blessings upon the boy, but ascribing him to resilience on his own. One day, I thought, as we sat there, and he told me this, Clay would have great impoundments, be a member of a grand and exclusive waterfowling club, perhaps, of his own. Now, though, he was happily poor. When you don’t have a backhoe, or a dozer, you work with what Nature gives you.

“So I gathered up a bunch of sticks, and threw them together, where the creek narrowed,” he told me, happiness in his eyes, “made a makeshift dam. Packed it with mud best I could. Made some rough duck boxes, scattered them around.

“And the little run grew a little, swelled a little wider and deeper, and spring came, and Jamie and I hid there and watched several hens, weaving through the standing trees with their new broods. One with thirteen,” he said brightly.

He dropped the conversation suddenly, froze, and for the next five minutes we watched deer steal by.

“But my little dam leaked, and I couldn’t get it right,” he lamented, when he continued. “The water kept seeping down.”

It was then, with wildwood wisdom and youthful resourcefulness, that he had summoned the idea of engaging a professional. Someone with the means, experience and know-how to bring things right.

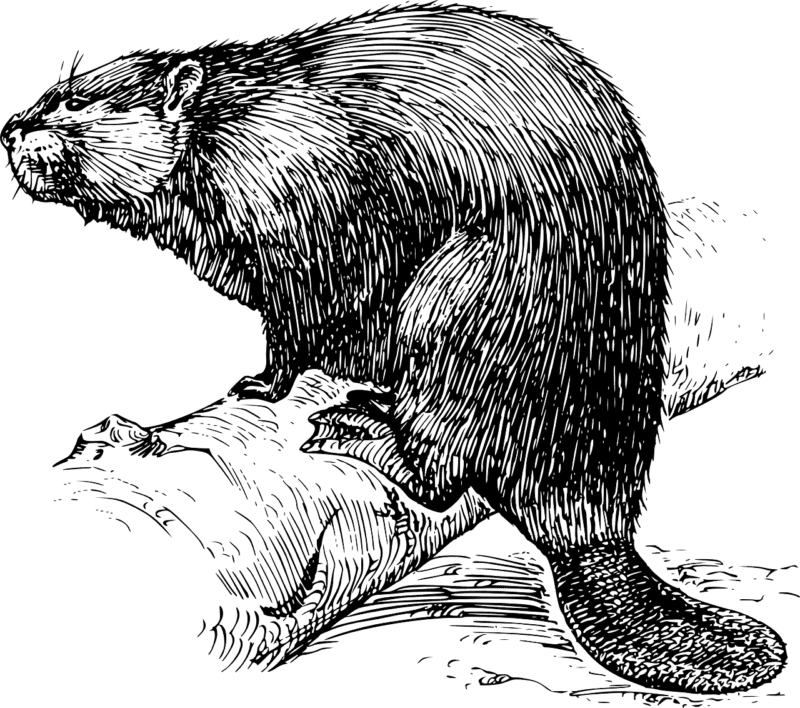

With no money but a wealthy poke of forethought, he went to a neighboring farm. Where at the moment another hydro-topographical engineering project had over-run its contract. After a week or so, live-trapping a big ol’ lady beaver. Turned her loose in his little slew. And everybody was happy. Including the late and afflicted landowner.

“Me and Jamie named her “Flo,” he said with a grin.

“Not ‘No-Flo?’” I said kiddingly, “cause that’s what beavers do.”

He grinned again, like he’d been had.

“No, just ‘Flo,’” he said.

And I’m sitting there with my legs clamped, trying not to pee on myself, ’cause his daddy not distantly has spent a Wall Street fortune trying to eradicate beavers from that whole end of the farm.

But he’d better not bother Clay or the beaver about it, or he’ll have me to deal with, even if he is bigger than I am.

Well, Flo, professional that she was, went to work and shored up the dam in about 48 hours, now has it on a fixed maintenance schedule, with dedicated plans to flood additional acreage.

“The water level’s up eighteen inches,” Clay tells me proudly. The beaver’s found heaven, built a lodge and become downright tame; Clay has a duck impoundment, is building a blind like Nash had on Beaver Dam, is planting wild rice, water potatoes, smartweed and every other kind of forage he can conjure up for both the ducks and the beaver, the birds are pouring in, the deer come to drink, green herons secret among the inundated stumps, the frogs and the water snakes tentatively co-exist, red-wings nest there, Great Blues roost there, and Clay and Jamie spend hours there as well, snuggled up and absorbing it all, peas in a pod.

Me? I think it’s biblical, the most enterprising and harmonious vessel of homemade symbiosis since Noah floated the Ark.

Unless Flo gets so protective of paradise she lends misery to Panther’s retrieving duties, all bodes well.

Only body ain’t happy, maybe, is his Dad. Whom I’ve known for many years, and whom Clay’s now mimicking with perfect timing and inflection, sending me to gales of stifled laughter,

“We gotta git rid o’ that beaver. If that thing has babies, we gonna have beavers from here to next Monday. They gonna…you let him get in my pine trees, and it’s…He’s…”

“She’s not a ‘he,’” Clay tells me he corrected, before resuming his mime.

“He’s already plugged up the pond pipe…” (“He…I mean, SHE, did not…” Clay had emphatically countered.)

Which actually “he” did, but which Clay has carefully covered by digging an inconspicuous and temporary drainage ditch to carry off the flow—no pun intended—until he can figure out how to unplug the spill pipe, and negotiate the beaverage within amicable boundaries.

Stay tuned. The compromise that mitigates this one figures to be classical.

Meanwhile, me and Davis are cackling still, have lit a candle and gone down to the river to pray. For Clay and the beaver.

Despite his considerable self-worth and business acumen, we figure this is one deal the Ol’ Man will likely have to eat (appreciatively), whether he ever admits it or not.

I love boys that grow up wild. Glad I’m one of ’em. Ain’t chu?

This is a full-color edition of the very first Boy Scouts Handbook, complete with the wonderful vintage advertisements that accompanied the original 1911 edition, Over 40 million copies in print!

This is a full-color edition of the very first Boy Scouts Handbook, complete with the wonderful vintage advertisements that accompanied the original 1911 edition, Over 40 million copies in print!

The original Boy Scouts Handbook standardized American scouting and emphasized the virtues and qualifications for scouting, delineating what the American Boy Scouts declared was needed to be a “well-developed, well-informed boy.” The book includes information on: The organization of scouting, Signs and signaling, Camping, Scouting games, Description of scouting honors and more. Scouts past and present will be fascinated to see how scouting has changed, as well as what has stayed the same over the years. Buy Now