Williams Creek National Fish Hatchery, situated amid the ponderosa pine-studded hills of the White Mountains of eastern Arizona, harbors gold: the only captive Apache trout brood stock in existence.

This hatchery, one of 70 other national fish hatcheries, turns 80 years old this year. It’s a product of the New Deal era—a hatchery built on Apache lands under the auspices of the White Mountain Apache Tribe for the express purpose of raising trout for fishing. Trout fishing, then as now, helps fuel a rural and tourism-based economy in the White Mountains.

The Apache trout, as odd as it may seem, is a fairly recent arrival to the hatchery given that it sits so closely juxtaposed to native trout’s habitats. Recognizing the trout swimming in their streams as something special, the tribe closed off reservation waters to fishing approximately 30 years before the Endangered Species Act became law in 1973. The tribe was the first conservator of Apache trout.

Though this rare trout wasn’t described for science until 1972, hatchery biologists made early attempts at creating an Apache trout brood stock. Getting wild fish accustomed to captivity is difficult. Those attempts fell flat until 1983, by which time commercial fish food had become more refined such that captive wild fish take to it easier. The existing Apache trout brood stock turns 35 year old this year. Those captive fish descend from the original fish brought on station more than three decades ago.

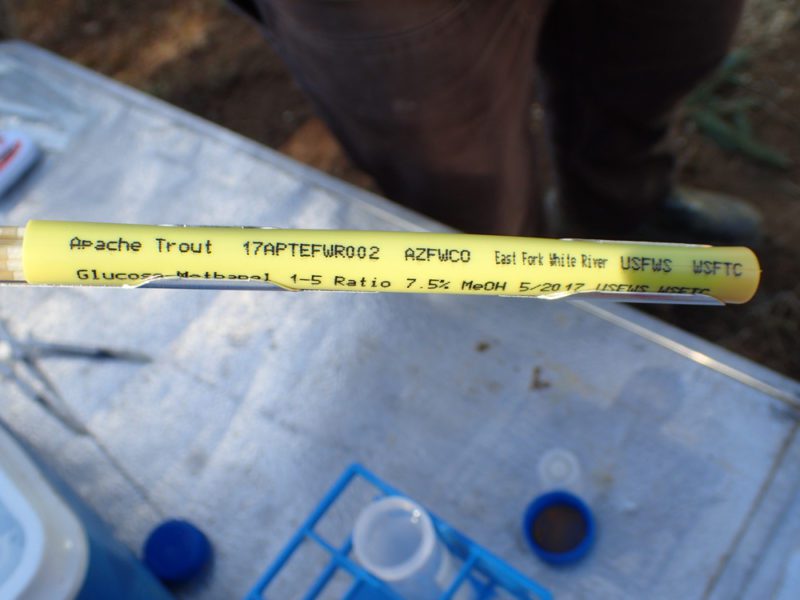

Apache Trout sperm label indicates to be frozen at Warm Springs Fish Tech Center in GA. Photo Courtesy: Jennifer Johnson-USFWS

To bolster the brood stock, the biologists have turned to what sounds like science-fiction: “cryopreservation.” It’s a big word for this: they collected sperm from wild Apache trout and froze it.

It’s science-fact. Hatchery biologists along with staff from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (Service) Arizona Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office and White Mountain Apache Tribe collected sperm from wild Apache trout from the East Fork White River. Under the guidance of Service biologist Dr. William Wayman at the Warm Springs Fish Technology Center in Georgia, the team of biologists collected and froze sperm from several individual Apache trout this past spring.

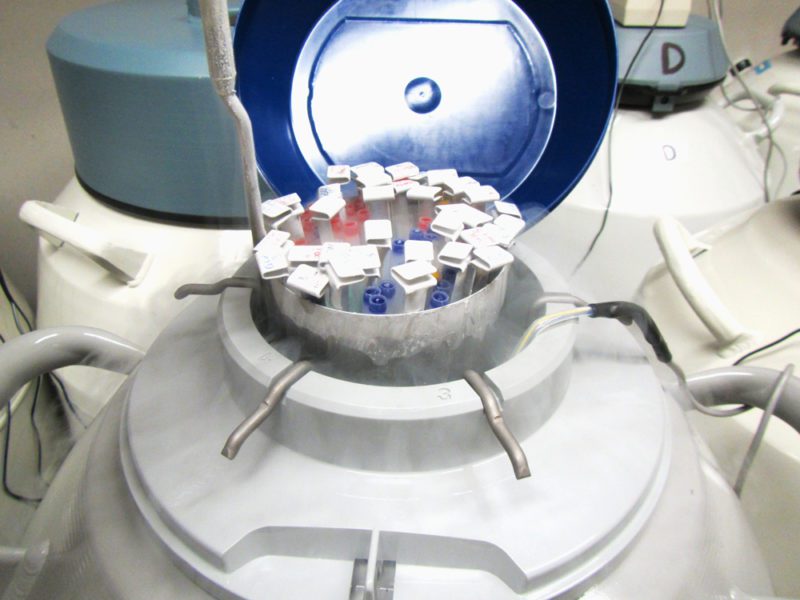

Straws containing Apache-trout sperm are frozen in vats of liquid nitrogen at Warm Springs Fish Technology Center Warm Springs Georgia. Photo Courtesy: William Wayman-USFWS

Gathered and stored in clear straws the approximate size of a coffee stirrer, the sperm now reside in vats of liquid nitrogen at -321 degrees Fahrenheit in Georgia in permanent storage, locked in time. And there it will be stored until it’s needed for spawning at the hatchery in November.

“We expect cryopreservation to boost our brood stock,” said hatchery manager, Bruce Thompson. “Cryopreservation reduces the likelihood of spreading disease that comes with having live fish brought in from the wild, not to mention the savings—a savings in space, in time and in money—by not having to keep wild male trout alive on the hatchery.”

The hatchery stock originated from the East Fork White River—it’s a rare lineage of a rare trout, says Service geneticist, Dr. Wade Wilson. He’s stationed at the Southwestern Native Aquatic Resources and Recovery Center in Dexter, New Mexico. Wilson has expert knowledge of trout, having worked with two other species native to the American Southwest, the Rio Grande cutthroat trout and Gila trout.

Williams Creek National Fish Hatchery biologist Russ Wood preps Apache trout milt for freezing. Photo Courtesy: Jennifer Johnson USFWS

“Cryopreservation at least preserves the genetic diversity of the males, and the main advantage is that we can infuse wild genetics into the captive fish with great ease,” said Wilson. And the approach will be disciplined, as Wilson has developed a plan for the hatchery staff to ensure that each pairing yields genetically robust Apache trout offspring that exemplify the East Fork lineage. Having collected the genetics from the wild male fish and the captive female Apache trout, data from Wilson’s shop will steer captive spawning this autumn. Those offspring will be future brood stock.

Dr Wade Wilson a geneticist at the Southwestern Native Aquatic Resources and Recover Center in Dexter New Mexico guides brood stock management for Apache trout. Photo Courtesy: USFWS

The whole idea of freezing and thawing a living organism gives flight to the imagination, even if it is a single cell. Cryopreservation hasn’t been use yet for Apache trout brood stock management, but the concept isn’t new. The method is common in the livestock industry and has been used for decades.

Jennifer Johnson of the Arizona Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office shocks Apache trout while White Mountain Apache Game and Fish staff net the fish.

For rare, native trout, “it’s like backing up your data” says Thompson. “You store off-site what’s precious, and we’re confident that this is good for Apache trout conservation.”

Craig Springer, External Affairs, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Southwest Region