If any art is truly timeless, it is the still-life.

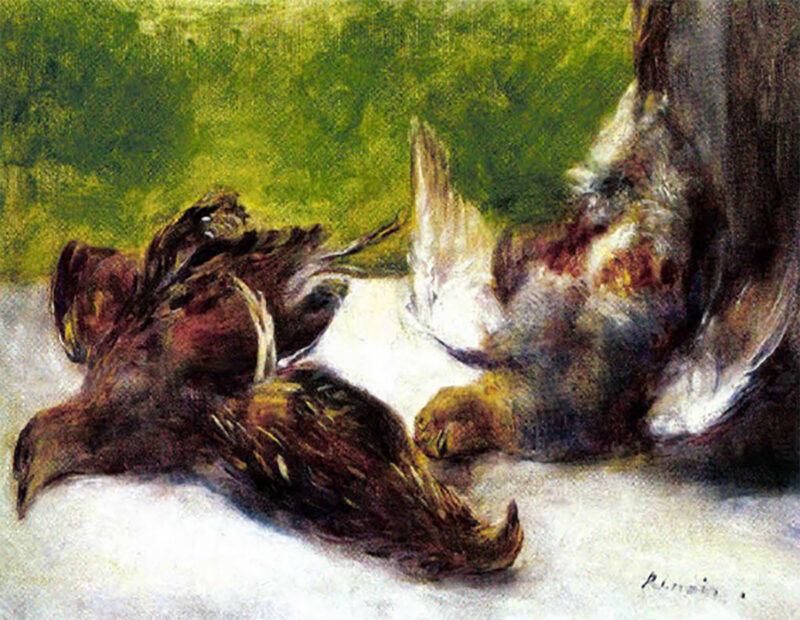

Trois Perdrix by French Impressionist Pierre-Auguste Renoir, c. 1880

The still-life does not depict a moment frozen in time, a chosen instant snatched from the temporal current, but a moment outside of time, beyond its erosive reach. There is no past or future, only an eternal present. And in the still-life with game, or “gamepiece,” painters of skill, vision and even genius have given us a body of work that, of all the branches of sporting art, makes the strongest claim as its crowning achievement.

An Italian artist named Jacopo de’ Barbari painted the first known gamepiece in 1504 — a gray (Hungarian) partridge hanging form a wall hook. Some 150 years would elapse, however, before the gamepiece achieved its apotheosis, and it would happen not in Italy, but in Holland and, to a lesser extent, Flanders (modern day Belgium). The flowering of pictorial art that occurred in the “Low Countries” in the 17th century ranks among the greatest achievements of Western civilization; there was the joyful, unabashed sensuality of Rubens, the penetrating intelligence of Rembrandt, the transcendent and all but inexplicable genius of Vermeer.

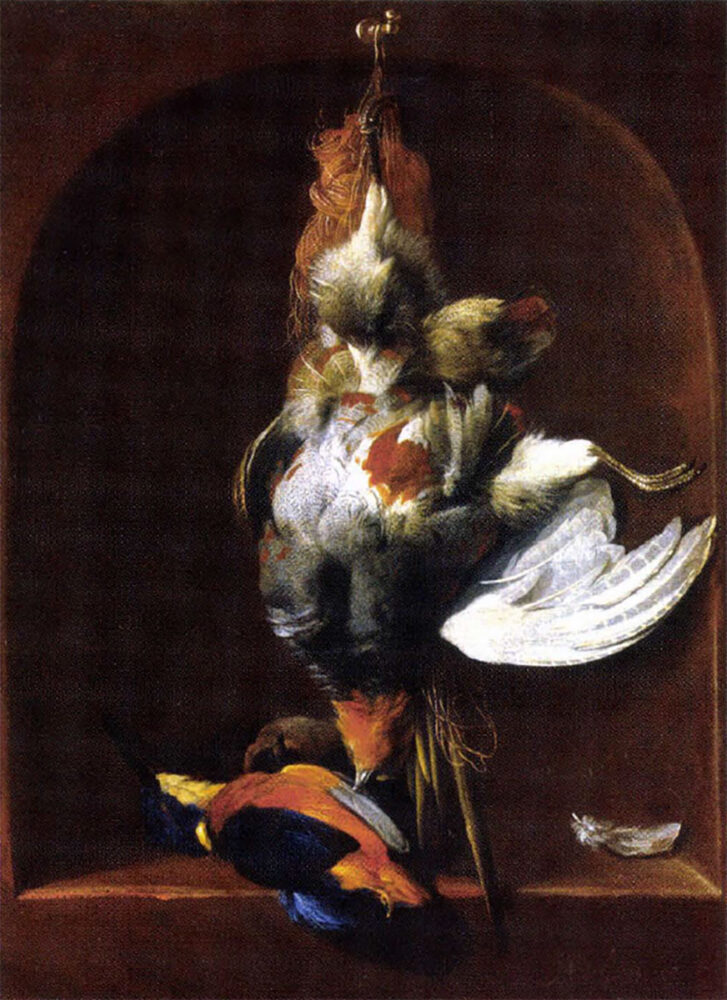

Still Life with Birds by Dutch artist Melchior

d’Hondecoeter, c. 1680

These and other artists of that time and place engineered nothing less than a revolution, shrugging off the dogmatic conventions that, since the fall of Rome, had dictated that only subjects drawn from history, religion or myth were worthy of treatment. The Dutch and Flemish masters of the 17th century celebrated the delights of the immediate, perceivable world, and they did so without relying on allegory and symbolism to raise their work to a “higher” plane. As E.H. Gombrich observed in The Story of Art, “They Simply represented a piece of the world as it appeared to them, and discovered that it could make just as satisfying a picture as any illustration of a heroic tale….”

The economics of art also underwent a sea change. Whereas under the traditional “patronage” system artists were typically employed by a single well-heeled benefactor — who, virtually without exception, would have been a member of the hereditary aristocracy — the 17th century witnessed the first art created and sold under “free market” principles. This was especially the case in Protestant Holland (as opposed to Catholic Flanders), where a burgeoning middle class of bankers and merchants — men of means, if not lofty pedigree — comprised an enthusiastic buying public.

In order to meet the demands of this clientele, the painters of Holland grew increasingly specialized — and one of the most popular areas of specialization was the still-life. A genre that had originated in classical Greece and flourished during the height of the Roman Empire, the still-life invoked no grand themes or profound metaphysical concerns. Instead, it invited the viewer to take pleasure in the sheer visual beauty of familiar objects — their colors, shapes and textures — and, by extension, to marvel at the artist’s skill in rendering and arranging them.

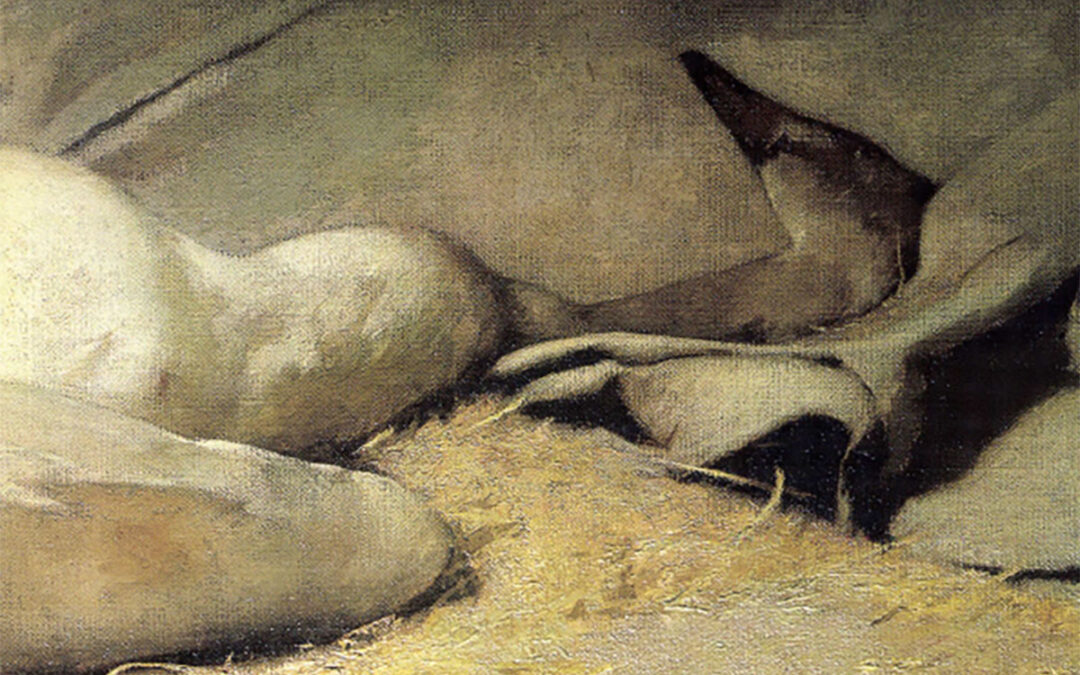

Still Life of Rabbits and Pheasant by Frenchman jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin, c. 1760

The early Dutch still-lifes were often “kitchen” or “market” scenes, paintings that depicted various foodstuffs. And because the Low Countries afforded excellent waterfowling and small game hunting — Valkenswaard, on the coast of Holland, was known throughout Europe as a mecca for falconry — the hares, partridges, pheasants, ducks, geese, swans and even songbirds bagged by Dutch and Flemish sportsmen inevitably found their way into these depictions, thus setting the stage for the bona fide gamepiece.

The artist who bridged the gap between the kitchen/market scene and the gamepiece was Frans Snyders, born in Antwerp circa 1579. But it was his student, Jan Fyt, who, in the 1640s and ’50s, took the final step. By entirely removing the gamepiece from the kitchen and adding dogs and other accoutrements of the hunt, he made the sporting connection utterly explicit. As Professor Scott Sullivan of North Texas State University puts it in his authoritative study The Dutch Gamepiece, Fyt’s goal was “the representation of the bountiful catch of the successful hunting party. This conception of the gamepiece, as a trophy of the hunt, increasingly prompted its execution in the second half of the 17th century.”

Still Life with Pheasants and Plovers by Claude Monet, c. 1880. In 1879, six of Monet’s thirty-five paintings that year were still-fifes of gamebirds. He was particularly fascinated by the iridescent coloring of pheasants.

While numerous Dutch artists, even Rembrandt, did gamepieces, three names stand out. The first is Jan Baptist Weenix, who is generally credited for bringing the genre to full maturity. Born in Amsterdam in 1621, he completed his first gamepiece, a scene of a hare and birds, in 1648. Weenix possessed astonishing technical virtuosity; in particular, he was a wizard at capturing the texture and “depth” of fur and feathers. This ability to persuasively portray three-dimensional objects on a two-dimensional surface led him to execute a number of trompe l’oeil (“trick the eye”) gamepieces, works that attempted to create the illusion that the actual bird or animal was hanging from the wall.

The most acclaimed practitioner of the trompe l’oeil gamepiece, however, was Weenix’s student (and nephew), Melchior d’Hondecoeter. Born in Utrecht in 1636, his work gained such fame that, during his lifetime, he became known as the “Raphael” of bird painting. He did numerous variations on the “hanging partridge” motif — viewing them, it is all you can do to convince yourself that, if you pressed your finger against the canvas, it wouldn’t sink into the bird’s pillowy feathers.

The last of the great triumvirate of Dutch gamepiece painters was Jan Weenix, the son of Jan Baptist Weenix, and, like his cousin d’Hondecoeter, a pupil in his father’s studio. Born in 1642, Jan Weenix was something of a throwback in that most of his painting was done on commission for a handful of wealthy patrons rather than created “on spec.” His leading patron was the German nobleman Johann Wilhelm; studying Weenix’s canvases at Wilhelm’s Bensburg Castle, the poet Goethe remarked: “To reanimate these inanimate creatures, this extraordinary man had marshaled his whole talent and in rendering the greatest variety of animal textures — bristles, hair, feathers, antlers, claws — he had equaled and, with regard to effect, surpassed nature.”

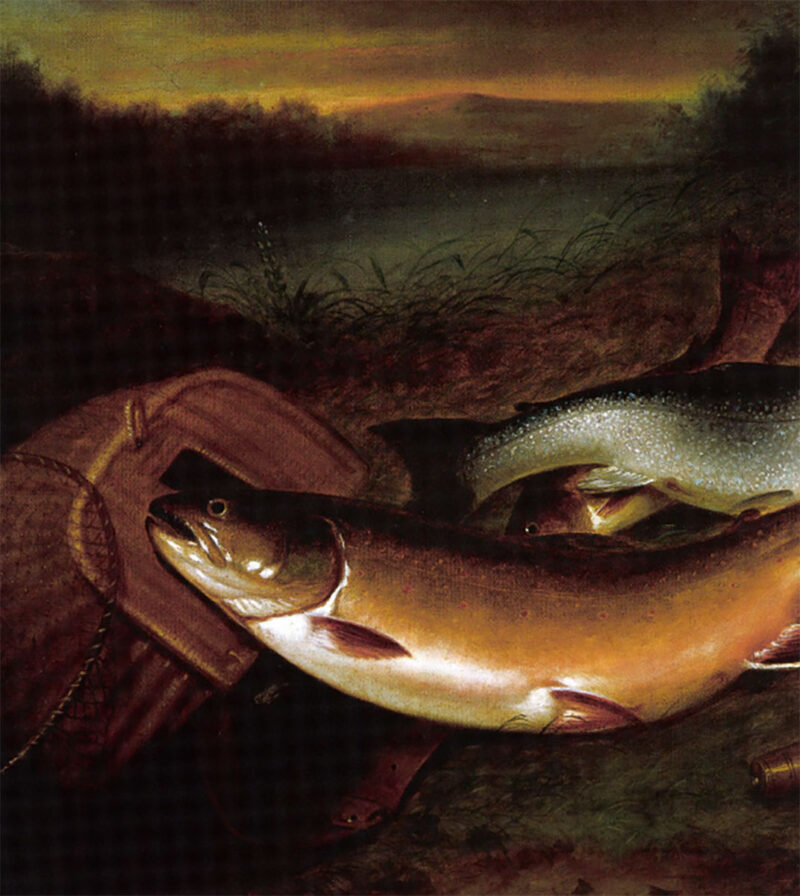

The Day’s Catch, c. 1862, an oil-on-canvas. Boston artist Walter M. Brackett was among a number of American and British painters who concentrated on still-lifes of trout and salmon in the mid- to late-19th century.

With the death of Jan Weenix in 1719, the heyday of the Dutch gamepiece came to a close. But while the genre as a whole would never again enjoy an era of such concentrated activity — or of such rich accomplishment — painters elsewhere in Europe were quick to follow the Dutch lead. Among the earliest to do so was Francis Barlow. Considered Britain’s first important sporting artist, Barlow completed a number of attractive gamepieces, the best-known of which is probably The Game Larder (1672). Although his compositions in this vein were perhaps not as sophisticated, especially in terms of design, as their Dutch and Flemish counterparts, Barlow’s works exude a certain mellow, typically English charm.

Across the Channel, the French artist Jean-Baptiste Oudry sounded a new note in the genre with such dramatic, highly stylized compositions as Return from the Hunt with a Dead Roe (ca. 1720s). A court painter to Louis XV, Oudry broke from the Dutch-Flemish tradition by rendering his birds and animals in a loose, interpretive fashion rather than in the tightly controlled, faithful-to-nature manner favored by his Low Country predecessors.

Oudry’s successor in the French “line,” Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin, took the gamepiece in yet another direction. There is a solemn, almost elegiac tone to Chardin’s painting, reflective not only of the subtlety of his rendering and quietly powerful sense of design, but of his restrained and nuanced use of color. His work showed that, despite the genre’s limitations, it was possible to suffuse the gamepiece with that elusive quality known as mood. It seems clear that Chardin intended his still-lifes of game to appeal primarily to connoisseurs of fine art, and only coincidentally to sportsmen.

Still Life with Red Fox and Mallard Drake, c. 1860, reflects the dramatic, exactingly realistic style of Belgian artist Eugene Joseph Verboeckhoven.

In the 1800s, a number of artists in Britain and mainland Europe tried their hand at gamepieces. Few, however — with the possible exception of Belgium’s Joseph Verboeckhoeven — seem to have made the genre their specialty. Sir Edwin Landseer, said to be Queen Victoria’s favorite painter, completed a handful — another 19th century Briton who did startlingly excellent work in this genre was the gifted (but obscure) Tom Hold. Several of the luminaries of the Impressionist movement, including Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet, also dabbled in gamepieces.

Then, in late-19th century America — where a new generation of sportsmen had swarmed to the woods, fields and marshes in the decades that followed the Civil War — a kind of gamepiece renaissance occurred. Leading the way was the Irish-born artist William Harnett, an advocate of the trompe l’oeil approach. Photography had of course become firmly established by then, but Harnett, despite his extraordinary attention to detail, was somehow able to elevate his work above what one critic called photography’s “commonplace realism.” As the artist himself declared, “I do not closely imitate nature. Many points I leave out and many I add.”

Another notable exponent of the trompe l’oeil style was Richard LaBarre Goodwin. A native of Albany, New York, Goodwin was known for his life-sized canvases of gamebirds — stunningly well-rendered ones — hanging from cabin doors. Indeed, his most famous work, painted circa 1905 for the Lewis and Clark Centennial in Portland, Oregon was entitled Theodore Roosevelt’s Hunting Cabin Door.

Richard LaBarre Goodwin was a notable exponent of trompe l’oeil, as seen in this 1880 painting, Hanging Game.

Harnett and Goodwin, while hugely popular, had no monopoly on the market. Alexander Pope also had an enthusiastic following as did Sidney I. Brackett, Walter M. Brackett (no relation to the former, although both were Bostonians) and William Machen. Typically, these artist of the American “school” presented the gamepiece as a kind of trophy, emblematic of the successful hunt and the skill of the sportsman.

In contrast, the work of Danish-born Soren Emil Carlsen, who was hailed as America’s leading still-life painter at the turn of the century, was more in the vein of Chardin: lyrical, powerful and sometimes — as in his Still-life with Swan (1894) — haunting. Like Chardin, too, Carlsen viewed birds as objects of intrinsic aesthetic interest; if anything, though, he went beyond Chardin in exploring the design possibilities inherent in the birds’ shapes, colors and tonal values.

Another trend that surfaced in the mid- to late-19th century was the increasing popularity of gamefish — trout and salmon in particular — as subjects for sporting still-lifes. Leading the way were the Briton William Geddes and Samuel Kilbourne of Maine — A.F. Tait, who relocated from England to New York in 1850 and is considered America’s first important sporting artist, also did a few paintings in this vein. These canvases often include tackle such as rods, reels, creels, etc., and they raise the interesting question of whether a still-life with fish in it — but without anything wearing feathers or fur (except flies, perhaps) — can properly be termed a “game”-piece.

Renowned still-life artist Thomas Aquinas Daly shares his fascination with the “beautiful array of curves, shapes and textures from every angle” in the Head of an Eight-Point Buck (detail).

Although the gamepiece never entirely disappeared from the American scene, it became relatively uncommon following Carlsen’s death in 1932. Artists continued to do them, certainly. For a brief but intense period in the mid-1960s, Jack Cowan painted a number of gamepieces — all of which display his characteristic panache. But he abandoned the genre almost as quickly as he’d taken it up. Laughs the 81-year-old Cowan, “It was a phase, I guess.”

It was not until the emergence of Thomas Aquinas Daly in the late-1970s/early ’80s that the gamepiece once again had a significant presence in American Sporting art. Encouraged by his friend and mentor Bruce Kurland — and inspired not only by Chardin and the 17th century Dutch and Flemish artists but by the likes of Whistler, Homer, O’Keefe and the mysterious Albert Pinkham Hyder — Daly’s brooding, austerely poetic work has a deep, elemental appeal.

For Daly, the desire to do a gamepiece begins with the birds themselves. “I remember the incredible feeling I had as a kid when I’d shoot, say, a pheasant,” he recalls. “I was so excited just to hold it in my hands that I could barely breathe; it was such a beautiful thing. That sense of the bird as a beautiful object is a big part of the attraction that these pieces have for me.”

Ken Carlson’s Still Life with Hanging Canvasback shows his love for strong design and eye-catching contrast between light and shadow.

Daly also cites the “tremendous freedom” that still-lifes afford in terms of design. “Because you’re not depicting a scene from nature,” he observes, “you can arrange the elements any way you want to. Composition is something I really dwell on, along with the drawing. I want the viewer to be ‘hooked’ with just one look — although as someone who’s very critical of his own work, I’m not often satisfied that I’ve pulled it off.”

In contrast to Daly’s darkly moody work, Ken Carlson’s still-lifes with game have a formal elegance — if John Singer Sargent had painted gamepieces, this is what they would have looked like.

“They’re a nice break from my usual wildlife-in-landscape paintings,” says Carlson, “and they’re a lot of fun to do. But they’re not easy. I spend a lot of time playing around with the settings, moving the wings this way and that, seeing how they catch the light. In particular, I love the contrast between light and shadow, and the abstract forms they create.”

Redhead Still Life by John P. Cowan.

Adds Carlson, “The design is the part of these paintings that really appeals to me — but the rendering’s important, too. I have a network of ‘collectors’ who send me birds, and I’m always amazed at how beautiful they are, even in death. My style is not trompe l’oeil, obviously, but that beauty is something I try very hard to convey.”

Beauty: Throughout the history of the gamepiece, this — “Ever ancient and ever new,” in the words of St. Augustine — has been at the heart of the artist’s quest. And in the birds, beasts and fishes that stir the sportsman’s heart, these twinned desires merge to speak in a single, deeply resonant voice.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 2002 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

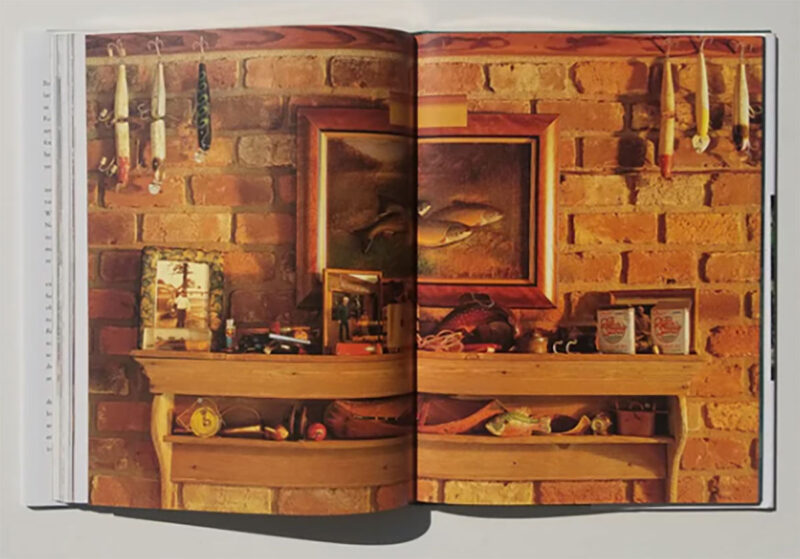

This book celebrates the landscapes, histories and habitats that have served as the famed North Carolina artist’s inspiration. For more than twenty-five years, Timberlake’s artistic efforts have been internationally acclaimed for their fine depictions of the region’s life and heritage.

This book celebrates the landscapes, histories and habitats that have served as the famed North Carolina artist’s inspiration. For more than twenty-five years, Timberlake’s artistic efforts have been internationally acclaimed for their fine depictions of the region’s life and heritage.

This exciting book sweeps the reader into the world of Bob Timberlake, a world captured in rich detailed pictures by photographer Walter Pfeiffer and evocative, insightful essays by North Carolina writer Eddie Nickens The lively interplay of words and photographs is enhanced by many of Timberlake’s well-known paintings as well as a number reproduced here for the first time. Buy Now