Early next morning we were over at the elk carcass, and, as we expected, found that the bear had eaten his fill at it during the night.

His tracks showed him to be an immense fellow and were so fresh that we doubted if he had left long before we arrived; we made up our minds to follow him up and try to find his lair.

The bears that lived on these mountains had evidently been little disturbed; indeed, the Indians and most of the white hunters are rather chary of meddling with “Old Ephraim,” as the mountain men style the grizzly, unless they get him at a disadvantage, for the sport is fraught with some danger and but small profit. The bears thus seemed to have very little fear of harm, and we thought it likely that the bed of the one who had fed on the elk would not be far away.

My companion was a skillful tracker, and we took up the trail at once. For some distance it led over the soft, yielding carpet of moss and pine needles. The footprints were quite easily made out, although we could follow them but slowly; for we had, of course, to keep a sharp lookout ahead and around us as we walked noiselessly on in the somber half-light always prevailing under the great pine trees, through whose thickly interlacing branches stray but few beams of light no matter how bright the sun may be outside.

We made no sound ourselves, and every little sudden noise sent a thrill through me as I peered about with each sense on the alert. Two or three of the ravens that we had scared from the carcass flew overhead, croaking hoarsely, and the pine tops moaned and sighed in the slight breeze—for pine trees seem to be ever in motion, no matter how light the wind.

After going a few hundred yards, the tracks turned off on a well-beaten path made by the elk; the woods were in many places cut up by these game trails, which had often become as distinct as ordinary footpaths. The beast’s footprints were perfectly plain in the dust, and he had lumbered along up the path until near the middle of the hillside, where the ground broke away and there were hollows and boulders. Here there had been a windfall, and the dead trees lay among the living, piled across one another in all directions, while between and around them sprouted up a thick growth of young spruces and other evergreens. The trail turned off into the tangled thicket, within which it was almost certain we would find our quarry.

We could still follow the tracks by the slight scrapes of the claws on the bark or by the bent and broken twigs, and we advanced with noiseless caution, slowly climbing over the dead tree trunks and upturned stumps and not letting a branch rustle or catch on our clothes. When in the middle of the thicket we crossed what was almost a breastwork of fallen logs, and Merrifield, who was leading, passed by the upright stem of a great pine. As soon as he was by it he sank suddenly on one knee, turning half round, his face fairly aflame with excitement.

As I strode past him, with my rifle at the ready, there, not ten steps off, was the great bear, slowly rising from his bed among the young spruces. He had heard us but apparently hardly knew exactly where or what we were, for he reared up on his haunches sideways to us. Then he saw us and dropped down again on all fours, the shaggy hair on his neck and shoulders seeming to bristle as he turned toward us.

As he sank down on his forefeet I had raised the rifle; his head was bent slightly down, and when I saw the top of the white bead fairly between his small, glittering, evil eyes, I pulled the trigger. Half-rising up, the huge beast fell over on his side in the death throes, the ball having gone into his brain, striking as fairly between the eyes as if the distance had been measured by a carpenter’s rule.

The whole thing was over in 20 seconds from the time I caught sight of the game; indeed, it was over so quickly that the grizzly did not have time to show fight at all or come a step toward us. It was the first I had ever seen, and I felt not a little proud as I stood over the great brindled bulk, which lay stretched out at length in the cool shade of the evergreens. He was a monstrous fellow, much larger than any I have seen since, whether alive or brought in dead by the hunters.

As near as we could estimate (for, of course, we had nothing with which to weigh more than very small portions), he must have weighed about 1,200 pounds, and though this is not as large as some of his kind are said to grow in California, it is yet a very unusual size for a bear. He was a good deal heavier than any of our horses, and it was with the greatest difficulty that we were able to skin him. He must have been very old, his teeth and claws being all worn down and blunted, but nevertheless he had been living in plenty, for he was as fat as a prize hog, the layers on his back being a finger’s length in thickness. He was still in the summer coat, his hair being short, and in color a curious brindled brown, somewhat like that of certain bulldogs. All the bears we shot afterward had the long, thick winter fur, cinnamon or yellowish brown.

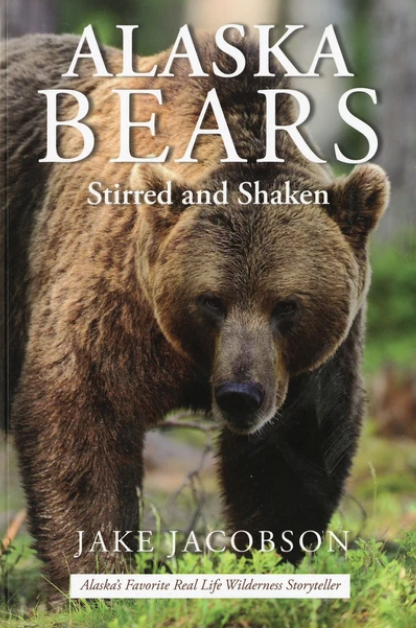

Alaska Bears: Stirred and Shaken is a collection of 24 stories describing Jake’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska. Buy Now

Alaska Bears: Stirred and Shaken is a collection of 24 stories describing Jake’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska. Buy Now