It is not a thing life prepares one for, no matter how much meat has been secured in this fashion following a successful elk or deer hunt.

The name fits. Clyde. I picture a “Clyde” and see leathery features beneath a black, grease-crusted Stetson, floppy leather chaps polished by hard use, sterling-silver rodeo belt buckle too far worn to discern what was won by it, slope-heeled boots adorned by perpetual spurs loose in the rawls — the prerequisite Pancho Villa mustache. Add ill-fitting dentures, piercing black Irish eyes, an ever-present cigarette hung from the comer of his mouth, a slight frameset unsteadily on deeply bowed legs, and you have Clyde, my Utah mountain lion guide.

I don’t know what to make of this Clyde, nor do I venture to guess an age. There’s about a 30-year gap he might fit into, according to erosion or lack thereof.

He’s a true curmudgeon, constantly cursing even the smallest difficulties – prone to direct an undignified kick at the door of his new diesel4x4 because it fails to shut itself when he slides out to lay down tire chains for installation and it temporarily blocks his way. Moving in crab-like gestures, he’s ungainly afoot, but when he swings into the saddle atop his long-legged mule he’s poetry in motion.

As we ride he cusses relentlessly at a profusion of spotted, tongue-lolling hounds, each owning a decidedly Mexican moniker. I can never quite determine what these jolly canines are doing to illicit these colorful outbursts, but when we pause to take our saddle bag lunch beneath a sheltering bluff, he’s as gentle with them as newborns.

Towards me, he has very little to relate. I simply follow suit in whatever he does. I don’t take it personally. Clyde is certainly not without humor, but obviously scorns the human race and in some ways I can relate.

Clyde comes highly recommended via a clique of well-traveled acquaintances, cheery fellows who huddle on the fringes of cocktail parties to crow over who has squandered the highest sum of free-flowing Texas oil money pursuing some form of vaguely familiar fauna in a country with a name right out of a long-forgotten fairy tale. Clyde is described as a character, a good’ 01 boy who runs a pack of hounds that’ll eat the hind-end out of a grizzly bear. This is somehow reassuring.

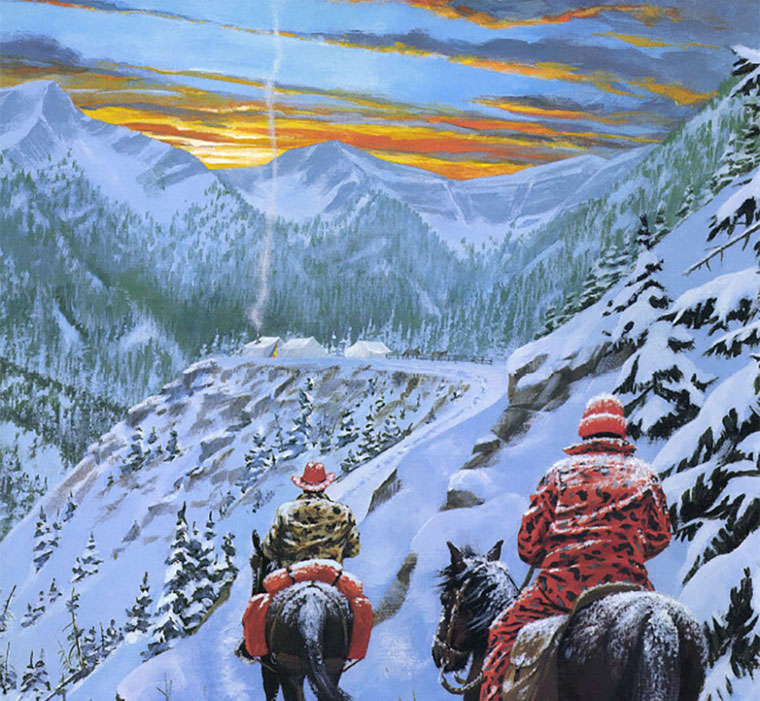

Clyde can persuade the stock-trailer-burdened truck no farther, working the steering wheel gingerly to stay between the ditches as wheels spin ineffectively and tire chains clank and vociferously batter wheel-wells from all quarters. His artfully constructed strings of curses form another brand of poetry, combinations unique and powerful and warranting individual copyright. He skillfully backs the trailer a half-mile and into a tum-around, and we alight, flinging open the rusted iron-pipe trailer as dilapidated as Clyde’s Chevy is shiny and new. The swarm of hounds flows tail-wagging and yodeling merrily through calm mule legs to wallow and burrow gleefully, the saddled mules shuffling impatiently, tucking their hindquarters in anticipation of the sudden, invisible drop to earth. There’s no fanfare or battle-plan discussion; business conducted on a need-to-know basis only.

I fling my burden of cased take down recurve and PVC-protected arrows over the saddle horn and clamor onto my mule, which is eager to overtake his trotting partner. Clyde is making time, his vile lexis filling the crystalline emptiness, ricocheting to embrace distant, ragged hills ringed in sheer cliffs. This is how we travel, at an uninterrupted trot, gobbling ground greedily in search of saucer-sized depressions in an unbroken sea of deep, flocculent white.

I occupy my saddle enough hours that without a wristwatch it would prove difficult to provide an accurate time estimate, though certainly a measured distance is beyond me now. Each knee joint is an angry protest of numbing pain. We might be very near the truck, or many black hours away. I cannot say for sure.

A gnawing wind is slowly rising to move the powdery snow in delicate veils, its edges as sharp as freshly broken glass, seeking the seams of my considerable high-tech clothing so that the day has simply become something to be endured. My only solace comes by way of a sun perceivably slanting westward to signal that this day is not without closing.

Even Clyde has grown silent, his most recent warming blasphemy delivered hours ago, followed by determined silence broken only by whistling wind, creaking saddle leather and the occasional click of stone beneath determined mule hooves. But that general lethargy transforms into something quite the opposite in an instant, as one of those blessed, carefree hounds releases a barrage of joyful screams and yelps that cannot be mistaken for anything less than triumph.

Clyde pulls his mule up short and raises one hand like a cigar-store Indian, his way of asking me to behold this beautiful music. Additional howls join the preliminary alarm, choppy and tentative, everything tangible turned to sound and emanating from an isolated piece of ground until it transforms into something primal and urgent that bounces from the bulwarks of smooth Navajo sandstone. He tickles his mule into a ragged gallop, rounding a spit of anchored stone and vaulting into the circle of hounds with agility I would not have attributed him minutes before. The mule ground-stakes and Clyde wades into the fracas bent at the waist, shoving eager hounds aside and staring into the blank snow as if reading a fortune, legs spread in a way of protecting something fragile and precious. He turns as I slide off my mule and I see him smile around his smoke, knowing something wonderful is unfolding.

Clyde gestures with the clean line of his jaw. Between his boots there is the perfect, crisp imprint of a cat paw that I can just cover with my outstretched hand — the spoor of a mature tom cougar. Clyde releases a satisfied whistle.

“They’ll jump him right yonder. Yessir,” Clyde offers, using his chin again as reference. “Listen to it and you’ll see.”

The hounds’ cries are being quickly drowned by gathering wind, but Clyde makes no move, affixed, head-cocked and crooked-grinning, waiting to be proven correct.

I am restless, every instinct I possess prodding for action, but I watch Clyde and listen so intensely I can nearly see it in my mind. Then there is something able to penetrate even devolving wind. A change in pitch, an extra bit of something indescribable but wholly evident and very real, something to be touched and walked around.

Clyde’s grin widens by the slightest margin. He shoots an imaginary finger pistol toward the receding howls.

“Jumped ’em,” he offers, flicking his cigarette spinning and turning toward his mule.

My mule assumes new enthusiasm. He has played this game before and enjoys its drama. He plows ahead as unerringly as a ship on smooth seas. I slowly understand I am no longer at the helm in any real sense. He is not heeding instruction; he cuts comers to prove he is not following Clyde’s lead. He is following the howls of the hounds — which have gone mad — surveying terrain and formulating a direct route of his own devising.

Even so the cowboy appears ahead, looping reins around the lower branches of a cavern-like juniper, watching me arrive with impatient eyes as he cinches a large revolver to his waist.

I toss reins into outstretched hands and slip off with my cased goods, falling to my knees to tear into the works. I’ve discovered the perfect tool for the job — a Fred Bear Takedown Supreme with slip-in limbs that snap into place nearly instantly. I admire the lovingly polished rose — and zebra-wood and blush at the extravagance of such a work of cut carried into this austere landscape.

Clyde is laboring before me, working up the loose rock of a tight chute leading higher into the cliff: creating small slides behind his slick boots, seemingly troubled and suddenly impatient. I pause to catch my breath, the abrupt jump in altitude from a sea-level existence suddenly all too apparent. Clyde is shooting me hard looks, turning to peer upwards with palpable angst. We climb ever higher.

He somehow knows.

The hounds are screaming into a void of swirling snow at the edge of the world, swarming about broken rock and intent on an isolated plunge of open space. Clyde mutters, breathing raggedly, concern written on his face as plainly as printed words.

“Bayed out there,” he manages between gasps. His face is running sweat, but nothing coherent registers beyond the fact I am almost there. I have an arrow on the string and we creep to the falling ledge, finding the massive cat backed to the very edge of precipice, hounds in his face and blaring like foghorns through slobbering jowls.

“I only ask you don’t shoot a hound,” Clyde manages between labored gasps, in a near pleading voice. I am breathing through a gaping mouth, but only later does it occur to me Clyde’s breathing is coming with some difficulty.

I shimmy closer to the edge while measuring the drop carefully. The cat rushes the hounds, too swiftly to record accurately. Somehow they are quicker, dodging like seasoned prize-fighters, staying just out of reach while also reluctant to give ground. I yank the string to my cheek and turn it loose too quickly in my overwhelming excitement. The arrow arches into the rocks below the tom and a shower of carbon splinters touch the great cat’s belly. He explodes through hounds in a reckless rush to regain solid ground, Clyde’s pistol exploding in my ear, a puff of pulverized sandstone swirling well behind the fluid bounding off the cougar’s snaking tail.

Then I am running without restraint, sprinting over broken slab rock, drawn by the frenzied screams of crazed hounds, driven by adrenaline and primitive impulse. I run until I reach the hounds, seeing the cat perched in a tortured cedar at the head of a sudden cut dropping into wind-driven snow that spins from a dull, paling sky.

The lion is just out of reach above the hounds that are setting up a clamor that cancels all senses. I wade into the hounds to get a closer look at this great cat, which is regarding us as calmly as a general weighing his options. My elbows on bent knees, I labor to draw oxygen into famished lungs and clear a spinning head.

I wait until I sense Clyde will not come. I wait until it is impossible for him not to have come. A nauseating fear seeps into my being, slowly taking its grip. The cat stares serenely with yellow-green eyes, coldly unwavering, calculating. I cease to hear the hounds, waiting, alone.

I am vaguely aware of the hounds’ inexorable receding as I stare at a reclined Clyde, cold to touch, appearing merely to be catching his breath, eyes wide open but unseeing. I have seen dead men, mangled and unrecognizable following oil rig tragedies. This is something else entirely. I sit and watch him, the sun receding toward he horizon as surely as fire eventually exhausts itself: until I can no longer ignore the inevitable.

The man proves surprisingly light over my shoulder, like a fireman rescuing the victim of a house fire. I clamor and slip down the chute we have earlier ascended, bolstering my agility and strength through a resolve not to subject Clyde to the indignity of being dropped like a sack of vegetables. The cold wind is sweeping away our tracks from earlier, making it even more difficult to reach the flat where the mules wait.

I proceed on dead reckoning, soon relieved to find the animals parked as we left them, where I struggle to secure Clyde to his saddle atop a remarkably composed mule. It is not a thing life prepares one for, no matter how much meat has been secured in this fashion following a successful elk or deer hunt.

I can no longer hear hounds and worry of their fate as well…what will become of them. I have no more experience in this area than I do packing a quickly stiffening corpse.

There is no trail to follow, no evidence of our earlier passage. I ride alone on a general gut feeling, fighting my mule in the beginning, clutching a semblance of control over a world yawing utterly out of control. This is not conducted consciously, but yielded from infecting if carefully controlled terror.

I hold onto myself tightly to tamp this fear into a safe place, more alone than I have been in a lifetime spent without the comfort of human presence. Eventually it suggests itself to simply give the mule his head, looping reins over the saddle horn and hugging my assembled bow to my chest to conserve warmth.

The first hound shows sometime after midnight, shadowy against moonlit snow, self-consciously happy, as if apologizing to have been discovered slacking from his appointed task. I talk to him quietly, my voice somehow startling to hear. She (I sense this somehow, that undeniable feminine quality) falls in behind the mules and we continue on our uncertain way. A pair of slinking hounds appears some hours later, skittish and circling well out of striking distance of a threat only they perceive. I test my repertoire of those Mexican names I remember Clyde roaring and they duck heads uncertainly and circle to fall in with the seemingly aloof hound already trailing.

In time I am beyond shivers, nodding off at intervals, woken by dizzying head bobbing that induces sickening nausea. I shake myself awake, registering my place in the world, surrendering to my mule’s plodding, steady gait. I have a wide assortment of hounds at my heel, and believe they are accounted for, every one. And then I drift off again, my head filled with chaotic dreams that lead nowhere but somehow loop in dizzying fluency. I sense a complete and sudden lack of motion that requires a few minutes to register; opening my eyes to find truck and trailer squatted before us like an unexpected religious revelation.

There is some ugly business to follow — stumbling off my mule, nearly unable to stand — rifling Clyde’s pockets for keys, panic spreading over me in my inability to locate them following a thorough search; discovering them in the ignition, relief spreading like a wave; sitting Clyde, stiff as lumber, in the passenger seat for his last ride. I spy hay in the truck bed and drag the entire bale into the trailer head, hounds and mules alike loading anxiously; swinging the rust squealing gate closed behind them.

I hold my hands to heat pouring from the vents, power the radio, push seek. The dial spins through its range three times before I note an AM setting. Trying FM the cab suddenly fills with Patsy Kline, that absolute miracle of human voice riding the airwaves across a desolate Utah desert, and I sit and weep.

Peter Capstick has been hailed as the adventure-writing successor to Hemingway and Ruark. This long-awaited sequel to Death in the Silent Places (1981) brings to life four turn-of-the-century adventurers and the savage frontiers they braved. Buy Now

Peter Capstick has been hailed as the adventure-writing successor to Hemingway and Ruark. This long-awaited sequel to Death in the Silent Places (1981) brings to life four turn-of-the-century adventurers and the savage frontiers they braved. Buy Now