The .300 RUM (Remington Ultra Magnum) is a monster. But it attracts a lot of attention and gains a lot of fans. Why?

Because this is America, where bigger is better! Seriously, there’s a lot of truth to that old wisecrack. Cartridge development over the past 150 years has been mostly about getting more power and velocity in shoulder-fired rifles. The biggest step forward came with smokeless powder starting around 1890. That led to significant improvements in bullet materials, construction and form. Then came ever-larger capacity cases, and voila!, say hello to the .300 RUM.

Remington launched this beast in 1999, it’s first .30-caliber. For decades Remington was satisfied with its 6.5mm Rem. Mag., 7mm Rem. Mag., 8mm Rem. Mag., .350 Rem. Mag. and .416 Rem. Mag., leaving the all-American .30-calibers to Winchester, Weatherby, H&H, Norma and even Dakota. But when the .30-378 Wby. Mag. and .300 WSM popped up—well, I guess Remington couldn’t resist jumping in. Finally.

The towering .300 RUM, at right, puts the .30-06 and .300 Win. Mag. in a whole new light.

Good jump. Using a fat .404 Jeffery case 2.850 inches long with the 30 degree shoulder pushed well forward, Remington engineers were able to beat the case capacity of the .300 Wby. Mag. by 13 percent and the Win. Mag. (which you can read all about on this 7mm vs. 300 Win. Mag. blog) by 20 percent. That means it can throw the same size bullets about 200 fps faster than the Win. Mag. and 100 fps faster than the Wby. Mag. with increased recoil to go with it.

So why do you want a .300 RUM? Let us count the ways.

1. You want to impress your friends.

Just showing them a .300 RUM cartridge should do the trick. Let them fire your rifle to cement the concept.

2. You like big thumpers.

When firing a 200-grain bullet at 3,185 fps, this super magnum will kick you with nearly 32 foot-pounds of free recoil energy. Compare that to 21 foot-pounds recoil from a .30-06 shooting a 180-grain bullet in a typical eight-pound rifle.

3. You want to shoot long and flat and hard.

Zero the 200-grain Nosler Accubond at 250 yards and it will be just two inches high at 100, 2.87 inches low at 300, and 12 inches low at 400. At 500 yards, the bullet will still be hauling 2,543 foot-pounds of energy. That’s more oomph than a 168-grain bullet from a .30-06 carries at 100 yards.

4. You want to deliver more than 1,300 foot-pounds of energy at 1,000 yards.

The mass and sleek shape of the 200-grain Nosler give it a drag resisting BC of .588. Combine that with the 3,185 fps launch speed and you’re delivering major energy at crazy distances. There are even heavier, higher BC bullets out there to increase this long-range whomp.

5. You like packing big, heavy rifles with long barrels.

Seriously. The .300 RUM needs at least a 26-inch barrel to take advantage of its fire-breathing potential, and a 28-inch is even better. Add a bit of stock bulk and weight to soak up some of that recoil. A broad butt and comb help spread the recoil over a greater area of your shoulder and face for added comfort. Include a muzzle brake and recoil really shouldn’t be a problem. But be careful. This will compromise reason #2 in this list.

If you like the kick of a .30-06, you’ll love the wallop of a .300 RUM.

The length of the .300 RUM brass is exactly the same as the .300 H&H belted magnum. This means it requires a magnum-length-action rifle. Remington rebated the rim of the .300 RUM so it wouldn’t have to increase the bolt face diameter and receiver diameter of its M700 actions. Some shooters point out that this rebated rim could cause the bottom bolt edge to slide up and over cartridges while trying to push them from the magazine. I haven’t seen this happen. I haven’t heard any RUM shooters complain about it, either, so it may be more theory than reality.

What isn’t theory is the power, punch, recoil and downrange reach of the .300 RUM. Personally, I don’t have any need for a .300 RUM, but that doesn’t mean you don’t. In America, bigger is still better, and freedom of choice is still an option. Let’s hope it stays that way.

For more from Ron Spomer, check out his website, ronspomeroutdoors.com

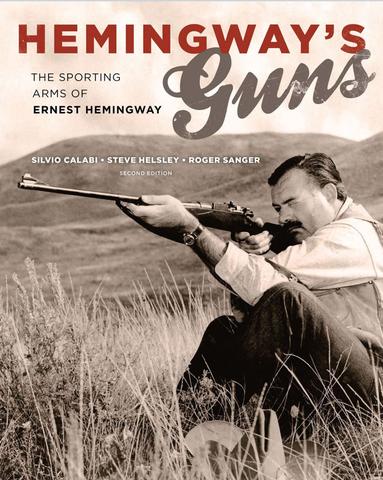

Ernest Hemingway’s friend A.E. Hotchner once described a “yellowed four-by-five picture of Ernest,” shown him by Hemingway, “aged five or six, holding a small rifle. Written on the back in his mother’s hand was the notation, ‘Ernest was taught to shoot by Pa when 2½ and when 4 could handle a pistol.’”

Ernest Hemingway’s friend A.E. Hotchner once described a “yellowed four-by-five picture of Ernest,” shown him by Hemingway, “aged five or six, holding a small rifle. Written on the back in his mother’s hand was the notation, ‘Ernest was taught to shoot by Pa when 2½ and when 4 could handle a pistol.’”

Firearms and shooting infused Hemingway’s existence and thus his writing. He was a member of his high-school gun club and went to war when he was eighteen. He hunted elk, deer, and bear in the American west and went on two extended African safaris, which figured hugely in his writing and changed his life. To the day of his death, Hemingway remained an avid hunter, first-class wingshot, and capable rifleman.

Following years of research from Sun Valley to Key West and from Nairobi, Kenya to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, this volume significantly expands what we know about Hemingway’s shotguns, rifles, and pistols—the tools of the trade that proved themselves in his hunting, target shooting, and in his writing. Weapons are some of our most culturally and emotionally potent artifacts. The choice of gun can be as personal as the car one drives or the person one marries; another expression of status, education, experience, skill, and personal style. Including short excerpts from Hemingway’s works, these stories of his guns and rifles tell us much about him as a lifelong expert hunter and shooter and as a man. Shop Now