“It was the Depression, and the wealthy had money to spend on their boats and outdoor recreation, even in the worst of times,” he would reflect. “And the tips were good.”

At 18, he was awarded Ordinary Seaman certification from the U.S. Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation. Adolph became the youngest licensed pilot on the Great Lakes at that time.

At 19, Uncle Sam shipped him to Europe where he served in two theaters during World War II. Four years later, on the return trip home from Italy, he dreamed of the calmer waters of the Great Lakes, his new bride and weekends spent with relatives near Little Bay de Noc in Escanaba.

With the war over, he found work away from the harbor. Using a Veteran’s Loan, he had a brick home built in the northwest suburb of Mount Prospect. He also saved enough money to buy a small used boat.

I recall weekends and vacations revolving around Father’s boats. A 30-mile drive north to a chain of lakes near the Wisconsin border became one of our favorite destinations. It was on Fox Lake that Father taught me the finer points of fishing. Perch were our favorite; bass came in second.

“Your grandmother and I fished off the piers at the harbor for perch when I was your age,” Father recalled. “We’d walk down to the Lake and catch a pail full for supper during the Depression. On the way home, we’d collect coal tossed off the trains by the engineers, who knew it would be used to fuel stoves for cooking and heating.”

Weeklong family vacations were spent up north in Wisconsin’s Vilas County, camping on the shores of Big Muskellunge Lake. Father would rent a wooden rowboat, and we’d fish for panfish, bass and maybe, just maybe, a muskie. Several times during the week our family drove to nearby Sayner to look at big muskies on display in glass-covered storefront freezers. After dark, we’d watch scavenging black bears at the local dump.

In 1967, my father’s company transferred him to Wisconsin, a move that proved to be the best thing that could have happened to me. We moved to the land of woods and waters, and at 13, I was in outdoor heaven. Father brought along his boat and rented a cabin on a lake while our new home was being built near Milwaukee. We spent evenings and weekends fishing and boating with Father and his friends. In time, the waters of Green Bay and Lake Michigan beckoned, and Father heeded the call. Offshore from the Door County Peninsula, we’d catch stringers of smallmouth bass.

When Father retired in 1985 and moved north to Wausau, my mother convinced him to buy a larger, albeit used, boat. A dreamboat he had longed for. I remember Father at the helm, grinning from ear to ear with pride and satisfaction. Today, a picture of the boat hangs in my office next to his framed 1938 seaman’s pilot’s license.

Father and Mother had one final wish: to be cremated and have their ashes spread along the shore of Big Muskellunge Lake. Mother is now 96 years old. When the time comes, she’ll join her beloved husband Adolph by the lake. Their two grown grandsons and I plan a small ceremony – including a day fishing from a rowboat for bream, bass and maybe, just maybe, a muskie.

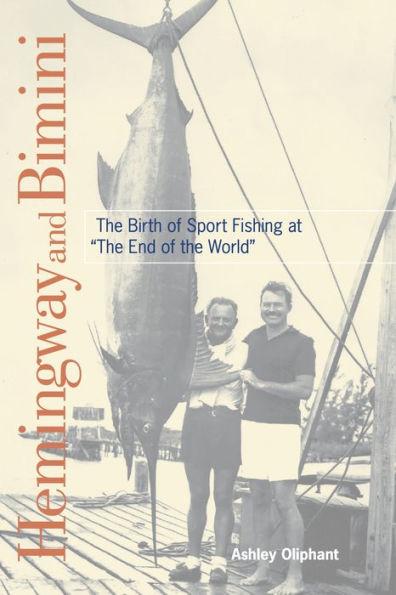

Follow Ernest Hemingway’s exploits on the Bahamian island of Bimini from 1935 to 1937, the very moment in time when the International Game Fish Association (under the author’s co-leadership) was emerging. Covers Hemingway’s role in the formation of the IGFA, his under-appreciated seminal writing about competitive saltwater angling when the sport was still in its infancy, the amazing fishing he enjoyed on the island, and the way all of these experiences translated into the composition of his posthumous novel Islands in the Stream.

Follow Ernest Hemingway’s exploits on the Bahamian island of Bimini from 1935 to 1937, the very moment in time when the International Game Fish Association (under the author’s co-leadership) was emerging. Covers Hemingway’s role in the formation of the IGFA, his under-appreciated seminal writing about competitive saltwater angling when the sport was still in its infancy, the amazing fishing he enjoyed on the island, and the way all of these experiences translated into the composition of his posthumous novel Islands in the Stream.

This is the only book on this period in Hemingway’s life and reveals unexpected dimensions to the Hemingway portrait that deserve attention, including his surprising humor, his advanced conservationist views several decades before the environmental movement even began, and his egalitarian ideas about his contemporary female counterparts in the big-game fishing world—challenging the usual portrait of Hemingway as a chauvinist with no personal rules, boundaries, or conscience. Includes beautiful vintage photographs of 1930s Bimini that have never been published in book form. Shop Now