About 1000 AD, crusading knights returning from the Holy Land brought back wild tales, algebra, oranges, hashish, harem girls and steel so special they named it after the city where they found it — Damascus.

History suggests Damascus steel was not Arabic at all but East Indian wootz, dating from more than a thousand years before Europeans took notice. Indeed, Arab traders plied their commerce from China to Spain so it’s not hard to imagine camel caravans clanking along with “Damascus” bar stock heading for forges in Syria.

No matter its origin, it works something like this: Take a half-inch pine board and bust it with a 20-ounce framing hammer, no problem. But try the same on a half-inch sheet of plywood, and you will be beating all day long. But while half-inch plywood sheeting may have four layers, five at best, layers in a Damascus blade are limited only by time and art.

No matter its origin, it works something like this: Take a half-inch pine board and bust it with a 20-ounce framing hammer, no problem. But try the same on a half-inch sheet of plywood, and you will be beating all day long. But while half-inch plywood sheeting may have four layers, five at best, layers in a Damascus blade are limited only by time and art.

Two layers of steel — or steel and iron, traditionally — one hard, the other pliant, hand-hammered yellow hot. Fold it, hammer again, fold again, do the math. Two to four to 16 to 32 to 64 layers…128? Keep the forge hot and the hammer busy. Shape, grind and polish the bar stock, swab it with acid and the grain pops out, a grain finer than the finest gunstock wood.

Most of us are familiar with Damascus gun barrels, sometimes called “twist steel,” wherein two, three or sometimes four ribbons of Damascus bar stock were twisted and wound around a tapered mandrel at high temperature, then hammer forged into a beautifully patterned seamless tube. Once again Europeans got the technology from the Middle East when thousands of Damascus-barreled muskets were abandoned by the Turks after their defeat outside Vienna in 1683.

Europeans “reverse engineered” what they found and within 30 years forges from Spain to Sweden were manufacturing Damascus barrels. But production reached high art in the gunworks of Liege, Belgium. Before World War I shut down production, and Whitworth and Krupp compressed fluid steel made Damascus barrels obsolete, Liege barrels were exported around the world, some with shotguns attached, others not, up to 200,000 some years. Even some early models of the famed Parker shotgun came with Belgian twist-steel barrels.

But subsequently, Damascus barrels were held in deep skepticism by American shotgunners. Beautiful, yes, but hang that thing over the fireplace quick. Never, ever shoot it. Why not? No matter how carefully crafted, critics maintained, the steel had microscopic flaws that weakened after repeated exposure to corrosive powder residue. The barrels would eventually blow out halfway up the forend, likely taking several fingers in the process.

But exhaustive testing by a small but dedicated cadre of traditional shotgunners has recently laid that myth to rest. A Damascus-barrel gun in good shape is still safe to fire with ammunition for which it was intended.

In the mid-1990s a company in the heart of Sweden’s “Iron Kingdom,” where Swedes have smelted since Viking times, developed a new process, arguably the first improvement in Damascus technology in 900 years. Steel droplets are atomized in inert gas, then dropped like molten lead from a shot tower. Resulting perfect spheres, just like pheasant shot, are collected, packed in a capsule, subjected to extreme heat and pressure in another inert gas environment and finally hand-hammered into whatever rough shape the customer desires. It’s three times stronger than traditional Damascus, the makers claim, and lest you think the Swedes are trying to slip us some snake oil, let it be noted this “Damasteel” was the material of choice for a Purdey 200th anniversary gun released this year.

If you love traditional shotguns, James Purdey and Sons needs scant introduction, other than Purdey was the gun of choice for kings, lords, dukes, earls, maharajas, emirs, sultans, various colonels in the Her Majesty’s Foreign Service and even a very ordinary one will cost you a home-equity loan.

Purdey celebrates its bicentenary in 2014 with three commemorative guns, each representing an historic production run. The aforementioned in Damasteel is an over-and-under 20-bore after the Woodward pattern, joined by a 12-bore side-by-side sidelock ejector game gun and lastly by a double rifle in .470 Nitro Express. Though no price is mentioned, the guns are available for viewing in The Long Room at their London address. By appointment only, of course.

Steve Culver of Meridian, Kansas, enjoyed a Huck Finn childhood, hunting and fishing while growing up on a farm. “Lumber, steel and machine parts were everywhere,” he remembers. “My parents tried to control my creativity by limiting the materials and tools that I had access to, but they were not entirely successful. Many of my creations included projectiles, explosives or excessive speed on some flimsy device, much to the horror of my parents and grandparents.”

Steve Culver of Meridian, Kansas, enjoyed a Huck Finn childhood, hunting and fishing while growing up on a farm. “Lumber, steel and machine parts were everywhere,” he remembers. “My parents tried to control my creativity by limiting the materials and tools that I had access to, but they were not entirely successful. Many of my creations included projectiles, explosives or excessive speed on some flimsy device, much to the horror of my parents and grandparents.”

“The child is father to the man,” the poet said, and nowhere is it truer than in Steve Culver’s life. Forced by necessity to spend 25 years working in a dog food plant, Culver never forgot his childhood. In his spare time, he studied and was awarded Master Gunsmith status. He made his first knife in 1987, sold his first blade two years later. He passed the American Bladesmith Society’s Master exam in 2007. Want a Culver blade with 10,000-year-old mammoth ivory grips? He does not take orders but will allow you to stand in line to purchase whatever he decides to build next.

When Culver realized he could not build both knives and guns, he forsook gunsmithing, almost. In September 2012 he forged and test-fired his first Damascus barrel, the first American to do so in at least a century.

The tube was for “a Cut-N-Shoot,” an edged weapon attached to a flintlock pistol, a period-perfect French replica from the late 1700s that Culver dubbed “Laffite’s Revenge,” a weapon to assassinate President James Madison. What? Culver tells a great story.

In the early 19th century Jean Laffite ran an immense privateering and smuggling operation in the New Orleans area, selling goods stolen on the high seas in his brother’s blacksmith shop in the French Quarter. In 1812 the U.S. government raided Laffite’s headquarters, arrested his men, seized ships and cannon. On the eve of the Battle of New Orleans, Laffite proposed a deal. He would help defend the city from the British in exchange for clemency. After the victory, President Madison granted Laffite and his men a full pardon. However, Laffite’s property was not returned. Lafitte became very bitter and contemplated revenge. His heritage and profession suggests that he might have been pleased to have in hand such a combination weapon.

The barrel, the lock, hammer, frizzen and stock fittings of Culver’s Cut-N-Shoot are all Damascus, and the piece is fully functional. Asking price? Thirty-eight grand and small change.

The ancient Mayan stone calendars ran out in 2012 and nobody knew if the Mayans pegged the end of the world or just got tired of carving. Didn’t matter, a minor hysteria and media frenzy erupted. Then there are the Biblical Revelations of St. John, which visualize four horsemen, bringing war, disease, famine and death, spooky stuff.

The ancient Mayan stone calendars ran out in 2012 and nobody knew if the Mayans pegged the end of the world or just got tired of carving. Didn’t matter, a minor hysteria and media frenzy erupted. Then there are the Biblical Revelations of St. John, which visualize four horsemen, bringing war, disease, famine and death, spooky stuff.

J.R. Cook of Nashville, Arkansas, commemorated the event, or non-event, with his End of Time series of Damascus blades. Cook, after a career as an industrial millwright, took to forging knives in 1986 after a grant from the Arkansas Art Council funded 400 hours of instruction under a master bladesmith. Classes in silversmithing and engraving followed.

Of particular interest is the etching exhibited on the End of Time series, wherein he drew images with a stylus on an acid-resistant asphalt. Sadly, the series was broken up.

“One man could not afford the whole thing,” Cook laughs. “The pieces started at nearly a grand and went up to ten times that.” Perhaps one day, barring the End of the World, a single collector can put all the pieces back together like they belong.

Cook is acutely interested in the original Bowie knife built for the hero of the Alamo about 1830 in Old Washington, Arkansas, not 30 miles from his home.

“There is considerable controversy about the materials used,” he muses. “The original ‘Arkansas Toothpick’ may have been forged from a meteorite, nobody really knows.

But we do know the smith was a man named James Black and three examples of his work survive. One was in possession of a dying Mexican farmer who gave it to a Texas Ranger to settle a debt. The second is marked “Bowie #1” and the third, which is unmarked, was also made in the classic Bowie pattern. All are in museums today. Obviously, the Mexican knife was the likely blade Bowie carried at the Alamo.”

Many credit James Black with rediscovering the Damascusblade. But was the original Bowie knife Damascus steel? Supposedly forged from a meteorite, it certainly met the criteria, tough and pliant, “long enough to use as a sword, sharp enough to be used as a razor, wide enough to be used as a paddle, and heavy enough to be used as a hatchet,” according to one historian. And Black was so secretive about his technique that he hung a leather curtain across his smithy door when he was at the forge. On his deathbed, he tried to share his secret with a friend, but alas, he could no longer remember and he took his recipe to the grave.

But has J. R. Cook ever tried to make a knife from a meteorite? “Yes, but you never know what you will end up with, and the stuff costs around $150 an ounce. Ideally, you will get iron with a trace of nickel burned clean by friction of the air, but if the meteorite hit the ground hot, it would have picked up dirt and rock. You can work hours and hours just to have the thing crumble when you are done.”

But has J. R. Cook ever tried to make a knife from a meteorite? “Yes, but you never know what you will end up with, and the stuff costs around $150 an ounce. Ideally, you will get iron with a trace of nickel burned clean by friction of the air, but if the meteorite hit the ground hot, it would have picked up dirt and rock. You can work hours and hours just to have the thing crumble when you are done.”

When J. R. Cook got that grant to study under a master bladesmith, he studied under Jerry Fisk. Fisk began making knives in 1974 and became a journeyman smith through the American Bladesmith Society in 1987. Two years later he became the 17th Master Smith recognized by the Society. Fisk has received Beretta’s Outstanding Award for Achievement in Handcrafted Cutlery, the Bill Moran Award for the American Bladesmith Society’s 1990 Knife of the Year, the Arkansas Governor’s Award and currently holds the title of National Living Treasure, the first knifemaker to receive this title.

“And through it all,” he laughs, “I wore clean underwear like my momma taught me to.”

Fisk remains proud of his humble beginnings. “I was one of five boys in the family. When it rained, the roof leaked. When it was time for a bath, I toted buckets of water into the kitchen for the tub. Until I was ten years old I thought my name was “boy, go get water.”

Fisk’s daddy was a preacher, called by the Lord to help folks in need. When a blacksmith hit town down on his luck, Poppa helped him set up his shop.

“The man built a board table and sold his knives by the side of the road.”

If that itinerant smith got Fisk’s attention, a school field trip to James Black’s shop in Old Washington captured it forever.

Old Washington was founded in the 1820s and soon became a major stopping spot on the Southwest Trail, a pioneer trade route from St. Louis to the Mexican border. It was a rendezvous for Jim Bowie, Davy Crockett and Sam Houston on their way to Texas. Later, Old Washington, then simply Washington, served as the Confederate capitol of Arkansas. The business district was ravaged by two fires in the late 1800s and all but abandoned by 1900. In 1958 the Pioneer Washington Restoration Foundation set to preserving remaining buildings and recreating those that were lost. James Black’s log smithy with charcoal forge and hand-operated bellows dates from that effort and has since become a shrine for traditional knifemakers.

“There are 126 mastersmiths worldwide and roughly half were once students of mine,” Fisk says. “I’d says that fully 99 percent of them work with Damascus steel, either full time or occasionally, but there ain’t nothing glamorous about getting your shirt burnt off. The forge is around 3,000 degrees, and in the summertime it’s like standing before hell with the doors open.

“You see photos of all the smiths with their long beards? That ain’t for looks, it’s to keep your face from getting broiled. Skin cancer is an occupational hazard. Back when I started, nobody realized that. Today, all my students wear face shields.”

Fisk takes orders from customers worldwide and is now about eight years behind.

“When things slow down in the U.S., I can always tell where the economy is booming. I get orders from as far away as Brazil and China.”

Fisk’s next project is far-and-away his most ambitious yet, a Damascus blade with a layer for every man, woman and child in America – 346 million. Into the blade he will forge tiny bits of steel from the Golden Gate Bridge, the Statue of Liberty, spaceships, from every war, the Revolution to Afghanistan, including a Yankee cannon ball fired on April 15th, 1864.

Now, that’s our history, alive and well, forever preserved by an artisan blacksmith.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 2014 May/June issue of Sporting Classics. The photographs of Napoleon’s Percussion Sporting Gun were provided by Robert M. Lee and Yellowstone Press. They originally appeared in Art of the Gun, a five-volume series of miniature books showcasing highly decorated firearms from the Renaissance to the 21st century. Measuring 4¾ x 6 inches and averaging 75 pages, each book features spectacular photographs and dramatic fold-outs. The set retails for $115.

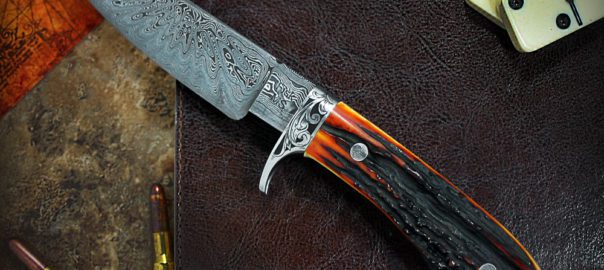

Handle: Stag Blade Length: 4.00″ Overall Knife Length: 9.250″

Handle: Stag Blade Length: 4.00″ Overall Knife Length: 9.250″

Just one look tells you this knife is focused on function but doesn’t skimp on style. Talk about love at first sight! The stainless steel bolster and generously sized handle furnish control and safety, the blade design provides you with unerring service. Blade length of 4-inches. Buy Now