Daylight promised its coming in typical Delta fashion. Scudding clouds that produced off-and-on splatters of heavy, iced rain drops riding a north wind that hardly qualified as gusts. Still, that wind was more than ample to toy with denuded oaks, easily making eager fingers brittle. Sunrise, at least its visual announcement, would face a challenge. It eventually rose to that challenge, however, and a perfect winter day unfolded.

Minutes earlier, four of us had abandoned a pickup and trailer in favor of an ATV and slogged through adhesive topsoil still pasty from flood waters that had plagued the area for seven months. The odor was that of decaying leaves and crop stubble and of wet, thick mud. A sour pungency, but pleasant in a way known well to the outdoors type. Ephemeral, yet poignant enough to occasionally dawn over the shadowed twilight of recall. No crops had been planted the previous spring. Four-wheeler headlights confirmed that Josh was executing his approach from another road on the opposite side of that field. The ATVs then took on the temperament of bulldozers, riding over peripheral tangles that had grown amok.

Backwater Teal by David Hagerbaumer, watercolor, 22 x 30 inches.

Presently, the object of our efforts unfolded. A shallow slough. Rimmed, guarded by and festooned with poplars and oaks. These barren forms suggested anxious waiting, their skeletons moaning at chills that disturbed them. Simultaneously passive and active. An esoteric setting and pronounced portrait of a Delta duck hole, this was. Waterfowl frequented it.

And this land, this Delta as it is regionally labeled—what and where is it? Specifically, the hunt outlined here was just outside Onward, Mississippi, 30 miles north of Vicksburg, this city generally considered the southern terminus of the Delta. It stretches northward, the Mississippi portion ending at the Tennessee border. It consists of approximately five million acres give or take, and covers 7,000 square miles. Stiff facts, these are, yawning during their struggle to become interesting. But they are an accurate and viable description of the where. It is in the description of what that protracted complexities arise.

This is a land of history, a nostalgic and mysterious land. A land of plenty and a land of scarcity. A land some consider exhibiting signs of machination. It is rich, with perhaps the most efficacious farming foundation in the United States. But when coupled with the often-angry inclinations of that mighty river to the west, it can create a beggar. It is a land of beauty and austerity, a land that welcomes and scowls, a land that embraces and rejects. But above all, it is a land of romance, a land that captivates, grasps at the passerby, entangles the more curious with an invitation to stay longer and learn more.

The Delta is home to artists of varying propensities. Home of B.B. King and the Blues, a prescribed trail dedicated to this music running south to north throughout this grand alluvial experience of flat earth. It is home to writers—Willie Morris was from Yazoo City, Shelby Foote from Greenville. It is home to Hollywood celebrities—Morgan Freeman lives in Charleston, at least part of the time. Country Music artist Charlie Pride is from Sledge. This land holds the Grammy and Blues Museums. Leland proudly claims Jim Henson and his Muppet, Kermit the Frog.

And the Delta’s reach was and still is sufficient to stretch its tentacles of allure within touching distance of William Faulkner. He hunted the eastern portion of the middle Delta and eventually found himself miles south and west along the Big Sunflower River, in the big woods. Most of those woods are now only phantoms of hearsay, but they were then—with Faulkner, pipe in hand and sitting within the conflation of common folk around a fire at hunting camp—settings of pedagogical and inspirational value, a muse that would later burst into creativity. Old Ben, introduced in The Bear appears suspiciously akin to Old Reel Foot from one of those campfire stories Bill heard.

Nick Tarlton keeps a visual on circling mallards. A gear bag and “mud” stool are appreciated while in flooded timber.

Then came sunrise and legal shooting time and a shotgun blast from my right that was followed by a thudding splash on the slough’s surface. One mallard. But the transfusion of gaudy greens and muted grays from a frowning sky didn’t stop. Actually, it increased. A half-dozen here; 10 over there. Even more circling. Those committed dangled orange legs and webbed feet and cupped powerful appendages commonly known as wings, which are in truth signal flags of wildness and the freedom of commutation minus earth-bound restrictions.

Those tools, those wings, are the things of dreams, of imagining. They are the apparatus of haunting swishes created by their disturbance of a silent sky. They are, these wings and their whistles, likely the most invigorating aspect of duck hunting, the one thing that, through remembering, fills sleepless nights and too-early wakeups. The thing we seek before the hunt, the thing we contemplate afterward.

For the next few seconds a din of shotgun rumbles permeated an otherwise hushed serenity—save those wing beats. Those rumbles seemed an affront. There were sprays of success from well-made shots. Some groans by the one who failed to get cheek to stock and follow through. I was occasionally among those groaners. When I did as I knew to do and instinctively put all the scrambled pieces of the shotgunner’s art in their proper order, a charge of Kent Fasteel 2.0 20-gauge No. 4s cast from a nimble little Mossberg SA-20 did the chore for which they were designed. An inexpensive and fully reliable unit, this Mossberg is. I liked thoroughly what I was holding and shooting. The 20 was completely adequate for these conditions, and I determined to use it again—and soon—in similar exercises.

Duck holes in flooded timber don’t normally require huge decoy spreads. A simple collection with a motion unit or two should suffice.

At some point, when a lull in the frenzied goings-on occurred, I found myself rambling through remembered pleasantries. I recalled another day, removed from here by time and geography. Geographically, I was in the Delta on that recollected day, but much farther north, almost to the Tennessee line. Chronologically? My beard had only a sprinkle of gray back then. And back then, there had never been a heart issue to stop by for a visit. No cataracts or spinal repairs begging attention.

Back then, I was with Mike Boyd at Beaver Dam, a locale much touted by Nash Buckingham. That day was not unlike this one I was currently living. The surroundings, however, contrasted. Rather than a hidden slough, Beaver Dam was more expansive. A lake. Tall cypress, knees encircling trunks, were scattered about. A boat ferried us to a blind, complete with heater and cooking gear. The latter, at some unspecified time after daybreak, would give up sausage and eggs and biscuits. Hot coffee, too, its steam rising with such ferocity as to produce a squint from the one holding a cup. I was using a 12-gauge O/U that day, a Remington 3200. Lead shot—back then. We, according to my host, had passed Nash Buckingham’s old blind, “Just right around that bend.” My imagination began a rambunctious series of resplendent sojourns.

Kinton waits with two of his mallards and the Mossberg SA-20.

I imagined Mr. Buck and Horace over there in that blind. I imagined mallards and gadwalls dropping in by the hundreds. I reproduced—in my rambling brain—the thud of Bo Whoop. Even thought I heard Mr. Buck’s quiet accolades regarding Burt Becker, these whispered to Horace and followed by soft chuckles of affirmation.

I imagined a rumble reverberating from the Limb Dodger, its steam whistle declaring eminent arrival at the Evansville station—nightfall hinting from the west across lonely fields and big timber and suffocating openness, nightfall that would soon encapsulate deer and bears and quail and waterfowl. Through that eye inside an energized brain coaxed to extremes by the surreal, I saw Horace scuffle nervously about in an effort to get the mule and wagon moving in the proper direction to extract Mr. Buck from the train and deliver him solidly to camp; goose dumplings and cornbread waited. Grand imaginations, these. Then someone whispered, “Take ’em.”

Up there, just slightly off to my right, were mallards. Five or six. One particular drake was already dropping through cypress crowns, those crowns seeming to seek respite from the gray, the sameness, from winter’s choke hold. The first shot missed, but the second was more productive. There, in proximity to Mr. Buck and Horace and Bo Whoop and this blind, lay that mallard, soon to be retrieved by a skilled Lab and placed at my feet. That mount holds a revered spot in my trophy house.

And again someone whispered, “Take ’em,” this time from that duck hole near Onward. The immediacy of this situation demanded I abandon Beaver Dam, bid good day to my enterprise of fraternity with the greats from another time and generation. But not of another persuasion; we, all of us past and present, were and are duck hunters. More mallards, and this time one was particularly opportune. A charge of steel from the 20 and the bird lay motionless, splendid even in that posture.

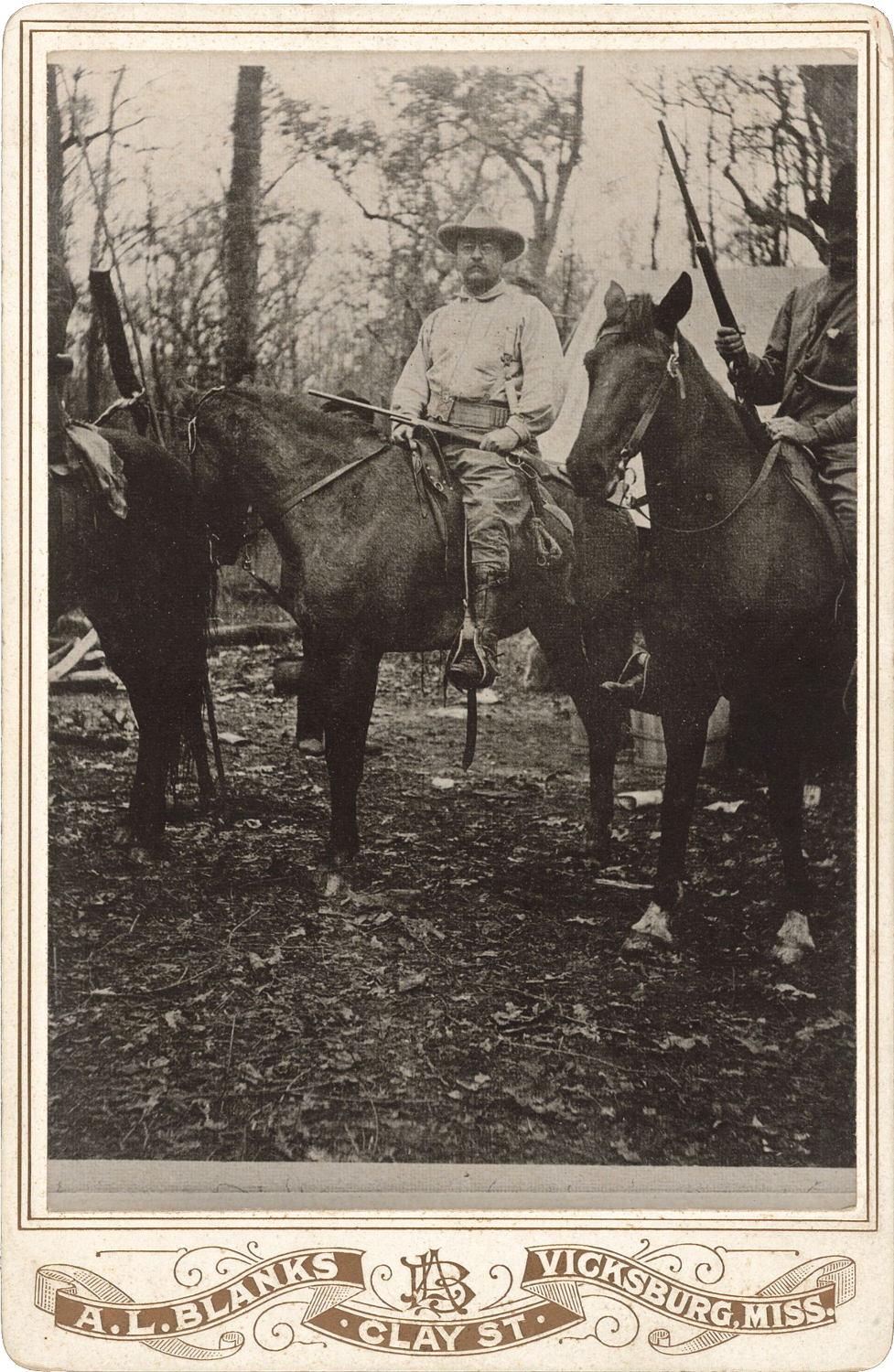

Presently, Josh or Nick or Conrad or someone was pointing. I pulled the ear plug from my left and heard soft-spoken conversation occurring among my comrades. “Right over there in that stand of woods.” The pointer was still pointing. I determined that this exchange referenced a famous bear hunt, Onward, Mississippi, the center of said activity. It was that hunt made by President Theodore Roosevelt and Holt Collier, an intriguing duet. And we hunters were no more than a long throw from where this drama was performed.

Holt Collier alone possessed ample celebrity to make one tremble with delight. A former slave, he joined in service to the Confederacy, distinguishing himself in frequent action and solid success as a military spy. But perhaps Collier was and is best known as a hunter, a skilled houndsman. He is credited with taking some 3,000 bears throughout an illustrious career. And right over there, he and the President proffered a commanding mix. Such a coupling is the thing of legend.

The year was 1902. Roosevelt had come to Onward for a bear hunt; Collier would be his guide. The story, now fully famous, outlines Roosevelt’s failure to take a bear during several days of slogging and horsebacking through big timber and swamps of the South Delta. Collier, unwilling to allow the President’s suffering through more indignities, took the hounds and caught a bear. This bear he tied to a tree—right over there. The sportsman that he was, Roosevelt refused to shoot.

Thanks to the subsequent publication of a cartoon depicting the President’s refusal, this story has been given a long life. And we all likely know it. That cartoon ultimately resulted in what is perhaps the most lovable cuddly toy in history, the Teddy Bear. And its genesis was, well…right over there. I was again mesmerized. Perhaps Holt Collier leaned against the same tree from which my pack dangled. Perhaps his hounds scuffled through this very slough. Perhaps Roosevelt’s footprints were directly beneath the soles of my waders, now knee-deep in Delta water. Perhaps. A thrilling possibility regardless of scant probability.

Then, more ducks. They first circled, made a wide pass. Ten maybe, could have been more, elected to check out the decoys the next time around. Five shotguns joined the choir in harmony with nature’s realities, and four drakes dropped. I figuratively patted myself on the back, for that fourth plummeted from the 20 I was toting. Just short of naked-limb cover of an oak he was when the little shotgun sang baritone. I can be an abysmal shotgunner at times, but not this time. We counted to determine our progress on a limit. Two remained.

The Mossberg SA-20 and Mossberg Waterfowl in 12 gauge performed flawlessly.

These two came in haste. And there were only two, both drakes. They cupped and wobbled directly in front of Josh and me. One note from Josh’s A-5, one from my Mossberg. “Limit.” This pronouncement was well timed but unnecessary. We gathered ducks and gear for another trip through the muck. Tomorrow would not be a hunt day. Rigid schedules among the party precluded another morning on a duck hole until later. That later would be the day after tomorrow—Thursday.

Conversation, not in the proper fashion of gentlemen, was shouted rather than spoken, this due to that noisy rattle of a diesel and the ATV’s tortured progress through obstinate mud and brush. That shouting turned toward deer more than ducks. Josh suggested we join him Thursday afternoon behind the levee for a deer hunt—after we had indulged ourselves in duck doings Thursday morning. We agreed.

The levee to which Josh referred is part of a massive system flanking the Mississippi River and is longer than the Great Wall of China. It, in theory, contains the Big Muddy within specified boundaries and keeps it from flooding homes and farm lands along that huge churning body of turbid liquid. It doesn’t always work as hoped; flood waters often creep into and from tributaries and inundate lands outside the levee. Regardless, those lands lying inside the levee are rich and productive and otherworldly. Some huge whitetails live there, though often temporarily displaced by rising waters.

And rising waters outside the levee were what incarcerated thousands of acres of the South Delta the same year as this hunt. The struggle began in late winter prior to the hunt and, when we were there the following January, those waters had only recently receded. That caused great stress on the deer herd, which gathered on the sides of that levee for some scarce bit of sustenance and over-crowded security. Still, limited hunting was being conducted, and there we were with an invitation to participate.

Thursday morning held little promise. Powerful gusts tormented sodden ground and tired trees and winter’s bleakness. The thermometer was rising from its earlier slot that had indicated a too-warm night. We went to a duck hole just the same. Decoys out and waders in the shallows, we waited. And called. The skies were void—other than an eerie blush on the horizon and those roiling clouds of angst suggesting storms within 24 hours. A common regimen in this part of the world, when winter heats rather than chills and fronts scoot in with menacing vigor. Perhaps an hour or two of late afternoon in the deer woods would materialize, but conditions would become dire given time. Weather prognosticators said so. We abandoned the duck hole, more for practicality than from disillusionment. Such is the life of a duck hunter.

Friend Bryce was down from Vermont, participating in his annual dose of Southern hospitality. This hospitality is medicinal. He was to fly home Saturday. But with unkind weather predicted, we opted to cut the week short by a day and explore the possibilities of changing Bryce’s ticket so that he could get out Friday, maybe ahead of the storms. That logistic accomplished, we put on rain jackets and orange. I tugged a sleek little Ruger No. 1 in 9.3X62 from behind the truck seat. While having received little use in hunting procedures at this point, it had become a part of me, an object of affection. Simply fondling this rig and daydreaming of distant game fields produced amplified satisfaction.

And we saw deer. Bryce more than I as it turned out. But one I saw worked his way into my very core. He presented quietly in the far end of a green field, swaggering as he walked, stopping occasionally to tangle antlers in overhanging limbs along the field edge, nibbling a bit on the green that protruded from wet soil of his home turf inside the levee. He was magnificent. Blocky, muscular shoulders and neck. Sacrosanct in a way. And those antlers—wide and heavy and chocolate. Six points only, but worn proudly. Had nutrition been abundant during spring flooding, perhaps he would have been substantially more decorated. Still, he was a grand stag. I watched.

Then there he was—60 yards and broadside. Certainly legal and more than acceptable. Surveying his surroundings. Authoritative. I considered his hardships, admired his resolve and cunning. I thanked him in whispers for his grandiosity and nodded my respect. The 9.3 lay motionless across my knees. Another day or another year.

We left before daylight Friday, the airport 50 miles ahead. And with Vicksburg twinkling in the rearview mirror, I thought of this grand anomaly known as the Delta. Regardless of the mental gymnastics I had participated in while there, I shall never actually see William Faulkner sitting around a campfire. I shall never actually share Mr. Buck’s blind with him nor actually take a duck with Bo Whoop. And I shall never actually know whether or not I stepped in the tracks of Teddy Roosevelt or hung my pack on the same tree that Holt Collier used as a prop. But I do know without question that while there, I saw the fingerprints of God.