I will always cherish the days spent along this historic stretch of the south-Georgia coast, where the currents of friendship forever run deep.

I was tired. Very tired.

Pleasingly, pleasantly tired after another long and gratifying day following the pointers and setters as we hunted bobwhite quail.

It was the kind of tired you have to earn, the kind you get only by hunting long and hunting hard and shooting as well as you possibly can. The kind of tired you are willing to travel great distances and spend great sums to be.

Dinner with my friends that evening had been yet another five course confection, and by the time I crossed the grounds to my lodge and had a long hot shower, the seventh game of the World Series was in the bottom of the fifth.

So I slipped into my pajama bottoms and a clean tee shirt, wrapped my old Indian blanket loosely around my shoulders and sank barefoot into the plush leather sofa, figuring I would surely fall asleep before it was all over.

But to the contrary, it was a lively, compelling final few innings, well-played and seasoned with plenty of drama and suspense, and by the time the game was finished it was after midnight and I was wide awake. I knew it would be pointless to try to get to sleep, so I stepped outside into the cool October air to take in the stars and feel the crisp, salty night wind and listen to the whisper of the Atlantic running south with the rising tide.

Peering east across the broad channel, I could see a few scattered lights ghosting in the darkness there on Cumberland Island, and a hundred yards through the pines loomed the sprawling dock.

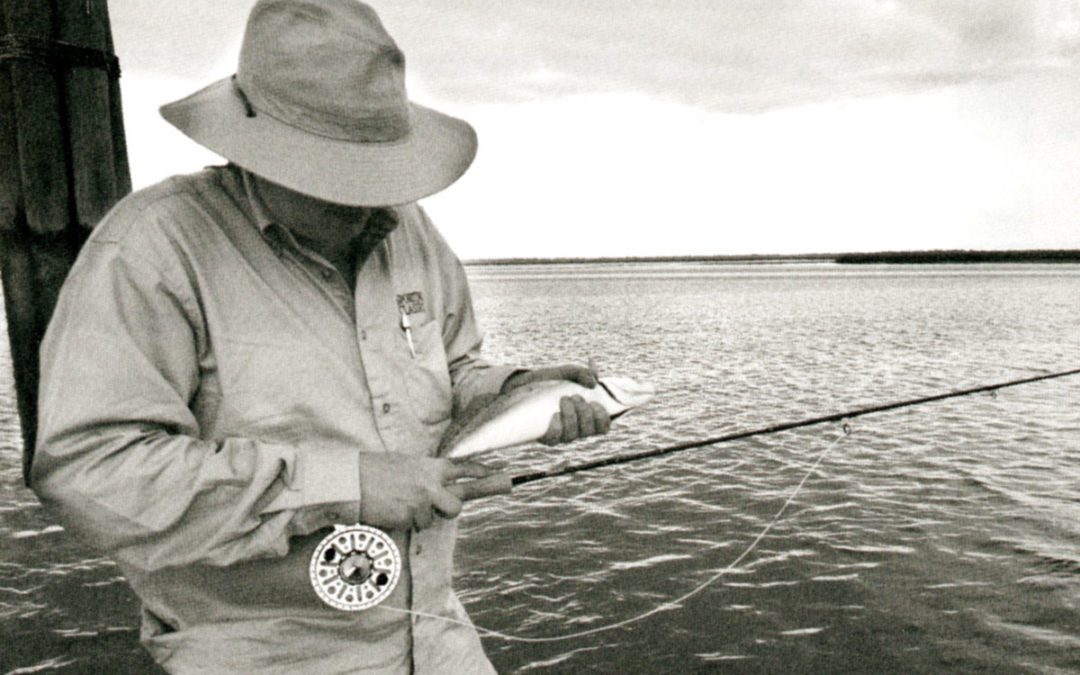

So I stepped back inside to fetch my fly rod from the corner where I’d left it 13 hours earlier following the lunchtime break I had taken with Kimberly to that same dock, then eased barefoot and alone through the dew-laden grass to the sea.

I still don’t know why I took my fly rod . . . habit I suppose. But once out over the water, I was happy to have it, for the tide was nearing high, and in the chiaroscuro light from beneath the dock I could see the undulating schools of menhaden running strong with their faces into the south-flowing current.

I had just begun to wonder what might be lurking below them when suddenly there was a flash, then another beneath the murky surface as some creature higher in the food web tore through the baitfish. Quickly I began stripping line from the reel and sent my chartreuse-and-white Clouser out to survey the depths. But the fly barely had time to sink a few inches before something significant tried to take it from me.

It was an oversize sea trout, at least 24 inches long, much larger than the ones I had caught earlier that day as low tide had shifted from south to north. This fish dove deep and away, and the fly line flew from my reel as its song rang sweet and clear through the crisp salt air and out into the night. For a moment I nearly lost her as she dove for the barnacle-encrusted pilings. But the drag on my fly reel was smooth and sure, and four minutes later I lifted the big trout from the current.

For the next three hours it was as though the night had paused around me as I probed the edges of the darkness with fly and line, shuffling barefoot up and down the rough wood-and-concrete decking until my feet began to bleed, catching fish after fish as the high cloud cover grew to obliterate the stars.

But the trout continued hitting and I continued catching them, pausing occasionally to re-sharpen my single barbless hook on the exposed concrete pilings, time after time slipping it from the fishes’ mouths and returning them whole and alive to the sea. It was a timeless interlude of nearly unbearable bliss, fishing there alone with the only illumination coming from the stars and the dimming lights across the channel and, of course, those close beneath the dock.

I could have fished all night, and in fact I nearly did. But with the temperature steadily falling and the shifting north wind boring inexorably through my thin attire, I finally slipped the point of the now-tattered Clouser into the hook-keeper in the base of my reel and slogged shoeless back through the damp, soothing grass to my lodge, where I toweled off my lower legs and cold wet feet, patched them up, slipped into some warm wool socks and drifted off to sleep for what little was left of the night.

I was at Cabin Bluff in the extreme southeastern comer of Georgia, just a few miles north of the Florida border, along with my friends Kimberly Juday and Chuck Wechsler. But we really had not come here to fish, but were instead hunting quail and deer and wild hogs.

Chuck is an inveterate hog hunter and could hardly wait to get out into the rich palmetto-laced habitat and dark woodlands and make an impression on the resident population, and before I’d even had a chance to unpack on the afternoon of my arrival, he was already in his stand.

The following morning kicked off clear and sunny, and with a cold front moving in from the northwest, the quail hunting was simply spectacular.

Once more Chuck headed out hog hunting late in the afternoon and managed to stumble into a bevy of perfectly proportioned, barbeque-size porkers, returning that night with three of them and very pleased with himself.

The next day dawned clear and cool, and again we were out for quail with guides Chuck Dean and Tommy Roberts and as fine a team of pointers, setters and Labrador retrievers as you are ever likely to find. The lush palmetto ground-cover was punctuated with swaths of coastal bluestem and clumps of blackroot and gallberry bushes that assured the quail plenty of cover and food.

Our old setter Dallas found the first covey within minutes, dutifully backed by Bandit, his young pointer protege. And when our black lab Angel was sent in for the flush, the ground erupted with quail.

I shot too quickly and missed my first bird, but then swung on a second one going away and dropped him cleanly. Meanwhile as Kimberly backed us with her cameras, Chuck calmly doubled, and our day was off to a rousing start. For the rest of the morning and well into the afternoon we alternated dogs and gunners and cameras until it was time for brother Wechsler to head back to the lodge and get ready for his evening hog hunt.

The following few days had been as good as the first, and we reveled in the luxury of this historic setting as Chuck continued to put a major dent in south Georgia’s feral pig population. But Kimberly and I continued hunting birds, until the time came for Chuck to head home.

The next morning Kimberly and I had shared one last outing together for quail and then dinner before she, too, had to leave. And so I’d wandered alone back to my lodge, watched the final few innings of the World Series, then found myself fly fishing through the night and looking forward to morning and my final hunt for bobwhites, this time with my good friend Ken Seeger who had just arrived from his home in Charleston.

Ken and I met for breakfast at 7:45, and by 9:00 we were boots- on-the-ground with our guide Wes Schlosser and another team of fine bird dogs.

Our first point came next to a tall, stately longleaf pine, and I handed my open-and-empty gun to Wes and eased into position behind Ken with my cameras, hoping to photograph the flush. Three birds burst from a thicket of gallberry as a fourth rocketed back past my left ear, and Ken tumbled two of them with his little side-by-side Churchill.

This was a truly exquisite gun, an Imperial XXV sidelock that had been manufactured in 1952 as a true 12 bore with 2-inch chambers. It sported 25-inch barrels, was choked Skeet II and IC and weighed in at a perfectly proportioned five and a half pounds.

Ken had purchased the gun from Elderkin and Son, Ltd. in England four years earlier and then had it restored by Atkin, Grant and Lang, who replaced and lengthened the buttstock and reblacked the barrels and furniture. The gun fit him like a glove, and with the 2-inch shells he purchases by the case, it produced a wonderfully uniform pattern and very short shot string, making it one of the most effective bird guns I have ever seen.

It was an elegant piece, the type of gun that makes a splendid day afield even more fulfilling, especially when you are hunting classic quail cover with such excellent companions and finely tuned bird dogs. And these dogs were truly superb.

Their fire and passion was a thing of infinite beauty and spoke volumes about the care and love and patience that had gone into their training and development. Wes hardly ever had to speak to them, and when he did, it was with a soft, kind, caring tone.

By now I had handed the cameras back to Wes and reclaimed my own gun as the dogs continued sweeping the cover. They soon locked up on their second point, and as Ken and I flanked them, Wes sent Tim, his yellow Lab, in for the flush. A bob’ and hen blew out on Ken’s side, and again the sweet voice of the little Churchill reverberated through the cool morning air as another double fell.

In seconds Tim and Bandit were back at Wes’ side with the birds, and a hundred yards farther on we found Bandit frozen solid on another point. This time it was a full covey, at least eight or nine birds tearing straight away from us. Ken and I each managed a bird apiece and then briefly followed up the singles.

We could clearly hear them as they scurried through the cover around us, anxiously calling to one another in an urgent attempt to regroup. So we backed off and left them to go about their business in peace, confident there would be more birds.

True to form, within ten minutes Bandit found yet another covey. This time they flushed wild before we were in position. But we still managed to drop two birds on the rise and then took two more on the follow-up as we delighted in the moment and the fine fellowship that is always so much a part of classic southern quail hunting.

The day was sublime and so was the setting, and the dogs and birds all performed to perfection.

Eventually we circled back to the hunting vehicle and moved a half mile to the west, where Ken and I swapped weapons. Our two guns seemed to be very closely matched in their balance and measurements, and Ken promptly doubled with my Purdey as I took three consecutive singles with his Churchill.

Laughter and good cheer filled the air as the dogs continued pointing covey after covey. We never stayed in one location for long, for there was an abundance of birds and thousands of acres in which to hunt them.

By day’s end we were tired and content and ready for dinner, and I slept well that night with the steady whisper of the sea drifting in through my open bedroom window. Ken and I met for brunch the next morning at 10:00, and it was well past noon before I hit the road.

I’ll be back in the spring for redfish and trout. And most likely, I will return for deer and quail come fall.

But one thing is certain – I will always cherish the days spent along this historic stretch of the south-Georgia coast, where the currents of friendship forever run deep.

This is one of over 40 beautifully written short stories you’ll find in Michael Altizer’s Nineteen Years to Sunrise. Buy Now

This is one of over 40 beautifully written short stories you’ll find in Michael Altizer’s Nineteen Years to Sunrise. Buy Now