“He who hesitates is lost,” the old saying goes. I hesitated and my guide and I were almost lost for good. Had I pulled the trigger two seconds sooner, there would have been no problem. We could have skinned out a fine trophy goat in warm sunlight and had a pleasant stroll down the mountain. But that two-second delay pretty much ruined my day.

It was the best day of the season for hunting goat in British Columbia. The mountain air, kissed by frost then warmed in morning sun, was like a clear, dry wine. Birch trees, shedding their cares for the winter, showered the earth and waters with shimmering gardens of golden doubloons. The horses stamped and snorted jets of steaming air, eager to go to the mountain, and when I climbed into the saddle, the pancakes and bacon felt just right in my belly. It would be a good ride, eight or ten miles to the mountain beyond the mountain where the big goats were.

I was hunting out of Coyne Callison’s main camp on the Turnagain River in one of the best big-game areas in North America. Within easy walking distance of Callison’s comfortable log cabins are plenty of stone sheep, moose, goats, black bear, and grizzlies. Every season Callison’s hunters return with trophies that qualify for the Boone & Crockett record book. I expect there just might be a world record Canada moose loafing around there somewhere. In 1983 one of Callison’s clients took the number two moose. I saw three big grizzlies in two days and lost count of the moose.

My hunting pals were outfitter Jack Atcheson and Bob Funk, a boy wonder of the oil industry. Atcheson books most of my big game hunts, and we’ve come to be known as the Golden Boys because of our incredible luck when we hunt together.

After arriving in Callison’s camp via floatplane from Watson Lake in the Yukon, we’d split up, with Jack and Bob going to separate spike camps for moose and sheep. I was after a big billy goat, but I also had tags for moose and grizzly.

To my notion, the North American mountain goat is one of the world’s most underrated game animals. Not underrated perhaps so much as ignored. One has only to look at the places where goats live to decide there are easier things to hunt. Yet a big billy is one of the most magnificent trophies in North America. He is a solitary creature of the high and wild places, a determined and resourceful survivor. A beautiful but stinking and conniving con artist that borrowed his face from the devil and his feet from angels. He survives not by killing his enemies but by luring them to places there they kill themselves. His siren call is the wind and his weapon the mountain.

My guide was Claude Smarch, a savvy young fellow who learned the business from his father. Claude had been after a particularly big billy all season, but hadn’t been able to get a hunter within range. The goat had a lookout position near the peak of his mountain fortress that gave him a view of most access routes. That made him all but impossible to stalk because when he spotted hunters coming up the mountain, he’d sneak off by way of his secret escape route.

But like I said, it was the best day of the season to hunt goats and I was feeling lucky. A feeling that blossomed when Claude and I arrived at the foot of the mountain and hid our horses in a willow thicket. Far above us, the old billy was resting in his favorite lookout spot, though he hadn’t noticed our arrival because we’d sneaked in through a back door of our own. If he stayed put for the next few hours, we had a chance of climbing the mountain undetected and pulling off a stalk.

The mountain was steep and tall but I’ve been on worse. Anyway, a mountain is always easier to climb when there is game waiting at the top. A few weeks earlier, while making a movie for Remington Arms, I’d buggered my knee so that walking was a bit painful, especially when angling around hillsides. For this reason I found it less painful to climb straight up rather than following the usual switchback climbing technique. The result was that even with a bum leg I’ve never climbed faster. By midmorning we were near the peak and had begun creeping around to where we’d last seen the goat.

Everything seemed too perfect and it almost was. We calculated that we were about 50 to 70 yards above the goat’s lookout spot, which was a narrow bench. By simply circling around the mountaintop and not making any serious mistakes, such as causing a rockslide, we hoped to put ourselves almost on top of the wary old billy before he got wise to what was happening.

But something always seems to go wrong when the setup is too perfect. The old goat wasn’t where he was supposed to be. That meant he’d either hightailed it over the crest while we were on the blind side of the mountain, or had simply moved one way or another along the bench. From our position we could only see a few yards ahead, so after a whispered planning session, Claude and I separated, each working our way around the mountain and keeping our eyes on the narrow bench-like ledge.

We’d been separated only a few minutes when I heard a small pebble land at my heels and turned to see Claude motioning for me to head back. He’d spotted the billy, he lip-whispered, lying behind a boulder at the narrowest part of the bench. To get a clear shot I’d have to cross a steep shale face. I’d be in easy view of the goat if he looked up, and if I kicked loose a single stone, it would surely spook him. Already we were within 70 yards of the billy and had to move like ghosts.

Despite the short range, I wouldn’t get a clear shot until I was even closer because of the convex curvature of the open shale face. As I worked my way toward the billy, planning each step with breathless care, I could see his horns and head but nothing more. Finally though, after spending 10 minutes crossing less than 20 yards, I settled into a sitting position behind a rock outcropping. Now the goat was too close to miss. How could anything go wrong?

Pinching the rifle’s safety lever between my fingers so it wouldn’t make a sound, I steadied the crosshairs on the goat’s backbone. At this downhill angle, steeper than 45 degrees, the 250-grain Nosler bullet from my .338 Winchester Magnum would sever the backbone and drive on into the lungs and heart.

All I had to do was press the trigger, but I hesitated because the goat was lying down.

Once I had a foolproof shot at a resting antelope and missed him clean. I never did figure out how I missed, unless I was fooled by the angles. An animal in its bed can be a deceptive target and, besides, I just don’t like to shoot them that way. So I waited. Soon the goat would be on its feet and I’d have a fair shot.

Claude, I knew, wanted me to kill the goat in its bed, and for good reason. If it moved a few steps either way it would be out of sight. Worst of all, if it went over the edge of the bench it would fall more than a thousand feet into a deep ravine. Many trophy goats have been badly damaged by such falls, some lost and never found. But still I held my fire because when an animal gets up, even if it’s spooked, it will usually stand still for a moment, determining the source of danger before deciding which way to run. In times past I’ve spooked deer and elk and other game out of their beds and had ample time to get off a shot while they were deciding what to do.

Already the goat sensed something was wrong and would soon be up. He was moving his head in quick jerks, trying to see everywhere. This gave me a good look at his horns, shining black and hooked at the tips like Arab daggers. If the horns of a Rocky Mountain goat measure nine inches or more he is a really good one. I estimated the old billy’s horns at about 9½ inches and was having visions of his head on my trophy room wall when suddenly he looked straight at me. He was running even before he was fully on his feet—toward the edge of the cliff!

My bullet caught him just as he dived over the edge and tumbled into space. He was dead in the air, no question about that. Claude and I both saw a bright red spot high on his shoulder.

When I climbed down to the bench and looked over the edge, I could only hope that the goat hadn’t fallen far and had been stopped by a tree snag or boulder. But no such luck. As far down as we could see there was nothing. My goat was somewhere far below in a deep ravine, and now we’d have to go find him.

“Okay, Claude,” I said, trying to sound optimistic, “This is what you’re getting paid for . . . let’s go get him.”

“It’s a long way down there,” he answered trying to match my optimism with a half-hearted grin, “But one thing’s for sure, when we find him he’ll be half-skinned.”

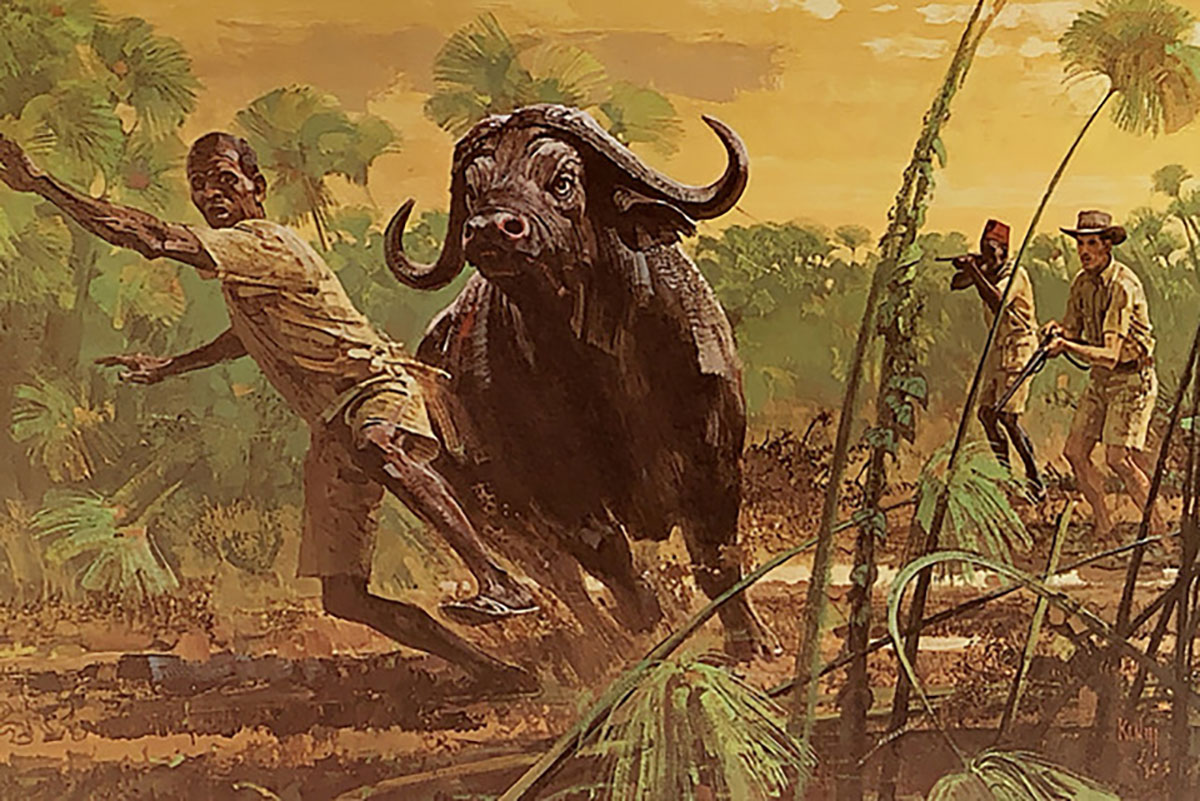

Struck by Carmichel’s bullet in mid-air, the billy plummeted into this deep ravine where the author and his guide risked their lives struggling to carry out the head and hide.

It was a long way down, but that didn’t worry me half as much as the fact that it was also a long way back up. As far as I could see there was no way out of the black ravine, except to climb out. The morning’s hike up the mountain would be a cakewalk compared to what lay ahead.

While Claude took a more or less direct route, sliding and falling on the loose shale, I followed a slower course, looking for a way to come back up the mountain. In places the steep mountainside gave way to vertical rock walls, and I’d have to make long detours, stopping often to look back, making certain that I could find a climbable route out.

Though the day had been pleasantly warm, it was cold and dark in the ravine with great sheets of ice clinging to the rock walls. Apparently the sun never penetrated this lonely place.

“Over here,” Claude shouted from my right, “He’s wedged behind a rock.”

“Can you climb back up from where you are?” I shouted back.

“No way, it’s too steep here. I’ll have to keep going down and hope for the best.”

“Wait until I get below you, then roll the goat on down.” Not far below us a torrent of water surged through the ravine. I wanted to be where I could grab the goat before it was swept away by the current and lost forever.

With each step down, the ravine became colder and darker while far above, the crest of the mountain gleamed in the sunlight. The streambed was a jumble of boulders, torturing the water into a roaring cataract. Finding a place where I had fairly good footing, I shouted for Claude to let the goat slide down.

Moments later there was a crashing from above, a shower of loose dirt and rock splattered around me, and the goat splashed into the water. It would have been swept away in an instant, but I managed to grab a handful of hair and hung on, pulling it onto a flat rock.

While Claude caped the animal, I backtracked up the mountain a short distance, wanting to make sure we had a way out. I’d briefly considered following the stream out of the ravine but abandoned the idea. Every few yards the water plunged over a precipice and fell several feet. What falls I could see could be negotiated without trouble, but it was the falls I couldn’t see that bothered me. What if we got into a place where it was too steep to go down and too high or slippery to go back up? It would be a bad way to be stranded. A misstep on an icy rock could mean a broken leg, and then what?

“What are you doing up there?” Claude yelled when I was 50 yards above him, hunting my original trail.

“We’ve got to go back up this way,” I answered, “because we might get trapped in the ravine if we follow the stream.”

“Don’t worry,” he answered, surprised at my concern, “this way we’ll be out in an hour. If we climb back the way we came, we won’t be back to camp before dark. Besides, it’s safer this way than trying to climb up that loose rock.”

“Okay,” I said, resigning myself to an uncertain fate, “you’re the guide, so start guiding us out of here.”

The first few waterfalls were no more than five or six feet high, and could be climbed if we had to backtrack. But as we went farther downstream, the sheer ravine walls squeezed together and the falls became progressively higher. That’s when we came to the place I had been dreading. I heard it even before I saw it, the water crashing down for 10 feet, then exploding into spray that froze on the ravine walls.

“Claude, if we go down there, we won’t be able to climb back up.”

“Don’t worry, we won’t want to come back this way anyhow, we’ll soon be out.”

Claude went first, hanging onto my hand, then falling about five feet to the rocky streambed.

“Com’on,” he urged, “It’s not bad at all.”

I tossed our backpacks down, then the goat’s head and hide, and lastly, my prized David Miller custom rifle.

Rolling over on my belly and sliding off the rock shelf at the side of the falls, I inched down until my feet touched Claude’s shoulder and then I was safe.

“See,” Claude said, “nothing to it.”

I was nearly convinced until we rounded a sharp bend and peered over the edge of the next waterfall. It was over 20 feet to the bottom, and there was no possible way to climb around. The rock walls on both sides were straight up and down and covered with ice. There was no way out but down and that meant a long jump. It also meant we’d land in the water below. But how deep was it? Deep enough to cushion our fall or did the foaming water hide solid rock?

Clearly, there was no reasonable choice; to jump into the unknown water was too much of a risk. The shock of the freezing water would be bad enough, but hitting a hidden rock would be even worse. The chances of surviving the fall without serious injury, I calculated, were perhaps one in three. Not very good odds. If both of us were injured or knocked unconscious, our chances of survival were next to nothing. Who would look for us in that dark ravine?

Our only hope was to go back upstream and try to climb out at the last falls. But would it be possible? For a long while we tried to get a hand or foothold on the slick rock but it was no use. Just as I had feared, there was no way to climb out. We were trapped.

Claude and I knew we were in one hell of a fix, but we never admitted it.

“Let’s take a break,” I suggested, “No use burning up our energy. After we’ve rested we’ll figure this out.”

Mentally, I went over the equipment I carried in my daypack. There was about five feet of nylon cord strong enough to hold a man’s weight. What else? I wondered. My rifle sling, that’s four more feet! Can we tie enough sling and cord and strips of clothes together to let ourselves down? Sure! We’d make it out of this hell-hole after all. A bit wet and cold but at least in one piece.

While I was putting my ideas together, Claude was doing some thinking on his own. “If that tree were a few feet longer we could use it like a ladder,” he said, pointing to a bleached length of spruce wedged between some boulders.

“It’s long enough!” I shouted. “Let’s get it loose and drop it alongside the falls.”

“But it’s too short,” Claude protested, “Not more than ten feet. Even with the log leaned up on the ravine wall, we still have over ten feet to fall.”

“We’ll tie my rifle sling to some cord I have and loop it around a rock at the top. Then we can let ourselves down to the log and shinny down the rest of the way.”

After tying the cord to the leather sling, we looped it around the stub of a limb at one end of the spruce log and swung it into position. This was accomplished by lying on the edge of the waterfall, half in the current, and stretching my arms until they ached. Claude held onto my legs to keep me from being washed over the edge. After a couple of tries, and almost dropping the log, I got it leaning against the wall at an angle that I hoped would hold. Next we tied a loop around a rock at the edge of the shelf. This left about five feet of cord and sling to hold onto, with another five or six feet to the top of the nearly vertical log.

Claude went first, wriggling off the edge of the rock shelf and letting himself down slowly. When his boots found a hold on the log, he waited a moment to catch his breath, then let go of the sling. For a moment he seemed to teeter in mid-air, then ever so carefully he bent his knees until he could grab the top of the log in his hands. Then he easily slid down the thin log and was safely on solid rock.

Next I tossed the packs and hide down and—holding my breath—let the rifle fall. Claude caught it and I raised my eyes to heaven in thanks

“Your turn Jim. It’s as easy as rolling off a log.”

“That’s not funny,” I answered.

The tough leather sling felt strong in my grip as I inched off the shelf and let myself slide down the icy rock. I didn’t look down or up, only at my bare hands gripping the leather. “How close am I?”

“Just a few more inches, keep coming.”

Then my boot touched the log and it felt good to shift my weight to my legs. After that it was like climbing down a ladder and I was beside Claude, looking up at the sheer wall of ice-covered rocks. It seemed impossible.

“That’s a good sling up there, Claude,” I said, “If you ever come by this way again, be sure and get it for me.”

“If you don’t mind,” he answered, “I’ll just buy you a new one.”

I guess that rifle sling is still there, dangling from a short length of nylon cord in a deep, dark ravine that the sun has never discovered.