It wasn’t all that long ago that fire was considered the nemesis of wild lands and wildlife. As a kid growing up in the 1960s, I can remember quite clearly hearing Smokey the Bear’s stern warning about forest fire prevention. Smokey was right for the most part, but he didn’t tell us the whole story.

Wildfires can be terribly destructive, of course, but controlled burns, managed by wildlife professionals, are a different matter. In recent decades wildlife managers have come to recognize the value of fire, and in some cases the absolute need for it.

Today controlled, or “prescribed,” fires are regularly used as a tool to improve wildlife habitat for game and non-game species alike. These burns can discourage invasive species, restore historic landscapes, remove the accumulation of combustible fuel, reduce predator numbers, and increase productivity for wild things of all kinds.

Case in point: On my home turf, in Saint Croix County, Wisconsin, 100 years ago, much of the original tall-grass prairie habitat was converted to agriculture. As those farms came and went, some of that land went feral and was covered in non-native vegetation. In other areas, trees were planted in single-species groves to control erosion. None of that land was terribly productive wildlife habitat.

In the last few decades, some of that land has been reacquired by the state and federal governments and been converted to State Wildlife Management areas and Federal Waterfowl Production Areas. It’s there that managers are restoring the original prairie habitat with periodic burns.

There are several advantages to using fire rather than other options, like herbicides or plows, to restore the landscape. When a prescribed fire is used before excessive debris has built up, a low-intensity burn results. This effectively removes accumulated debris and exposes the soil just enough for native species like big bluestem, buffalo grass, and a wide variety of wildflowers to germinate.

Today’s land managers aren’t the first to use this knowledge, either. There is ample evidence that before European settlers arrived, Native Americans also set fires to spur new vegetation, and thus bring in more game.

The benefits are seen very quickly following the prescribed fire, as new green growth carpets these recent burns within a few weeks. That new growth brings the critters back, too. Beyond the obvious beneficiaries—pheasants, ducks, deer, and other game species—countless, less-obvious organisms thrive on the newly fired landscape. Reptiles, songbirds, insects, even aquatic species present in adjacent wetlands all benefit from these periodic burns.

According to Pheasants Forever biologist Matt Christensen, early season burns like the ones being conducted now “do an excellent job of knocking back cool-season invasives like smooth bromegrass. This allows warm-weather native grasses like bluestem, which emerge later, to grow without competing with the non-native grasses.”

A prescribed burn at Oak Ridge Waterfowl Production Area in western Wisconsin. (Photo: Crowley Images)

Christensen also stressed that while prescribed burns sometimes remove individual nesting covers for a season, “the resultant improvement in habitat dramatically increases nesting success for the next four to five years for a wide variety of ground-nesting birds, including pheasants, turkeys, and other species.”

Wisconsin DNR wildlife biologist Ryan Heffele agrees that the burns are necessary to spur the growth not only of warm-season grasses like bluestem, Indiangrass, and switchgrass, but also for the later germination of flowering native forbs like coneflowers and blazing star. Those flowering plants add to the habitat variety, but just as importantly, they attract insect life and provide seeds crucial to brood survival.

“Young birds in particular,” Heffele said, ”depend on insects and seeds for much of their diet.”

An added benefit of the grassland fires is the removal of woody vegetation which often harbors large numbers of avian and mammalian predators, according to Heffele.

All in all, prescribed fires have become one of the most important tools in the wildlife manager’s arsenal for maintaining high-quality, high-value wildlife habitat. Now if we can only re-educate the public on this important truth . . .

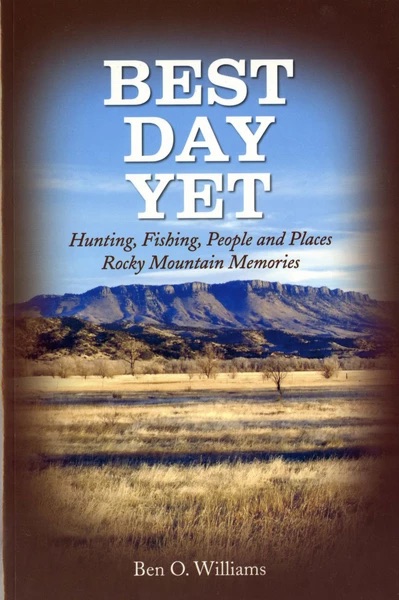

This book is a collection of the author’s true-shared essays of outdoor activities and of the folks he has encountered on the Great High Plains. It’s Ben’s Rocky Mountain Memories of hunting, fishing, people and places. This book has a far wider appeal than just for the hunting and fishing audience. No matter where you live, or what age, or in what walk of life you live, one of these essays will revive your memory of an experience in some way you had or someone in your family has handed down to you.

This book is a collection of the author’s true-shared essays of outdoor activities and of the folks he has encountered on the Great High Plains. It’s Ben’s Rocky Mountain Memories of hunting, fishing, people and places. This book has a far wider appeal than just for the hunting and fishing audience. No matter where you live, or what age, or in what walk of life you live, one of these essays will revive your memory of an experience in some way you had or someone in your family has handed down to you.

The stories are all vintage Ben; his writing is honest, heartfelt, always intends to be instructive, and is simply fun to read. They are not about killing things or hook and bullet stuff. These essays are about appreciating the land, enjoying the chase with his bird dogs, fly-fishing, conversations with outdoor folks and kicking gravel with landowners. Then, after each one of Ben’s stories there is a vignette, written by one of his many outdoor friends. Best Day Yet is an attitude that Ben created for himself. It’s how he feels about things according to his sense of the world around him. It’s like sitting by a mountain lake after a wonderful day of fishing with a flask of cheap blended scotch whiskey and believing an airplane dropped a fine 30-year-old single malt scotch whiskey that just drifted to shore at the exact spot where he was camping. His partner sitting next to him says, “What do you think of the whiskey?” “That’s one fine scotch.” Buy Now